- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Ukraine attack: Putin target may be democracy, near and far

- A public defender has never served on Supreme Court. Jackson would be first.

- Find safety or defend home? No easy choices in besieged Kyiv.

- ‘Freedom Convoy’ gone, but lanes of trust still blocked in Canada

- How two women found the courage to love their true voices

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Exploring the intersection of accent, identity, and respect

I was in the fifth grade. It was recess. A friend and I were playing by the jungle gym, and for whatever reason we were talking about kitchen appliances. I distinctly remember referring to the thing you use for baking as an “oh-ven,” rhymes with “woven.” My friend laughed and corrected me.

Apparently, it was pronounced “uh-ven,” like “lovin’.”

My friend hadn’t been cruel about it, but I was mortified. I took pride in my English, even at that age. I had this sense, unarticulated but powerful, that if only I could get my accent right, if only I could sound American enough, I would automatically belong in my new California town – never mind that I’d been raised in the Philippines.

In producing the Monitor’s new podcast, “Say That Again?” I’ve unearthed a bunch of memories like this: moments when I affixed a sense of self-worth to the way I spoke. They’re mostly small moments, but together they show how deeply I’ve tied my identity to how I talk.

That’s why my co-host, Jingnan Peng, and I started this podcast. We wanted to understand some of the ways that accents, languages, and voices influence how we see ourselves and one another. (Jing, who’s from China, has also thought a lot about this.) What we found were profoundly personal stories about people fighting prejudice, forging connections, and finding pride in their own voices.

These stories have made us think about what meaningful communication looks like in a diverse world. About times when we stopped hearing what someone had to say because we were so caught up in how they were saying it. And they reminded us that there’s so much to celebrate about all the ways we talk.

We hope you check out the podcast. You can find our weekly episodes at csmonitor.com/saythatagain.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Ukraine attack: Putin target may be democracy, near and far

It is a paradox of democracy that it can seem both weak and threatening at the same time. Whatever challenges democracy is facing, a Slavic version may have appeared undesirable on Russia’s border.

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

Vladimir Putin has professed many justifications for Russia’s assault on Ukraine, from wild claims about “de-Nazifying” the country to anger at Kyiv’s desire to join NATO, the Western treaty alliance.

It may also be a way for him to highlight the weakness of democratic systems – while ridding Moscow of an inconvenient neighbor.

Democracy poses a dire threat to Mr. Putin, after all. Ukraine’s democratic history is far from perfect, yet the existence of a functioning elected government on Russia’s border could make ordinary Russians whose electoral choices have been constrained in recent years wonder: If ballots work in Kyiv, could they not work again in Moscow, too?

Mr. Putin may also have seen problems in Western democracies as an opportunity. In the United States, electoral democracy is showing cracks as voters polarize and former President Donald Trump’s false claims of a stolen election spread through the Republican Party. In Western European states, far-right parties have gained ground in recent years, and white supremacist populist beliefs are on the rise.

Former Ukrainian Prime Minister Oleksiy Honcharuk said in December that for Mr. Putin and his cronies, “it’s very important that the Russian people believe that democracy is a weak idea and is a failing idea.”

Ukraine attack: Putin target may be democracy, near and far

In launching a brutal, unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, Russian leader Vladimir Putin is attacking not just a sovereign nation but the very idea of democracy – Ukraine’s, and America’s.

Democracy poses a dire threat to Mr. Putin, after all. Ukraine’s democratic history is far from perfect, yet the existence of a functioning elected government on Russia’s border, in a country that used to be a Soviet republic, could make ordinary Russians whose electoral choices have been constrained in recent years wonder: If ballots work in Kyiv, could they not work again in Moscow, too?

At the same time, Mr. Putin may have seen problems in Western democracies as an opportunity. In the United States, electoral democracy is showing cracks as voters polarize and former President Donald Trump’s false claims of a stolen election spread through the Republican Party. In France, Germany, and other Western European states, far-right parties have gained ground in recent years, and white supremacist populist beliefs are on the rise.

Put these perceptions together and a war of choice may seem like a solution. Mr. Putin has professed many justifications for Russia’s assault on Ukraine, from wild claims about ‘de-Nazifying’ the country to anger at Kyiv’s desire to join NATO, the Western treaty alliance. Another might be that Mr. Putin and other top Russian officials believe it’s a way to highlight the weaknesses of democratic systems and the vitality of an authoritarian axis of Russia and China – while ridding Moscow of an inconvenient neighbor.

“Putin himself has promoted an idea that the East has different values than the West, that they have different notions of democracy than the West, that his version of autocracy, along with [Chinese leader] Xi Jinping’s, is a cultural norm,” says Derek Mitchell, president of the National Democratic Institute.

Ukraine’s record

Ukraine’s government is clearly a central target of the Russian attack. At the time of writing, reports indicated that Russian troops had entered the capital of Kyiv from the north, and Ukrainians were bracing for a violent battle for the city. There were inconsistent reports of a Russian willingness to negotiate with Ukraine.

Russian officials have charged Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and his cabinet with being “militaristic,” “neo-Nazis,” and most of all, stooges for “American lies.” The Russian Foreign Ministry has said one of the aims in invading Ukraine is to “bring the current puppet regime to justice.”

