- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

When telling means showing

Most Monitor storytelling is done with the written word. That’s just how we’re built.

Our small multimedia arm, charged mostly with audio, also happens to include a gifted videographer. When Jingnan Peng pitched a writing trip to Kentucky, he packed a video camera along with his notepad.

Today, he presents a rich story in two ways.

You might recall Jing’s lovely recent short on Miyawaki forests. (He spoke about his process on our weekly podcast.) This time Jing pairs a reported story on the rejuvenated legacy of a historically Black library in Louisville with a companion video that really brings us inside that library’s budding community.

It adds a dimension we think you’ll enjoy.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In China, Blinken offers warnings and praise

The United States and China are working hard to repair one of the world’s most consequential relationships. The U.S. secretary of state’s latest visit to Beijing highlighted progress made since last year, and moved the needle forward on key issues.

The last time U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited China’s capital, Beijing and Washington were barely on speaking terms. Now, 10 months later, both countries are rolling up their sleeves and digging into some major, divisive issues.

The United States and China have made important headway in areas ranging from counternarcotics to military communications, Mr. Blinken said at a Friday press conference concluding three days of high-level meetings in Beijing and Shanghai.

Still, China and the U.S. have vast differences, and China’s export of subsidized, surplus goods in key industries remains a challenge. The U.S. and other powers argue that China is distorting the global market, while China opposes what it sees as curbs on its economic rise.

With U.S. President Joe Biden facing the November election and Chinese leader Xi Jinping seeking to revive China’s sluggish economy, such frictions are unlikely to be resolved easily, experts say. Yet these domestic political priorities are also reasons both countries seek to maintain stability.

When discussing surplus exports, Mr. Xi told Mr. Blinken that Washington’s effort to contain China’s development “is a fundamental issue that must be addressed ... in order for the China-U.S. relationship to truly stabilize, improve, and move forward.”

In China, Blinken offers warnings and praise

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken urged China on Friday to curb the flow to Russia of Chinese dual-use equipment critical to Moscow’s war efforts in Ukraine – or face fresh sanctions.

“Russia would struggle to sustain its assault on Ukraine without China’s support,” Mr. Blinken said at a press conference following his meetings with Chinese leader Xi Jinping, Foreign Minister Wang Yi, and other top officials. China is Russia’s top supplier of machine tools, microelectronics, and nitrocellulose – a highly flammable compound used to make munitions – and Mr. Blinken noted that the U.S. has already sanctioned more than 100 Chinese enterprises. “I made it clear that if China does not address this problem, we will,” he said.

Mr. Blinken’s three days of high-level meetings in Beijing and Shanghai underscored how the United States and China are rolling up their sleeves and digging into some major, divisive issues. The last time Mr. Blinken visited China’s capital – 10 months ago – Beijing and Washington were barely on speaking terms, with military-to-military dialogues and other vital contacts suspended.

U.S. President Joe Biden and Mr. Xi stabilized the relationship and reopened more than 20 key lines of communication when they met outside San Francisco last November – unleashing new progress but also tough talks over pressing conflicts.

The two sides have since made important headway in key areas ranging from counternarcotics to multilevel military communications and talks on artificial intelligence, Mr. Blinken said. He highlighted China’s recent actions to curtail the flow to the U.S. of precursor chemicals used to make the drug fentanyl, which has become a leading cause of death among American adults. China has cracked down on some companies, and is providing information to help international law enforcement track and intercept the drugs, he said.

Mr. Blinken announced that Beijing and Washington reached an agreement Friday to hold their first talks on managing the risks of advanced AI, and military talks have resumed.

Yet China and the U.S. have vast differences, starting at the top with how each side characterizes the relationship. Washington believes the two countries can compete and cooperate at the same time. For Beijing, Washington can be either a partner or a rival – but not both.

China’s development rights

China’s top priority for Mr. Blinken’s visit was to “establish a correct understanding” of their current relationship status, according to a senior Foreign Ministry official quoted in a statement.

Mr. Xi emphasized this when he met with Mr. Blinken on Friday at the Great Hall of the People in central Beijing.

“China and the United States should be partners rather than rivals,” Mr. Xi said. “The two countries should help each other succeed ... rather than engage in vicious competition.”

Trade, technology, and economic issues between Beijing and Washington are increasingly major challenges for both sides but especially for Mr. Xi, as China’s economic growth has slowed and the U.S. has stepped up sanctions. Beijing charges that the U.S. seeks to contain China and curb its rise.

When raising this issue on Friday, Mr. Xi struck a conciliatory tone. “China is happy to see the confident, open, prosperous, and thriving United States. We hope the U.S. can also look at China’s development in a positive light,” he told Mr. Blinken. “This is a fundamental issue that must be addressed, just like the first button of a shirt that must be put right in order for the China-U.S. relationship to truly stabilize, improve, and move forward.”

China’s foreign minister, Mr. Wang, also highlighted Beijing’s concern about U.S. economic pressure, telling Mr. Blinken that “China’s legitimate development rights have been unreasonably suppressed.”

Protecting the market

For his part, Mr. Blinken stressed that the U.S. does not seek to hold back China’s development or decouple the two economies, telling reporters at the U.S. Embassy press conference that this would be “disastrous.”

Yet he said China’s government subsidies for leading 21st-century industries are distorting the market. He joined a chorus of senior U.S. officials, including Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, in charging that China is using unfair trade practices and subsidizing surplus production in key industries such as solar panels, electric vehicles, and batteries.

“China alone is producing more than 100% of global demand for these products – flooding markets, undermining competition, putting at risk livelihoods and businesses around the world,” Mr. Blinken said.

Overall, he added, “China is responsible for one-third of global production – but one-tenth of global demand. ... There’s a clear mismatch.”

Beijing has rejected “the so-called ‘China’s overcapacity theory,’” calling it a “false narrative,” a Chinese Foreign Ministry official was quoted as saying by the state-run Xinhua News Agency. “It is naked economic coercion and bullying.”

Given domestic political priorities in both countries – with Mr. Biden facing the November presidential election and Mr. Xi seeking to revive China’s sluggish economy – such frictions are unlikely to be resolved easily, experts say.

Nevertheless, these are also reasons Beijing and Washington both seek – at a minimum – to try to maintain stability in their relationship. “If Biden is reelected ... [and] no major accidents occur, the current trend of stable and improving U.S.-China ties will probably continue,” said Jia Qingguo, director of Peking University’s Institute for Global Cooperation and Understanding, in an interview published by the blog Sinification.

Today’s news briefs

• U.S. to replenish Ukrainian air defenses: It will provide Kyiv with additional Patriot missiles as part of a massive $6 billion additional aid package, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin announces.

• Call for U.N. investigation: A Palestinian civil defense team calls on the United Nations to investigate what it said were war crimes at Gaza’s Nasser Hospital, saying nearly 400 bodies were recovered from mass graves after Israeli soldiers left the complex.

• Floods kill dozens in Kenya: Flooding and heavy rains have killed at least 70 people since mid-March, a government spokesperson says, twice as many as were reported earlier this week. More than 130,000 people are currently affected by the flood.

• FTC on net neutrality: The Federal Trade Commission votes to restore rules that prevent broadband internet providers such as Comcast and Verizon from favoring some sites and apps over others, effectively reinstating an order the commission first issued in 2015.

• A quarterback scramble: Caleb Williams is heading to Chicago, aiming to become the franchise quarterback that the city’s NFL team, the Bears, has sought for decades. Five other teams selected quarterbacks among the top 12 picks, setting a record with five in the top 10.

Competing pressures of activism, order test colleges

As calls for campus order and safety rise alongside voices of anti-Israel protest, colleges and their leaders are facing an extraordinary test. The pressures are coming from both inside and outside.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

Leonardo Bevilacqua Staff writer

When Minouche Shafik was appointed as the 20th president of Columbia University last July, she was asked to describe her leadership style. The Egyptian-born, U.S.-educated economist told the school’s alumni magazine that she wouldn’t be seeking the spotlight.

After 10 days of tumult at Columbia, that is no longer an option for a university president who’s being assailed from all sides – students, faculty, and even politicians – for her handling of a spiraling crisis that has now spread to colleges and universities across the country. Months of protests over the Israel-Palestinian conflict reached a crescendo after Columbia cracked down last week on a pro-Palestinian student encampment on its quad.

In recent days, various school administrators have called in police to arrest demonstrators for violating policies against camping on school grounds and posing a threat to public safety.

