- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Russia saber rattling gets the West talking. Is a deal with NATO next?

- Party of one: Why record numbers of Americans are going it alone

- Room for everyone: Tribal college expands its reach

- Low-level traffic stops decrease; Saudi women in the workplace increase

- To clean up East Baltimore, this mentor shores up buildings – and youths

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

For young digital nomads, the lures get more global

Ever think about pulling up stakes and setting up somewhere new?

There has long been a small, robust community of new retirees considering life abroad in relaxed countries with cheap health care. Today it’s not just expat pensioners feeling footloose. As a young Monitor writer remarked recently in a meeting, some in his cohort see the unmatched “land of opportunity” label on the United States as fading.

While voluntary migration is sometimes oversold – and, for many, unaffordable – mobility seems more real. A recent national survey of some 6,000 U.S. workers had 78% indicating a desire to keep the option to work remotely for good. They point to pandemic-era evidence that knowledge work can be done well at a distance. Workers have leverage.

If they’re feeling a little ambivalent about American opportunity, younger workers are also willing to rethink success and where to find it. First came a turning away from urban centers. Digital nomadism showed up in the forms of van-lifers and people lighting out for rural Zoomtowns. Vermont offers a relocation grant program. So do Tulsa, Oklahoma; Topeka, Kansas; and other U.S. cities and regions.

Next, perhaps: a broader definition of home. As travel eases, borders blur, and not only for American prospectors. The knowledge-worker traffic is omnidirectional. Estonia welcomes innovators to its old world but highly digital hubs. Some European countries are seeking a return of top talent that had left.

Now Buenos Aires is touting Argentina’s weak currency to appeal to foreigners’ buying power – and offering a special 12-month visa to remote workers with income from abroad. The aim, according to Bloomberg City Lab: Attract 22,000 nomads by 2023.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Russia saber rattling gets the West talking. Is a deal with NATO next?

By building up troops near Ukraine, the Kremlin has been pressuring the West to talk about NATO expansion. Amid diplomacy, Moscow feels like it might be heard. We look at its aims.

No one in Moscow seems able to explain why Vladimir Putin has chosen the current moment to issue an ultimatum over NATO’s oft-restated intention to eventually bring Ukraine into the alliance.

But most analysts agree that the Kremlin initiated suspicious troop movements along the Ukrainian border late last month to force that conversation to happen. And it seems to be starting to do so.

During their video summit last week, President Joe Biden appears to have told Mr. Putin that talks could take place around Russian demands in order to see whether “we can work out any accommodation as it relates to bringing down the eastern front.” Mr. Putin said that a document outlining the Russian position would be sent to Washington very soon.

In a subsequent phone call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Mr. Biden pressed the Ukrainian leader on the need to implement the Minsk-2 peace deal, which requires direct talks with the two Russian-backed rebel republics in eastern Ukraine.

Mr. Putin has “drawn a line,” says Alexander Baunov of the Carnegie Moscow Center. “Russia will never agree to the prospect of a Ukraine in NATO, or any U.S. military base there, or even the future possibility of millions of Russian-speaking Ukrainians being Ukrainianized.”

Russia saber rattling gets the West talking. Is a deal with NATO next?

NATO’s ongoing expansion into Eastern Europe and former Soviet lands has been a bitter issue for Moscow for almost 30 years.

The Kremlin has watched all the former Soviet Union’s Warsaw Pact allies and three former Soviet republics join NATO, while the front line between NATO and Russia has moved about 600 miles to the east. The Russians claim, with considerable evidence, that former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was given strong verbal assurances that NATO would move “not one inch” eastward.

Now, Vladimir Putin seems to believe that it’s finally time to get that in writing.

No one in Moscow seems able to explain why Mr. Putin has chosen the current moment to issue an ultimatum over NATO’s oft-restated intention to eventually bring Ukraine into the alliance. But most analysts agree that the Kremlin initiated suspicious troop movements along the Ukrainian border, in Russia’s Western Military District, late last month in order to force exactly that conversation to happen.

Few believe that Russia actually intends to invade Ukraine – a war that would be intensely unpopular at home. Nevertheless, the Kremlin keeps reiterating that military options are on the table if its concerns aren’t satisfactorily addressed.

“What Russia wants is a dialogue with leading NATO powers that would move the discussion away from the standard Western view that Europe’s security order is fine but just has a Russia problem, to an examination of the dangerous flaws in Europe’s security system and the need to address Russia’s concerns,” says Fyodor Lukyanov, editor of Russia in Global Affairs, a leading Moscow-based foreign policy journal. “It is not yet clear whether that is going to happen in any acceptable form or not. So the crisis continues.”

Russia’s red lines

The White House readout on last week’s video summit between Mr. Putin and President Joe Biden insists that Mr. Putin was sternly warned of serious consequences for any attack on Ukraine, including devastating sanctions and “other measures,” presumably supplies of arms and support to Kyiv.

The Kremlin version acknowledged that, but added Russian grievances over the growing penetration of NATO into Ukraine and Kyiv’s foot-dragging on implementing the Minsk-2 peace deal, which requires direct talks with the two Russian-backed rebel republics in eastern Ukraine.

Mr. Biden appears to have told Mr. Putin that talks could take place around Russian demands in order to see whether “we can work out any accommodation as it relates to bringing down the eastern front,” perhaps involving a few top NATO allies, while Mr. Putin said that a document outlining the Russian position going into those talks would be sent to Washington very soon.

In a subsequent phone call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Mr. Biden offered strong support for Ukraine and insisted that Russia would have no say in its bid to join NATO, but also pressed the Ukrainian leader on the need to implement the Minsk peace deal.

Amid all this ambiguity, Russia appears to have received the message that the United States may be prepared to offer some concessions, if not outright guarantees about future NATO enlargement.

“The way things stand right now is that Biden gave no promises concerning Ukraine’s membership in NATO, and Putin did not clarify anything about Russia’s intentions toward Ukraine,” says Vladimir Yevseyev, a security expert at the official Institute of World Economy and International Relations in Moscow. “Russia has three red lines about Ukraine: no NATO membership, no U.S. military bases on Ukrainian soil, and no offensive armaments stationed near Russia’s borders.”

Experts suggest that the Kremlin’s vision is to create a system of neutral states between NATO and Russia, perhaps something like Finland or Austria during the Cold War – no one uses the sensitive word “Finlandization,” but that seems close to what they mean. The system would be secured by international agreement, with guarantees for the independence, sovereignty, and democratic choice of those former Soviet countries, especially Ukraine and Georgia.

Chances of the U.S. and its allies accepting that idea seem vanishingly slim, say experts. Even Mr. Biden’s offer to hold talks with Russia and a few key NATO allies has run into a firestorm of objections from Eastern European allies who oppose any dialogue with Russia.

“For Russia, everything depends on whether Biden is serious about getting a group of leading NATO allies together to discuss specific concerns Russia has about NATO,” says Andrei Kortunov, head of the Russian International Affairs Council, which is affiliated with the Foreign Ministry. “It’s an important gesture Biden made, and any positive development will be appreciated by the Kremlin.”

Balancing tensions

Short of a grand bargain about NATO enlargement, trust-building deals could be cut about positioning of weapons in Eastern Europe, limiting of missile defense systems in Europe, and other stabilizing measures that might mollify the Kremlin.

“Biden needs to balance his support for Ukraine with his desire for better relations with Russia,” says Mr. Kortunov. “All the talk in Washington these days is about concentrating on the Chinese threat, but that will be much harder if tensions are spiking with Russia in the West.”

