- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

In Today’s Issue

- ‘No one has food’: In bleak Afghan winter, a fight for survival

- A gerrymander foiled in Ohio? Reform advocates see a new model.

- Keepers of the flame vs. climate change reduction: Gas bans worry cooks

- They shrink. They grow. The tricky politics of national monuments.

- Kevin Day: Music transformed him. Now he aims to help others.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Why orchestras are finally starting to pass the baton to women

At age 9, Marin Alsop told her violin teacher that she wanted to become a conductor. The tutor’s response? “Girls can’t do that.” The New Yorker wasn’t deterred.

“This passion is so strong that it drove her through all of these setbacks and made her persevere,” says Bernadette Wegenstein, director of “The Conductor,” a documentary opening Friday about how Ms. Alsop became the first woman to lead a major U.S. orchestra.

This year, others are following her path. When the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra begins its 2022-2023 season, Nathalie Stutzmann from France will become the second woman to lead one of the U.S. majors. In Italy, Ukrainian-born Oksana Lyniv has been appointed director of the Teatro Comunale di Bologna. Finnish conductor Susanna Mälkki is reportedly a contender for the New York Philharmonic.

Grassroots groups, including the Taki Alsop Conducting Fellowship co-founded by Ms. Alsop, are helping women and musicians of color ascend the ranks of smaller orchestras. Progress also stems from changing perceptions about those brandishing batons.

“Traditionally seen as some kind of all-knowing, divine, mysterious, musical genius who was never questioned but always revered, conductors are now seen as, well … human,” writes Cynthia Johnston Turner, dean of the music faculty at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, via email. “We long for the day when we are just the ‘conductor’ and not the ‘female conductor.’”

“The Conductor” chronicles how Ms. Alsop’s groundbreaking appointment at the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra in 2005 led to a revolt by its musicians. She gracefully won them over. Now at Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra, Ms. Alsop continues to disprove the myth that only masculine traits are suitable for helming an ensemble from the prow of the stage.

“She shows that you don’t have to be this kind of personality in order for others to follow you,” says Ms. Wegenstein. “They follow you because they feel your art and they want to connect with you.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

‘No one has food’: In bleak Afghan winter, a fight for survival

With Afghans facing the confluence of Taliban rule, a collapsed economy, and growing food insecurity, a Monitor reporter searched for the human face of the humanitarian crisis.

Afghans have known the bite of hunger before, but say this winter is bleak like no other: The Taliban now rule; a hard winter has followed a severe drought; and jobs and cash have disappeared as the economy collapses and food prices soar.

“Last year was nothing like this,” says Latifa, a mother of eight, waiting in line for World Food Program rations in Logar province, south of Kabul. “Many people I know are in a critical situation this year. No one has food.”

Recognizing the scale of this winter’s crisis, the United Nations this month launched its biggest-ever appeal for any single country, seeking $4.4 billion for Afghanistan to “scale up and stave off widespread hunger, disease, malnutrition, and ultimately death.”

The U.N. estimates that 22.8 million Afghans – more than half the population – will be “acutely food insecure” in 2022, with 8.7 million of those deemed “at risk of famine-like conditions.”

For many, survival is a brutally simple calculation of changed circumstances, with food prices having doubled since August.

“Last year I had a job, I didn’t need any help,” says Mohammad Qassim, a jobless worker with eight children. “This is the first time in my life I stand in line.”

‘No one has food’: In bleak Afghan winter, a fight for survival

With snow falling across the frozen landscape, scores of desperate Afghans wait in line for World Food Program rations in Logar province, south of Kabul.

“We really need this food. If we don’t receive it, my children will go hungry,” says Latifa, a mother of eight, speaking through her faded-blue burqa.

Latifa signs for her family’s quota of flour and oil with a purple-ink thumbprint. A single loose thread hangs from the blue mesh that covers her face amid a scene of deprivation being repeated in every province across Afghanistan.

Afghans have known the bite of hunger before, but say this winter is bleak like no other: The Taliban now rule; a hard winter has followed a severe drought; and jobs and cash have disappeared as the economy collapses and food prices soar.

“Last year was nothing like this,” says Latifa. “Many people I know are in a critical situation this year. No one has food.”

The monthly ration is not enough, she adds, yet declares: “But we will survive.”

Recognizing the scale of this winter’s crisis, the United Nations this month launched its biggest-ever appeal for any single country, seeking $4.4 billion for Afghanistan to “scale up and stave off widespread hunger, disease, malnutrition, and ultimately death.”

The U.N. estimates that 22.8 million Afghans – more than half the population – will be “acutely food insecure” in 2022, with 8.7 million of those deemed “at risk of famine-like conditions.”

While poverty and hunger have been fixtures in Afghanistan during 40 years of war, the perfect storm of crises now has made Afghans increasingly reliant on social and family networks as safety nets, to prevent worst-case scenarios like starvation.

Latifa says a case in point is her family, which receives crucial help from friends and neighbors.

Sakina, the next woman in line at the WFP distribution in Pul-e-Alam, the provincial capital of Logar, says her family, too, receives such assistance.

Sakina was shot in the hand and the back last year at a police checkpoint, in a case of mistaken identity, she says. She lost a thumb and finger in the incident; her husband died in crossfire, long ago.

“We only have old, dried-up bread from neighbors,” says the mother of nine, whose worn brown shawl is draped to expose just one eye to the elements.

Changed circumstances

For many Afghans, the acute crises have forced them to stand in food lines, even as many markets in the capital, at least, appear to be stocked with fresh produce.

“Last year I had a job, I didn’t need any help,” says Mohammad Qassim, a jobless worker with eight children. “This is the first time in my life I stand in line.”