The situation has created an extraordinarily difficult balancing act for university leaders, who are trying to thread a needle between encouraging free speech and academic freedom, and cracking down on antisemitism and making sure Jewish students feel safe on campus.

“I’ve never seen this much pressure from outside on college campuses and college presidents,” says Brian Rosenberg, a former president of Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Competing pressures of activism, order test colleges

When Minouche Shafik was appointed as the 20th president of Columbia University last July, she was asked to describe her leadership style. The Egyptian-born, U.S.-educated economist told the school’s alumni magazine that she wouldn’t be seeking the spotlight.

“I subscribe to Nelson Mandela’s philosophy that you should lead from behind when you can, and as part of the team as often as possible,” Dr. Shafik said.

After 10 days of tumult at Columbia, that is no longer an option for a university president who’s being assailed from all sides – students, faculty, and even politicians – for her handling of a spiraling crisis that has now spread to colleges and universities across the country. Months of protests over the Israel-Palestinian conflict reached a crescendo after Columbia cracked down last week on a pro-Palestinian student encampment on its quad, arresting some 100 protesters one day after Dr. Shafik testified before a U.S. House committee investigating antisemitism on campus.

Since then, the Columbia encampment has only sprung back, while others have sprung up in solidarity on campuses from Emory in Atlanta to the University of Texas at Austin, from Harvard to George Washington University. In recent days, various school administrators have called in police to arrest demonstrators for violating policies against camping on school grounds and posing a threat to public safety. Some have been forced to create virtual options for the final weeks of classes or relocate exam classrooms.

The situation has created an extraordinarily difficult balancing act for university leaders, who are trying to thread a needle between encouraging free speech and academic freedom, and cracking down on antisemitism and making sure Jewish students feel safe on campus. With just weeks to go before graduation, administrators are also scrambling to restore a general sense of order for their communities, including the many students not involved in the controversy.

Perhaps no one is in a more perilous position right now than Columbia's president, as the university senate voted to call for an investigation into campus leadership Friday, while she also was negotiating with protest leaders over a Friday night deadline to dismantle their tents. Many are watching to see whether she can placate Columbia’s circling critics on both the left and right. On Wednesday, Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson visited the campus and said the president should go unless she could immediately “bring order to this chaos,” amid jeers from onlookers.

“I’ve never seen this much pressure from outside on college campuses and college presidents,” says Brian Rosenberg, a former president of Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota. “The last time we saw anything like this was probably the late ’60s.”

Colleges have welcomed student activism

Some critics say these elite institutions are reaping what they themselves have sown. At highly selective schools like Columbia, where fewer than 4% of applicants are admitted, social justice and activism have been increasingly valorized in recent years, with prospective students encouraged to demonstrate a commitment to causes greater than themselves. Now these same institutions that have encouraged their students to seek change are trying to rein in protesters who say they are simply putting those ideals into action.

Of course, that doesn’t mean all students are inclined toward activism. For many simply trying to finish up their term or graduate and plan their next step, the protests and counterprotests have been mostly a distraction.

“It’s definitely more tense,” says Cole Donovan, a Columbia graduate student in education and philosophy, describing the situation in recent days. “We live on campus and so we could hear the helicopters, [which were] quite loud.” Speaking on Wednesday, Mr. Donovan, whose curly red hair was tucked under a baseball cap, seemed unfazed by the swarm of media around the pro-Palestinian encampment.

At the protest camp, a student in shorts and a dark-green T-shirt rifled through reusable grocery bags full of donated food and other supplies. When a passerby offered to donate more, he waved him off. “We’re good here. Try NYU or the New School,” he said.

Away from the encampment, a small group of pro-Israel students had taped up pictures of Oct. 7 hostages, an Israeli flag, and a “Bring them home” flag. A man facing the hostage photos began praying, his head bobbing up and down. Columbia has about 5,000 Jewish students and has a joint degree program with Tel Aviv University.

Commencement for undergraduates is scheduled for May 15. Dr. Shafik has said she wants Columbia students whose high school graduations were disrupted by the pandemic to experience a full ceremony.

But universities across the country are now bracing for protesters to disrupt the occasion. On Thursday, the University of Southern California canceled its main commencement ceremony after arrests of pro-Palestinian students at its campus the previous night. Last week, the university drew criticism when it canceled a speech by its valedictorian, a Muslim student who has expressed support for the Palestinian cause, citing safety concerns.

Columbia’s end of term was likely always going to be bumpy, given the roiling protests over the war in Gaza. But recent events have made normalcy seem even more tenuous.

A timeline of tension at Columbia

In her April 17 testimony to a Republican-led House committee, Dr. Shafik seemed determined not to fall into the rhetorical traps set for other university presidents during a similar hearing in December. At that hearing, University of Pennsylvania President Liz Magill, one of three presidents called to testify about antisemitism on campuses, had equivocated when asked if calling for genocide against Jews was protected speech. Four days later, under pressure from donors and lawmakers, she resigned. Claudine Gay, Harvard’s president, later went too.

By contrast, Dr. Shafik more forcefully condemned antisemitic speech on campus and revealed details of internal investigations into professors at Columbia accused of expressing support for Hamas. The armed group carried out the Oct. 7 attack in Israel that killed some 1,300 people and took hundreds of hostages. That attack led Israel to invade Gaza, where the local health ministry says over 34,000 people, mostly women and children, have since died.

Student protesters at Columbia have been calling for a cease-fire in Gaza and for the university to divest from companies that do business in Israel. While the protests have been nonviolent, some participants have made verbal threats toward Jews and voiced support for Hamas. On Friday, one of the Columbia protest leaders issued an apology after statements he had posted on social media came to light in which he said Zionists “don’t deserve to live.”

“Antisemitism has no place on our campus, and I am personally committed to doing everything I can to confront it directly,” Dr. Shafik told members of Congress.

The day after her Capitol Hill visit, Columbia asked the New York Police Department to dismantle a “Gaza solidarity encampment” that students had assembled on its main lawn in defiance of university policy. Over 100 students were arrested and later suspended by Columbia and Barnard, its sister college, though Barnard has since offered to revoke some of its suspensions.

Over the weekend, the situation escalated as pro-Palestinian protesters faced off against pro-Israel protesters, on and off campus, before Columbia closed its gates to the public and classes went hybrid. Over 100 faculty members walked out Monday to protest the police action and call on Columbia and Barnard to lift all student suspensions.

Instead of restoring order on campus and deflecting critics in Congress, Dr. Shafik has managed to alienate almost every constituency, says Professor Rosenberg, the former Macalester president who now teaches at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. “I understand how hard the job is, but I think this was a case of very bad judgment.”

Protests now versus the 1960s

In her April 18 request to the NYPD, Dr. Shafik wrote that the encampment posed “a clear and present danger to the substantial functioning of the University” and raised safety concerns for the community. It was the first time Columbia had summoned law enforcement since 1968. That year, amid sweeping national protests against the Vietnam War, nearly a thousand Columbia students were arrested after they occupied five buildings, took a dean hostage, and shut down the campus for a week.

Columbia isn’t facing a crisis on that scale now, and its leaders ought to have shown more restraint, says Robert Cohen, a historian at New York University and scholar of campus activism, who expresses dismay at the arrests of students. The pressures “on these administrations have made them much more willing to suppress dissent even when it’s not disruptive,” he says. “It’s a terrible precedent for violating free speech and academic freedom on campus.”

It’s also counterproductive, says Bettina Aptheker, a retired professor who co-led the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley in 1964, which set the stage for the student activism of the period. “When you repress them, you guarantee that more students are going to come out,” she says.

Steven Bahls became the president of Augustana College, a private liberal arts college in Rock Island, Illinois, in 2003. At that time, campus activism was mostly a nonissue; students seemed far more focused on getting jobs. But that changed over his 19-year tenure, he says, as subsequent generations began increasingly to flex their activist muscles and make demands of administrators.

That created new challenges over how to draw a line on free speech. “Sometimes free speech hurts,” says Mr. Bahls, a legal scholar. But colleges also have to ensure that speech doesn’t become harassment. “That’s the problem that presidents have. These two values clash, and there are no easy answers,” he says.

How social media changes protests

The current political climate, and the rise of social media, have exacerbated the problem, say analysts, as student activists today seem less willing to compromise, concede, or hear opposing viewpoints. Instead, they often seek to be the loudest voices on campus, with the goal of sparking viral moments. Add in zero-sum Israeli-Palestinian politics and a bloody war in Gaza, and the pressure has only grown on college presidents.