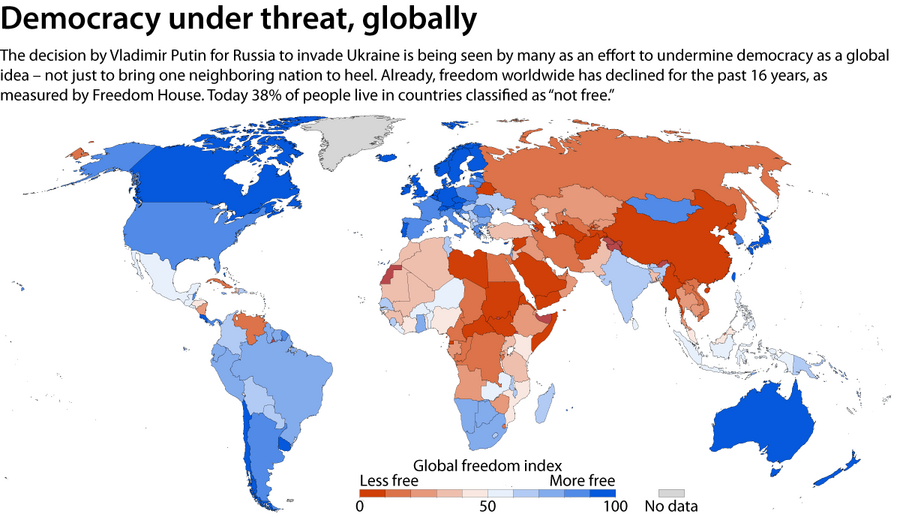

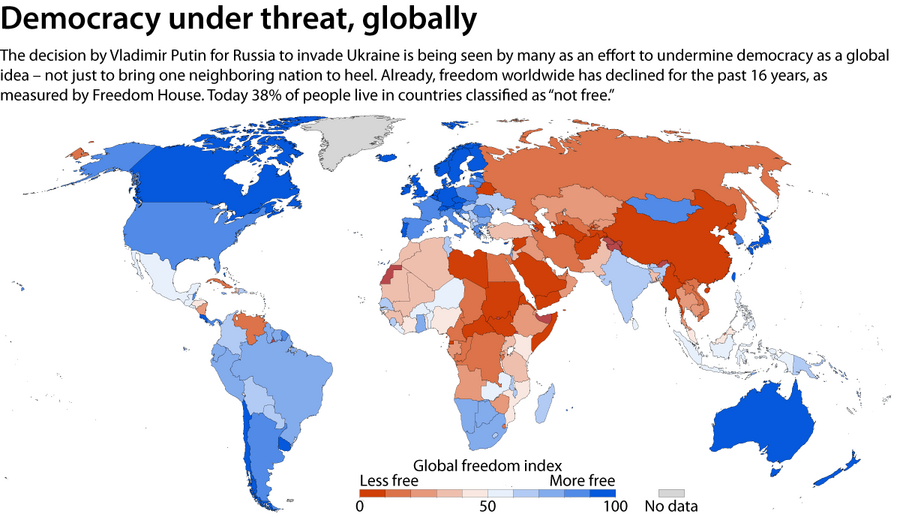

Freedom House

Ironically, when the Soviet Union crumbled in late 1991, American officials worried about the implications of Ukraine completely severing ties with Russia. Their economies were so intertwined that such a move could be “disastrous,” wrote National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft in a memo for President George H. W. Bush.

But events moved too fast to avoid that eventuality. Ukraine held a referendum on independence on Dec. 1, 1991, that passed overwhelmingly. At the end of that month, the Soviet Union officially dissolved.

For 30 years since, Ukraine – the largest country by land mass within Europe – has struggled to build a democracy. Its democratic institutions are not yet fully free and fair by Western standards, despite the ouster in 2014 of the Russian-leaning former president, Viktor Yanukovych, after widespread civic protests.

Corruption remains endemic, and efforts to combat it have met resistance, according to Freedom House, a nongovernmental organization that studies human rights and democracy around the world. Attacks against journalists and civic activists remain frequent.

But elections for president and legislative representatives have lately been almost entirely free. Freedom House gives Ukraine an overall “global freedom” rating of 61 on a scale of 100.

While Ukrainian democracy has had some problems, “we are still an electoral democracy with fair elections,” said former Ukrainian Prime Minister Oleksiy Honcharuk in an interview on the Stanford University “World Class” podcast last December with former U.S. Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul.

And for the Kremlin, it is dangerous to have even somewhat successful democracies close by, especially in Slavic, Orthodox Christian countries with close Russian ties, said Mr. Honcharuk.

For Mr. Putin and his cronies “it’s very important that the Russian people believe that democracy is a weak idea and is a failing idea, and that democracy doesn’t work for Russia ... or at least doesn’t work for the region,” Mr. Honcharuk said.

If Ukraine, as Mr. Putin says, is culturally Russian, then a pro-democracy Ukraine is indeed a threat to Russian autocracy, adds Mr. Mitchell of the National Democratic Institute.

“It’s very clear that he’s ... threatened by the unity and the democratic orientation of Ukraine,” he says.

Democratic backsliding

Mr. Putin may also have seen military action as a viable answer to his Ukraine problem due to the deterioration of democratic politics in the United States and other Western nations.

The rise of white supremacy groups, increased anti-immigrant sentiment, and the election of leaders who focus only on their own voting base have contributed to a growing expansion of “homegrown illiberal streaks” within democracies, concludes Freedom House’s Freedom in the World 2022 report.

Russia has long sought to widen these cracks in the West via such disinformation efforts as its meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Disunity at home could sap the will of the U.S. and its allies to act abroad in defense of democratic values, in the view of Kremlin leaders.

The conflict in Ukraine, regardless of what happens, is emblematic of the democratic backsliding that’s been occurring in nascent and established democracies – and of the strengthening of authoritarianism in Russia and China, says Pippa Norris, a professor of comparative politics at the Harvard Kennedy School who focuses on democracy, public opinion, and elections.

Competition between these forms of government moves in waves, Professor Norris says. Democracy rose before World War I and fell after with the rise of fascism. It rose after World War II and then fell again in the 1970s. It rose a third time with the fall of dictators in Greece, Portugal, Spain, and other countries.

“Now we’re seeing, essentially, the third reverse wave,” she says.

Given democracy’s troubles, the most notable thing about the response to Mr. Putin’s aggression against Ukraine may be how unified it has been so far. Professor Norris says it is especially surprising given the transatlantic divisions caused by former President Donald Trump, who harshly criticized the NATO alliance, and the reputational damage suffered by the U.S. after its chaotic pullout from Afghanistan under President Joe Biden.

“In this particular case, the amazing thing is how far Europe and America are falling into one voice and how they’ve all come together,” she says.

Eastern Europeans’ efforts

For more than a decade, Mr. Putin has carried out a salami strategy against Ukraine – carrying out his plan in small slices that individually haven’t merited a massive Western response. Russia has faced only limited consequences for such actions as its seizure of Crimea in 2014 and its continuing support of separatists in Ukraine’s Donbass region.

Limited consequences, until now. Since late last year, Western democracies have led an intense, coordinated diplomatic response to Russia’s build-up of troops around Ukraine, says Damon Wilson, president and CEO of the National Endowment for Democracy.