Mr. Biden’s pledge that he would nudge Ukraine to implement the Minsk-2 accords presents another political minefield. The agreements, signed at a moment of Ukrainian weakness in 2015, require Kyiv to talk directly to rebel leaders and would reintegrate the Russian-speaking regions in Ukraine’s Donbass back into the whole, but with permanent autonomy. That’s political poison for Ukrainian nationalists, who foresee building a unitary Ukrainian state from the complicated territorial patchwork that Ukraine inherited from the Soviet Union.

“Zelenskyy can move to implement the accords, as Biden suggests, but once he begins he will face a serious political crisis,” says Vadim Karasyov, director of the independent Institute of Global Strategies in Kyiv. “People will say he caved in to American pressure, and his chances of getting reelected will diminish. It’s an unfortunate paradox, but the less tension there is between the West and Russia, the greater are the chances for internal discord in Ukraine.”

The consensus of analysts is that the crisis may be in abeyance for the moment, but is far from over.

“Vladimir Putin is totally unwilling to accept the old status quo anymore,” says Alexander Baunov, an expert with the Carnegie Moscow Center. “He’s drawn a line. Russia will never agree to the prospect of a Ukraine in NATO, or any U.S. military base there, or even the future possibility of millions of Russian-speaking Ukrainians being Ukrainianized. It’s not clear what he plans to do if there is no constructive communication with big Western powers – which is what he wants – but he is definitely not going to let it go.”

A deeper look

Party of one: Why record numbers of Americans are going it alone

As with work arrangements, so too with relationships. For a growing number of dedicated singles, the tightly defined historical norm has become much more an option than a default.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 12 Min. )

Brigette Eaton felt for a long time that she didn’t have many options outside her community’s expectation that she should marry and start a family.

Raised in the traditions of Black Protestantism, Ms. Eaton says she married in 2011 mostly out of religious obligation.

“I mean, I really love my ex-husband. We were good friends,” says Ms. Eaton, who divorced in 2014 and is pursuing a Ph.D. “It’s just that we wanted totally different things in life. It just didn’t feel right, you know.”

More Americans are finding that they may just prefer living alone – even if they also feel the weight of a society whose social rituals and legal structures have been built around families.

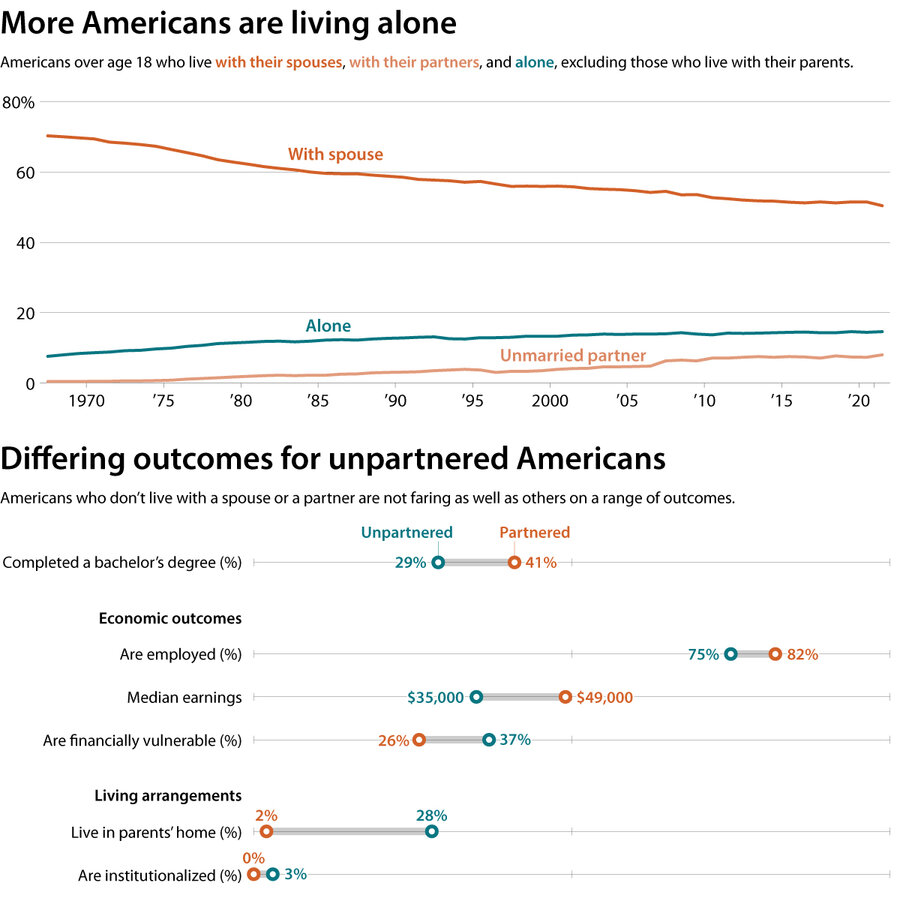

In 2020, nearly 4 out of 10 adults between ages 25 and 54 were neither married nor living with a partner – a 30% increase since 1990, according to a Pew Research Center study. The number of single-person households in the U.S. has doubled from 18.2 million in 1980 to 36.1 million today, according to census figures.

“There are few truly revolutionary transformations in the way that we live as human beings, and this is one of them,” says Eric Klinenberg, author of “Going Solo.” “It’s ‘extraordinary’ because in the history of our species until the middle of the 20th century, there was never a society that sustained large numbers of people living alone for long periods of time.”

Party of one: Why record numbers of Americans are going it alone

When Hilary Reiter left New York City 20 years ago and moved to Park City, Utah, she didn’t think she would still be single two decades after moving out West.

Even as the number of single adults across the country continues to reach unprecedented levels, Ms. Reiter says she never made a “proactive decision” to forgo marriage and live alone. In some ways, she’s remained unattached into her 40s due to happenstance.

“But I also think there’s more to it than that,” says Ms. Reiter, who has never lived with a romantic partner. “I was never one of those girls who wanted the 300-person wedding and white wedding dress. I am staunchly independent, and maybe one of my weaknesses is my inability to compromise. I like having my own space; I like being able to come and go as I please and not have to accommodate somebody else.”

“I guess I also like not having any drama,” she says. “I feel like so many of my relationships were just dramatic and full of heartbreak. Some of them were pretty toxic.”

The number of single adults in the U.S. has been rising steadily since the 1950s, researchers say, when about 1 out of 4 adults were unmarried – and many were single men who migrated west to work in places like Alaska. Back then, as for most of human history, there remained a deep-seated social expectation that after coming of age, most full-functioning adults would find a vocation, get married, and start a family.

Today, however, nearly half the adult population is single – about 128 million Americans. This demographically diverse and socially mixed group includes people at different stages of their lives, as well as single parents, LGBTQ individuals, romantic partners who cohabitate, and those simply waiting longer to find the right person.

Yet more and more people are finding that they may just prefer living solo – even if they also feel the weight of a society whose social rituals and legal traditions have been built around a world expecting couples and the families they start.

In 2020, nearly 4 out of 10 adults between ages 25 and 54 were neither married nor living with a partner – a 30% increase since 1990, according to a recent Pew Research Center study. More significantly, the number of single-person households in the U.S. has doubled from 18.2 million in 1980 to 36.1 million today, or about 28% of the nation’s total, according to census figures. An additional 11 million homes are headed by a single parent, triple the number in 1965.

Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 1967-2021; Pew Research Center

“There are few truly revolutionary transformations in the way that we live as human beings, and this is one of them,” says Eric Klinenberg, a noted social thinker at New York University and the author of “Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone.”