“Colleges have encouraged their students to think about changing the world. What they’ve not done a particularly good job of is preparing students to deal with viewpoints that are different from their own. And that is also part of what we’re seeing right now: an inability to engage in hard conversations,” says Professor Rosenberg.

NYU’s Professor Cohen says the crackdown at Columbia has already had one direct effect on him: Enrollment in his fall undergraduate class on student activism in the 1960s has spiked.

On Wednesday, Akua, a student from Africa who asked to go by first name only out of concern for privacy, was enjoying the spring sunshine on Columbia’s campus near the Israeli protest site. “My friends all the way around the world are telling me how lucky I am to be here, how inspired they are by the grassroots [protests],” she says. She adds, “Columbia recruits some of the most brilliant and driven students from around the world and then is shocked when they take action.”

Trump trial, Week 1: Fees, favors, and tabloid publisher

The role of David Pecker in Donald Trump’s hush money trial has revealed how much Mr. Trump and tabloid publishing have had in common.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

In July 2017, then-President Donald Trump asked National Enquirer publisher David Pecker to a White House dinner to thank him for help with his 2016 presidential campaign. As Mr. Pecker walked out, his host asked about Karen McDougal, a former Playboy centerfold whom National Enquirer had paid $150,000 to keep quiet about an affair she said she had with Mr. Trump in 2006.

“She’s doing well; she’s quiet. Everything’s good,” Mr. Pecker said.

Mr. Pecker described this scene as part of his testimony this week in Mr. Trump’s Manhattan criminal hush money trial. If nothing else, the opening days have underscored the commonalities between Mr. Trump and the world of tabloid publishing – and how intertwined they were – during Mr. Trump’s 2016 White House run and even into his first years in the presidency.

Mr. Trump has denied many of the prosecution’s allegations in this first-ever criminal trial of a former U.S. president. A jury will determine whether the actions outlined by Mr. Pecker and other witnesses constitute an illegal conspiracy to interfere in an election.

“I wanted to protect my company, I wanted to protect myself, and I also wanted to protect Donald Trump,” said Mr. Pecker during his testimony.

Trump trial, Week 1: Fees, favors, and tabloid publisher

In July 2017 then-President Donald Trump asked National Enquirer publisher David Pecker to a White House dinner to thank him for his help in the 2016 presidential campaign. The event was “for you,” President Trump told the tabloid boss, and he could bring friends and business associates with him to enjoy the Executive Mansion event.

As Mr. Pecker walked out after a memorable evening his host asked, “how’s Karen doing?” Both men knew “Karen” meant Karen McDougal, a former Playboy centerfold whom the National Enquirer had paid $150,000 to keep quiet about an affair she said she had with Mr. Trump over 10 months in 2006.

“She’s doing well; she’s quiet. Everything’s good,” Mr. Pecker said.

Mr. Pecker described this scene as part of his remarkable three days of testimony this week in Mr. Trump’s Manhattan criminal hush money trial. Step by step, he asserted that he and his company had agreed to act as Mr. Trump’s eyes and ears during the 2016 run for the presidency, identifying possibly troublesome stories prior to publication and burying them, while promoting stories damaging to Mr. Trump’s opponents.

Mr. Trump has denied many of the prosecution’s allegations – regarding hush money payments to another woman, Stormy Daniels – in this first-ever criminal trial of a former president. A jury will eventually determine whether the actions outlined by Mr. Pecker and other witnesses constitute an illegal conspiracy to interfere in an election.

But if nothing else, the opening days of the trial have underscored how much Mr. Trump and the world of tabloid publishing had in common – and how intertwined they were – during Mr. Trump’s 2016 White House run, and even into his first years in the presidency.

“I wanted to protect my company, I wanted to protect myself, and I also wanted to protect Donald Trump,” said Mr. Pecker at one point in his testimony. He was referring to his efforts to suppress Ms. McDougal’s allegations of an affair. But in doing so, he might also have been describing his long association with Mr. Trump, the real estate magnate and reality TV star who once sat in the Oval Office, and may again.

First meetings and plans for “success”

In his testimony Mr. Pecker said he and Mr. Trump first met in the late 1980s or early 1990s at Mar-a-Lago. Their friendship blossomed after the publishing executive suggested they develop a quarterly “Trump Style” magazine. With all the hotels, casinos, and golf courses that the Trump Organization owned it would be a sure success, Mr. Pecker told Mr. Trump, since it had a guaranteed distribution network.

They would meet every few months to go over cover photos and content for the magazine, he said. Then in 1999 Mr. Pecker bought the National Enquirer. Mr. Trump was one of the first to call, saying he had purchased “a great magazine.”

In the early 2000s Mr. Trump’s developing stardom on “The Apprentice” series of reality TV shows took their business dealings to a new level. Mr. Trump would send over stories about the show’s ratings, the interactions of its cast, who would be fired in the next show, and so on, according to Mr. Pecker’s testimony. It was a “great, beneficial” interaction, Mr. Pecker said. Mr. Trump got free publicity with a supermarket tabloid read by millions, and Mr. Pecker got free content.

At the height of “Apprentice” ratings, National Enquirer’s own research showed Donald Trump was the best person to put on their cover to drive reader interest. As talk of a possible Trump presidential run increased, an Enquirer poll found that 80% of its readers wanted him to be a candidate. Mr. Pecker told Mr. Trump this, he testified, and Mr. Trump boasted about it on “The Today Show” during an interview with Matt Lauer.

In June of 2015, Mr. Pecker received an email from Michael Cohen, Mr. Trump’s personal attorney and fixer. It invited him to sit in a prime Trump Tower atrium floor seat to watch Mr. Trump’s declaration of his candidacy.

“No one deserves to be there more than you,” said the email, which prosecutors displayed for the New York jury.

In August of 2015 Mr. Pecker met with Mr. Trump and Mr. Cohen at Trump Tower. They asked the tabloid executive what he and his publications could do to help the Trump presidential campaign. Mr. Pecker testified that he replied he would run positive stories about Mr. Trump, and negative stories about his opponents, and that in addition he would be the campaign’s “eyes and ears” in the information marketplace.

Following the meeting, Mr. Pecker told the National Enquirer’s East Coast and West Coast Bureau Chiefs that if they heard whispers of any developing story about Mr. Trump or his family he would like to hear about them first. That would give him time to “catch-and-kill” any potentially bad stories – purchase them, and then bury them without publication.

In October 2015, one of the Enquirer’s top editors told Mr. Pecker that he had received a tip that a doorman named Dino Sajudin was trying to sell a story that Mr. Trump had fathered a child with a maid who worked at Trump Tower.

“Absolutely not!” said Mr. Cohen, when asked about the veracity of the story. But Trump Tower records showed both the doorman and the maid had indeed worked at Trump Tower, Mr Pecker testified. Eventually the Enquirer paid Mr. Sajudin $30,000 to “take the story off the market,” in Mr. Pecker’s words.

Then the Enquirer hired a private investigator. They sent reporters to the location where the illegitimate child reportedly lived.

“And we discovered it was absolutely, 1000 percent untrue,” Mr. Pecker testified.

Mr. Sajudin remained “very difficult to deal with,” said Mr. Pecker. Eventually the Enquirer released him from his contract, allowing him to shop the story elsewhere – but on December 9, 2016, after the election was safely past.

The case of Ms. McDougal was more complicated. In early June of 2016 the Enquirer West Coast Bureau Chief received a tip that a lawyer was shopping rights to the story of a former Playboy model who alleged she had a romantic relationship with Mr. Trump for nearly a year, earlier in the decade.

Mr. Pecker developed a sense that Mr. Trump at least knew the model, due to the way he called her by her first name and spoke about the issue. Eventually Mr. Pecker said that he paid $150,000 for her story, and for fitness articles and tips she would provide to his magazines.

Asked by prosecutors if Mr. Trump wanted to bury Ms. McDougal’s allegations to prevent embarrassment to his family, Mr. Pecker said he did not think so.

“I thought it was for the campaign,” he said.

A few days prior to the election, the Wall Street Journal published the story, revealing the allegations of the affair and the fact that the Enquirer had bought it to kill it. Mr. Trump was furious, Mr. Pecker testified.

“Catch-and-kill”

Mr. Pecker’s testimony brought the story of the case right up to the brink of the key figure in the Trump campaign’s “catch-and-kill” effort: Stormy Daniels.