“This is just night and day between the reactions that Putin has faced in previous cycles, because we’ve learned if you don’t stop him, his appetite grows and he goes for more,” Mr. Wilson says.

Sanctions are only one part. The U.S. has also responded with troop deployments in Eastern Europe and the Baltic states intended to deter even further aggression.

Mr. Wilson says Putin’s aggression has in fact unified Ukraine, NATO, and even the U.S. itself. While there are some conservative voices questioning whether America should care about Ukraine and even praising Mr. Putin’s actions, the vast majority of both parties have denounced Russian aggression in no uncertain terms.

“There’s not really a big debate here,” says the National Endowment for Democracy president.

People in Eastern Europe are leading their own efforts to become democratic societies, he adds. They’re not being pressured or coerced by the U.S., the EU, or NATO.

“We can’t pull our punches or support for the aspirations of people who want a democratic future,” he says.

Freedom House

A public defender has never served on Supreme Court. Jackson would be first.

Most Americans know the words by heart: “You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford one, one will be provided.” The work of a public defender is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. Ketanji Brown Jackson could be the first Supreme Court justice to have served in that role.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

Harry Bruinius Staff writer

Ketanji Brown Jackson, a federal appeals court judge in Washington, made history Friday by becoming the first Black woman nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court.

If confirmed, she would replace Justice Stephen Breyer, whom she clerked for over 20 years ago. Justice Breyer has said he will retire when the court’s current term ends this summer.

Besides expanding the racial and gender diversity of the Supreme Court – she would become the fourth female member of the nine-person court, and its third person of color – she would also bring rare experiential diversity. She would be the first justice ever to have served as a public defender. The last justice with experience representing criminal defendants was Thurgood Marshall, the trailblazing former NAACP lawyer, who retired in 1991.

During her confirmation hearing for the D.C. Circuit last year, Judge Jackson said her service as federal public defender provided her with important insights when she became a trial judge. “There is a direct line from my defender service to what I do on the bench, and I think it’s beneficial.”

“Most of my clients didn’t really understand what had happened to them,” she continued. ”They had just been through the most consequential proceeding in their lives, and no one really explained to them what to expect.”

A public defender has never served on Supreme Court. Jackson would be first.

Ketanji Brown Jackson, a federal appeals court judge in Washington, D.C., made history today by becoming the first Black woman nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court.

If confirmed she would replace Justice Stephen Breyer, whom she clerked for over 20 years ago. Justice Breyer has said he will retire when the court’s current term ends this summer.

Besides expanding the racial and gender diversity of the Supreme Court – she would become the fourth female member of the nine-person court, and its third person of color – she would also bring rare experiential diversity. She would be the first justice ever to have served as a public defender. The last justice with experience representing criminal defendants was Thurgood Marshall, the trailblazing former NAACP lawyer, who retired in 1991. Judge Jackson would also follow in Justice Breyer’s footsteps as a justice who previously served on the U.S. Sentencing Commission.

“As a professional who has stood in the well of the courtroom, sat with individuals accused of crimes in jails and prisons, and understood the pain of the criminal legal system in communities across the United States, she can bring the voice of reality to a process that quite often suffers from abstraction and generalities, divorced from the realities of the street,” says Martín Sabelli, president of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

The U.S. Senate confirmed her nomination to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals in a narrow but bipartisan vote less than a year ago, and leading Republican senators today promised a respectful confirmation process. But they also suggested her nomination represents a victory for radical progressives.

It’s unlikely that she would change the ideological balance of the high court, where six justices have been appointed by Republican presidents. Of the last 19 Supreme Court appointees, she would be the fifth by a Democrat.

President Joe Biden announced Judge Jackson’s nomination at the White House this afternoon, fulfilling a campaign pledge to nominate a Black woman to the Supreme Court.

“For too long our government, our courts haven’t looked like America,” President Biden said. “And I believe it’s time that we have a court that reflects the full talent and greatness of our nation with a nominee of extraordinary qualifications, and that will inspire all young people to believe that they can one day serve their country at the highest level.”

“A real-world perspective”

Prior to serving on the D.C. Circuit, widely considered to be the second most powerful court in the country, Judge Jackson spent seven years as a U.S. district judge in Washington, D.C. Besides Justice Sonia Sotomayor, she would be the only Supreme Court justice with experience as a trial judge.

“You have to have voices from every part of the system in order for the system to be implemented and improved and balanced,” says Mr. Sabelli. “The law as it’s studied can be abstract, but the law as it’s practiced is real and has flesh-and-blood consequences every day.”

Born in Washington, Judge Jackson grew up in South Florida, raised by parents who were public school teachers and graduates of historically Black colleges and universities.

One of her earliest memories, she has said, is sitting with her father while he studied for his night classes at the University of Miami School of Law. When she graduated from high school, she was the first member of her family to attend Harvard University, where she later also got her law degree.

Besides “sterling credentials,” she has “a real-world perspective that comes from someone who wasn’t necessarily born into privilege,” says Melissa Murray, a professor at the New York University School of Law.

“She’s got the kind of résumé and experience that we equate with the American dream,” she adds.

Like many justices, Judge Jackson has a résumé that includes an Ivy League education, prestigious clerkships, and stints at big law firms. But it’s the less traditional paths her career took that reportedly caught the attention of President Biden: in particular, the two years she spent as a federal public defender.

During her confirmation hearing for the D.C. Circuit last year, Judge Jackson said that there is “a direct line from my defender service to what I do on the bench, and I think it’s beneficial.”

Representing clients who had already been convicted, she said she was “struck” by how little they knew about the legal process.

“Most of my clients didn’t really understand what had happened to them. They had just been through the most consequential proceeding in their lives, and no one really explained to them what to expect,” she told the Senate Judiciary Committee.

So “when I have to sentence someone – and I’ve sentenced more than 100 people – I always tell them ... this is why your behavior was so harmful to society,” she added. “This is why I, as the judge, believe that you have to serve these consequences for your behavior.”

Family history

Later in her career, Judge Jackson gained more nontraditional experience when she spent four years as vice chair of the U.S. Sentencing Commission, an independent, bipartisan agency that articulates sentencing guidelines for the federal courts.