“It’s ‘extraordinary’ because in the history of our species until the middle of the 20th century, there was never a society that sustained large numbers of people living alone for long periods of time,” he says.

When she was in her 20s Ms. Reiter was living in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, working in the music industry and just beginning her career in public relations. After 9/11, however, she had an opportunity to work three months for the Sundance Film Festival.

“I figured, OK, I’ll go to Utah for three months, I’ll experience the glitter of Sundance, I’ll ski my heart out, and then I’ll go back,” Ms. Reiter says. “But then I never went back. The quality of life here was just too good.”

Although there were far more single men than women in Park City, most were involved in the city’s ski and tourism industry, she says, and few attracted her in a deep way.

She found that living alone simply suits her – even if she hasn’t ruled out the possibility of meeting someone, someday. Still, one of the biggest drawbacks, she says, is the not-so-subtle social stigma surrounding being single at her age, especially since she’s a woman.

“Sometimes you don’t get invited to certain gatherings because you don’t have a significant other, and I think people feel – I don’t know, they ask questions like, ‘Are you dating anyone?’ And if you’re not, ‘Why aren’t you dating anybody?’” says Ms. Reiter, who in 2010 launched her own marketing and public relations firm in Park City.

“Now I kind of feel compelled to correct some of the myths out there that, you know, single people are miserable and that we’re unfulfilled in our lives,” she says. “Some of us are very satisfied being single and would kind of like to set the record straight on that.”

Dr. Klinenberg, too, expected to find groups of isolated, lonely, and depressed people when he first began to study the steady rise of single adults over two decades ago. “The general conversation about people living alone at the time was that it was an alarming sign of social atomization, or that there must be something wrong with people who lived alone,” he says.

“So I thought I was going to be writing a book about an emerging social problem,” Dr. Klinenberg continues. “Instead, what I found was that the majority of the people were actually in pretty good shape and pretty content, and that was surprising to me.”

The reasons for this transformation are in many ways rooted in the revolutionary changes of the modern world. The growing affluence of postwar Western societies made living single a viable possibility for more people, even as modern social support systems began to bolster rising household incomes. At the same time, waves of revolutions in communications technologies allowed people to connect in dramatically different ways than before.

One revolutionary transformation driven by the rise of singles, in fact, has been the revitalization of urban life. As younger Americans embraced city living, they in many ways wanted to live alone, together, Dr. Klinenberg says, and spend a lot of time and money in public spaces. Conversely, with so many public social connections, including those online, living alone affords a kind of “restorative solitude.”

“There’s many reasons for the rise of solos, but the number one reason is probably the rise of women, both economically and educationally,” says Peter McGraw, a behavioral economist at the University of Colorado Boulder. “Once women are given an alternative path to survive and thrive economically, many of them are going to opt out of the patriarchy. Suddenly getting married and having kids is an option, not the default.”

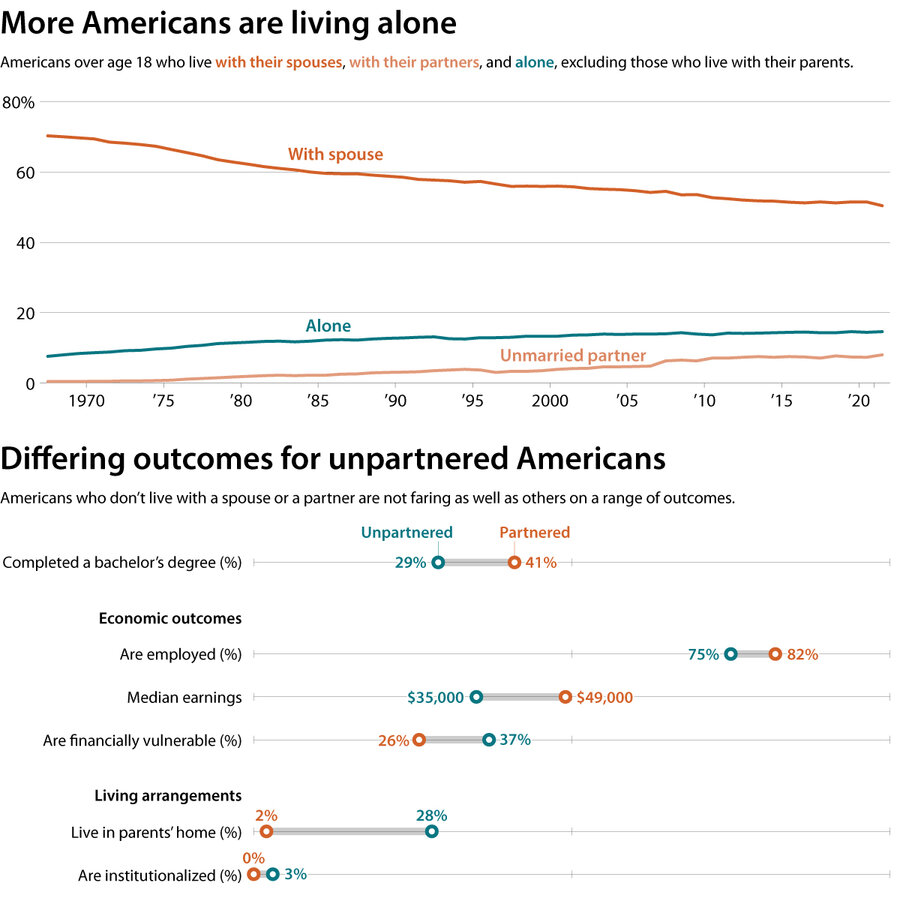

Brigette Eaton felt for a long time that she didn’t have many options outside her community’s expectation that she should marry and start a family.

Raised in the traditions of conservative Black Protestantism in Baltimore, Ms. Eaton says she married in 2011 mostly out of religious obligation. She never wanted to have children, “and I never even looked at marriage as a financially beneficial thing. I just looked at it, as you know, essentially what you do in order to not be in sin.

“I mean, I really love my ex-husband. We were good friends,” says Ms. Eaton, who divorced in 2014. “It’s just that we wanted totally different things in life. It just didn’t feel right, you know, as they say, feeling right about something in the spirit.”

She wanted to live in the city, and she is committed to her career as a crisis counselor, now in the process of getting her Ph.D. After launching her own private practice two years ago, she’s become a lot more financially independent. Since the pandemic, too, Ms. Eaton says she doesn’t feel a deep need for physical intimacy.

She’s only now starting to find a way to conceive and embrace what now feels like her natural state. As a person of deep faith, Ms. Eaton finds comfort in a passage in I Corinthians, where the Apostle Paul tells those unmarried or widowed that it is better to remain unmarried, like he is.

But she also came across the work of Dr. McGraw, who is building a community through his podcast, “Solo: The Single Person’s Guide to a Remarkable Life.”

After listening to an episode about attachment styles, Ms. Eaton had a sudden realization after she scored as an “avoidant” in relationships: “I just want to be single,” Ms. Eaton says. “And then what’s funny is, I feel, now I don’t feel alone.”

Dr. McGraw began to study the rising number of single people for deeply personal reasons, he says. A lifelong bachelor in his 50s, he says he had struggled his whole life with being single, experiencing heartbreak and broken engagements along the way.

“I thought, ‘What is wrong with me?’” he says. “You feel guilty for not wanting this thing that I’m supposed to want, and now I’m hurting this person who is being perfectly reasonable about what she wants.”

“I like dating. I like having relationships,” he says. “But I was very slow to recognize that there’s a way to be single like that with integrity.”