“The situation in one year has completely changed,” says Hamidullah Behesh, an Afghan contracting partner with WFP who works in Logar and Paktia provinces. The U.N. is so far targeting 2,250 families in Pul-e-Alam, but the need is three times greater, he says.

“This year, war and drought affected everyone,” says Mr. Behesh. Many jobs are gone, and individuals connected to the former government no longer receive salaries.

“There is a very needy situation, especially in Logar, because people here depended on government jobs and on agriculture,” he says. To increase liquidity, the WFP is starting a six-month program providing roughly $70 per month to each family.

For many, survival is a brutally simple calculation of changed circumstances.

“Maybe in the markets you will find food. But the problem is the prices,” says Ingy Sedky, spokeswoman for the International Committee of the Red Cross in Kabul. Prices have doubled since August.

“A normal family, which doesn’t have any income anymore, can’t afford to buy food,” she says. “You have families of eight or more, so how can one person feed all these people without being paid? It’s impossible.”

More children begging

Indeed, evidence of Afghans’ increasing vulnerability is everywhere. Along the road from Kabul to Pul-e-Alam, for example, women wearing burqas stand in the falling snow to beg, their children at their feet on the frozen ground, or huddled close.

In Kabul, more children are begging on the street, clinging onto cars with their hands out, or washing windshields of vehicles stuck in traffic for the equivalent of a few cents.

Difficult cases can be found in therapeutic feeding wards of Kabul’s hospitals, like the Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health. Here, 5-year-old Setayesh sits listlessly on her bed, her face gaunt with hunger. It is the third time in a year she has been admitted.

“We don’t have enough food for her,” says Setayesh’s mother, Shazia. “If we had money, we would get food for her.”

Doctors at two hospitals say the current surge of severely malnourished patients so far has been limited. Indeed, visitors to Indira Gandhi last September – a few weeks after the Taliban seized control – found two or three severely malnourished children in each bed.

Today there are two dozen such cases, with one child to a bed.

Still, the growing scale of need is clear at one recent WFP food distribution site in the Jaie Rais area of western Kabul. As at the WFP site in Logar, a large banner makes clear that the food is “from the American people,” via the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Afghan relief workers went door to door, searching for the most vulnerable.

“There were more than 20,000 people, and all of them need it – but we selected 1,200,” says Mustafa Haidari, project manager for the Afghan Social Organization for Women (ASOW), which distributes food on behalf of the WFP.

“Expectations of people [for help] are very high, now there is no work, everyone is jobless,” says Mr. Haidari. “One year ago there was need, but not like now.”

Wheelbarrows are stacked with a 110-pound bag of flour, a carefully weighed sack of lentils, a jug of oil and large pack of salt – enough for a family for a month. Scores of men and some women line up around the corner on the cold, clear morning.

“The world needs to pay more attention to Afghanistan; the situation is not acceptable,” says Marzia Mohammadi, director of ASOW.

Swirling among those in the WFP line is a rumor started last fall that eight children from one family perished from starvation, in a poor district on the western fringe of Kabul.

That “news,” first posted on Facebook with details and even a phone number, shocked Mohammad Rasoul Nowruzi, a district leader from that impoverished neighborhood, called “Twelfth Imam.” He helped mobilize 120 local leaders to search for the lost family, but found no evidence it ever existed.

But would the loss of an entire family from hunger be possible? Not without even greater deprivation, says Mr. Nowruzi, due to Afghans’ well-practiced, informal support networks.

“We have a lot of families in a critical situation, with no food to eat and no wood to keep warm,” says Mr. Nowruzi. “Someone will give food or share their food.”

Sometimes, he says, local leaders have asked couples planning a wedding to forego a costly ceremony, and instead donate the cash to the poor.

Surviving “with God’s blessing”

Such help has been part of the coping strategy for Barat Ali, his wife, Hamida, and their three daughters. Health issues and winter are preventing Mr. Ali from polishing shoes in town, which once earned him the equivalent of 70 cents a day, though often just half that.

Living in a wattle and daub house in Twelfth Imam, Mr. Ali laughs when asked how he feeds the family.

“With God’s blessing,” he replies. “Every door closed by people, God will open.”

That includes local help, for a family that has yet to receive any foreign food aid. They are guests at other houses for meals, the family says, and try to get invited to weddings.

Hamida’s hands are black from making homemade lumps of fuel for heat. The crushed charcoal to make it “came from one neighbor,” and the necessary straw and manure “came from another,” she says.

“This year is the worst,” says Ms. Hamida. “I am very worried about the future.”

So are many residents of Twelfth Imam, who mistake a foreign journalist and district leader visiting people’s homes for U.N. or NGO officials listing the hungriest families.

Within an hour, a dozen residents tag along the icy alleys, urgently wanting to tell their stories of need. Mr. Nowruzi is their one link to outside aid.

“The only person is me,” he says. “All day and night, people knock on my door, asking for help.”

