- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Ten years after a banking crisis, Americans still feel the ripples

- ‘Not intimidated’: In trade fight with US, Canada returns to opposition roots

- Colleges respond to opioid crisis with paths that emphasize ‘recovery’

- S. Sudan’s midwives, lifted by aid, wonder how long donors will deliver

- In California, sheltering the chinook salmon after pushing it to brink

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Cycles that won’t strengthen storms

As hurricane Florence looms off the US East Coast and a monster typhoon threatens the Philippines, each brewing up a modern-era ferocity ahead of making landfall, first thoughts go to the safety of those evacuating and of any who’ve had to stay and brace.

The storms will arrive, then leave. Long recovery will follow. Governments' responses will be reviewed. And as the impact is assessed – including in the United States the possible fallout of inland flooding in an agricultural region – a background debate will be recharged:

How much is humanity contributing to the preconditions for severe weather, and what more might it be doing to change them?

It’s hard to ignore that the US administration took steps this week to make it easier for companies to release methane, a major greenhouse gas. But others focused on a helpful act of intake: An innovative assault was begun against an 88,000-ton “garbage patch” in the Pacific Ocean.

What might become of that material? There’s standard recycling for now. But, in a small step, researchers at two British universities have just produced evidence of a way to use light to turn plastic waste into hydrogen fuel. While still prohibitively expensive to produce at scale, hydrogen power (derived through a chemical reaction, not combustion) has, as its “emission” … water.

One hopeful new cycle to consider as a hot planet makes itself felt.

Now to our five stories for your Thursday, including three on reaches for recovery: of many Americans a decade after a stock-market collapse, of college students confronting addiction, and of a deeply stressed California river-dweller.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Ten years after a banking crisis, Americans still feel the ripples

The financial crisis that erupted 10 years ago is a reminder of linkages and interdependence. Global investors became the spark, yet lasting impacts still linger for many Americans.