In October, 2016, the Enquirer heard through the same source that had provided the tip about Karen McDougal that the porn star was trying to sell a story of an encounter with Mr. Trump.

“I am not doing it, period,” Mr. Pecker told Mr. Cohen, according to his testimony.

According to Mr. Pecker, he did not want the National Enquirer associated with a porn star – WalMart was one of its biggest distributors, and the company might balk if it ever found out. Nor did he want to pay out the cash. He had not been reimbursed for the payment to Ms. McDougal, and he was becoming nervous about the campaign finance implications of the effort.

Eventually the Federal Election Commission fined the Enquirer’s parent company $187,000. In the end, Michael Cohen took out a home equity line of credit and paid Ms. Daniels the $130,000 himself. (Mr. Trump denies that he ever had sex with her.)

The prosecution alleges that Mr. Trump repaid Mr. Cohen $420,000 – the initial payment, plus taxes, plus a separate payment to a polling firm for rigging online surveys, plus a bonus – via checks disguised as payment for legal services.

These disguised checks are at the heart of the business fraud charges in the case. The jury will surely hear more about them, as well as about Ms. Daniels, in coming days.

Mr. Pecker ended his testimony on Friday by saying that he regards Mr. Trump as a mentor, and recounting that the billionaire was the first person to call him when Robert Stevens, a journalist for the Enquirer parent company, died after letters containing anthrax were mailed to multiple U.S. media outlets following the September 11 attacks.

“Even though we haven’t spoken [recently] I still consider him a friend,” said Mr. Pecker.

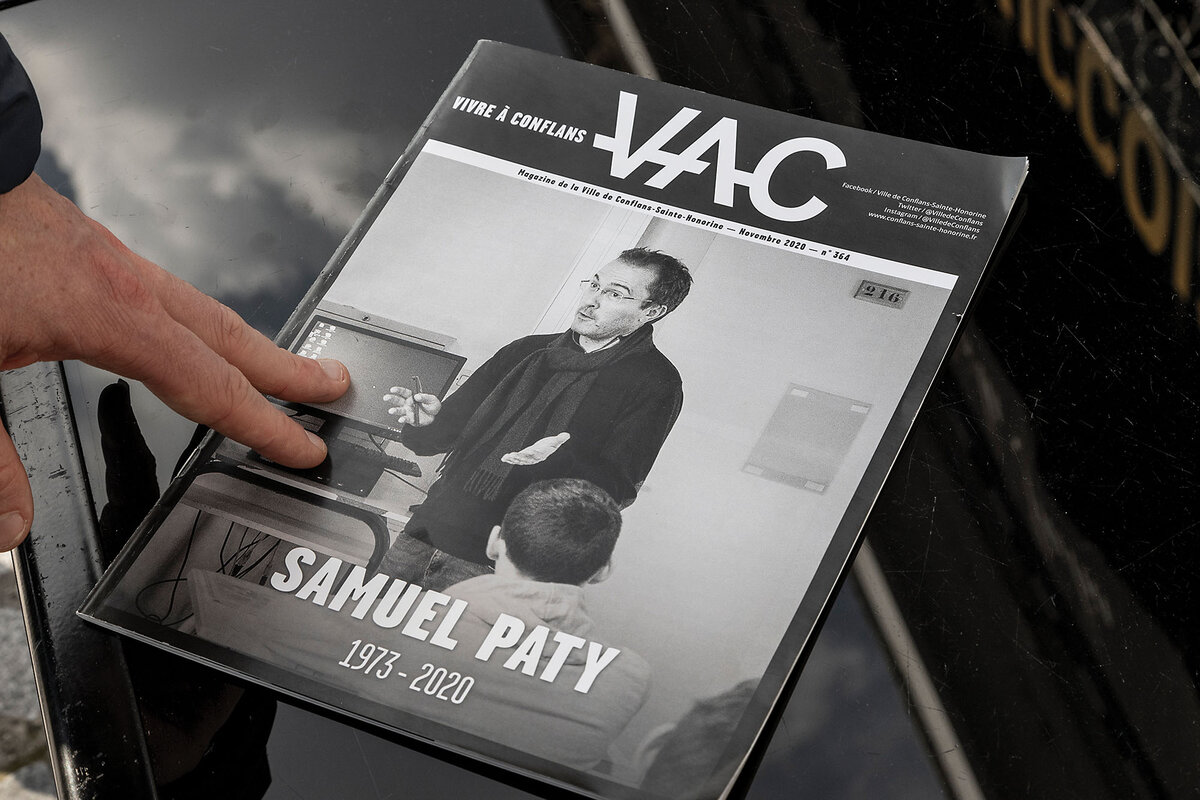

How Samuel Paty murder affected teaching in France

School should be a sanctuary. But when controversy over showing a cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad in class led to the killing of teacher Samuel Paty in 2020, colleagues had to wrestle with what felt like a profound breach of trust.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 19 Min. )

When a French teacher was beheaded in 2020 for showing a cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad, the murder reverberated across France. Muslims felt targeted, and the nation’s vaunted system of secular education came under scrutiny. Yet perhaps most of all, the killing shook the connection between teachers and their students.

One student’s lies led to rumors that fanned the flames of anger around the teacher, Samuel Paty. Another student pointed out Mr. Paty to the man who would eventually kill him. One teacher at the school was not sure she’d ever be able to trust her students again. “At first, I hated them,” she says.

The years since have brought deep introspection. What is the role of teachers in a country where education is at the center of a profound clash of cultures? And how do they move from fear to rebuilding the essential bond with students?

Healing remains a work in progress. But the tragedy has also created a new openness and honesty. Says the teacher, “This whole experience has allowed us to ask questions, understand each other, and tell our side of the story.”

How Samuel Paty murder affected teaching in France

It was a Friday afternoon in October 2020, and Coralie, a junior high school French teacher at Collège du Bois d’Aulne, had just gone for a walk in the nearby woods with her dog to clear her mind before the two-week school vacation.

It had been a stressful week. Her co-worker, Samuel Paty, had shown controversial images in his history class, and the whole school was on edge. That morning, she had tried to say hello to Mr. Paty but felt he was avoiding her gaze, scuttling off to class instead of making the usual jokes or initiating a game of table tennis in the teachers lounge.

She was back home when the messages in her teachers WhatsApp group started flooding in. Murder in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine. Decapitation. Teacher, dead.

Coralie switched on the TV. And then everything crumbled.

“I knew right away it was Samuel,” she says.

It has been three years since a teacher who loved rock music and talking philosophy was beheaded by a Muslim man in a Paris suburb, where crisp hedges trimmed to perfection line up in front of white stucco houses. Three years since Mr. Paty’s own student spread the lie that would eventually get him killed.

The murder reverberated across France. Many Muslims said they felt targeted in response. The country’s vaunted secular culture received fresh scrutiny. Yet perhaps most of all, the killing shook the connection between teachers and their students. Held up as the advance guard of French culture and intellectualism, French teachers had a near-sacred relationship with students. Now, educators are no longer sure how to do their jobs.

Coralie is still reckoning with the series of events that led to Mr. Paty’s death. How did showing an image of the Prophet Muhammad in class end with a teacher dead? Did the students who pointed out Mr. Paty to his would-be assailant know the consequences of their actions? Weren’t they just kids?

“For weeks, I had nightmares. I stayed in my house with the blinds drawn,” says Coralie, looking out towards the Seine River at a local café. Like the other teachers in this story, she requested to use a pseudonym to protect her safety. “How could our students, who we trusted, turn around and do this? At first, I hated them.”

Since Mr. Paty’s death, France has continued to wrestle with its notions of secularism – laïcité – and the importance of freedom of expression.

Mr. Paty was the first teacher to die for what he taught in class, but he has not been the last. In October 2023, French teacher Dominique Bernard was stabbed in the northern town of Arras by a former radicalized student, supposedly for the French values he represented. And at the end of February, a school principal in Paris received death threats after asking a female Muslim student to remove her headscarf.

While the right to blaspheme is protected by French law, Mr. Paty’s murder has raised questions about where the line is between freedom and provocation.

Those questions are at the heart of what threatened to drive wedges between teachers, parents, and students at Bois d’Aulne, and between teachers themselves. Some agreed with what Mr. Paty had done, and some didn’t. Several left the school after his death, shaken by the event. Others left teaching entirely.