Most notably, she was part of a unanimous vote to make retroactive new guidelines reducing the differences between federal sentences for crack and powder cocaine offenses. Noting that the harsher sentences were handed down mostly to Black and Latino men, she said, “No other federal sentencing provision is more closely identified with unwarranted disparity and perceived systemic unfairness.”

She was also connected to the issue in a personal way. Her father’s brother, an uncle she never really knew, was sentenced to life in prison for nonviolent drug crimes under a “three strikes” law in Florida.

In 2005, he sought her help after he learned she was a federal public defender, and she referred him to a law firm that handled clemency cases free of charge. Eleven years later, President Barack Obama commuted his sentence, along with more than 1,700 others convicted of nonviolent drug crimes. He died the year after he was released from prison.

In a speech Friday accepting the nomination, Judge Jackson acknowledged her uncle, but also emphasized that she has several family members who have worked in law enforcement – including her brother, who was a detective in Baltimore.

And she received an endorsement today from the president of the Fraternal Order of Police, Patrick Yoes.

While the FOP was “not always in total accord with her views” while she was on the Sentencing Commission, he said in a statement, “we are reassured that, should she be confirmed, she would approach her future cases with an open mind and treat issues related to law enforcement fairly and justly.”

Confirmation battle looms

While she has been confirmed by the U.S. Senate three times – including, most recently, last year in a 53-44 vote – the stakes of a lifetime appointment to the nation’s highest court will bring heightened publicity, scrutiny, and partisanship.

Both Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and Sen. Lindsey Graham, the ranking member of the Judiciary Committee, promised today that Judge Jackson will receive a respectful hearing. But Senator McConnell added in a statement that she “was the favored choice of far-left dark-money groups.” Senator Graham, who voted to confirm her to the D.C. Circuit last year, tweeted that “the radical Left has won” with her nomination, and that “the Harvard-Yale train to the Supreme Court continues unabated.”

Indeed, all but one current justice has a law degree from Harvard or Yale University: Amy Coney Barrett, who earned her degree from Notre Dame. But supporters say that’s a reductive view of Judge Jackson’s experiences and perspectives.

“It’s the only diversity [issue] they can lament,” says Professor Murray of New York University.

“It’s worthwhile to think about a more diverse educational profile of the justices,” she adds, “but I want to resist the idea that just because someone has been educated at Harvard or Yale they’re somehow out of touch with the American people.”

Out of 116 justices, Judge Jackson would become just the sixth woman, the fourth person of color, and the first with experience as a public defender. Only her former boss came to the court having served on the Sentencing Commission.

And while, if confirmed, Judge Jackson would join a Supreme Court replete with Ivy League connections, she would also join the ideological minority of a very conservative court. This term, the court appears poised to expand gun rights, restrict – or even overturn – the right to abortion, and reduce limitations on religious expression in public schools. Last year, the court ruled unanimously that the retroactivity Judge Jackson and the Sentencing Commission approved for crack offenders only applied in certain cases.

Speaking at the White House today, President Biden praised her as “a proven consensus-builder.” And Judge Jackson added that Justice Breyer – well known for trying to work with his conservative colleagues – had shown her that a justice “can perform at the highest level of skill and integrity while also being guided by civility, grace, pragmatism, and generosity of spirit.”

In addition to Justice Breyer, she also paid tribute to another famed jurist – Constance Baker Motley, the first Black woman appointed as a federal judge. They share a birthday, she noted.

“Today I proudly stand on Judge Motley’s shoulders,” she said, “sharing not only her birthday, but also her steadfast and courageous commitment to equal justice under law.”

If she’s confirmed, she added, “I can only hope that my life and career ... and my commitment to upholding the rule of law and the sacred principles upon which this great nation was founded will inspire future generations of Americans.”

Find safety or defend home? No easy choices in besieged Kyiv.

With the battle between Russian and Ukrainian troops creeping closer, residents of Kyiv face a dilemma: flee with what they can to safer territory or risk the danger in their homes.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

As Ukraine’s commercial airspace closed with fighting intensifying, hundreds of thousands of Kyiv residents escaped the capital. The mass departure transformed the city on Friday from a vibrant, noisy, traffic-snarled metropolis into a desolate cityscape of empty buildings and deserted streets.