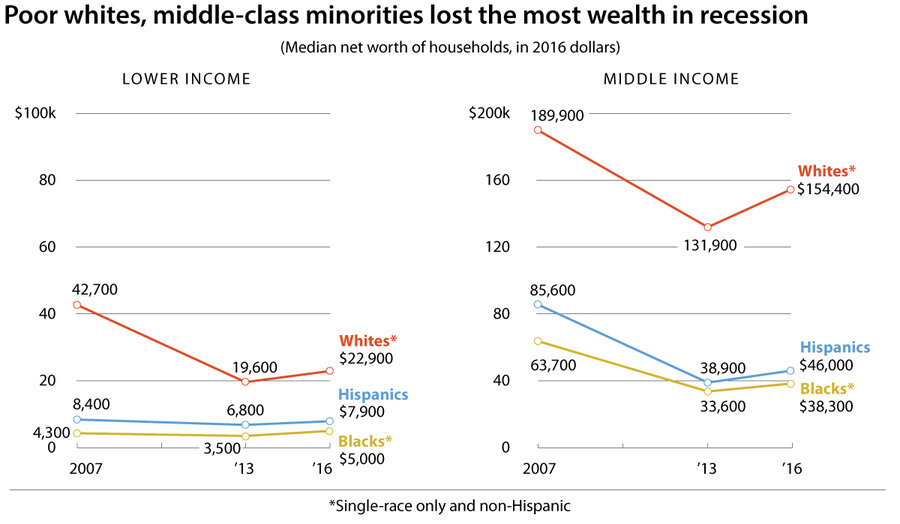

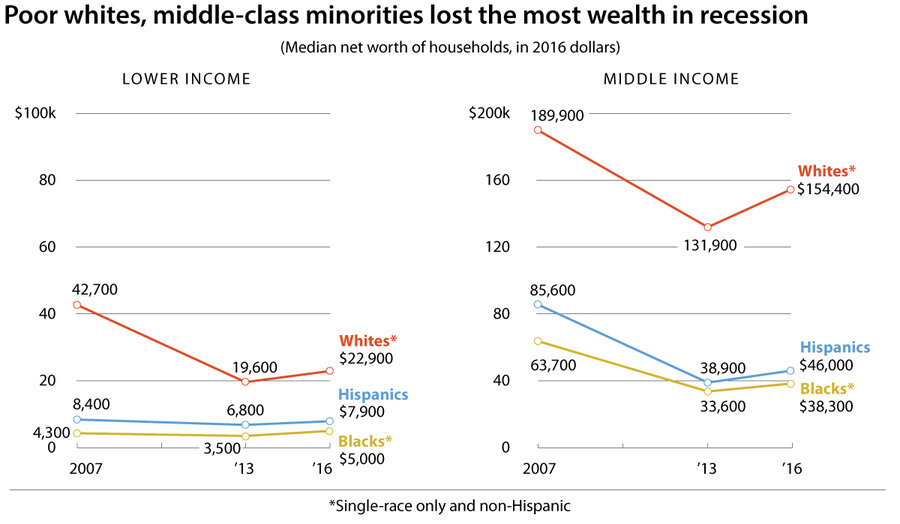

Ten years ago this week, the US investment bank Lehman Brothers collapsed under the weight of high-risk real estate investments gone bad. That signaled the most dire phase of a financial crisis that had already been simmering. And it spurred policymakers toward all-out fiscal and monetary support for the financial system, which staved off a potential chain reaction of bank failures. But if a second Great Depression was averted, the crisis took a lasting toll on American households. An investor-fueled housing bubble went bust. More than 5 million Americans lost homes, and many more saw their net worth plunge along with home prices. “I couldn’t keep up,” says Shirley Thomas, an African-American grandmother in Brockton, Mass. A foreclosure-prevention program helped keep her in her home. As of 2016, median net worth was still well below 2007 levels, with middle-income black and Hispanic-American households especially hard hit alongside lower income white households (see chart). Many families have made progress. But Anne Depew, of the Boston-area foreclosure prevention program, says that “so many Americans are just one hardship away from disaster.”

Ten years after a banking crisis, Americans still feel the ripples

After buying her Brockton, Mass., home in 2005, Shirley Thomas had to work three jobs to make the $3,000 monthly payment. When she was so overworked she had to give up one of the jobs – grocery shopping for the elderly – she began to fall behind on her mortgage payments.

That’s when the foreclosure walls began to close in.

“I couldn’t keep up,” says the African-American grandmother.

Like Ms. Thomas, many Americans went through the wringer of the Great Recession and came out poorer on the other end. A decade later, many still have not made up the lost ground. It wasn’t just the loss of income or jobs – the stuff of every recession – that made the downturn so bad. It was the concurrent financial crisis and the resulting flood of foreclosures that caused many Americans to lose their homes and, as a result, their wealth.

Unlike income, wealth is harder and usually slower to amass, involving paying off a mortgage or building up a business. As of 2016, the latest figures available, the typical American household’s wealth had still not recovered. In 2007, it had $139,700 in inflation-adjusted dollars; by 2016, it was only $97,300.

And the recovery has been uneven. In general, black and Hispanic families were hit especially hard, and their recovery since the crash remains especially far from complete. Poor whites, too, saw severe losses – with median net worth in 2016 at half its 2007 level.

“It's really only upper income families that have recovered,” says Rakesh Kochhar, a senior researcher at Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan think tank based in Washington. At lower incomes, “whether you are white, Hispanic, or black, your wealth in 2016 was less than what you had before the recession.”

When financial services firm Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy on Sept. 15, 2008, it triggered the darkest phase of a financial crisis that ripped through the banking system. Investors worldwide had already shifted from bullish to panicked, as a boom in dodgy mortgages was seen to have tainted the prospects of US financial firms. When Lehman went bust, without a buyer or emergency government funding to support it, the entire financial system seemed at risk.

The stock market plunged, as did home prices. Borrowers who had recently bought homes, often with mortgages that required little or no down payment, found they owed more than their homes were worth. Banks increasingly foreclosed on delinquent borrowers.

The long tail of a banking panic

Between 2008 and 2014, the US experienced 5 million outright foreclosures, according to ATTOM Data Solutions, an Irvine, Calif., firm that tracks real estate. That total doesn’t include the forced sales of homes and “short sales” where lenders accepted a loss on mortgage debts. Whatever equity people had built up in their homes was often lost.

Lower-income African-Americans, though pummeled by the loss of income and jobs during the Great Recession, were spared somewhat from the loss of wealth – partly because so many were renters rather than owners, with little net worth to begin with. By 2016, they were one of the rare groups to be doing better than before. Lower-income Hispanics followed a similar path, though not yet a full recovery. (See chart.)

Pew Research Center, based on Federal Reserve survey data

Middle-class Hispanic households, by contrast, lost more than half their wealth, and in 2016 the median was 46 percent below the pre-recession level. Middle-class black households saw a slightly smaller decline and now are down 40 percent. While middle-income white households weren’t hit as hard, the typical lower-income white household saw a 44 percent dive in wealth. (One reason lower-income whites were more affected than lower-income minorities is that they are far more likely to own a home.)