For Coralie and those who decided to stay, the hate is starting to fade away. Forgiveness is slow, but coming. Now, three years later, what she, her colleagues, and residents of all faiths in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine desperately want is to learn to trust again – in their students, each other, and themselves.

“Teaching is not always easy. ... We’re definitely more careful now,” says Joëlle Alazard, a high school history teacher and the president of the Paris-based Organization for History and Geography Teachers. “But we’re pushing ahead and teaching controversial subject matter.

“When students have their arms crossed and don’t dare ask questions, we have a problem. But when we know a class well and trust each other, we can have a debate and move things forward together.”

It was an average fall day in early October 2020 when Mr. Paty decided to show two caricatures from the French satirical paper Charlie Hebdo, featuring the Prophet Muhammad, to his oldest students during a class on freedom of the press and freedom of expression.

The choice was intentional. Even if showing images of the Prophet is considered blasphemous in Islam, France prides itself on being a secular country – especially within its education system. Was Charlie Hebdo being unnecessarily provocative, or was it within its rights? Where was the moral line?

Mr. Paty told students ahead of time that they could leave the classroom if they wished or close their eyes. The lesson went forward without incident, but later, a female student told her father that Mr. Paty had shown students images of a naked man, calling him the Prophet Muhammad, and forced her out of class because she was Muslim. On Oct. 8, Brahim Chnina posted a video on Facebook, calling his daughter’s teacher a pervert and lodging a complaint of pornography with the police.

Soon Mr. Chnina’s video was circulating on the social media pages of a Paris-area mosque and on WhatsApp groups in France and abroad. In one week, the video accumulated 13,000 views.

“I had friends in Algeria who were telling me about this video,” says Soraya, whose son was a student in Mr. Paty’s class on the day he showed the images. To protect her family, she asked to be identified only by a pseudonym. “I called the father and tried to reason with him, but he was incensed with rage. There was no getting through to him.”

Soraya sent a message to Mr. Paty in support, on behalf of the Muslim community. Then it came out that Mr. Chnina’s daughter wasn’t even in school on the day Mr. Paty showed the images – she had been given two days of suspension for bad behavior and presumably wanted to lash out.

But the damage had been done. Rumors began swirling around the schoolyard. What had Mr. Paty really shown in class? Should he have done it? Was he truly anti-Muslim?

Four days before his murder, the principal of Bois d’Aulne held an emergency meeting with teachers. The local administrative office had been notified, and police lined the front door. Unbeknownst to anyone, Mr. Chnina’s video had reached Mr. Paty’s would-be assailant, a Chechen Muslim refugee named Abdoullakh Anzorov.

“Samuel told us not to worry, but at this point, we really realized it was serious,” says Coralie. “At that meeting we asked, ‘Are there risks?’ You could feel this oppressive atmosphere at school.”

Then, on Oct. 16, Mr. Anzorov waited by the school gates, pulling a 14-year-old student to the side and offering him €300 (about $325) to identify Mr. Paty. The teenager, along with four others, accepted.

As Mr. Paty left the school at around 5 p.m., Mr. Anzorov beheaded him with a 12-inch-long knife on a street in nearby Éragny. Minutes later, Mr. Anzorov was shot and killed by police. But Conflans-Sainte-Honorine, and France, would never be the same.

Mr. Paty’s murder caused shock waves. While France is no stranger to terrorism, the attack of a teacher had shattered something sacred. Mr. Paty was given a state funeral, broadcast nationwide from Sorbonne University, at which French President Emmanuel Macron said that Mr. Paty had been the victim of hatred and misunderstanding, and that his death would not be in vain.

“We will continue to defend the freedom that you taught as well as laïcité,” Mr. Macron said. “We will not stop showing caricatures even when others back away.”

But despite Mr. Macron’s unwavering confidence, France was still trying to reconcile its vision of secularism with an increasingly diverse nation. It was also still reeling from the events of 2015, which had set the stage for Mr. Paty’s murder and become a defining moment in how France viewed terrorism then and now.

In January of that year, Islamist extremists stormed the Paris office of Charlie Hebdo and killed 11 journalists for their publication of satirical content related to the Prophet Muhammad. Later that November, Islamist terrorists again launched a violent spree across Paris, killing over 130 people at the Bataclan concert venue and restaurants around the city.

In the months that followed, France faced a wave of further attacks in cities such as Nice, Villejuif, and Rambouillet. In response, the government pushed through a series of anti-terror laws that would grant police and intelligence agencies extended powers. It also began employing the term laïcité more often in reference to French values. Following the January attacks, then-Prime Minister Manuel Valls said laïcité needed to be “proudly displayed ... since we’re being attacked because of it.”

Soon, laïcité was under threat everywhere. Muslim women were stopped on French beaches for sporting burkinis, or for wearing a hijab on city buses, in public institutions, or while driving. Religious symbols had already been prohibited in French schools since 2004, and now there were questions over whether veiled mothers could accompany students on class outings.

By the time Mr. Paty decided to show the Charlie Hebdo caricatures to his class in 2020, the French education system had become a battleground for laïcité.

“One of France’s biggest accomplishments when it broke with the Catholic Church [starting in the French Revolution] was its national education system,” says Philippe Gaudin, the director of the Institute for Religious Studies and Laïcité. “Until [1886], the church held full control. After that, French schools became the sanctuary of laïcité as a political project and not just a rule about respecting religious freedom to maintain public order.”

When France signed the 1905 law on the separation of church and state, religion was seen as an “enemy of the state,” says Mr. Gaudin, and laïcité was a reaction against this authoritarian regime. France’s education system was to be a place of free thought and speech, where all students, regardless of religion, had the right to learn.

But with those protections of laïcité has come debate about its reach. Though the nation came together in mourning after the 2015 attacks – defending its secular values in the face of radical Islam – France also saw a more than threefold jump in Islamophobic acts. Nearly half of French Muslims say they face discrimination based on their faith.

“We’re suffering greatly over the conflation between Islam and terrorism; the idea that our religion could produce violence,” said the French Council for the Muslim Faith in a press release following Mr. Paty’s death. “[At the same time], we must remain dignified, serene, and lucid in the face of hostility and anti-Muslim acts.”

And while the initial concept of laïcité was used by French leaders to ensure that religion – Catholic or otherwise – never controlled the country’s public services or education system again, it has often felt anti-Muslim by members of that community. Mohand-Kamel Chabane, a history teacher in Paris who wrote a book in 2022 about teaching in diverse, working-class neighborhoods, says that “many people, Muslims in particular, think that laïcité is used to prevent them from being free.”

In the past decade, the French government has regularly introduced legislation involving pieces of Muslim dress in education, sports, and public life. This past September, Prime Minister Gabriel Attal announced that the long, loose-fitting abaya would be banned in French public schools.

“The idea of laïcité has gone from being something related to freedom towards a way to control the visibility of religion in the public space,” says Valentine Zuber, a French historian and expert in religious freedom. “Now, it’s laïcité as a notion of identity, and people bristle at the thought of a piece of fabric [covering a woman’s head] year after year.”

For Bertrand Bujaud, there is a clear before and after: before Mr. Paty was murdered, when Mr. Bujaud enjoyed a certain trust in himself as a teacher and a father, and after, when he realized that he could be killed for doing his job.

“It was the worst day of my life,” says Mr. Bujaud, a history and geography teacher at a neighboring school in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine. When the news broke about Mr. Paty, he says, his phone rang off the hook for an entire day.

“At first, there were few details about what had happened. We heard it was a 40-something male. A history teacher. In Conflans-Sainte-Honorine. Everyone thought it was me.”

Then there was the dilemma of how to break the news to his sixth grade daughter, who was a student in one of Mr. Paty’s classes but did not see the cartoons. He decided to tell her that her teacher was a hero, like Jean Moulin during the French Resistance.

But internally, Mr. Bujaud was trying to reconcile his thoughts about how to teach sensitive content going forward. History teachers were the only ones within the French national education program mandated to teach moral and civic education. They had a responsibility to impart concepts like freedom of speech and laïcité to their students. But what was the threshold between developing critical thinking and pushing a debate too far?

“Of course we need to defend freedom of expression, but teachers are supposed to remain neutral and show restraint,” says Denis Ramond, a political scientist who has written extensively about satire and freedom of expression. He was also working as a junior high school French teacher at the time of Mr. Paty’s murder.

“Teaching freedom of expression works if you explore it in a historical context, but it gets tricky once you move into contemporary debate.”