In his podcast, he often discusses how people can “get off the relationship escalator” and instead focus on developing deep friendships and meaningful connections, putting aside the assumption that every romantic encounter should, or could, escalate to a potentially lifelong partnership.

In one recent episode, he and his guests analyze “The Golden Girls,” discussing how single people are experimenting with housing and re-envisioning living spaces in ways beyond traditional roommates. One guest purchased a five-bedroom house and was remodeling it to include a bathroom in every room.

Social psychologist Bella DePaulo helped pioneer the study of single people with her 2007 book, “Singled Out. How Singles Are Stereotyped, Stigmatized, and Ignored, and Still Live Happily Ever After.”

There remain a number of significant structural obstacles, says Dr. DePaulo.

Much of her work has detailed what she calls “singlism,” including various employment practices, tax perks, and a host of laws and social traditions that benefit married couples.

She had already established herself as an expert in the psychology of lying and detecting lies in the mid-1990s when she started talking to some of her single colleagues about the slights they often faced, such as being asked to cover courses in time slots married faculty didn’t want, or when coupled friends “demoted” invitations to lunch instead of dinner.

“The informal slights were already bad enough,” Dr. DePaulo says. “As a single person, I was being treated as though I was not fully adult, as if my time and even my life just wasn’t as important or as valuable as married people’s. In my conversations, I found that other people were feeling the same way.”

In many ways, advocates for single people follow the same road maps as a generation of LGBTQ advocates: Why can’t good friends share the advantages of couples when it comes to health care plans, filing taxes jointly, or designating each other as beneficiaries for benefits such as Social Security?

She often cites former Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy’s controversial ode to the centrality of marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges, legalizing same-sex marriage: “Marriage responds to the universal fear that a lonely person might call out only to find no one there.”

“What Justice Kennedy said was so stigmatizing of single people and single life,” she says. And while she fully supports marriage equality, “I want single people, regardless of their gender identity or sexual orientation, to be included in the progress that is made.”

Those who are single, in fact, tend to contribute more to the civic life of their communities, Dr. DePaulo and others have found.

When Robert Trout was going through a heartbreaking if amicable divorce over a year ago, he says he was feeling both disoriented and lost, envisioning a socially isolated future as a man his age now divorced and single.

“I was devastated, to be perfectly honest,” he says. “I wanted a life with my wife and child. I wanted that dream.”

“I had all this stuff come up: Shame about failing, experiencing grief, all of it in the forefront emotionally,” says Mr. Trout, the founder of the Experiential Healing Institute in Paonia, Colorado, which helps parents navigate the needs of children with addiction or behavioral issues.

Then he found Dr. McGraw’s podcast. He was skeptical it might be just another self-help offering. But just having a model for a different kind of life, he says, completely transformed how he understood himself.

“Just through the process of listening, I felt not alone – which is the great irony of the name: ‘Solo,’” Mr. Trout says.

Mr. Trout drove five hours to Denver to attend Dr. McGraw’s “Solo Salon.” He’s taken small tips to heart, like having clothes tailored or trying new experiences. And now he’s also meeting his neighbors more, planning projects at home, and engaging in civic activities he hadn’t even considered before.

Ms. Eaton, too, has consciously cultivated deep friendships. “I can truly say that the friends I have now God has definitely placed in my life. ... They can give me, you know, as the saying goes, ‘reproof in love.’”

She’s also organizing local face-to-face meetups via online apps, putting together virtual book clubs, and organizing events such as outdoor backpacking for beginners.

But not every solo is what Dr. DePaulo calls “single at heart.” Dr. McGraw lays out four categories he's generally found: “Somedays” think it’s important to find a lifelong partner; “Just Mays” still think they might find someone, but they wouldn’t feel regret if they didn’t. “No Ways” are those not looking at all, and “New Ways” are interested in romantic relationships, but not a traditional one.

Mr. Trout falls into that final category. “At my deepest desire, I want to fall in love,” says Mr. Trout. “But what that means is different than it used to mean. I used to think of that as, oh, get married, have kids, get the house, the job, the money. Potentially, I would find someone that, maybe we live in separate households, but we’re together. We are supporting each other, we’re traveling together. We are in love.”

There are significant drawbacks for those wishing to remain single. It often requires a higher level of affluence and social status, since one of the primary benefits of living as a couple are traditional economies of scale.

“And there is a whole generation of single people now who are Gen Xers or older millennials, and what’s going to happen to us when we’re old and we don’t have children to take care of us?” says Ms. Reiter. “We don’t have a spouse to take care of us, or that can give us a sense of purpose as we take care of them. Some of us joke, we’re probably going to have to have these single-women dormitories when we’re in our 80s and 90s, or borrow our nieces and nephews often to take care of us.”

Dr. McGraw, too, notes that the rise in singles across the country includes lower-income men – many of whom are not single by choice, who are starting to be left behind both socially and economically – a trend also noted in the Pew study.

“When you have young men who are adrift, without purpose and without connection, consuming too much pornography and playing too many video games, that is bad,” he says.

“I was involuntarily celibate in my 20s because I just had no skills,” he says. “So some of these men will improve and compete and figure it out. But then the worry is, the guys who don’t will be the ones who become misogynistic, angry, bitter, and blame women for their situation in life.”

After decades of advocating for those who are “single at heart,” Dr. DePaulo is starting to see the cultural needle move as single people become more visible and vocal about their needs.

“They are the people who live their best lives – their most meaningful, fulfilling, and authentic lives – by living single,” she says. “Many of them spent a long time trying to force themselves onto the path of romantic coupling, because they never heard of such a thing as living your best life by living single. That’s not fair to them. It is also not fair to their romantic partners, who deserve to be with people whose best lives are coupled lives.”

Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 1967-2021; Pew Research Center

Room for everyone: Tribal college expands its reach

Can a tribal college support its own community’s culture while also enrolling students from many other Native American groups? This story looks at how to balance preservation and inclusivity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Marisa Agha Correspondent

During the pandemic, Tohono O’odham Community College, founded in 1998 to serve its tribe, moved all its courses online and offered them without charge to any Native student.

Enrollment nearly doubled to more than 900 students. Tohono O’odham had the largest increase of any tribal college – 96% in 2020.

There are now 55 tribal nations represented among students where there used to be eight or nine, says Paul Robertson, president of the college. The increasing diversity has raised questions about the small college’s identity and the best way for it to contribute to Native education.

College deans, faculty, and employees have talked together in recent weeks to address what initially Dr. Robertson says was “an existential crisis” that raised the question: “What are we?” The school has since decided it “can accommodate the changes and still maintain our identity,” the president notes.

Josie Pete of the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah found the college a year ago. The online classes and free tuition allowed her to study from her home on the Utah reservation.

“It was something that was convenient,” she says. “I didn’t really have to wonder, ‘How am I going to pay for school? How am I going to pay for books?’”

Room for everyone: Tribal college expands its reach

Deep in the Sonoran Desert, near the Arizona and Mexico border, picnic tables under ramadas at Tohono O’odham Community College sit empty. A new amphitheater for songs, prayers, and ceremonies is silent under a November sun.

But the college, located on the Tohono O’odham Nation, about an hour west of Tucson, has more students than ever – just not on campus.

During the pandemic, the college, founded in 1998 to serve its tribe, moved all its courses online and offered them without charge to any Native student. Enrollment nearly doubled to more than 900 students. Tohono O’odham had the largest increase of any tribal college – 96% in 2020.