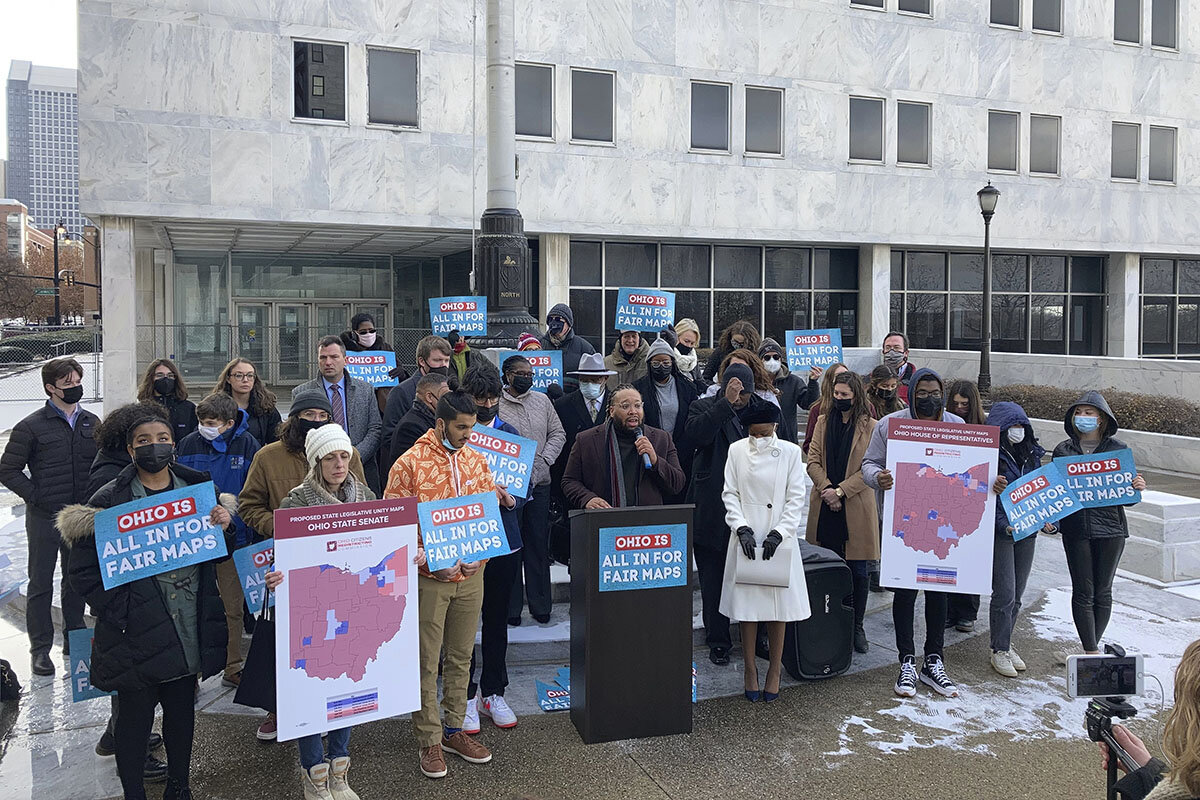

A gerrymander foiled in Ohio? Reform advocates see a new model.

The battle against partisan drawing of political districts is proving more complicated than reform advocates had hoped. In Ohio, a voter-passed measure at least gives courts a clear standard to uphold.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In recent years, citizen-led efforts to reform redistricting have largely focused on creating independent commissions. By taking politicians out of the process, the thinking goes, states might curb gerrymandering – the skewing of district lines for partisan gain.

Ohio took another path.

A redistricting commission made up of politicians from both parties draws its state legislative maps, while lawmakers in the Statehouse oversee congressional boundaries. But both sets of maps must comply with a voter-approved constitutional amendment that prohibits gerrymanders.

This month, the Ohio Supreme Court, with the Republican chief justice acting as the swing vote, rejected the state’s GOP-drawn districts. The congressional map would have created 11 Republican-leaning seats and two safe seats for Democrats, along with two competitive seats. The court compared this with average statewide vote shares of 54% for Republicans and 46% for Democrats.

Over the weekend, Ohio’s redistricting commission published a new set of maps that Democrats also refused to endorse, cuing up another court review.

“This Ohio case demonstrates state courts are perfectly capable of stepping in and applying standards of fairness to redistricting,” says Yurij Rudensky of the Brennan Center’s democracy program, which joined one of the lawsuits against the redistricting commission.

A gerrymander foiled in Ohio? Reform advocates see a new model.

In recent years, citizen-led efforts to change how states set boundaries for legislative districts have largely focused on the creation of nonpartisan commissions. The idea was to take politics, and politicians, out of the decennial process so that mapmakers could focus on fairness and curb gerrymandering – the delineation of districts for partisan gain.

Ohio took another path.

A redistricting commission made up of politicians from both parties draws the lines for Ohio’s state legislative seats, while lawmakers in the Statehouse decide on congressional maps. But there’s a catch: The maps must comply with a voter-approved constitutional amendment that prohibits gerrymanders.

This month, the Ohio Supreme Court took a hard look at the proposed maps and concluded they gave Republicans an advantage that didn’t reflect the political makeup of the state. In 4-3 rulings, with the Republican chief justice acting as the swing vote, the court ordered up more proportionate districts ahead of this year’s midterm elections – a rebuke to Republicans who hold three-quarters of Ohio’s congressional seats and a veto-proof majority in Columbus.

“When the dealer stacks the deck in advance, the house usually wins,” wrote Justice Michael Donnelly in the majority opinion.

The recent failure of Democrats to enact voting rights legislation in Washington has underscored the limits of federal oversight of how states run elections. Among other measures, the bill would have prohibited the types of gerrymanders that both parties have long employed for political advantage. Senate Republicans criticized the voting rights bill as federal overreach based on false claims of voter suppression.

The bill’s failure shows the need for reform advocates to focus on state laws, says David Pepper, a former Democratic state chair in Ohio. “We now have standards in court to enforce these new rules” in Ohio, he says.

The congressional map that the court rejected would have created 11 Republican-leaning seats and two safe seats for Democrats, along with two competitive seats. The court compared this with average statewide vote shares of 54% for Republicans and 46% for Democrats.

Over the weekend, Ohio’s redistricting commission published a new set of maps that Democrats also refused to endorse, cuing up another court review.