Overall, the wealth gap between whites and minorities increased between 2007 and 2013, according to the Pew study. The white-to-black wealth ratio for middle-income households rose from 3-to-1 to 4-to-1 and the white-to-Hispanic ratio from 2-to-1 to 3-to-1. The gaps between upper-income families and all other income groups, minority and white, now stand at record highs.

Foreclosures and recovery on Main Street

Brockton, a poor and diverse city in Plymouth County south of Boston, followed the national trend. The rate of homes in the county receiving a foreclosure notice quintupled between 2006 and 2008. While the rate never got near some boom-and-bust areas like Las Vegas’s Clark County, Plymouth nevertheless led the state in the rate of foreclosure filings from 2009 through 2015.

“Brockton was the epicenter of the foreclosure crisis in Massachusetts,” recalls John Buckley, the county’s register of deeds. “Home prices rocketed downward. So a lot of people lost value in their assets,” even those who didn’t get foreclosed on.

By 2016, the city’s already high poverty rate had worsened for blacks and Hispanics. It stayed level for non-Hispanic whites.

Since then, real estate has boomed and the job market is so strong that companies are starting to raise pay. Nationally, income for the typical US household rose to a record $61,400 last year, after adjusting for inflation, although the figure is not statistically different from 2007, the Census Bureau reported Wednesday. But black household income fell slightly last year, after two years of solid growth.

The recovery of wealth could be slowest for many at the bottom rungs of the income ladder, although analysts are reluctant to speculate. “It takes wealth to gain more wealth,” says Valerie Wilson, an economist with the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank in Washington. “It could take another several decades and maybe longer than that, depending on where we’re going in terms of policy.”

Thomas counts herself fortunate. Although her bank was preparing to foreclose, a foreclosure prevention program called the SUN Initiative, stepped in to buy the house. The home was valued close to $400,000 when Thomas bought it in 2005. The group convinced the bank to sell it for $120,000 and then resold it to Thomas. Now, Thomas’s mortgage payment is $1,500.

“It’s half of what I was paying before,” she says. Thomas figures her financial position has recovered from the Great Recession's impact. “I’m not worse off…. Now, I'm down to one [job].” Next year, she plans on retiring, “but I’m not going to fully retire,” she adds.

The SUN Initiative, one of the programs of impact-investing firm Boston Community Capital, has nearly 60 borrowers in Brockton who were saved from foreclosure.

“We don't think of them as high-risk,” says Anne Depew, general manager of the initiative, which operates in seven states. “We are talking about people who are school teachers, police, firefighters. It shows that so many Americans are just one hardship away from disaster.”

Pew Research Center, based on Federal Reserve survey data

A deeper look

‘Not intimidated’: In trade fight with US, Canada returns to opposition roots

It's easy to assume that a peaceful border means the nations that share it have no tensions between them. But Canada often defines itself by its differences from the US and is doing so again.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

President Trump has been widely unpopular in Canada since before his election, but his threats of the “ruination” of Canada in renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) have left Canadians not only surprised but angered. Some dismiss Mr. Trump’s moves as boorishness that market forces will eventually curtail. But he’s raised anxious questions about how dependent Canada, which sends 75 percent of its exports south, remains on the United States. And that has translated into a surge of grass-roots patriotism at the grocery store and travel agency, with a #BuyCanadian movement taking off on social media. It has also rekindled a form of nationalism, which in many Western countries translates into the exclusion of others but in multicultural and multilingual Canada more often takes the shape of anti-Americanism. “It’s always there, the sense that we are different than the Americans,” says historian Jack Granatstein. “We are loyalists; they are rebels. We believe in peace, order, and good government, not life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. There’s always a sense that somehow the United States is out of step with us. And at no point is that clearer than the present.”

‘Not intimidated’: In trade fight with US, Canada returns to opposition roots

Thomas Jefferson, in drumming up support for war against the British Empire in 1812, boasted that capturing the territory that is now Canada would be a “mere matter of marching.”

That sense of American superiority was voiced 206 years ago. But it feels uncomfortably familiar to modern-day Canadians like Eugene Oatley, a descendant of a United Empire Loyalist – American colonists who fled north at the Revolutionary War and sought refuge under the British Crown.

As President Trump threatens the “ruination” of Canada in renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Canadians are not only surprised, but angered. Old complexes about the Canadian-American relationship, one that has been among the most peaceful in the world for two bordering countries, are resurfacing.