In the week between when Mr. Paty showed the cartoons and when he was murdered, controversy had started brewing. Even if Mr. Chnina had failed to rally a significant number of Muslim parents, many were conflicted on whether Mr. Paty should have shown the cartoons or invited students to leave class. Soraya says her son told her the night before that Mr. Paty was planning to show the cartoons the following day.

“I told him, ‘We live in France. You go to school in France. Take this opportunity to learn everything you can.’ I was OK with it.”

But other Muslim parents resisted. In an emergency meeting between parents and the school principal, one mother said that the class was supposed to be on freedom of expression. If not all students were allowed to participate in the lesson, didn’t that defeat its purpose?

The cracks were equally beginning to show in the teachers lounge. Two wrote emails to the rest of the staff saying they didn’t agree with what Mr. Paty had done.

“[Our colleague] committed an act of discrimination,” wrote one teacher in an email published in the graphic novel “Crayon Noir” (“Black Pencil”) about the week before and the week after Mr. Paty’s death. “We should never send our students out of class, no matter how, just because they practice a certain religion or come from a certain background.”

The chaos sent teachers spiraling. It was a moment that could have broken their bond for good. And while around a third of teachers during Mr. Paty’s era have now left, in the aftermath of his death, they came together in their grief.

“After [he was murdered], the teachers who had been against Samuel immediately apologized; they obviously felt terrible,” says Coralie. “His murder created an instant solidarity between us. We all felt we had to continue to fight his fight.”

But the sense of trust between teachers and students was different. After all, it was a student who had spread the initial lie about what Mr. Paty had shown in class, and students who had pointed out Mr. Paty to his attacker.

The peer pressure at school meant that a majority of students – regardless of their faith – believed the rumors that Mr. Paty was Islamophobic and had acted out of malice. Those who felt otherwise were too scared to speak out. Most had seen the photo of Mr. Paty beheaded on social media, and one student had even encouraged others to “like” it. For teachers at Bois d’Aulne, these are the wounds that are taking the longest to heal.

“I have asked myself so many questions about this relationship of trust. Up until last year, some students still believed that the rumors about Paty were true,” says Mattias, an English teacher at Collège du Bois d’Aulne, joining Coralie at a café in Conflans. “For €300, would they single us out [to an attacker]? Could it be any of us? Where is this heading?”

Chantal Anglade wants to help teachers at Bois d’Aulne put these questions to rest. Ms. Anglade runs the French Organization for Terrorism Victims, and inside her Paris-area office, photos from her group sessions line the wall in a colorful collage. In one image, a dozen teachers and students from Bois d’Aulne sit in a semicircle, shoulders hunched, covered by masks leftover from the COVID-19 pandemic.

One month after Mr. Paty was attacked, Ms. Anglade reached out to staff at Bois d’Aulne, and for the past three years, she has been leading regular workshops with teachers and students who lived through Mr. Paty’s murder. The goal has been to encourage both sides to speak their minds, dissect their emotions, and eventually heal.

“It’s giving them permission to verbalize the facts and especially the rumor,” says Ms. Anglade. “Even recently, some students were still rejoicing in what happened to Mr. Paty and saying, ‘He deserved it.’ This was something that absolutely needed to be addressed, but not head-on.”

Ms. Anglade brings victims of other terrorist acts to each session to share their stories, in an attempt to help students and teachers learn from those who have been through similar trauma. She also calls teachers by their first names in front of students to remind them they’re human, too. In one exercise, each side wrote letters, detailing what they couldn’t yet say.

“You could see the tenderness and affection students had for their teachers, some of whom they’d seen break down in tears in class,” says Ms. Anglade. “They just wanted them to be OK. And that repairs something. It’s beautiful.”

In another activity, Ms. Anglade worked with students to explain why blasphemy was prohibited in Islam but allowed in France, and what that meant for teaching freedom of expression. Though Ms. Anglade insists that Muslim students did not express feelings of discrimination to her, she says the exercise went a long way toward building understanding among students of all faiths, as well as between students and teachers.

“French society’s view of Muslims is always negative. We’re radicalized, violent – a problem,” says Mounira Chatti, a professor at Université Bordeaux Montaigne who studies integration. “So it’s easy for Muslims to feel targeted when terrorist acts happen, and to get defensive.

“Young people absolutely need more education about different religions. That automatically builds tolerance. Ultimately, both sides need to take steps towards one another.”

In the year following Mr. Paty’s murder, French filmmaker Christine Tournadre spent eight months at Bois d’Aulne filming the documentary “Le Collège de Monsieur Paty” (“Mr. Paty’s Junior High”) about the rebuilding process. That experience also helped teachers and students address their mutual mistrust. Often, Ms. Tournadre would ask them to speak their mind to the camera. Other times, they would chat together with the camera off. Now, when Coralie is in front of her students, she feels like she’s in a protective bubble.

“This whole experience has allowed us to ask questions, understand each other, and tell our side of the story,” says Coralie. She and Mattias say it was eye-opening to realize how much students were affected by having their friends implicated in Mr. Paty’s murder. “We realized, OK, we’re all human.”

“Now we have something to leave for the next generation of teachers who come here,” says Mattias. “We want to make sure the burden is as light as possible.”

But there was still the problem of the group of students who had pointed out Mr. Paty to his attacker. Right after he was murdered, none of the teachers knew much of anything, but as the days went by, they noticed that some students were consistently absent from class. Six in all.

“A colleague told me, ‘You know, one of your students was involved.’ It was like the whole world collapsed,” says Coralie. “It was like a second stabbing, one that was almost more painful than the first [of finding out about Samuel]. We give everything to our students, never thinking they’ll betray us. I couldn’t digest it.”

Coralie says she has only been able to truly process what happened and make peace with her students – who were between 13 and 15 years old at the time – when their trial concluded this past December.

There, the female student who told the initial lie was given an 18-month suspended prison sentence, while the student who initially took the bribe from Mr. Paty’s attacker received the harshest sentence of two years in prison.

Around a dozen teachers joined Mr. Paty’s family as plaintiffs in order to be able to attend the trial and see for themselves the motives of their former students – to know that when they took the money, the students didn’t intend for Mr. Paty to die.

It was also a way to come to terms with the fact that, while their pain was different from that of his family, ex-partner, and son, the teachers were victims, too.

“At first, they didn’t necessarily think they were victims. They thought, ‘Paty was the victim or the family is the victim,’” says Antoine Casubolo Ferro, the lawyer representing the teachers at the December trial. “But they needed to be recognized for what they’d suffered, too. What they went through was not negligible. Just because you don’t have physical wounds doesn’t mean it doesn’t hurt.

“It allowed them to trust in themselves again. It’s definitely been a huge part in their personal reconstruction.”

Teachers across France continue to fight for their right to teach freely and without fear. In early December, two months after the murder of the Arras teacher, a junior high school teacher in the Paris suburbs was accused of making racist comments and excluding Muslim students, after she showed the 17th-century painting “Diane and Actaeon,” which features women with their breasts exposed.

In March, a French senator put forth 38 recommendations to address the rise in pressure, threats, and attacks against teachers across the country.

For Bois d’Aulne, the support of other teachers and the broader community has been crucial. The year after Mr. Paty’s death, the Organization for History and Geography Teachers created the Samuel Paty Award. Now it’s in its third year, and junior high school students can compete for the prize by putting forth a project within the moral and civic education program that exemplifies the values Mr. Paty stood for.

“We’re trying to create more freedom at school and teach students how to live alongside one another better,” says Ms. Alazard, the organization’s president. “We didn’t want to be stuck in regret and grief. We were afraid Samuel Paty’s name would be forgotten.”

In Conflans-Sainte-Honorine, it’s almost impossible to forget what happened here three years ago. At a recent book signing for the graphic novel “Crayon Noir,” a local library was standing room only. Tears flowed among teachers, city council members, former students, parents, and residents.

“Samuel Paty was killed so he could be silenced,” says Maria Escribano, a city council member in Conflans-Sainte-Honorine, after the book signing. “So we have to speak for him.”

Every year, City Hall organizes a memorial service in the town center in Mr. Paty’s honor, as a reminder to residents of the importance of keeping Mr. Paty’s memory alive. Laurent Brosse, the mayor of Conflans-Sainte-Honorine, says his diverse community stuck together after Mr. Paty’s murder. When Muslim residents showed up for the one-year anniversary, they say they were met with gratitude for their presence.