“I was hopeful that there would be a consensus between the Republicans and Democrats, but evidently that proved impossible,” said Secretary of State Frank LaRose, one of five Republicans on the commission.

One challenge in designing proportionate districts is the geographic sorting of Democrats and Republicans into urban and rural areas, with Democratic voters increasingly concentrated in cities. Republicans point out that the redistricting commission is mandated to draw “compact” districts that keep communities together, and that the GOP-favored maps would have done this. When he approved the congressional map back in November, GOP Gov. Mike DeWine called it “fair, compact, and competitive.”

Experts on redistricting agree that the criteria for drawing fair maps – proportionate to the state’s partisan leanings, but also with compact boundaries and competitive races – can be in tension with each other.

“If your goal is to draw competitive seats ... geographical sorting makes things quite difficult,” says Adam Podowitz-Thomas, senior legal strategist at the Princeton Gerrymandering Project. But, he adds, “it’s often used as an excuse why rough measures of partisan fairness can’t be achieved, and that’s not true.”

The clock is ticking: Feb. 1 is the deadline for candidates filing for primaries. The legislature has until mid-February to agree on maps for federal elections. Ohio is losing one of its 16 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, as one of seven states whose congressional delegation will shrink due to shifts in population.

“What we’re doing here in Ohio is critical. We want to make sure the people of Ohio have fair representation in Congress and in the Ohio Statehouse,” says Jen Miller, executive director of the League of Women Voters of Ohio, the lead plaintiff in the congressional redistricting case.

Legal challenges across the U.S.

In 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that partisan gerrymanders were “political questions” that federal courts had no clear way to adjudicate. That put the onus on state courts to hear lawsuits over redistricting, including alleged racial discrimination in drawing boundaries. Federal statutes on civil rights and redistricting also allow for such cases to be tried there.

Disputed 2022 maps are the subject of lawsuits in North Carolina and Wisconsin, two battleground states where Republicans have outsize majorities in the legislature as a result of aggressive gerrymanders in the last redistricting a decade ago. Both have Democratic governors who oppose the GOP-drawn maps that are being challenged in state supreme courts.

But Ohio’s constitutional amendment sets it apart from states where partisan maps are being litigated without any specific anti-gerrymandering laws on the books, says Douglas Spencer, an associate professor of law at the University of Colorado who studies redistricting.

While courts in North Carolina and Pennsylvania have struck down skewed maps in the past on the basis of constitutional safeguards for free and fair elections and equal protection, “that’s not explicitly about redistricting. There’s no guarantee about what fairness should be,” he says. “State courts have to uphold some kind of law, and those laws don’t exist in every state.”

In Florida, which gains a House seat this year, maps drawn by legislators must also satisfy voter-approved anti-gerrymandering amendments to its state constitution. In the last cycle, courts invalidated maps crafted by GOP consultants. Florida’s Legislature is now wrangling over new districts for 2022.

Ohio’s efforts to curb partisan mapmaking began with a defeated ballot measure to create an independent commission in 2012. Since then, several other states have adopted that approach, with mixed results.

In Virginia and New York, nonpartisan commissions deadlocked this cycle, so courts and legislators stepped in. Michigan’s commission was more successful in finding consensus, though Black lawmakers objected to how seats were drawn in and around Detroit. Other states adopting this model include Arizona and Colorado.

Watchdog groups that score maps for partisan bias say states with independent commissions still tend to produce fairer maps than those where lawmakers control the process, including in Democratic-run states like Maryland and Illinois.

“We played the long game”

After failing to create an independent commission, reform advocates in Ohio – a former swing state that now tilts Republican – tried another tack.

In 2015, voters were asked if they wanted a bipartisan commission to draw proportionate district lines. The proposal, which passed with 75% support, created a commission of four lawmakers, two from each side of the aisle, and three statewide executives, who are currently all Republicans. If lawmakers from either side object to the final maps, they must be redrawn after four years.

In 2018, voters approved by a similar margin a constitutional amendment to prohibit partisan gerrymandering, setting a legal standard to uphold.

“It still left the politicians in the room,” says Mr. Pepper, who worked on the reform campaigns. As Democratic state chair, he also raised money to help elect more Democrats to the Ohio Supreme Court. “We played the long game,” he says.

But the fact that most state justices are elected, unlike federal judges, highlights a weakness in anti-gerrymandering reforms that rely on judicial review.

“I think this Ohio case demonstrates state courts are perfectly capable of stepping in and applying standards of fairness to redistricting,” says Yurij Rudensky, a redistricting counsel at the Brennan Center’s democracy program, which joined one of the lawsuits against the redistricting commission.

But, he adds, state “judges don’t have as robust protections that insulate their judicial independence from political retaliation.”

Three of Ohio’s Supreme Court justices are up for reelection in November. Mark Weaver, a GOP strategist in Ohio, says Republicans will try to expand their court 4-3 majority in time for the next redistricting round in four years. The GOP-run legislature last year changed the ballot so that judicial nominees are listed with their party affiliation; previously they were only listed by name on the ballot.

“Given that our state leans red now significantly, and most people don’t research a lot about Supreme Court races, it’s not hard to predict that Republicans will do better on the court,” he says.

He also plays down the impact of the court’s rejection of the Republican-drawn maps, given the favorable political environment for Republicans right now in a state they already dominate. “The only question is will there be a veto-proof supermajority,” he says.