Students liked online courses and free tuition so much that when the college reopened this fall, they didn’t return to campus. And the college grew more diverse. There are now 55 tribal nations represented among students where there used to be eight or nine, says Paul Robertson, president of the college. The increasing diversity is changing the composition of a campus rooted in serving the Tohono O’odham people, prompting concern about the small college’s identity and the best way for it to contribute to Native education.

College deans, faculty, and employees have met together in recent weeks to address what initially Dr. Robertson says was “an existential crisis” that raised the question: “What are we?”

The question echoes throughout Indian Country, as tribal colleges and universities, largely federally funded and founded to serve their specific communities, strive to meet a vast need among Native students for higher education.

The colleges “counter some really negative forces in our culture in terms of giving up your background,” says Jon Reyhner, professor of education at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff and co-author of “American Indian Education: A History.” “Knowing your history breeds resilience.”

The Tohono O’odham Nation founded its college, one of about 35 tribal colleges nationwide, with the aim of preserving the culture and traditions of a people whose ties to the region date back thousands of years. But Dr. Robertson, the college president, says the immense need among all Native students suggests the college has a purpose beyond its tribe. “There’s a lot of students out there,” he says. “I think we’re starting to see that.”

Josie Pete of the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah says she likely would not have been able to enroll at Tohono O’odham Community College a year ago without the availability of online classes and free tuition since she was working from her home on the Utah reservation.

“It was something that was convenient,” she says. “I didn’t really have to wonder, ‘How am I going to pay for school? How am I going to pay for books?’”

Ms. Pete wanted to study art and the college sent her supplies, including sketchbooks, pencils, paints, and charcoal. “The school believed in me enough to send me the supplies,” she says. “It was just really special.”

Though she is from another tribe, Ms. Pete says she has enjoyed taking the required Tohono O’odham language and history classes. “I’m actually all for it,” she says. “It’s unique to learn about another culture that is similar to my own.”

When she finishes in about a year, she intends to go to a four-year institution where she also can study online for a bachelor’s degree in art, and eventually become an illustrator.

Feeding a hunger for education

Tohono O’odham Community College has been able to accommodate additional students, like Ms. Pete, through a combination of federal funds and support from the Tohono O’odham Nation, which provides about 42% of the college’s annual budget, according to Dr. Robertson. Federal funding to tribal colleges and universities is only given for Native American students, who make up 95% of students at Tohono O’odham.

The school is a model for what other tribal colleges and universities can achieve through developing a strong online presence, says Carrie Billy, president and CEO of the American Indian Higher Education Consortium.

“That’s exactly how we want to serve Native people, wherever they are,” Ms. Billy says. “There’s a hunger for culturally grounded education.”

Drawing Native students from all over online can only bolster college attainment among American Indians, says Ofelia Zepeda, chair of Tohono O’odham Community College’s Board of Trustees and Regents’ professor of linguistics at the University of Arizona in Tucson. “It’s just great to see because it has been so long in coming.”

American Indian graduation rates have long been a struggle: 15% of American Indians and Alaska Natives age 25 and older have a bachelor’s degree or higher compared with 32% of Americans in that age group, according to census figures. In Arizona, home to one of the nation’s largest Indigenous populations, the numbers for both groups lag even more, with 11% of American Indians and Alaska Natives age 25 and older holding a bachelor’s degree or higher compared with 29% of Arizonans in that age group.

Studies have shown that the culturally enriched experience at tribal colleges feeds students’ success. Native language, culture, and history courses about their tribes are key to the curriculum. That’s the point of a tribal college or university – to build and reclaim community. Schools are evaluated based on their tribe-specific relationships. The tribal college movement of the late 1960s and 1970s grew out of the oppression and frustration many American Indian children experienced after decades of forced assimilation to Western customs in boarding schools. Most tribal college graduates stay on or return to their reservation.

The Tohono O’odham Nation, one of the nation’s largest in land area at nearly 3 million acres, has about 34,000 enrolled members, including those who live in Mexico, says Bernard Siquieros, vice chair of the college’s board of trustees.

The tribe founded the college to “provide an opportunity for our young people to have a good starting place in their higher education journey,” Mr. Siquieros says. The teaching of the nation’s language, history, and culture – known as Himdag – is a key part of the curriculum. But welcoming students from other tribes helps all Native students and the college, he says.

Still, the college balances that with its original mandate. Some students from other tribes ask about taking a class in their own tribal language, but that’s not what Tohono O’odham Community College is, says Alberta Espinoza, college counselor. Students understand, she says, when she tells them, ‘This is Tohono O’odham Community College,’ and they don’t have to pay any tuition as a Native student, she says.

“The universal Indigenous world view is like, ‘This is a gift,’” Ms. Espinoza says. “You just don’t look a gift horse in the mouth. And so, you be respectful. You take what is given to you and then you move on from there.”

“It felt like a family”

Officials want students back at the physical campus, offering incentives like free meals and gas vouchers. And there are plans for a completed wellness center and a four-year degree in Tohono O’odham studies.

Caralina Antone, now working toward her bachelor’s degree at Arizona State University, credits the college’s supportive atmosphere with helping her get back on the college path.

“They continued to encourage me,” she says. “It felt like a family. … You’re not alone.”

Many Native people, like Ms. Antone, live in urban areas but want to attend tribal colleges, which are often in rural and remote places. Ms. Antone, an orphan raised by her grandmother, wanted to go to Tohono O’odham’s college because that was her grandmother’s tribe. At first, she commuted nearly six hours daily from the Phoenix area to the college and back. “I got up at 3 a.m. to be out the door by 4:30,” she says. “I wanted to honor her and complete school.”

She missed having in-person classes after the pandemic started, but adapted to the online work. She was the college’s student of the year when she graduated in 2020. She hopes to become a social worker and help adolescents.

“You need to finish what you start,” she says. “I’m glad I got through it.”

Tohono O’odham Community College officials met last week and are “united” that the college’s “mission will continue to be the same” as the college faces a future rooted in serving students from many more tribes, Dr. Robertson explains in an email.

“Through much discussion we have reached a consensus that we can accommodate the changes,” he notes, “and still maintain our identity.”