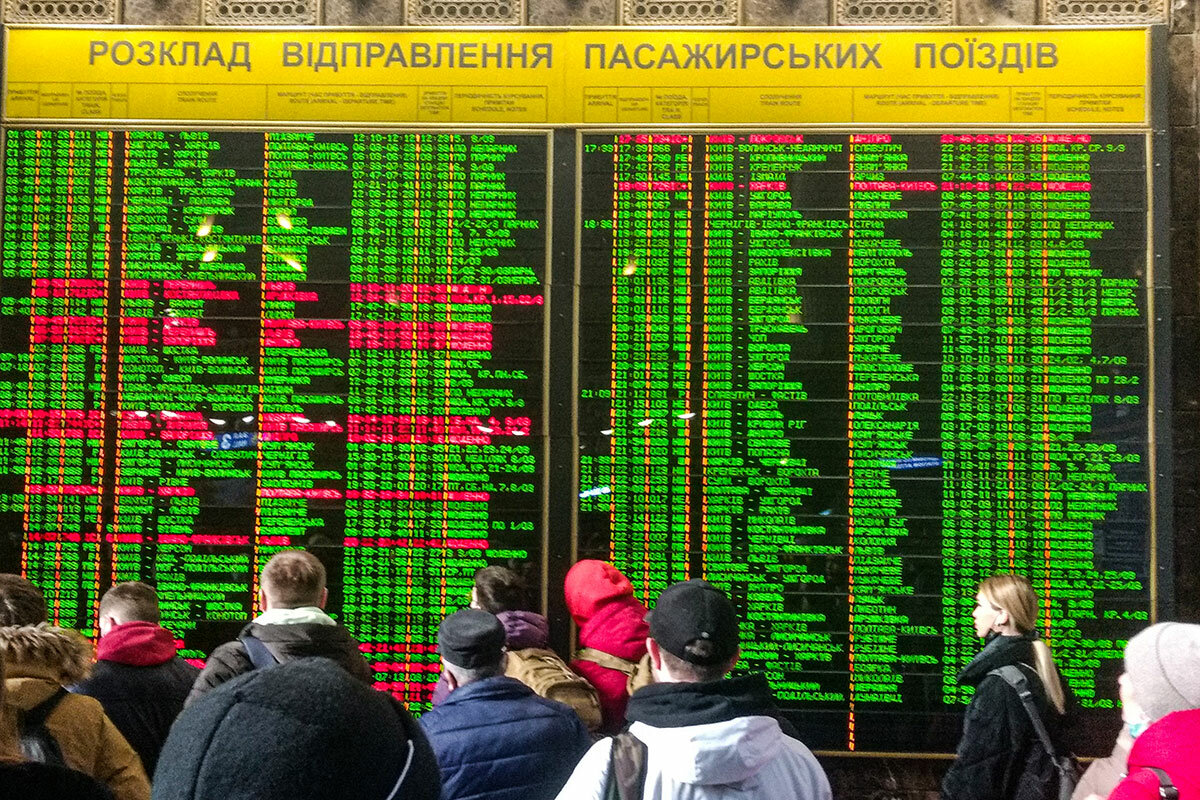

Couples and families sprawled on the ground or sat on luggage as throngs of people eddied through the main railway station pulling suitcases and walking bowed under oversize backpacks. Others crowded beneath electronic schedule boards as they scanned for updates on delayed trains, necks craned heavenward.

“We don’t want to leave,” says Lilya Hnatkivskyi, who is fleeing Kyiv with her family. “But this is reality, and you have to be sensible. Ukraine is under siege by a brutal dictator.”

The decision of some residents to stay rather than seek refuge in the country’s quieter western region could appear a dangerous sort of magical thinking from the outside. But with night drawing near Friday, their reasons for remaining sound grounded in the gravity of the moment.

“This is about a country’s independence,” says Dzianis Haurylavets, who moved to Kyiv five years ago from Belarus. “We cannot abandon our nation or our principles.”

Find safety or defend home? No easy choices in besieged Kyiv.

An air-raid siren’s distant howl filtered through the main railway station in the Ukraine capital Friday as Arsen and Lilya Hnatkivskyi waited with their two children for an afternoon train. The invasion of Russian forces that began earlier this week had reached the outskirts of the country’s largest city by morning as many of its 3 million residents continued to flee in a tense exodus.

The Hnatkivskyi family’s poise diverged from the general mood in Kyiv, where sporadic explosions during the past 48 hours cracked the sense of calm that had prevailed in recent days even as the threat of war loomed.

Couples and families sprawled on the ground or sat on luggage as throngs of people eddied through the terminal pulling suitcases and walking bowed under oversized backpacks. Others crowded beneath electronic schedule boards as they scanned for updates on delayed trains, necks craned heavenward.

“Panicking won’t help anything. We just have to be ready to go,” Mr. Hnatkivskyi says. A video game developer, he moved with his wife and children to Kyiv five years ago from Ternopil in western Ukraine, and the family planned to return there provided their train arrived on time – and in time.

After weeks of tracking the news, the couple bought tickets Sunday evening, a night before Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered troops over the border. “We paid attention and planned because we knew this was possible,” Mrs. Hnatkivskyi says. They packed five suitcases of clothes, electronic devices, and mementos, and a face mask dangled from the neck of each family member, more out of concern with COVID-19 than a gas attack.

“We don’t want to leave,” she says. “But this is reality, and you have to be sensible. Ukraine is under siege by a brutal dictator.”

Russia’s multiprong invasion from the south, east, and north continued to unfold Friday with stunning breadth and swiftness across Ukraine, a country of 44 million people that declared its independence in 1991 after the fall of the Soviet Union. Defense officials in Kyiv reported Thursday more than 130 Ukrainian troops and 50 civilians killed. Casualty numbers for Russian troops remained unconfirmed.

Hundreds of thousands of Kyiv residents escaped by car, bus, and train with the country's commercial airspace closed and fighting intensifying. The mass departure had transformed the capital by Friday from a vibrant, noisy, traffic-snarled metropolis into a desolate cityscape of empty buildings and deserted streets.

Darkness cloaked the interiors of most shops, restaurants, and office buildings, and plywood, blankets, and garbage bags hung inside windows to guard against shattered glass. Long lines formed outside pharmacies and in front of the rare ATM here and there still dispensing hryvnia.

“Actually, I’m finding it kind of peaceful,” says Natasha Petrovna, walking back home from a grocery market with her boyfriend. He carries a plastic bag bulging with bread, cheese, water, and other provisions.

“We are still hoping for something good. Ukrainians are a strong people,” she says. Her boyfriend nods. “Ukrainian soldiers – very strong!” he says.

The decision of some residents to stay rather than seek refuge in the country’s quieter western region or abroad could appear from the outside as a dangerous sort of magical thinking. But with night drawing near Friday and people taking cover in underground parking garages, subway stations, and basements in case of an air attack, their reasons for remaining here sound grounded in the gravity of the moment.

“This is about a country’s independence,” says Dzianis Haurylavets, who moved to Kyiv five years ago from Belarus, where he grew weary of the autocratic rule of President Alexander Lukashenko. Russian troops stationed in Belarus have poured into Ukraine toward Kyiv. “We cannot abandon our nation or our principles.”

A dual devotion to family and country will keep Olga Andriyash in the city. The independent landlord intends to look after her elderly mother and lend moral support to her besieged homeland. “This is not only a threat to our territory but to our freedom, our basic humanity,” she says. “I see it as my duty and mission to our people, to our Ukraine.”

For Volodymyr Baranchuk, a retired shopkeeper, staying in Kyiv represents an expression of hope in Ukraine’s dark hour. “Nothing has changed here – except Russia,” he says with a smile.

Mr. Baranchuk had come to the train station Friday out of boredom rather than any impulse to leave. He explains that a hand injury from long ago prevents him from joining the country’s volunteer defense force that has mobilized to aid the military.

“But I will fight the Russians if they find me,” he says. “I’m not going anywhere.”

A deeper look

‘Freedom Convoy’ gone, but lanes of trust still blocked in Canada

How do Canadians rebuild trust in government – and respect for each other – following the “Freedom Convoy” blockade? Understanding the protest’s root causes could be a starting point.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Friday marks one month since hundreds of trucks first drove into the capital of Canada and catalyzed a far bigger movement than authorities or the public expected.