“Trump is using the same old bullying tactics, it is like 200 years all over again,” says Mr. Oatley, who on a blustery day is standing at Lundy’s Lane in Niagara Falls, site of one of the fiercest battles of the War of 1812. No side could declare outright victory, not unlike the competing visions of victory in the war itself. But for British North America, the battle thwarted a US advance and takeover – and showed how misguided the American Founding Father’s war rhetoric was.

“You have to face bullies,” Oatley says, adding that it is as true now as then. “You can’t run away from them.”

Some have dismissed Mr. Trump’s moves as boorishness that market forces will eventually curtail. But his tactics have raised anxious questions about how dependent Canada, which sends 75 percent of its exports south, remains on the US. They've also rekindled a form of nationalism, which in many Western countries translates into the exclusion of others, but in multicultural and multilingual Canada more often takes the shape of anti-Americanism.

“It’s always there, the sense that we are different than the Americans,” says historian Jack Granatstein, who wrote the book “Yankee Go Home? Canadians and Anti-Americanism,” which traces an undercurrent of anti-Americanism in Canadian society since the American Revolution. “We are loyalists, they are rebels. We believe in peace, order, and good government, not life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. There's always a sense that somehow the United States is out of step with us. And at no point is that clearer than the present.”

“Trump has made every Canadian government that follows aware that you can’t trust the Americans now.”

Formed in opposition to the US

Canada was built upon a vision that was explicitly distinct from the US, starting as early as 1776. The Loyalists were the first significant wave of English-speaking settlers in Canada and fundamental to its identity. Today the United Empire Loyalists’ Association of Canada is still a popular club – Oatley sits on the board of the largest of the branches in Niagara, loyalist heartland at the US border. Their patriotism is seen in the initials “UE” they place after their names to affirm their heritage.

This region, along the Great Lakes, later became the main theater of the War of 1812, with battlegrounds dotting the landscape along the Niagara River. The conflict confirmed a wariness of the US and the need to defend itself – the war’s resistance heroes are some of the most celebrated historic figures – which would continue through the founding of Canada.

When the Province of Canada with New Brunswick and Nova Scotia joined together to create Canada in 1867, the driving motivation was to resist an American invasion – and American-style extremes.

“We were terrified of a United States that had just gone through a civil war,” says Michael Adams, president of the Environics Institute for Survey Research, which measures Canadian attitudes. “There were a lot of things that Canadians didn't like about the United States – slavery, civil wars, guns, and violence,” he says. “So we we actually formed ourselves in opposition to the United States.”

In the last century, as the US grew as the world’s superpower, staking positions that were controversial around the globe, Canada worked hard to find its own place, consuming American culture and products but often at pains to define itself as, above all, “not American.” Canadian governments often disagreed with American foreign policy positions, from the Vietnam War to the invasion of Iraq in 2003. But trade barriers continued to fall, bringing down with them political ones as well.

Dan Ciuriak, an international trade expert at the C.D. Howe Institute, a think tank in Toronto, says that despite continual disputes, both economic and political, convergence has been the dominant theme of the past generation, even after 9/11 when fears of terrorism caused the US to fortify its borders. “In Canada and the US there's this narrative of ‘we don't just trade together, we build things together, we do things together,’ and while there was a thickening of the border post-9/11, which was never really resolved, there was still that sense that the relationship was this one of partnership,” he says.

For many, Trump’s actions have proven that illusory.

Trump has been widely unpopular in Canada since before the election, but tariffs issued on the grounds of “national security” were deeply offensive to most Canadians. Weeks later he dissed Prime Minister Justin Trudeau after the Group of Seven meeting in Quebec as “weak,” an insult that buoyed support for the Canadian leader across the political spectrum.

In the latest spat, the US seemed to shut Canada out of NAFTA negotiations, forging a deal on the sidelines with Mexico and then giving Canada a deadline to sign or leave it. As talks have stalled, Trump has hurled successive insults, threatening to put tariffs on cars, which TD Bank analysts have shown could cost Canada 160,000 jobs, the majority in Ontario.

Trump has tried to back Canada in a corner, to force Ottawa to open the Canadian dairy or cultural market or loosen the independent trade dispute system. In the midst of negotiations he told reporters in off-the-record comments that the US will not compromise with Canada. “It’s going to be so insulting they’re not going to be able to make a deal,” he said, according to the Toronto Star, which published the bombshell remarks.

Canadians 'not intimidated'

Trudeau has been criticized by some for misplaying the US, by others for playing it up. “Trump stirs the nationalism, and Trudeau is riding it,” Granatstein, the historian, says.

Oatley says Trudeau has no choice but to stand strong. He says the US can't “ruin” Canada. “Trump could hurt us,” he says, “but that would hurt the US too.”