Points of Progress

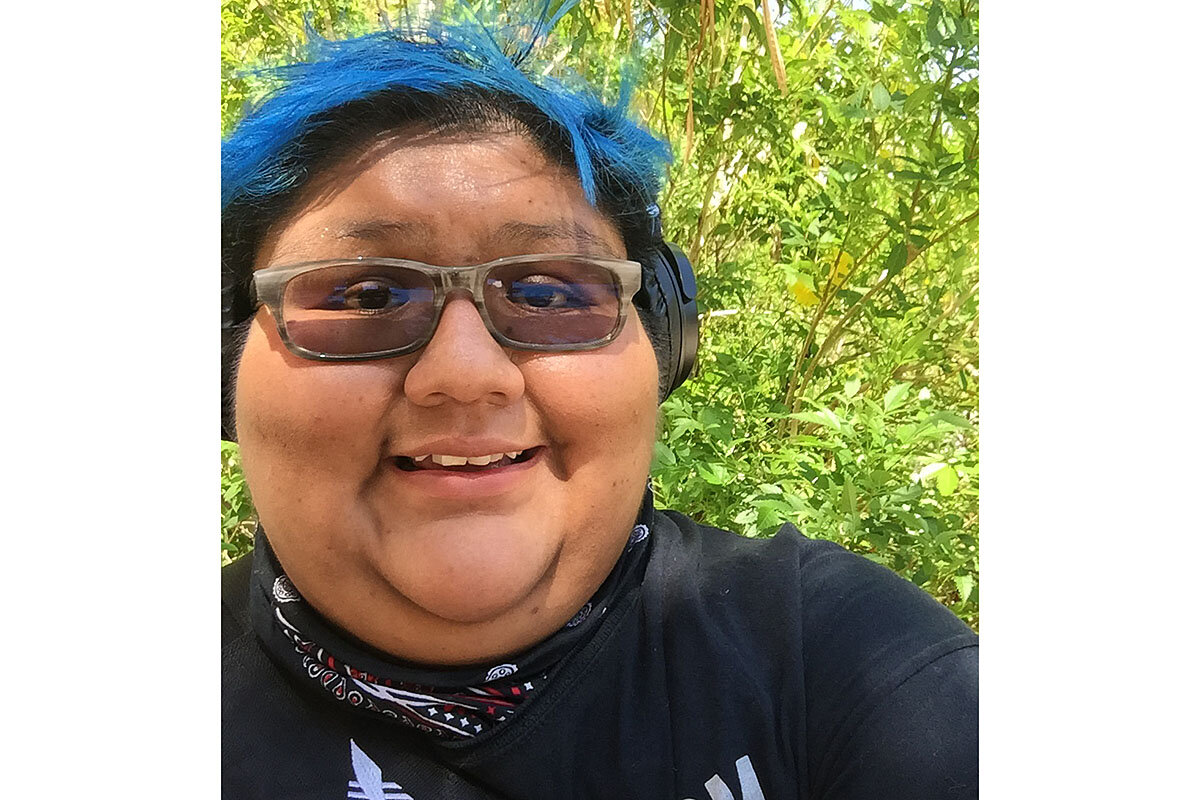

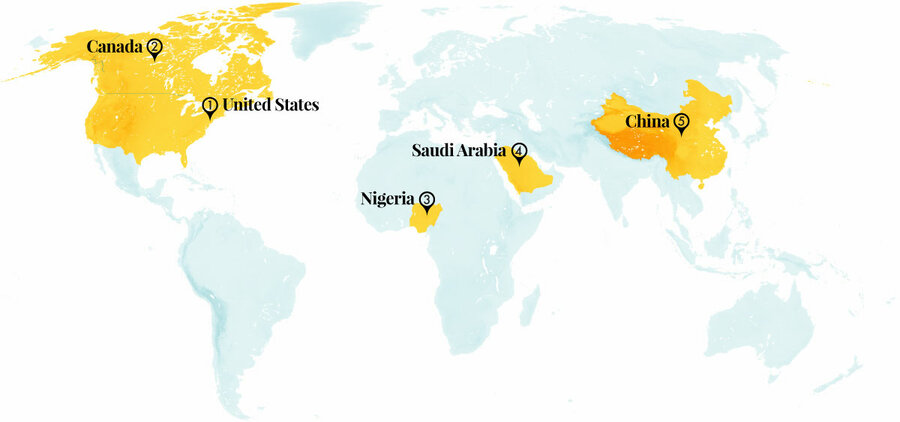

Low-level traffic stops decrease; Saudi women in the workplace increase

In our progress roundup, we find governments are giving more freedom to those who’ve been denied it, and size up some of the outcomes – from more humane policing in the U.S. to more work opportunities for women in Saudi Arabia.

Low-level traffic stops decrease; Saudi women in the workplace increase

In growing recognition of how policing of roadways affects people differently, communities are putting the brakes on drivers being pulled over for infractions such as a broken taillight.

1. United States

Philadelphia is banning low-level traffic stops. Civil rights groups have long noted how low-level traffic violations are disproportionately levied against Black drivers. Black people make up less than half of Philadelphia’s population, but accounted for 72% of traffic stops from October 2018 through September 2019. Pretextual stops are a means of racial profiling, say advocates, and degrade trust between the community and law enforcement.

City Councilmember Isaiah Thomas worked with local law enforcement to develop the Driving Equality Bill, which prohibits traffic stops for minor violations such as a broken taillight or a small item hanging from a mirror. “To many people who look like me, a traffic stop is a rite of passage. ... We plan our social interactions around the fact that it is likely that we will be pulled over by police,” said Mr. Thomas. Police can still ticket motorists by mail. The bill will go into effect early next year after officers are retrained. Although Philadelphia is the largest city to enact such laws, other state and local governments, including the state of Virginia and city of Minneapolis, have also adapted traffic stop policies.

CNN, NPR

2. Canada

A startup is harnessing drone technology to boost reforestation in Canada and beyond. Boreal forests store nearly twice as much carbon as tropical rainforests. Traditional reforestation efforts are struggling to keep up with the growing threat of forest fires and logging, but the Toronto-based company Flash Forest sees a solution.

The group retrofits drones to release 3D-printed seed pods – pre-germinated seeds, nutrients, and fungi – with computer-programmed precision. Each machine dispenses pods at nearly 10 times the rate of planting by hand, and one pilot can operate five drones at a time. This spring, the team used drones and aerial mapping software to plant hundreds of thousands of seed pods containing 19 species across 13 pilot sites in Canada, including burn sites in northern Alberta and Ontario. While it will be some years before the seedlings mature and the success of these missions can be accurately assessed, the Flash Forest team has committed to planting 1 billion seed pods by 2028.

The Washington Post, Canadian Business, Forbes

3. Nigeria

A solar battery startup is making green energy more accessible in Nigeria. Due to utilities mismanagement, half of the country’s electricity needs are met through self-generated power, and many Nigerians rely on expensive, polluting diesel generators to manage rolling blackouts. But customers of a corner store have an alternative: Shoppers can rent a portable, solar-charged lithium battery.

In Lagos, Reeddi collects the empty batteries and recharges them off-site. In the future, it plans to automate this process by installing solar-powered vending machines to charge the batteries. Each Reeddi capsule costs 50 cents per day and has ports to charge phones, lamps, laptops, and similar devices. The modular design also allows users to combine capsules to meet heftier power needs. Reeddi is working to expand services throughout Nigeria, bringing a reliable and affordable energy solution to communities in need. The clean technology startup was a finalist for the £1 million ($1.36 million) Earthshot Prize for its effort to eliminate barriers to green energy. “Our goal is to make energy access as easy as buying milk,” says CEO Olugbenga Olubanjo.

Freethink, Fast Company, Earthshot Prize

4. Saudi Arabia

More women are entering the Saudi workforce amid social and political changes. Saudi Arabia’s efforts to modernize – combined with recent government subsidy cuts and taxes – are drawing more women into the labor market. Today, 33% of workers are women, double the 2016 figure. Although the nation’s few working women were previously restricted to positions as teachers or medical personnel to maintain gender segregation, women of different ages and education backgrounds are now entering new spheres, including supermarkets, restaurants, and private firms.

The country is still committed to conservative traditions, and men hold the vast majority of power. King Salman’s Cabinet features no women, the country’s gender pay gap is 49%, and harassment and exploitation remain a problem. However, observers say norms are shifting, and looser restrictions on gender mixing and male guardianship are opening up new possibilities. There are more than 900,000 Saudi women working in private firms today, says economist Jennifer Peck, up from 56,000 in 2010. And those who’ve been working for decades are seeing more confidence among their female colleagues. “In my day, we were too scared to even ask for a salary,” says Rana Alturki, who has worked at her father’s oil and gas firm since 2000. “But girls these days – they come in and negotiate hard. They know their worth.”