Keepers of the flame vs. climate change reduction: Gas bans worry cooks

Cities nationwide are banning new natural gas hookups in favor of clean energy sources, creating culinary angst for those who love gas cooking. It’s one reason many locales are banning the gas bans.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Natural gas emissions contributing to the problem of global warming are small compared with emissions from the largest polluters – transportation and electricity production. But dozens of cities from New York to San Francisco are banning gas hookups in new construction in an effort to get to zero emissions from future buildings.

Some of the noisiest reactions seem to be from those passionate about cooking with gas. Their culinary angst – along with reaction from advocates of fuel choice – has sparked a blowback of bans on the bans. Some localities and 19 states have passed laws to prevent restrictions on new natural gas connections.

“With all the progress that we’ve made over the last 10 years or so in terms of changes to the electrical grid with the shift away from coal, it’s now becoming the case that the next sector that should be the obvious target of policies to reduce emissions” is natural gas, says Jonathan Buonocore, research scientist at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Nora Singley, a professional food stylist, downplays the concern. Even though she prefers the control of heat that gas gives her in the kitchen, “it would just be a period of acclimating,” because there are good gas-free electric ranges.

Keepers of the flame vs. climate change reduction: Gas bans worry cooks

Humans have been cooking with fire for millennia. But, with concerns over greenhouse gas emissions rising, some cities are banning natural gas in the kitchens of the future, and creating a policy dilemma: Can we slow global warming and still eat well?

Dozens of jurisdictions from Brookline, Massachusetts, to San Francisco have moved to ban new gas hookups for heating and cooking, and New York City last month brought its heft to the trend, setting restrictions on fossil fuel usage in new buildings by phasing in emissions limits beginning next year.

Culinary angst over the bans among those who find flame cooking superior has sparked a blowback of bans on the bans. Some localities and at least 19 states have passed laws to prevent municipalities from restricting new natural gas connections. Also behind these actions: gas-industry lobbying for “energy choice” and broader legislative tussling along party lines.

“With all the progress that we’ve made over the last 10 years or so in terms of changes to the electrical grid with the shift away from coal, it’s now becoming the case that the next sector that should be the obvious target of policies to reduce emissions has changed,” says Jonathan Buonocore, research scientist at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Natural gas is now a key target, he says.

Pollution and safety concerns

Methane, released from natural gas systems, accounts for about 3% of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, a pollutant that contributes to climate change, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Concerns also exist about natural gas as an indoor air pollution source.

A clean energy advocacy group, RMI, estimates that by 2040, the New York City bill could eliminate the equivalent amount of a year’s worth of emissions from 450,000 cars.

While the natural gas contribution to the emissions problem may seem small compared with emissions for transportation (the largest contributor), those places instituting gas hookup bans are only banning use of gas in new construction. In California, for example, 26 jurisdictions have passed laws to require “all-electric” construction, including Berkeley, Oakland, and San Francisco, though some exceptions to “all-electric” exist for commercial cooking.

“You build a new building and it’s there for 50, maybe 100 years,” says Mark Specht, a senior energy analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists. The idea behind the NYC ban and similar bans in California is simple, he adds. “If you put in the infrastructure for gas hookups, then you run the risk of locking in continued gas use for decades and decades down the road.”

Restaurant chefs mount some of the strongest objections to the gas bans, even though they will still be able to use gas in buildings where hookups already exist.

“If you want to start a restaurant that uses natural gas sources for cooking, there are lots and lots of buildings in New York City that can accommodate,” says Amy Turner, senior fellow at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School, “just not brand new buildings.”

Still, the model from the nation’s largest city could be “hugely influential” for other cities and states looking to enact similar legislation to slash emissions, Ms. Turner says. (And New York Gov. Kathy Hochul this month announced her support for a statewide gas ban.)

S&P Global Market Intelligence

“You just couldn’t have the menu that we have [without gas],” says Tony Palermo, co-owner of Tony P’s Dockside Grill in Marina Del Rey, California. A chef for more than 50 years, he likes the way the gas burners can sear a steak, cook it evenly, and provide reliable heat.

U.S. census data suggests that gas fuel for cooking is used in about 40% of American homes, and those most vocal about it suggest how powerfully a cultural tradition like cooking can come to bear on public policy. Many may see the larger picture of environmental responsibility of reducing emissions from natural gas used to heat buildings or to power electrical production, but some objections at the grassroots level boil down to the attachment to cooking over fire.

The taste for flame-kissed food is ancient

“Our tastes have been shaped through the generations by food cooked by direct flames,” Willow Mullins, professor of folklore and ethnology at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, explained in an email interview. “As a result, there’s a cultural distrust towards other ways of cooking in which we can’t see the fire, even if we know they work.”

One of those other ways, powered by electricity, is the precise but pricey induction range.

Ms. Mullins adds that even when those other forms of cooking are used, “we still go looking for signs of the kiss of flame, the char on meat, the crunch of bacon, the Maillard reaction. It’s so ingrained, that sous vide cooks will add it later with a kitchen torch.”

“It would just be a period of acclimating” for gas cooking aficionados because there are good gas-free electric ranges, suggests Nora Singley, a professional food stylist who splits her time between California and New York and prefers the controlled heat gas cooking offers.

For some amateur chefs, like Beth Beeman, a San Clemente, California, resident who doesn’t have a gas hookup, cooking on a gas stove is appealing. “Don’t get me wrong, I’m very supportive of environmentally sensitive and friendly actions,” she says. “From a cooking perspective, I would give my right arm to have a gas stove.”

“There’s certainly a lot of allure to gas stoves,” says Stephen Pantano, chief research officer at CLASP, a nongovernmental organization focused on the climate benefits of efficient appliances and an amateur chef himself, who cooks on electric. But, even beside the new laws, individuals, too, have a role to play.