Though organized after Prime Minister Justin Trudeau upheld a vaccine mandate for truckers to cross the border from the United States, the movement quickly morphed into a protest against all public health restrictions and Mr. Trudeau himself.

The “Freedom Convoy,” as it was called, has since been cleared, but deep scars remain. The movement and all of the misunderstandings and misinformation around it have torn at the fabric of Canadian society and left the country grappling with how to restore trust that’s been lost on all sides.

On the one hand, some of the protest’s supporters saw public health mandates as government overreach. On the other, many living nearby who contended with blaring horns day and night found the government unable – or unwilling – to protect them.

“There’s a big ‘aha’ moment going on in Canada,” says Frank Graves, head of Ekos Research Associates, a polling group in Ottawa, Ontario. “This is not a hiccup,” he says. “This is not just a debate about vaccine mandates. This is something much deeper, more structural and challenging.”

‘Freedom Convoy’ gone, but lanes of trust still blocked in Canada

For René de Vries, it was peaceful and party-like. He made pancakes on one of the days he visited with members of the “Freedom Convoy” as it occupied downtown Ottawa in protest of Canada’s public health restrictions. “I thought it was great,” he says.

So when the convoy was condemned as a radicalized minority and cleared out with emergency powers by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, it reconfirmed his mistrust in mainstream media and mainstream politics. He says we’ve all been “bamboozled.”

For Zexi Li, an Ottawa resident whose apartment looks over the downtown core, where rigs and heavy trucks parked for three weeks, the past month has been oppressive. She barely slept, and only with the help of speakers and ear plugs, amid incessant honking of air and train horns.

“We didn’t see any steps taken by our leadership to help us when we so desperately needed it,” she says. So she agreed to be the lead plaintiff in a class action against the convoy.

Friday marks one month since hundreds of trucks first drove into the capital of Canada and catalyzed a far bigger movement than authorities or the public expected. Four chaotic weeks later, the convoy itself has been cleared, but deep scars remain. Those are both physical – as police continue to block roads leading to a fenced secure zone around Parliament Hill – and figurative. The Freedom Convoy – the movement itself and all of the misunderstandings and misinformation around it, especially as it became an international lightning rod – has torn at the fabric of Canadian society and left the country grappling with how to restore trust that’s been lost on all sides.

“There’s a big ‘aha’ moment going on in Canada,” says Frank Graves, head of Ekos Research Associates in Ottawa which has measured Canadian attitudes toward the Freedom Convoy. “This is not a hiccup. This is not just a debate about vaccine mandates. This is something much deeper, more structural and challenging.”

Mislabeled as extremists?

The convoy set out after the Liberal Prime Minister Justin Trudeau upheld a vaccine mandate for truckers to cross the border from the United States. (The same rule applied on the U.S. side.) But it quickly morphed into a protest against all public health restrictions and Mr. Trudeau himself.

But their tactics and alliances – amid growing international attention and funding, especially from the U.S., where vaccine skepticism is much higher – quickly came under the microscope. Among the biggest concerns were the radicalized positions of some of the organizers. Canada Unity, for example, issued a memorandum, since revoked, demanding the immediate end of all COVID restrictions. Hate symbols, though not identified with a particular group, were also reported on the scene of the protest.

Those who see public health measures as government overreach resent being cast as extremists. Mr. de Vries, who is not vaccinated, says he has always been into alternative medicine. So last April he began attending anti-lockdown protests, where he met other “like-minded” Canadians, he says. A man who once put his support behind the Liberal party has now run for office for the People’s Party of Canada, a right-wing, populist party that has attracted vaccine skeptics.

“I’m not an extremist guy,” he says via Zoom, while on vacation. “I”m a very middle-of-the-road person. … But especially in the last two years, there has been no dissent possible about lockdown measures or against Big Pharma.”

Mr. de Vries says his Twitter account was suspended during the convoy – he doesn’t know why. He says it’s possible some of the hate symbols – from a Confederate flag to a swastika that appeared in Ottawa – were “false flags” planted by the Trudeau government. But even if they weren’t, a few radical voices shouldn’t overshadow the entire movement, he adds.

“Any dissent, even when it’s peaceful, is presented as extremist, far right,” Mr. de Vries says.

Deserted by leaders?

For as much as Mr. de Vries feels misrepresented, Ms. Li is frustrated, she says, by the characterization of the convoy as a “peaceful protest,” and by criticism from outside that “this is just honking, live with it.” The trucks blared horns for hours every day, producing noise up to 150 decibels, her lawsuit states, a noise she says still rings in her ears even though the trucks are gone.

“Those ‘moderate people,’ those people that say they don’t want to torture you, they stand next to the people that do,” she says.

Ms. Li, a 21-year-old public servant, says she attempted to communicate with the convoy members parked on either side of her apartment block, trying to express the harm they were doing to her community. But she says they only retorted that they had been suffering for two years.

“People are frustrated with the pandemic. And yeah, we hear those cries of frustration, but ultimately, it’s about the way that they chose to express it and the harm they chose to do to other people,” she says. “Your home is supposed to be your sanctuary. It is supposed to be your safe space. But they took that away from us.”

Ms. Li says she agreed to be the face of the now $300 million class-action lawsuit after she watched police allow the protest to persist while politicians blamed one another instead of making the hard decisions. “I believed in the police. I believed in our government,” she says. “But the trust that they will make the right decisions for the public is gone.”

For her, rebuilding it can only come after a thorough investigation into what happened – why authorities allowed the protest to embed itself in the capital, a move that cost police chief Peter Sloly his job.

The long road to rebuilding trust

But Mr. Sloly’s actions are not the only ones to be examined. At its crisis point last week, Mr. Trudeau invoked the never-before-used Emergencies Act. It endowed the executive more authority, including freezing of accounts without a court order for those accused of supporting the blockades. For those already distrustful of the government, the invocation sealed their opinions that Mr. Trudeau is anti-democratic. Freedom Convoy organizers penned an open letter to Parliament asking if “Canadian democracy can survive such an incredible abuse of power.”