“Some Muslims in our community didn’t go because they were scared [of a backlash], but we went because it was a way to show our mutual suffering,” says Soulaimane Chemlal, a local psychologist who lived on the same street where Mr. Paty was murdered. “We wanted to show our kids that what happened was extremely serious and went against any religious framework. We needed to show our solidarity.”

Each October, teachers and students at Bois d’Aulne lead their own commemoration on school grounds. While there has been discussion about changing the school’s name to Samuel Paty, teachers and students remain at odds.

But otherwise, there is strong unity. François, an English teacher who joined the school the year after Mr. Paty’s death, says that he was intimidated at first but has been impressed by the staff’s sense of togetherness. Now, he says, he sees Bois d’Aulne as a school “like any other.”

Today, a floor-to-ceiling image of Mr. Paty, bursting with color and light, hangs in the hallway outside his former classroom. After his death, teachers also planted a ginkgo tree next to the lunchroom in Mr. Paty’s name, to represent strength, hope, and resilience. Like the teachers’ relationship with their students, the tree only continues to grow and breathe new life into the school.

“Former students often write us messages to see how we’re doing, or we’ll see each other on the street and say hello,” says Coralie. “We don’t try to run away from what happened. It has united us forever.”

Black independent library is still making history

At the Monitor, we love a good library story. And Western Library in Louisville, Kentucky, has a great one to tell.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Natalie Woods remembers the Rev. Thomas Fountain Blue’s cursive handwriting. The first time the librarian held his papers, they changed her life.

Ms. Woods never learned about Western Library’s history when she grew up in Louisville, Kentucky.

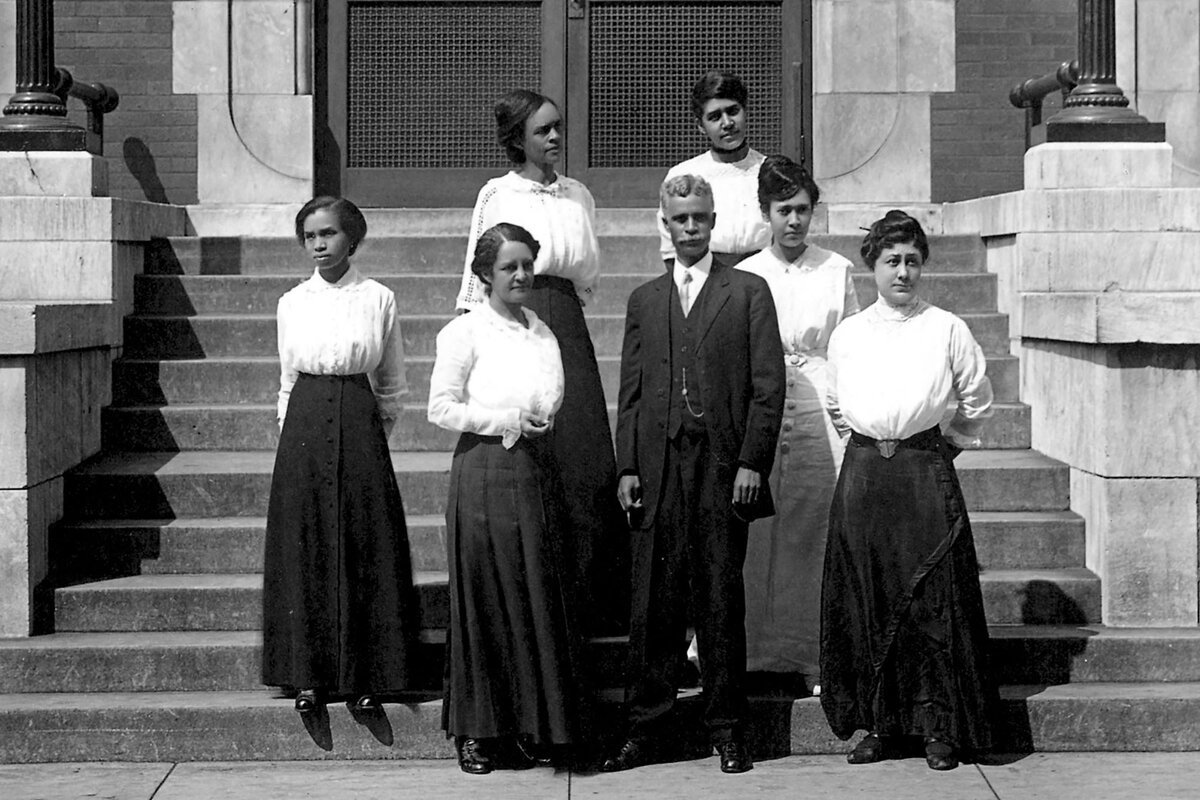

The library under her care is the oldest public library in the United States independently run by and for African Americans. It was also the earliest training ground of Black librarians in the South.

The “Western Colored Branch” of the Louisville Free Public Library system opened in 1905.

The segregated library was considered an experiment, says Ms. Woods. Blue, its first manager, had no formal schooling in library science – because there were no library schools open to Black people.

Blue not only ran a successful library but also started the first training program for Black library workers. The course became the prototype for the first degree program in library science for African Americans.

It is a legacy that has changed Ms. Woods’ life, and preserving it has become her vocation.

“There is so much history right here,” she tells a group of high schoolers.

Black independent library is still making history

Thirty minutes into the library tour, Louisa Sarpee wants to work there.

History is so close to her. One block away from her high school, the small library she had never set foot in laid the foundation of African American librarianship. What is more, the library was created by a former principal of her own school. Its archives even house a diploma of her school from the time the word “colored” was still in the school’s name.

“Is there any way to volunteer at the library?” the ninth grader asks Natalie Woods, the librarian giving the tour. “I’m obsessed with everything here.”

“Say no more, girlfriend,” Ms. Woods replies, beaming. “We’re gonna talk.”

For Ms. Woods, the manager of Louisville’s Western Library, the gasps coming from the group of 18 students learning about its history is no surprise. She meets Louisvillians every day who know nothing about Western. The library under her care is the oldest public library in the United States independently run by and for African Americans. It was also the earliest training ground of Black librarians from around the South. It is a legacy that has changed Ms. Woods’ life, and preserving it has become her vocation.

“There is so much history right here,” she tells the group. “It is now your assignment to make sure it’s not forgotten.”

Training ground for South’s Black librarians

The “Western Colored Branch” of the Louisville Free Public Library system opened in 1905, in an era when Black communities across the South were building institutions in the wake of emancipation, says historian Tracy K’Meyer at the University of Louisville. (The name later became Western Library.)

The segregated library was considered an experiment, says Ms. Woods. Its first manager, the Rev. Thomas Fountain Blue, had no formal schooling in library science – because there were no library schools open to Black people.

Blue not only ran a successful library, which led to the creation of a second “colored” branch in Louisville. He also started the first training program for Black library workers. The course became the prototype for the first degree program in library science for African Americans, which opened in 1925 at Hampton Institute in Virginia.

In 2003, the American Library Association recognized Blue’s “leadership role” in “laying the foundation for the continued presence of African American libraries, library students, and library employees in all types of libraries within the United States and abroad.”