“It needs to be more in the forefront of people’s awareness because it’s something much like the car where people have personal decisions to make that can really make a big difference over time,” he says.

S&P Global Market Intelligence

The Explainer

They shrink. They grow. The tricky politics of national monuments.

The designation of national monuments is more than partisan tug of war. Underneath the administrative back-and-forth lie questions about executive power, checks and balances, and enduring change.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

For more than a century, presidents have created national monuments to protect areas of historic, scientific, or cultural significance. But in December 2017, Republican President Donald Trump cut the size of three monuments originally established by Democratic Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama.

President Joe Biden restored the original boundaries of the monuments this fall. But Mr. Trump’s move raised a key question: If a president can designate a national monument, can a different president take it away?

Since the early 20th century, more than 100 national monuments have been created by both Republican and Democratic presidents through the Antiquities Act of 1906. But “there have been questions surrounding the act, particularly the size of national monuments ... pretty much from the beginning,” says Frank Pierce-McManamon, founding director of the Center for Digital Antiquity at Arizona State University.

Lawsuits arguing that Mr. Trump’s reversal was an unconstitutional expansion of executive power are still pending, and resolution will require either a court ruling or an update to the Antiquities Act by Congress.

The current ambiguity poses practical challenges, says Dr. Pierce-McManamon. When boundaries change every four years, it becomes difficult to manage the land effectively over the long haul.

They shrink. They grow. The tricky politics of national monuments.

For more than a century, presidents have created national monuments to protect areas of historic, scientific, or cultural significance. But in December 2017, to expand fishing and mining rights, Republican President Donald Trump cut the size of Bears Ears National Monument and two other national monuments: Grand Staircase-Escalante in southern Utah and Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine off Cape Cod.

The move raised a key question: If a president can designate a national monument, can a different president take it away?

Public land protections “must not become ... a pendulum that swings back and forth depending on who’s in public office,” said President Joe Biden in a speech this fall after restoring the original boundaries for the three monuments, originally established by Democratic Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama.

But the designation of national monuments in the United States is more than partisan tug of war. Underneath the administrative back and forth lie questions about executive power, stewardship, and trust.

How are national monuments created?

Unlike a national park, which is created through an act of Congress, national monuments can be created by the president alone through the Antiquities Act of 1906.

When the act was first established, people were concerned about the “looting and destruction of archaeological sites that was occurring,” says Frank Pierce-McManamon, founding director of the Center for Digital Antiquity at Arizona State University. Presidential power meant faster protection.

The act’s passage was bolstered by a shift in national thinking about the value of nature as more than a resource for extraction.

As the nation developed and urbanized, “the open spaces began to have a perceived greater value ... not just in board feet of timber ... but an aesthetic value that spoke to the need for open spaces,” says Sara Dant, author of “Losing Eden: An Environmental History of the American West.”

When did national monument designations become controversial?

Since the early 20th century, more than 100 national monuments have been created by both Republican and Democratic presidents. But “there have been questions surrounding the act, particularly the size of national monuments ... pretty much from the beginning,” says Dr. Pierce-McManamon.

National monuments are created on land owned and managed by the federal government. A national monument designation changes what is allowed on the land. Often, activities such as drilling, mining, and grazing are prohibited, but existing land rights are grandfathered in.

The use of the Antiquities Act so far in the 21st century has reignited old debates about how public land should be used: whether for natural resource extraction or for the preservation of diverse ecosystems, carbon-sequestering soils, and areas sacred to Native American tribes like Bears Ears.

The public lands debate is about not just land use but whether the president and the federal government at large are the appropriate caretakers.

“The lands are overseen by bureaucrats thousands of miles away in Washington, and the very people whose lives are most affected ... are denied any say in the process,” wrote members of Utah’s congressional delegation in an opinion piece after Mr. Biden reinstated the monuments’ original boundaries.

While some Americans trust that “the federal government has a positive stewardship role to play,” others “are more wary and less confident of a federal government that will do good for all the citizens,” says Dr. Dant.

What’s next?

Lawsuits arguing that Mr. Trump’s reversal was an unconstitutional expansion of executive power are still pending, and resolution will require either a court ruling or an update to the Antiquities Act by Congress.

The current ambiguity poses practical challenges, says Dr. Pierce-McManamon. When boundaries change every four years, it becomes difficult to manage the land effectively over the long haul.

Long-term resolution concerning how public lands should be used and who has the power to decide requires moving away from a zero-sum mentality, says Dr. Dant. “Finding that balance between the national and the local ... and caring then about these places that we all share, I think that’s really key.”

Kevin Day: Music transformed him. Now he aims to help others.

Creative expression is always linked to its source. The works of composer Kevin Day are infused with his experience with perseverance, and a desire to pass that strength along to listeners.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Composer Kevin Day is breaking racial and age barriers in classical music.

His work has already been performed at the Tanglewood Music Center in Lenox, Massachusetts, and Rachmaninov Concert Hall in Moscow. In April, he will conduct a new work at Carnegie Hall in New York. This Thursday, he will debut a piece commissioned by the Boston-based Sheffield Chamber Players.

To reach these pinnacles, the 20-something Black composer has had to overcome acute challenges, including a childhood speech impediment and the death of a close friend. “Music literally did heal me,” he says.

Mr. Day’s life story is a testament to the revivifying power of music. His ambition is to compose works that have a similar effect on listeners.

“I know what it is to have to persevere,” he says. “My goal is to try to help others as well.”

Kevin Day: Music transformed him. Now he aims to help others.

When Kevin Day was a child, he could barely speak due to a speech impediment. Yet he was prodigiously fluent in the language of music. His father, a hip-hop producer, and his mother, a gospel singer, noticed their toddler would hum melodies that he heard. They showed him how to articulate them on a piano.