The use of the act is controversial well beyond the convoy itself – part of the reason Mr. Trudeau rescinded it Wednesday, just days after the House of Commons approved it. Another key to rebuilding trust will be how a public inquiry into use of the Emergencies Act plays out, says Abby Deshman, director of criminal justice for the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, which had opposed the act’s use.

“Are those actually going to be robust truth-seeking mechanisms? I think if they are, that will go a long way to restoring any trust that has been lost,” she says. “If, however, they turn out to be very superficial or extremely partisan exercises, I think that could be very damaging to the public’s trust.”

On the one hand, moving forward requires understanding some of the driving issues behind the protest. Mr. Trudeau has been criticized for labeling the group a “fringe minority” with “unacceptable views.” But roughly a third of Canadians said they sympathize with the protest and its objectives in a polling tracker by Ekos Research. Mr. Graves says that is a reflection of a growing “northern populism” that political elites have discounted and that has grown with the pandemic. This is a “distinct” group, he says, leaning rural, conservative, and working class. They are also overrepresented strongly in under-50 Canada.

“I think Justin Trudeau has done a number of things right during the pandemic. But the kind of dismissal of this as a really unpleasant fringe, it was sort of his Hillary ‘deplorable’ moment,” Mr. Graves says. “I think that is one of the common features, not just [in] the United States and Canada but throughout the advanced Western world, the tendency to diminish the significance of the problems the people who are attracted to these kinds of populist movements are experiencing.”

A vocal minority or a majority?

On the other hand, the protest was not just composed of Canadians tired of strict pandemic public health measures, though it garnered significant international attention at a time when global fatigue with the pandemic is widespread.

Amy Kaler, a sociologist from the University of Alberta who has studied protest movements, suspects American outlets in particular were drawn to the symbolism of rigs driving cross-country – “these kind of rugged individualists standing up to effeminate socialist Justin Trudeau who they really seem to hate,” she says. “I think what we are witnessing in real time is the crafting of an origin story.”

But in the shrill coverage, all sorts of distortions were made, starting with the labeling of this as a “trucker convoy.” Is it a trucker convoy when the Canadian Trucking Alliance condemned it, and the vast majority of Canadian truckers are vaccinated?

Is it a peaceful protest if it costs billions in international trade due to blockades at the border and in lost wages? Many Ottawa businesses had to shut down (including an entire downtown mall).

France, for example, is a country known for its boisterous striking, but there, protesters strike a balance between stating their message and maintaining approval. “The people on strike will pull back rather than persist to the point where they lose public support,” Dr. Kaler says.

Or perhaps swaying Canadians to their side was never the goal, she adds.

Many Canadians continue to maintain that at the core of this movement is a radical element promulgating misinformation and hate that appeals to more Canadians than the country has ever realized. Amanda Jetté Knox, an author in Ottawa, studies hate movements as part of her work in LGBTQ advocacy. Even she was surprised by the scale of it. She weighed in on the subject via social media, and received more personal attacks than ever; so has Ms. Li, who says she has received threatening calls and emails accusing her of being a mole for the Chinese Communist Party.

“I have lost trust in Canada being somehow safer than other places,” Mx. Jetté Knox says. “This is a huge wake-up call for Canada, and there’s a reckoning that needs to happen now.”

At the same time, Dr. Kaler says it’s imperative not to overplay divisions. Other moments in Canada’s history – from the hanging of Metis leader Louis Riel in 1885 to conscription during World War I – have been far more divisive with much higher stakes. This debate is not split down the middle. About a week before the protest was cleared, a poll by the firm Maru showed two-thirds (64%) of Canadians saying “Canada’s democracy is being threatened by a group of protesters and they must be stopped immediately.”

“There is a discourse that says we are deeply divided. But there is nothing really that supports that,” Dr. Kaler says. There is a very loud, angry group, she adds. “But that’s nowhere close to there being some great line dividing down the middle and people separating off.”

Listen

How two women found the courage to love their true voices

Embracing the way we speak means learning to accept ourselves – our pasts, our peculiarities, our pain. Two women show us what it takes to go down that road. Episode 1 of our new podcast series, “Say That Again?”

When a colleague told actor Cynthia Santos DeCure that she didn’t sound Puerto Rican enough to play a character from there, she was stunned. The island was her home, even though she’d spent much of her life trying to fit into the Los Angeles community she moved to when she was 14. She never really thought she could change so much that she would lose that crucial link.

“It was emotional,” Ms. Santos DeCure says. “I realized I had spent so much time perfecting other sounds, and not enough time really cultivating my own.”

Across the country, Amy Mihyang Ginther was also struggling to find her voice: to reconcile her experiences in the mostly white community in which she was raised with her longing to – literally – understand the Korean family who gave her up for adoption.

“‘[The] Little Mermaid’ was one of my favorite Disney movies growing up,” she says. “I could really relate to a character who was living in one world but had a yearning for another.”

Each woman’s story is a journey to learn what it takes to truly love every part of ourselves, and the role our voices play in the process. – Jessica Mendoza and Jingnan Peng, multimedia reporters/producers

This story was designed to be heard, but we understand that listening is not an option for everyone. For a full transcript of this episode, click here. Also: This podcast has a newsletter! It’s run by Jessica Mendoza and funded by the International Center For Journalists. Click here to subscribe.

Episode 1: You Are How You Sound

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Freedom from fear flares again in Tunisia

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Eleven years after Tunisia sparked the Arab Spring, its democracy seems doused by a dictator. Kais Saied, elected as president in 2019, has suspended parliament, granted himself almost total power, and put his main opponents under house arrest. Most importantly, he dissolved a constitutional body designed to preserve judicial independence.

Yet curiously, Mr. Saied said Feb. 24, “We have no intention – but rather we refuse – to interfere in the judiciary.” Faced with a refusal by many Tunisians to be intimidated by his power grab, the president appeared at least momentarily to blink. As he spoke yesterday, hundreds of judges and lawyers protested in Tunis along with a broad array of the general public.

“Tunisians tore down the wall of fear [in 2011] and they no longer feel intimidated by any form of repression ripped from the pages of the old regime’s authoritarian playbook,” says Noureddine Jebnoun, a political scientist at Georgetown University.

Confronted by an attempt to roll back the rule of law, Tunisians are showing that when a society is freed from fear and embraces democratic ideals, reversing that progress is difficult. The spark of the Arab Spring has not lost its brilliance.