Trudeau said this week that auto tariffs “would be devastating, obviously, to the Canadian auto industry, but it would also be devastating to the American auto industry.” Members of the US Congress and industry leaders have come out backing Canada, saying they will not support a trade deal without all three original NAFTA signatories on board.

“Canadians are shocked and appalled, but they're not intimidated. All this mindless bluster is really not affecting the Canadian position in these negotiations,” says Gordon Ritchie, a former Canadian ambassador for trade negotiations and deputy chief negotiator of the Canada-US free-trade agreement. “It's not just rhetoric to say that Canada will only sign on to a good deal.”

But in the trade maelstrom, attitudes have shifted. Since Trump was elected, more Canadians hold unfavorable views of the US than favorable ones, for the first time since Environics began measuring opinions in 1982.

At the grassroots level, the clash has translated into a surge of patriotism at the grocery store and travel agency, with a #BuyCanadian movement taking off on social media. When Canada announced $12.6 billion in retaliatory tariffs this summer, only 20 percent of Canadians said they were opposed, despite the vulnerable economic position that Canada finds itself in.

And while Canadians say their protest is not directed at Americans, individual Americans are feeling it. Eddy Ng, an economics professor at Dalhousie University’s Rowe School of Business in Halifax, is conducting a study of American expats in Canada with Thomas Koellen of the University of Bern in Switzerland. The two started collecting experiences in the Canadian workplace after Trump was inaugurated.

Professor Ng says that more than half of respondents say they feel they are treated differently because of nationality. At the same time Canadians, whose multiculturalism is celebrated as part of the national identity, don’t see American-bashing as politically incorrect. That inconsistency goes back to geography and history, Ng suggests. “We always define ourselves by what the Americans are not.”

Testing the limits of US-Canadian friendship?

Michael Byers, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Global Politics and International Law at the University of British Columbia, says Canada over the years has moved further away from the US, particularly over culture war issues from guns to gay marriage. Today that is no clearer than at the top, where Trudeau has come to symbolize the liberal world order and Trump the populism nipping at its edges. He says those trends continue – but they aren’t necessarily anti-American in nature, and the vast majority of Canadians distinguish between the administration and the American population.

“Canadians are very concerned by how [Trump] has turned a very positive bi-national relationship into a hard-nose bargaining game,” Mr. Byers says. “Trump will cause a greater degree of divergence, and that certainly has Canadians pulling together. Not against the United States, but against the Trump administration.”

Not all sound such an optimistic note for the future of the relationship. In a commentary in The Globe and Mail, Laura Dawson, the director of the Canada Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington, recalls the words of former Prime Minister Jean Chrétien days after 9/11, when he declared that Canada would stand behind the US because the friendship has no limit.

“Or does it?” she asks in the piece. “Looking back on Sept. 14, 2001, I wonder whether Canadians will ever again feel that same sense of solidarity with the United States. Will our flags ever overlap as proudly and easily as they did then?”

Mr. Adams, of the Environics Institute, reaches back even further, to the oft-cited words of former President John F. Kennedy, who defined the Canadian-American alliance in Ottawa in 1961: “Geography has made us neighbors. History has made us friends. Economics has made us partners. And necessity has made us allies. Those whom nature hath so joined together, let no man put asunder. What unites us is far greater than what divides us.”

Many Canadians hope Kennedy’s words will endure the political disruption from Washington nearly 60 years later. But today they feel less an ally and more like “the little sister,” as Adams puts it. “We’ll feel badly, we might cry, but I don’t know what we can do. Our only authority is moral authority.”

Colleges respond to opioid crisis with paths that emphasize ‘recovery’

Long condemned as a moral failing, addiction is increasingly seen as a public health issue. Some US colleges are adapting to that perception shift in the ways they extend treatment.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Kelly Field The Hechinger Report

For years colleges have taken a reactionary approach to substance abuse, often seeming to be in denial about its existence unless a tragedy occurs. But the increase of opioid use and the changing views of addiction – from moral failing to public health issue – are bringing more attention and more public dollars to the subject. Collegiate recovery programs, almost unheard of five years ago, are multiplying amid an opioid epidemic that claimed the lives of 4,110 Americans under age 25 in 2016, the last year for which the figure is available. That’s almost double the number of young people who died of opioid overdoses in 2006. Collegiate recovery programs are also increasing: There are about 200 now, up from a couple dozen in 2013. The programs offer support and even housing, which can help with staying sober. “For the students who are involved with them, they’re absolutely life-changing,” says Christopher Freeman, community recovery supervisor at The College of New Jersey. “If we don’t pay now to help people recover and lead productive lives, we will pay later.”