“I couldn’t talk hardly until I was 8 or 9 years old,” says the native of Arlington, Texas, who had a stutter. “Music was sort of my way of self-expression when I couldn’t verbally communicate what I felt.”

Now in his mid-20s, Mr. Day is breaking racial and age barriers in classical music. His work has already been performed at the Tanglewood Music Center in Lenox, Massachusetts, and Rachmaninov Concert Hall in Moscow. In April, he will conduct a new work at Carnegie Hall in New York. And this Thursday, he will debut a piece for the Boston-based Sheffield Chamber Players. To reach these pinnacles, the young Black composer has had to overcome acute challenges. Mr. Day’s life story is a testament to the revivifying power of music. His ambition is to compose works that have a similar effect on listeners.

“He is driven, but he is so uplifted and soothed and buoyed by music that I don’t think it’s a choice for him,” says Cynthia Johnston Turner, dean of the music faculty at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario. During her previous post at the University of Georgia, she successfully recruited Mr. Day for a master’s program. “He has a lot of resilience, but let’s not ignore the fact that the systems are stacked up against him.”

Early influences

Mr. Day’s work is influenced by life experiences as much as by musical notes. When he was around 10 years old, his family’s struggles deepened. His father could not work because of a disability and his mother was unable to find a job. Sometimes there was no electricity or water in the house. As bills piled up, the family was evicted and had their car repossessed.

“I don’t make a big deal out of this stuff,” Mr. Day writes in an email after a Zoom interview. “I’m always looking forward and try not to look back, if only for reflection.”

Still, the young composer’s childhood memories often have a halcyon hue. Mr. Day cherished the opportunity to learn euphonium and tuba in marching band at school. His best friend from church, Davion Moulton, would help write beats for songs when they weren’t watching “Star Wars.” Mr. Moulton aspired to direct movies. Mr. Day dreamed of being a film composer. They seemed destined for future collaborations.

In 2015, Mr. Moulton was murdered in a shooting at a party. When the news reached Mr. Day – then a freshman at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth – he sank into a depressive state. It lasted for years. Though Mr. Day contemplated quitting music, he recalls the day in which he sequestered himself inside a piano practice room. His fingers began to improvise a melancholy minor chord motif. As the melody progressed, it brightened into something more hopeful.

“Something like spiritual, divine took place because, for the first time in a long time, I felt like someone might be watching over me and someone up there really cares,” says Mr. Day, who titled the composition “Breathe.” “That moment was a turning point. That piece was sort of my way of telling myself, ‘We’re going to be OK.’”

When he’d fully recovered about a year later, the composer’s friends pointed out something he hadn’t even noticed. He’d completely stopped stuttering. “Music literally did heal me,” he says. “It transformed me, in a way, to the person I am now.”

“Spirit of resilience”

On Jan. 27, Mr. Day will be in Massachusetts to attend the premiere of his String Quartet No. 5, which will be performed live in Waltham and streamed online. The Sheffield Chamber Players approached Mr. Day – as well as renowned composers such as Osvaldo Golijov and Kenji Bunch – to create new works for the group’s next few seasons.

Mr. Day says the two contrasting movements in String Quartet No. 5 represent the introspective and extroverted aspects of himself. “It’s a piece about where I’m now currently as a composer, where I am as a person, dealing with self-discovery, self-love, self-worth,” he says. Arranged for two violins, a viola, and a cello, the new work lends itself to simplicity and nuance, says the composer.

To date, Mr. Day’s 200-plus compositions include works for concert bands and chamber and symphony orchestras. He’s keen to branch into contemporary music, including hip-hop and jazz. He is also earning his doctorate in musical arts in composition at the University of Miami Frost School of Music.

His parents are proud of his achievements, he says, but adds with a laugh that they still remind him to take out the trash when he visits. “I have this sort of spirit of resilience that I’ve kind of inherited through them,” says Mr. Day.

It’s given him a sense of urgency to create music that bolsters listeners going through difficult times. “I know what it is to have to persevere. My goal is to try to help others as well.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why Italy can’t let Mario Draghi go

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Just 17 years ago, Italy was dubbed “the sick man of Europe.” Its economy was weak and its politics fractious. In 2020, it was the most affected country in Europe by the pandemic. By last September, however, The Economist magazine named Italy as “the country of the year.”

Since early 2021, Europe’s third-largest economy has enjoyed a broad governing coalition that is highly consensual. This has led to rapid economic growth – faster than any other in Europe. Deep reforms have begun to inspire more young people not to emigrate.

Much of the credit for this turnaround has been given to Mario Draghi, a U.S.-trained economist who was appointed prime minister last February when Italy faced a political crisis. Now Italians are debating if they can operate without him. On Monday, more than 1,000 elected leaders and special representatives began a series of votes to elect a new president.

More of a civil servant than a politician, he has now set a model for a stable party system in Italy. It is up to Italians to absorb what it takes to keep it that way.

Why Italy can’t let Mario Draghi go

Just 17 years ago, Italy was dubbed “the sick man of Europe.” Its economy was weak and its politics fractious. In 2020, it was the most affected country in Europe by the pandemic. By last September, however, The Economist magazine named Italy as “the country of the year.”

Since early 2021, Europe’s third-largest economy has enjoyed a broad governing coalition that is highly consensual. This has led to rapid economic growth – faster than any other in Europe. Deep reforms have begun to inspire more young people not to emigrate.

Much of the credit for this turnaround has been given to Mario Draghi, a U.S.-trained economist who was appointed prime minister last February when Italy faced a political crisis. Italians have welcomed his qualities of leadership as the country begins to receive $243 billion from the European Union in pandemic-related recovery aid. The EU itself holds great trust in him as he once led the eurozone’s central bank.