Reuters

5. China

China’s wetlands are showing signs of recovery after decades of decline. Although they harbor vital plant and animal species and help sequester carbon, coastal wetlands are among the world’s least-protected ecosystems. A 2018 intergovernmental report found that the world lost 35% of global wetlands between 1970 and 2015. China lost about half its coastal wetlands in the latter half of the 20th century as the country opened to international trade, sparking development in coastal zones.

However, a recent analysis of satellite imagery from 1984 through 2018 shows China’s wetland areas rebounding after 2012. The study, conducted by a team of international scientists and published in the journal Nature Sustainability, suggests that government conservation programs are yielding results in three types of wetland areas: mangroves, tidal flats, and salt marshes. It is one of the first studies to use satellite technology to assess changes to wetland habitats nationwide. “It’s encouraging that we start to see some improvement in coastal wetlands,” said lead author Xiangming Xiao. “It’s demonstrated that there is still hope.”

Mongabay

Difference-maker

To clean up East Baltimore, this mentor shores up buildings – and youths

And here’s some progress being driven by a difference-maker: To change the way a neighborhood looks, an East Baltimore youth mentor helps young men look within themselves to find the power to become community leaders.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When Munir Bahar talks about building pillars of community – he’s talking about not just the young men he mentors, but also the buildings and streets those young men inhabit.

At age 20, after troubled teen years in and out of incarceration, he made the decision never to go back to jail and started thinking about organizing what would eventually become the COR Health Institute – Committed, Organized, Responsible – a “prevention-based” organization that aims to deter violence in an East Baltimore ZIP code that had 31 homicides last year.

Surrounded by vacant properties and violence, COR – operating out of a rehabbed liquor store and run-down row houses – enlists young residents to improve their neighborhood. In addition to community cleanups and food drives, COR teaches schoolchildren to stay fit.

“You teach them to look within themselves to find power,” says Mr. Bahar, a tax consultant by trade, whose passion is teaching the discipline of martial arts. “I can’t save them financially, I can’t give them a new house ... but if I can teach them to be stronger individuals ... more faithful, more patient, more resilient, then whatever the world may take them through, I’ll know they’ll be better off.”

To clean up East Baltimore, this mentor shores up buildings – and youths

Munir Bahar, sitting erect and intensely focused, is a commanding presence in the crowd that’s come to see his latest crop of leadership graduates. Six young men – who came through tough streets in East Baltimore to be trained here to go right back out and improve their community – project the posture and confidence of their leader. Each takes the microphone to explain what they’ve learned in the 10-week course to foster character and leadership development at COR Health Institute.

“Every great leader follows or has followed another great leader,” observes Khyree Green, a 24-year-old who wandered into a COR trash-pickup event two years ago, spent the day watching and listening to Mr. Bahar walk his appealing talk of healthy citizenship, and followed him into this program of martial arts, fitness training, and civic engagement.

Three generations of leaders in this room illustrate the model the young man describes: Ademola Ekulona, elderly now, was the youth leader who tried to keep the young Mr. Bahar out of jail in the 1990s. He proudly watches his protégé’s protégés describe leadership lessons. They are lessons that seem to boil down to the hard work of disciplining themselves to stay calm with a boss at work, to take responsibility for and stick to a hard task like a long workout or getting good grades, and to just do the “right thing.”

Mr. Green says his defining moment with COR was the day he was one of two young men left standing after grueling hill sprints with a medicine ball: “You learn discipline ... that day, right there, let me know that I was in it and I wanted to do it.” Now, in addition to holding down a job at a local gas company, he’s reading books and says he’s thinking more positively because of “big brother” Munir Bahar. And, likewise, Mr. Green led his own actual younger brother and fellow graduate, 19-year-old Phillip Brooks, into the transformational program.

COR – Committed, Organized, Responsible – is a “prevention-based” organization that aims to deter violence in an East Baltimore ZIP code that had 31 homicides last year. Surrounded by vacant properties and violence, COR enlists young residents to improve their neighborhood. In addition to community cleanups and food drives, COR kept watch last year to ensure the local protests over the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis remained peaceful.

COR is all about creating “assets” – pillars of the community to hold it up, explains Mr. Bahar, who founded and runs the nonprofit.

“You have to literally change the infrastructure [and put in place] what I call community assets,” says Mr. Bahar, who speaks both of individual lives and the East Baltimore neighborhood he’s improving. The sparkling COR building, where the graduation ceremony was held, was rehabbed from the ruins of a liquor store and row houses by Mr. Bahar and neighborhood youth.

Since the COR team transformed the building into a gym and learning space in 2017, Mr. Bahar says there has been no gun violence on this block of North Collington Avenue.

“You teach them to look within themselves to find power,” says Mr. Bahar, a tax consultant by trade, whose passion is teaching the discipline of martial arts. “I can’t save them financially, I can’t give them a new house ... but if I can teach them to be stronger individuals, if I can teach them to be more faithful, more patient, more resilient individuals, then whatever the world may take them through, I’ll know they’ll be better off.”

Mr. Bahar has traveled this road himself.

“Help me with this boy”

Two blocks away from the institute is a church where – during the 1990s – the seeds of COR were planted in an after-school program called the Harambee Rites of Passage Kollective.

“[Munir’s] mother came in and said, ‘You gotta help me with this boy. He’s driving me crazy,’” recalls Mr. Ekulona, a Harambee facilitator at the time.

By his own recollection, Mr. Bahar says, “I was bad as hell,” smoking, drinking, selling drugs, put out of school multiple times.

“We would have meetings about, ‘What are we going to do about Munir?’” says Mr. Ekulona, who recalls after-

school program staff saying, “He’s just wild.”

“No,” Mr. Ekulona recalls responding. “[Munir’s] just telling us what he needs.”

Despite the best efforts of his mother and others, says Mr. Bahar, “from 13 to 20 years old, I was in and out of jail.”

At age 20, he made the decision never to go back to jail and started a community organization, a predecessor to COR. Though he didn’t always listen as a teenager, Mr. Bahar says the activities Mr. Ekulona ran at Harambee helped him recognize the wisdom – the “internal tools” of “values and principles” – youth need to be successful.

In other words, he wanted to build pillars of community. By developing the physical and mental health of young people – to back their self-esteem – the social and physical landscape of poverty-ridden neighborhoods can change, he believes.

Now, the walls of the institute are filled with photos of Mr. Bahar teaching schoolchildren to stay fit and focused through martial arts, leading anti-violence marches, and building projects.

Sitting on an easy chair in the institute’s spotless foyer, Mr. Bahar calls the construction of the institute the “hardest project I’ve ever done in my life.”

Going through the city’s Vacants to Value program to purchase the properties for $1,000 apiece in 2016, Mr. Bahar worked as a plumber, an electrician, and a carpenter on the project, in addition to piecing together and directing a construction crew of young people over the monthslong effort.

Since then about 60 youths of all ages have been through programming at the facility – COR leadership for youth, an after-school partnership, and those involved with karate classes.

“When you got [people] who are lifting [weights] and doing martial arts together, you’re building a natural bond,” says Mr. Bahar. “That’s why once you put a facility like this in a community, it is going to build the bond of the residents of that community.”

Building civic sinew

These community connections are a big component of a healthy and sustainable neighborhood, says Seema Iyer, director of the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance, which provides quality of life data for the city’s neighborhoods.

She says the work of restoration by the COR Health Institute is a part of a larger trend in East Baltimore. “There’s a lot fewer [building] vacancies today than there were 10 years ago.”

On COR’s October graduation night, the building was full, with two local TV news crews, community members, and the graduates.