Colleges respond to opioid crisis with paths that emphasize ‘recovery’

The first time Cherise tried college, she lasted only a couple of months.

Lonely and miserable, the Rutgers University freshman turned to heroin, and quickly became addicted. She dropped out of school and after what she describes as an “intentional overdose” in 2014, wound up in a rehab facility near the campus in New Brunswick, N.J., just down the street from fraternity row.

It was there that she heard about Rutgers Recovery House, a year-round dorm where students recovering from drug and alcohol addictions can find friendship and sanctuary from the temptations of college life.

Believing it was “meant to be,” she re-enrolled at Rutgers, and moved into the Recovery House.

“I was home,” says Cherise, who, like all the students in the house, asked that her last name not be used. Now 28, she graduated in the spring.

Almost unheard of five years ago, collegiate recovery programs are multiplying amid an opioid epidemic that claimed the lives of 4,110 Americans under 25 in 2016, the last year for which the figure is available. That’s almost double the number of young people who died of opioid overdoses in 2006.

Those statistics, and a flurry of seed funds from state governments and nonprofit organizations, are compelling colleges to take the often joked-about issue of campus drug use much more seriously, acknowledging a problem that still makes many campus leaders — especially in recruitment, development, and alumni offices — uncomfortable.

Before opioids, colleges “were able to sweep it under the carpet better,” says Christopher Freeman, community recovery supervisor at The College of New Jersey in Ewing. Students were abusing drugs and alcohol — they just weren’t as likely to die.

In 2013, there were a couple dozen collegiate recovery programs; today, there are around 200, according to advocates.

Changing attitudes toward addiction

The epidemic has also accelerated a shift in attitudes toward addiction, these advocates say. Long condemned as a moral failing, addiction is increasingly seen as a public health issue, worthy of public dollars. New Jersey, West Virginia, and North Carolina all provide grants to colleges toward the cost of running recovery programs. New Jersey’s legislature passed a law in 2015 requiring most public colleges to have recovery housing.

Research suggests that recovery programs benefit both students and colleges. One national survey found that students who participate in such programs have higher grade point averages than their peers and are more likely to graduate. Just 8 percent relapse, on average.

Still, collegiate recovery programs remain relatively rare — fewer than 5 percent of campuses have them — and many college leaders remain skeptical they’re even needed. There’s not a lot of data on addiction among college students, and what little there is suggests that, contrary to depictions in popular culture, they abuse drugs at lower rates than their peers who aren’t enrolled.

One in 5 full-time college students reported using an illicit drug other than — and usually in addition to — marijuana at least once in the previous 12 months, a national survey by the University of Michigan for the National Institutes of Health found. That’s slightly lower than the 24 percent of recent high school graduates who aren’t in college who said they’d used them. Another survey, by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found rates of illicit drug use among all 18-to-25-year olds to be as high as 38 percent.

But advocates for the recovery programs say many college leaders are in a state of willful denial, reluctant to admit a problem that might harm their institutions’ reputations or dampen recruitment.

“They don’t want parents walking around campus seeing posters that imply there is any kind of a substance abuse problem on campus,” says James Winnefeld, a retired U.S. Navy admiral and former vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff who started an organization to tackle the opioid epidemic after his son overdosed in his dorm room last year, just four days after enrolling as a freshman at the University of Denver.

This semester, DU opened a community center for students who are in recovery. While the center does not offer housing, a spokeswoman says the college plans to set aside a floor of an existing apartment complex for recovery housing next year.

Other collegiate recovery programs are long established. The first was created at Brown University in 1977, by a classics professor who was himself recovering from an alcohol addiction. Rutgers followed suit in 1983, after a student who had been drinking fell from some bleachers and became paralyzed. But the real growth has come since 2013, when a nonprofit organization called Transforming Youth Recovery began offering grants to colleges to start programs. Over the past five years, the nonprofit, which was started by a woman who lost her son to an opioid overdose, has given out $1.3 million in grants to 161 colleges.

Recovery programs vary in size and scope, but most offer 12-step or other support groups, “sober social” events, and awareness-raising activities, according to a survey by Transforming Youth Recovery. Just under half provide professional counseling, and roughly 10 percent include housing. A few have started offering medication-assisted treatment, weaning students off of opioids with the help of drugs that lessen their cravings for them.

The Rutgers approach

At Rutgers, the Recovery House is much more than a chem-free dorm. For Cherise and the 24 other students who live there, it’s an antidote to the loneliness that many people recovering from an addiction feel among peers who don’t understand why they can’t have “just one drink.”