Freedom from fear flares again in Tunisia

Eleven years after Tunisia sparked the Arab Spring democratic uprising, its own democracy seems doused by a dictator. Kais Saied, a legal scholar elected as president in 2019, has suspended parliament, granted himself almost total power, and put his main opponents under house arrest. Most importantly, he dissolved a constitutional body of peer-elected judges, lawyers, and legal experts designed to preserve judicial independence.

Justice, he said, is “not a branch of government.”

Amnesty International calls the dismantling of the High Judicial Council “the death knell for judicial independence.” Yet curiously, Mr. Saied said Feb. 24, “We have no intention – but rather we refuse – to interfere in the judiciary. Once again, power is for the people.” Faced with a refusal by many Tunisians to be intimidated by his power grab, the president appeared at least momentarily to blink.

As he spoke yesterday, hundreds of judges and lawyers gathered in Tunis along with a broad array of the general public. They chanted “Freedom! Freedom! The police state is finished” and waved placards. They declared that the dissolution of the judicial council is the destruction of the rule of law.

“Tunisians tore down the wall of fear [in 2011] and they no longer feel intimidated by any form of repression ripped from the pages of the old regime’s authoritarian playbook,” says Noureddine Jebnoun, a political scientist at Georgetown University’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies. “Notwithstanding democratic reversal, they have already put an end to the disastrous pattern of ‘presidents for life’.”

Since the toppling of the 23-year dictatorship of the late Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali in 2011, Tunisians have consolidated a culture of democracy with successive local and national elections. They approved a new constitution and held a national dialogue about atrocities under the past regime through a Truth and Dignity Commission. In 2015 civil society leaders known as the national quartet won the Nobel Peace Prize for shepherding a consolidation of constitutional reforms.

Those gains may be more durable than the moves by Mr. Saied to roll back democracy. His attempts to consolidate power face strong resistance from frequent and often large protests. Not even police water cannons have deterred protesters in recent weeks.

Confronted by an attempt to roll back the rule of law, Tunisians are showing that when a society is freed from fear and embraces democratic ideals, reversing that progress is difficult. The spark of the Arab Spring has not lost its brilliance.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘God with us’ all

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Jeannie Ferber

Wherever we are, whatever we face, God’s goodness is supreme. This spiritual reality offers a powerful basis for our prayers for peace and justice in the world.

‘God with us’ all

That we pray about challenges, including war, truly matters.

A powerful story of a war between two nations being halted holds compelling lessons for these times. In this story, from the Bible’s book of Second Kings, we are shown that everyone – both oppressors and oppressed – was surrounded by God’s “horses and chariots of fire” (see 6:8-23). This spiritual revelation, made known by the prophet Elisha, was an assurance of deliverance for all, because he had seen this very means bring deliverance before (see II Kings 2:12).

Deliverance, through acknowledging life in and of God, was no more powerfully demonstrated than by Christ Jesus. His undeviating recognition that all real being is found in God, included the corollary fact that whatever is unlike God’s infinite goodness could not actually be the reality it claims to be. Jesus proved God’s control under the severest of circumstances, dispelling any notion that some situation could halt the supremacy of God, divine Love. His understanding of God destroyed error, the belief that Love does not hold control. He saw this error not as a reality, but as a deception wrongly believed.

Countless people have proved these spiritual concepts as well – both modestly and in more dramatic ways – including the discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy. She wrote, “No evidence before the material senses can close my eyes to the scientific proof that God, good, is supreme” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 277).

A change in thought from fear to holy inspiration reveals any material picture not to have been the substance it claimed to be. But without boldly, spiritually confronting the mesmerism of war, it would claim to successfully deceive us. So we insist that our thinking not be invaded by any sense of helplessness, futility, or defeat. This kind of warfare – mentally destroying every claim that dares to oppose the knowledge and allness of God – is the only means of overcoming conflict and war.

That this approach is effective has already been proved. Our need, then, is to utilize this mightiest of means to save all.

If the worldwide challenges confronting us today loom large, that need not stop us from thinking clearly, fearlessly, spiritually, in the face of them. This was borne out in the experience of a young friend of mine. He lives in a country that was invaded by a neighboring country a few years ago. There were periods when, for weeks on end, the reprieve from the bombing was no more than three or four hours. During the day my friend read all the books he could, seeking answers to life’s meaning. When darkness fell, he filled the time thinking deeply about the ideas he’d been reading.

After weeks of such living, he managed to send an email off to me in which he wrote, “If you have faith, can you at the same time shake with fear at this madness? I mean that I must literally trust myself to God. I do not presume to convince anyone of this. But with this thought I’ve begun to live.”

The destruction all around my friend was so extreme that a mortal, material sense of life began to lose its meaning. As must always be the case, the greater any discord seems to become, rather than actually becoming more real, it begins to lose its legitimacy. In the midst of all the destruction, when my friend felt an irrepressible sense of life, he knew that what he was feeling could only be of God.

When a ceasefire was finally declared, my friend went the very next day to the public library, where he worked, to help clean up the debris. In less than an hour people came in not only to help, but to check out books!

In all ages, people have experienced the certainty that nothing could separate them from God, Love, Life. And because they couldn’t be kept from feeling God’s presence, they began to accept the inability of evil to control their lives.

In my experience with friends living in war zones, numerous times I’ve been turned away from a sense of hopelessness to the certainty of God’s control over all. That turning was nothing I could muster. It was Christ, the heaven-sent message of truth and love, assuring me of Love’s presence and power. Not surprisingly, these friends later have told me of unexpected supply, safety, new opportunity, and even times of joy.

It is comforting to know that we are turned to feel our oneness with God. We don’t turn ourselves, but are lifted up by the ever-presence of Love’s saving power. Like the biblical prophets, we can know God’s deliverance for all. God is the same here and now, wherever we are, whatever we face. “God with us” all, is the only God there is.

Adapted from an article published on sentinel.christianscience.com, Feb. 24, 2022.

A message of love

Fleeing war

A look ahead

Thanks for reading. Come back next week. We’re working on a raft of stories about the invasion of Ukraine, including on the West’s search for leverage against Russia, the role of China, and efforts to keep the conflict from spreading into NATO countries. You can find more of our coverage pulled together here.