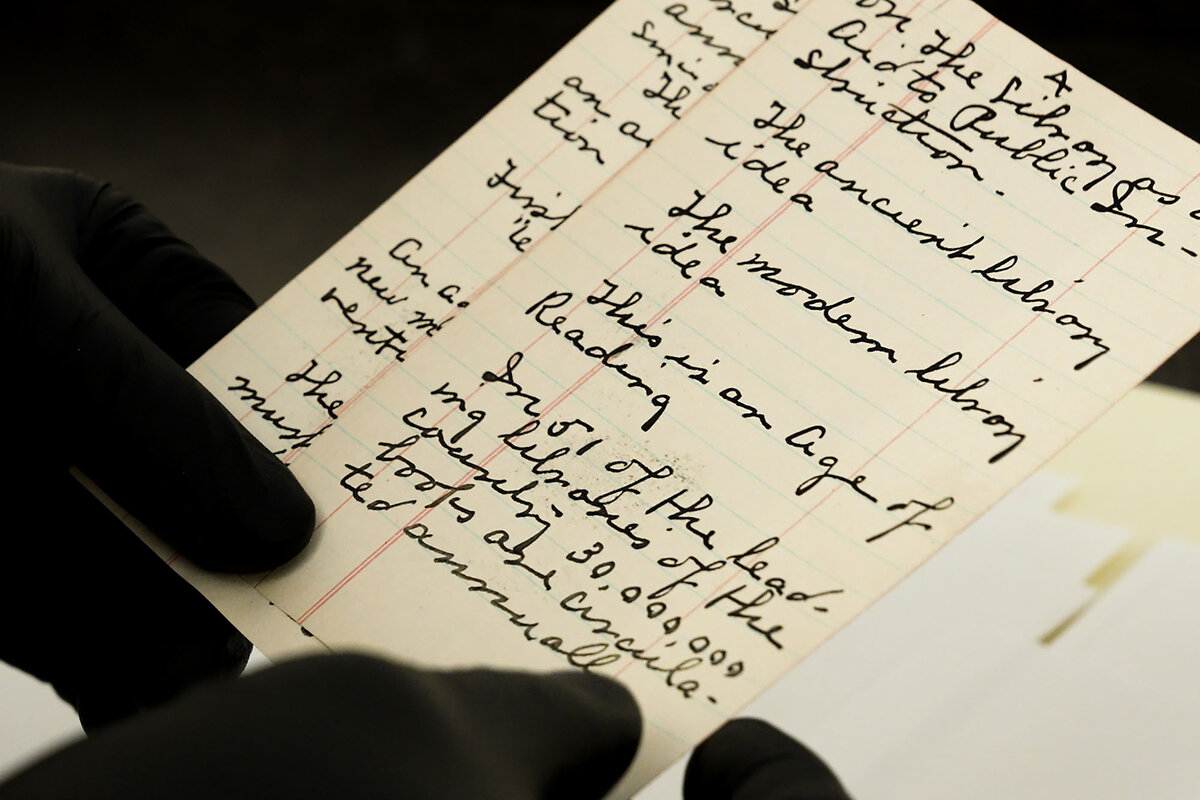

Ms. Woods remembers Blue’s cursive handwriting. The first time she held his papers, they changed her life.

She never learned about Western’s history when she grew up in Louisville. The child of a Black father and a white mother, she became a page at Louisville’s Shawnee Library. There, she would hear mentions of Western’s history.

In 2008, while working as a library clerk and attending college at night, Ms. Woods lost the vision in her left eye due to complications from surgery. She couldn’t perceive distance properly and had to relearn basic activities, such as picking up a pencil, by repetition. It was a struggle to finish college, she says, and she gave up the idea of pursuing a master’s degree in library science.

Then, one day, a supervisor brought Ms. Woods a folder of documents to transcribe. They were the papers of Thomas Fountain Blue.

On lined sheets, the cursive hand discussed circulation methods, library cards, and a library’s role in educating the public.

“I knew of him, but I didn’t know how deep and intentional he was in everything he did,” Ms. Woods says. “And it just gave me a new love and desire to go to library school.”

She obtained her library degree at Florida State University. She became Western’s manager on March 6, 2016: Blue’s 150th birthday.

“Where everyone may feel at home”

When Ms. Woods started at Western, she found that many people living near Western did not even know the library exists.

The library’s archive, which includes Blue’s papers and a wealth of material on Black Louisville history, was disorganized. There was no indexing, and the room was not even locked down, Ms. Woods says.

So she started giving tours of the library, which she still offers about once a week. In 2018, she obtained a $70,000 grant to index and digitize Western’s archive.

It is an important archive that sheds light on “how Black librarians, in real time, were trying to imagine what a library to serve a Black community should look like,” says David Anderson, a professor of English at University of Louisville.

Blue was “incredibly proactive and inventive in placing library collections where they would be used: ... public schools, barbershops, businesses, places with foot traffic,” says Professor Anderson. He was “bringing people into the branch, and taking the branch out to the people.”

Aside from cultivating a varied collection – from W.E.B. Dubois to Henrik Ibsen to Charles Darwin – Blue also made Western a community center “where everyone may feel at home and share equal privileges,” Blue wrote in a speech on Louisville’s “colored” libraries in 1927.

“During a single month ninety-three meetings for educational and social uplift have been held in the buildings,” he wrote.

A child of formerly enslaved parents, Blue attended college and seminary in Virginia and ran a Louisville YMCA before starting at Western. He died in 1935, after being denied medical care for a treatable infection, says Annette Blue, his granddaughter.

“He died from Jim Crow laws,” she says in a Zoom interview from her home in California.

In the early 1960s, Black protesters staged sit-ins in various cities to challenge library segregation, which became outlawed nationally by the Civil Rights Act. Meanwhile, Blue lay in an unmarked grave in Louisville’s Eastern Cemetery until 2022, when Ms. Woods had a headstone installed.

“You are their legacy”

“How many of you sit and talk to your parents and grandparents about how they grew up?” Ms. Woods asks Louisa and her schoolmates. A few raise their hands.

“You should. That’s your history,” Ms. Woods says. “You are their legacy.”

Ms. Woods says she does her work in honor of Blue and her parents. She tries to embody Blue’s commitment to “the betterment of his people.” Her parents, who faced much opposition to their relationship as an interracial couple, taught her to “treat people the way you want to be treated.”

Western sits in a low-income neighborhood. Every day, patrons come in for the free Wi-Fi and to use the library’s computers to look for jobs. Ms. Woods and her staff offer patrons one-on-one tutoring in basic computer skills and reading.

“She will see you through to the end of what you need,” says Maggie Bailey, a resident who has received computer training at Western over the past two years.

Sometimes, Ms. Woods says, patrons talk down to her because she is a woman, or say nasty things about her race. But Ms. Woods lets it “roll off [her] back.”

“I think about Reverend Blue,” she says. “I imagine he faced all those kinds of things back at that time, too. So I just keep my head up.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why this Olympics feels festive

Soon after Olympic swimmer Lydia Jacoby won her first gold medal in 2021 at the Tokyo Games, she graced the winners’ podium in a white tracksuit, her red hair tied up in a bun and her face hidden – under an N95 mask. Because of COVID-19 restrictions, the American athlete had to place the medal around her neck herself. With family members banned from attending, her parents watched her on TV from Florida.

What a difference three years makes. The pandemic is over and Paris will be hosting this year’s Summer Olympics. Fans from around the world can visit the Games, bursting with pride and encouragement for their favorite athletes.

This year’s Games may be more than just a welcome return of international sports. For two weeks, the world will enjoy a respite from global strife, bringing people together to cheer, laugh, and cry for good reasons. No talk there of elections, natural disasters, or what world leaders must do to fix problems. When the first Olympic competition starts in July, it will be a signal for celebration. And the winners can again bow their heads to let someone bestow a medal.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Is it possible to conquer fear?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

As we become more aware of our true nature as God’s children, held safely by divine Love, we can break free from roller coasters of fear that would keep us from experiencing progress and healing.

Is it possible to conquer fear?

Sometimes we may feel plagued by fear, and hope to gain some semblance of peace that seems elusive. But we can find comfort and healing in the Bible’s fearless view of life. The book of Isaiah encourages, “Fear not, for I am with you; be not dismayed, for I am your God. I will strengthen you, yes, I will help you, I will uphold you with My righteous right hand” (41:10, New King James Version).

Even the mere thought of entirely letting go of fear can be startling. But God, divine Love, shows us that we’re not vulnerable mortals living in a hazardous universe. As spiritual and harmonious children of God, we’re actually safe and free to do good.

Here are some articles from the archives of The Christian Science Publishing Society that show how freedom from fear isn’t a far-off or naive dream. It’s the natural outcome of the realization that at any moment, we can know and feel God’s love and protection.

The author of “Breaking through the world’s chains” shares how even when it seems the world is falling apart around us, we can find freedom from debilitating fear and panic attacks as we see that, in truth, everyone dwells safely in God’s kingdom.

Fear can’t ever really stop God’s expression of goodness and wholeness in each of us, His spiritual and good creation, the author of “Eliminating fear from decision-making” realized.

The author of “What to do if you’re feeling afraid” describes how she was able to literally and figuratively get “back in the saddle” after a serious horseback riding injury. As she “became aware of the encompassing and powerful presence” of God’s love, her fear of getting back on a horse dissolved.

As we practice seeing divine Love expressed all around us, we find freedom from anxiety, as a brief podcast titled “Can you live without anxiety?” explains.

Viewfinder

Nature’s piling on

A look ahead

Thanks for ending your Friday with us. Come back next week. We’re working on stories ranging from the year of global farmer protests to the complexity of regulating TiKTok and other social media platforms, to a surge in youth participation in Polish democracy.