“I don’t want to have a glass of wine, I want the whole bottle. It’s so hard to tell another person what that’s like,” says Andrea, a graduate student. “Here, I don’t feel alone.”

The dorm is also a refuge from the broader campus, where a culture of casual drug use and binge-drinking can jeopardize recovery. Advocates refer to colleges as “recovery-hostile” environments.

“There are triggers anywhere you go — there’s just more on a college campus,” says Devon, who is a rising sophomore. “You go outside and you smell weed. It’s easier to get drugs here than anywhere else.”

There are two things that keep her from succumbing to these temptations, Devon says as she sits with a group of other women in the Rutgers Recovery House’s lounge. One is that “this place is always open,” even during breaks. The other: Students who relapse are required to move out.

Students here say they hold each other accountable and are quick to notice when a dormmate is struggling. When Devon was tempted to relapse recently, she went to her friends and told them, “Don’t let me.” And when Cherise had anxiety attacks during finals week, she says, a fellow recovering student, Jen, sat with her and helped her breathe.

Most students aren’t so fortunate. On a vast majority of campuses, those in recovery still face an impossible choice: “Return to the same environment that fed my problem, or prioritize my health and forgo my education,” says Amy Boyd Austin, president of the Association of Recovery in Higher Education.

Barriers to more programs

Advocates say there are two reasons there aren’t more programs: money and stigma.

When money is tight, many colleges prioritize prevention and response, investing their limited dollars in efforts to stop substance abuse and treat it when it occurs. Many remain focused on the much more pervasive problem of marijuana and alcohol abuse. In the University of Michigan survey, nearly two-thirds of students said they had been drunk at least once in the previous 12 months, and almost 40 percent said they had used marijuana — the highest rate since 1987.

The stigma surrounding drug and alcohol addiction is subsiding as students become more open about their struggles, advocates say. But it’s far from gone. Many college leaders continue to say they don’t have recovering addicts on their campuses, a claim made easier by the lack of reliable data on addiction rates among college students.

“Most schools are still in denial,” says Kristen Harper, a consultant with Transforming Youth Recovery.

Often it takes a tragedy to spur a college into action. But Mr. Freeman, of The College of New Jersey, says that even if the numbers of students who would benefit from recovery programs is small, it’s an investment worth making.

“For the students who are involved with them, they’re absolutely life-changing,” he says. “If we don’t pay now to help people recover and lead productive lives, we will pay later.”

Cherise, who started down the path to addiction when she was just 11, says she probably wouldn’t have made it through college without the recovery house. She says she “learned how to be part of a family” in the dorm.

“This is a priceless place,” she says. “There’s unconditional love.”

This story about drug treatment and recovery for college students was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

S. Sudan’s midwives, lifted by aid, wonder how long donors will deliver

Donors understandably want to make good investments – to put their money where it will work. This piece looks at what that means in a place like Africa’s youngest nation, whose ambition is up against a perception by some outsiders that it’s close to a lost cause.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When South Sudan became independent in 2011, the country had just a few professionally trained midwives. Eight of them, to be precise. Donations flooded in to help the world’s youngest country deliver its youngest citizens safely. “Every day the quality of care was getting better. Every day we could do more than the day before it,” says Dr. Alice Pityia. But over the past five years, civil war has severely tested the world’s altruism here, as aid delivery grows more expensive and more dangerous and looters raid facilities. In maternity wards like Dr. Pityia’s, many employees wonder how much longer donations will keep coming for a place that seems, in many ways, to keep falling apart. But turning their attention elsewhere isn’t an option. When midwife Judith Draleru ran out of gloves during a delivery, she slipped plastic bags over her hands and carried on. Sometimes she works by the light of candles mothers have brought themselves. “Every day, despite all our challenges, you see that you are saving mothers and you are saving babies, so how can you stop?” she says. “I am the commander in chief of these babies’ lives.”

S. Sudan’s midwives, lifted by aid, wonder how long donors will deliver

It was July 9, 2011, and just outside the walls of the maternity ward at the largest public hospital in the city, a country was being born.

Inside, meanwhile, babies were also being born, lots and lots of babies.

As Dr. Alice Pityia scrambled through her rounds, the wails of the newest citizens of the world’s newest country mixed with the cheers of the crowd outside. Throughout the delivery ward, mothers sprawled on the thin metal beds talked names.

Independence, she heard one suggest. Yes, that was a good name for a girl. Elegant and strong.