Phillip Brooks, the evening’s youngest graduate, emphasized how he learned leadership by example, like his brother Mr. Green. Leadership is “not just about wanting or expecting people to follow you. It’s more doing the right thing when no one is looking,” he tells the crowd.

What that means, he explains later, is putting his all into whatever he does: “I was never the straight-A kid. ... I always did the bare minimum.” But now, he has come to believe, he says, that when “putting your all into everything, you notice the difference in your life: More opportunities open up.”

As the graduation ceremony came to an end, Mr. Ekulona, who counseled Munir as a teen, spoke: “I listened to each of these six men. I hear leaders, I hear people of courage, people of integrity, and this is why I am so pleased.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The gig work problem: Who is an employee, anyway?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The booming gig economy has shaken up the world of work, raising a fundamental question: Who is an employee, anyway?

Today anyone can download an app and start a business. Companies like Uber act as fixers between those seeking services (a ride to the airport, a meal delivered) and those offering them.

Gig work has been a boon to millions of people. But critics say it can be nothing more than fake self-employment in which they really are employees – without fringe benefits.

Last week the European Commission announced the biggest effort yet to bring light and fair play to the murky world of gig work. Its proposed rules would set clear standards for determining who is a gig worker or an employee.

According to the European Union, the goal is not to try to kill, or even hamper, the expanding gig economy, which may grow to some 43 million workers in the 27 EU countries in the next few years.

Where gig work is exploiting workers, it’s a step backward. Efforts to put in place rules that ensure fair play between employers and gig workers could benefit everyone.

The gig work problem: Who is an employee, anyway?

The booming gig economy has shaken up the world of work. It’s also raised a fundamental question: Who is an employee, anyway?

Today anyone can download an app and start their own business. Some of the most visible gig workers are drivers who use their own vehicles to deliver people, food, or other goods. Companies like Uber, using algorithms, act as fixers between those seeking services (a ride to the airport, a meal delivered) and those offering them.

Gig work has been a boon to millions of people. It offers many advantages including flexible work hours and the ability to pick and choose what work to accept.

But does it? Critics say that in some cases gig work has been nothing more than fake self-employment in which workers’ freedoms are so restricted they amount to being employees – but without the fringe benefits employees enjoy.

Last week the European Commission announced the biggest effort yet to bring light and fair play to the murky world of gig work. Its proposed rules would set clear standards for determining who is an employee (and deserving of the benefits of an employee) and who is a self-employed contractor.

For example, the commission said, if companies don’t allow their gig workers to work for other companies, have rules regarding employee appearance, and require specifics about exactly how tasks must be carried out, they may have turned their gig workers into employees.

Under the new rules, gig workers could not be fired via automated computer algorithm without explanation. Any important decisions regarding them would be conveyed through a human contact. Most importantly, employers, not the gig workers, would be asked to prove whether or not their gig workers were employees.

The goal is not to try to kill, or even hamper, the growing gig economy, Nicolas Schmit, the European Union’s jobs and social rights commissioner, said last week. What it comes down to, he said, is “ensuring that these jobs are quality jobs. ... We don’t want this new economy just giving low-quality or precarious jobs.”

Gig work includes more than drivers. Potentially, they're anyone who uses an app to seek out work. For example, many are home cleaners or home health aides. The EU says the proposed rules might affect up to 4.1 million gig workers out of the estimated 28 million in the 27-country EU. That number may reach 43 million in the next few years.

The rules are expected to take years to finalize. Pushback will come from Uber and other companies that are concerned too much regulation will restrict tech innovation in the workplace, depriving customers of convenient, affordable services they have come to depend on.

But any new system that exploits workers is a step backward. Efforts to put in place rules that ensure fair play between employers and their gig workers can benefit everyone.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The good news of the Comforter

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Margarita Sandelmann Thatcher

Though the physical Jesus is no longer here, the eternal Christ he lived and shared is ever present to comfort, heal, and light our path forward.

The good news of the Comforter

Too often, the news we encounter – whether in headlines or in our own families and lives – is a mixture of good and bad.

Yet there is good news we can count on every day and that empowers us to meet and overcome challenges. It’s found in the Scriptures, and particularly highlighted in the Gospels. In fact, the word “gospel” comes from a Greek word meaning “good news.”

What better news can we tune into each day than the assurance that God, divine Love, is a loving Father-Mother to us all; is always present; and infinitely loves, sustains, and cares for every one of us?

This good news is as accessible and practical today as it was 2,000 years ago, when Christ Jesus demonstrated God’s power and goodness through his teachings and unequaled healing works. In our moments of uncertainty or fear or grief, this Christ message can bring comfort and healing – evidence of divine law in action.

Jesus referred to this spiritual law as the Comforter that would bring us “into all truth” (John 16:13). This Comforter is neither mysterious nor far off but here at hand and practical, for each of us to find.

Some time ago, during several years of caring full-time for two greatly loved family members, I began to sink into a kind of thinking that was unusual for me. I felt needy, alone, and helpless – perhaps somewhat like the man in a biblical account whom Jesus encountered at the pool of Bethesda (see John 5:2-9). This man, who had been incapacitated for many years, was waiting by the pool, seeking someone to help him into the water, which was said to have healing properties when an angel moved upon it. He did not recognize the Christ and Comforter right there and ready to heal right then.

In my case, the thought “If Jesus were still here, he would help me” came to mind repeatedly, an almost daily yearning. But this thinking was unproductive, especially because I’d learned through my study of Christian Science to think of Christ in more eternal terms than just the historic person of Jesus. I’d learned to think of Christ as divine Truth, speaking to my consciousness.

In his promise of the Comforter, Jesus revealed the eternal presence and availability of the Christ. He assured his followers that they would never be alone or helpless, because the Comforter – expressing God’s tender love – would always be present to supply their needs.

Mary Baker Eddy, a devoted follower of Christ Jesus and the founder of this news organization, illustrates the distinctness and inseparability of Christ and Jesus in this illuminating passage: “Jesus was born of Mary. Christ is the true idea voicing good, the divine message from God to men speaking to the human consciousness” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 332).

I realized that instead of longing for the physical presence of Jesus, I could ponder his timeless Christly message and gain spiritual insight. I clung to his tender words, “I am with you alway, even unto the end of the world” (Matthew 28:20) and “I will not leave you comfortless” (John 14:18).

Over a period of months, as I prayed to God, our Father-Mother, my thought became filled with the Christ, Truth. I felt less needy and more hopeful of finding good in each day’s tasks. I felt a sweet assurance that God, our divine Parent, does indeed care for us, His spiritual offspring, impartially and continuously. This strengthened me and empowered my efforts to care for these relatives.

Even though the physical Jesus is not present with us today, his message of comfort and healing is available to us, and always will be. As we turn to this Comforter we become less dependent on other people for our happiness and stability. And those who are in our care are blessed by this as well.

These ideas have helped me through dark times and difficult situations. I still have challenges, but the feelings of helplessness have vanished. The thought “If only Jesus were still here” has been replaced by a glad affirmation, “The Christ is here and gives me comfort, strength, ability, joy.”

The Christ is here, fulfilling Jesus’ promise and revealing a divine purpose for each of us, wherever we are. And so, in the words of a loved hymn, “How can I keep from singing?” (Pauline T., “Christian Science Hymnal: Hymns 430-603,” No. 533, adapt.).

A message of love

Arctic fox

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Come back tomorrow. In the wake of the devastating tornadoes that tracked across six states over the weekend, we’re working on a broader story about the role of early warning alerts in keeping down loss of life amid increasingly powerful storms.