Mr. Draghi’s style is to listen to all sides, ask questions, and offer innovative solutions. He also largely keeps his political views to himself, encouraging others to find common ground. Perhaps most of all, he is respected for his humility.

“My personal destiny matters absolutely not at all,” Mr. Draghi said last month. “I don’t have particular aspirations of one type or another. I’m a man, a nonno [grandfather] if you like, at the service of institutions.”

Now Italians are debating if they can operate without him. On Monday, more than 1,000 elected leaders and special representatives began a series of votes to elect a new president. The position is largely ceremonial but has become increasingly influential. For many, Mr. Draghi is a perfect candidate to serve a seven-year presidential term. Yet others worry that politics will revert to dysfunction if he is no longer prime minister.

True to his style of trust-building, he is not worried. “We have created conditions so that work on the [reforms] can continue,” he said. “The government has created these conditions, independent of who will be [in command]. People are always important, but ... it’s also important that the government is supported by the majority” in Parliament.

Respect for Mr. Draghi began in 2012 when, as head of the eurozone’s central bank, he saved the faltering euro currency. He fulfilled a promise to do “whatever it takes” to stabilize financial markets. More of a civil servant than a politician, he has now set a model for a stable party system in Italy. It is up to Italians to absorb what it takes to keep it that way.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Reclaiming ‘if only’ moments

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Richard Gates

It’s never too late to open our hearts to the light of Christ, which redeems, reforms, and leads us forward in ways that bless.

Reclaiming ‘if only’ moments

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, writes, “It is good to talk with our past hours, and learn what report they bear, and how they might have reported more spiritual growth” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 330). Most of us have at times reflected on our past accomplishments and reevaluated our goals. Yet what if this journey of self-assessment includes “if only” moments?

What we now see as misguided actions or lost opportunities are not irredeemable. And while it may be impossible to relive the past, we can still amend our present thoughts about it through prayer. By aligning our thinking more accurately with God’s view of us as His beloved offspring and with what He truly knows of our history, we are able to yield to the redeeming action of divine Love, God.

This renewing influence can restore our sense of innocence and well-being. The Bible promises, “I will restore to you the years that the locust hath eaten” (Joel 2:25).

Christian Science teaches that God, divine Principle, is the only cause of all real being, and that everyone is His effect or witness, expressing His intelligent action. Accordingly, divine Principle or Love is not the source of careless decisions, wrongful actions, painful memories, or trauma. Recognizing this, we can prove mistakes powerless to prolong or even produce sorrow, futility, or defeat. Through prayer, former blunders can be rectified, punishing grief and regret can be overcome, and a recompense for irreparable loss can be realized.

For example, Saul of Tarsus, a notorious persecutor of the early Christians, is depicted in the Bible as “breathing out threatenings and slaughter against the disciples of the Lord” (see Acts 9:1-18). On his way to Damascus, Saul is rendered blind. Meanwhile, Ananias, a Christian disciple, is divinely directed to heal Saul of his blindness. Ananias recounts Saul’s unsavory reputation and questions his worthiness of healing.

Nonetheless, Ananias obeys the Christly mandate and heals Saul, who is then baptized and goes on to advocate for the teaching and practice of Christianity, fulfilling God’s intent for him. He later assumes the name Paul in evidence of his redeemed character.

In reality, the Christ – the pure manifestation of God’s love for mankind, which transformed Saul – has always been wisely guiding us. And even if we have strayed, divine Love patiently waits to bless us with spiritual enlightenment and redemption, liberating our way forward as we yield obedience to God’s law. On this pathway of reform, we begin to prove that wrongdoing and false character traits do not define our bygone years nor determine our potential for present and future progress and success.

To vacate the mortal narrative for the spiritual facts of being is not careless injustice or an imprudent ignoring of mistakes. It is an inevitable yielding to our own “high calling of God in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 3:14).

Accepting our true, unblemished spiritual record, we rejoice in the knowledge of God’s ever-present care. Then past regrets, lost opportunities, and fears for our future have no basis or authority to harm us. Bad memories do not accurately portray our actual, spiritual identity. So they must yield to the corrective action of Christ.

No condemning rehearsals of error or projections of continuing failure can withstand this purifying action of Christ, which eternally advocates for our spotless selfhood as the perfect image or expression of God. In God’s perfect creation and superior design, there is nothing to limit our potential, make us afraid, paralyze our growth, or render us vulnerable to recurring setbacks and loss.

Instead, we can reclaim “if only” moments, assured that only divine Love’s plan can be worked out in us. Increasingly, we will witness God’s will being fulfilled as we turn wholeheartedly to Him and obediently listen for, embrace, and follow His guidance and correction. Mrs. Eddy remarks: “We own no past, no future, we possess only now.... Faith in divine Love supplies the ever-present help and now, and gives the power to ‘act in the living present’ ” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 12).

In this “living present,” we can accept our innate spiritual selfhood as forever intact, never controlled or compromised by “if onlys.” As we humbly consent to divine Love’s healing action, we are absolved of the impulse to mourn the past or to carry forward its emotional wounds. Rather, we expunge “if onlys” and reinterpret them in accord with the consistency of the Science of being and its ever-present health, holiness, and harmony – our true record.

Adapted from an article published in the Jan. 17, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Let’s dance

A look ahead

Thanks for reading today’s stories. Do share your favorite pieces with others by clicking the share button on the top right corner of each story. And join us again tomorrow for a look at how empty churches are being repurposed into everything from skate parks to community centers.