Salva Kiir, offered another, after the man who had been their president for all of 20 minutes.

“You have never seen mothers so happy,” says Dr. Pityia, remembering her shift at the Juba Teaching Hospital that Saturday, the day South Sudan became independent from Sudan.

But medical staff, too, were hopeful. South Sudan was now on the map – literally and metaphorically. That meant faraway governments were suddenly ready to cut big checks in the name of making life better in the world’s youngest country. In scrappy maternity wards like the one in Juba, where power flickered on and off and nurses frequently asked patients to buy gloves and needles, money poured in.

“Every day, the quality of care was getting better. Every day, we could do more than the day before it,” says Pityia. The maternity ward where she worked was renovated, and next to it, the country’s first neonatal intensive care unit sprung up, full of incubators and tiny cradles. South Sudanese doctors and nurses who had scattered around the globe began returning, ready to work.

Then came the fighting.

Since 2013, a civil war has severely tested the strength of the world’s altruism here, making South Sudan one of the most expensive places to deliver aid, and one of the most dangerous. Over the past five years, global donors have given an average of more than a billion dollars annually to South Sudan, most of it for short-term humanitarian assistance.

“The cost of doing business here has become enormous,” says Mary Otieno, the South Sudan country representative for the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). “All of this creates a lot of uncertainty and therefore donors are not willing to invest in the long term.”

In maternity wards like Pityia’s, many began to worry for the future. They still do. How much longer, they wonder, will the donors with fat checkbooks keep caring about South Sudan before they simply give up? How long can you convince the world to keep giving to a place that seems, in many ways, to keep falling apart?

Momentum, dashed

When South Sudan became independent, many donors immediately turned their attention to its health system, which had been decimated by five decades of conflict. They were particularly concerned with one statistic: Of every 100,000 women who gave birth in South Sudan, more than 2,000 died. It was one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world – about 150 times the rate in the United States, and more than 500 times the rate in Finland at the time. Fewer than 1 in 5 women had a trained professional to assist them when they gave birth.

Funders pledged money to train midwives – the country had only eight at independence – and kit out health facilities. South Sudanese doctors and nurses returned to quite literally deliver their country its next generation.

“I felt like, let me come do this for my country,” says Pityia, who had grown up in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan. And anyway, the money wasn’t bad – she made 4,000 South Sudanese pounds, then around $2,000, a month.

But in December 2013, less than 2-½ years after she celebrated independence day in the maternity ward, forces loyal to South Sudan’s president, Salva Kiir, clashed with the troops of its vice president, Riek Machar. The conflict quickly spiraled into a full-blown civil war. Oil production – the source of 95 percent of government revenue – ground to a halt.

As South Sudan’s government struggled to keep pace with its bills, it began printing more money, tanking the value of the currency. (Today, Pityia’s monthly pay is worth around $30, and she makes most of her money doing consulting on the side in private clinics.) Nurses and midwives, paid even less than the doctors, began hassling patients for cash. Next, the hospital began to run out of medicine, then basic supplies.

Across the country, meanwhile, forces on both sides attacked and looted clinics. By 2016, half the medical facilities in the country had been destroyed, according to government estimates.

Even in Juba, the capital, women often died giving birth at home at night because they were afraid to cross notoriously dangerous government checkpoints to reach nearby hospitals. By 2016, the government estimated that only 9 percent of women were giving birth with the help of a doctor or midwife in a health facility.

'Commander in chief of these babies' lives'

Still, at the Teaching Hospital in Juba, the staff did what they could. Judith Draleru, a Ugandan midwife working for UNFPA, rallied her colleagues to help clean the wards, since the cleaners, whose salaries were now worth only a few dollars a month, had mostly stopped showing up to work. When a patient needed blood, Ms. Draleru asked her friends to donate, or she did it herself. When there were no gloves available to assist with a delivery, she slipped plastic bags over her hands and carried on, sometimes working by the light of candles the mothers had brought themselves.

“Every day, despite all our challenges, you see that you are saving mothers and you are saving babies, so how can you stop?” she says. “I am the commander in chief of these babies’ lives.”

But for many others, the question is flipped – without money, without supplies, without support, how long will it be possible to go on?

At the Teaching Hospital, the next potential casualty is an ambitious midwife training program. Since 2012 the program – which is funded by the Swedish and Canadian governments – has trained more than 600 midwives here, and scattered them across the country.

“What we’ve done so far is just a drop in the ocean, so we are hopeful the program will find a way to continue,” says Ms. Otieno of UNFPA, which runs the midwife training course. “But there will not be a new first year class next year unless we get another donor.”

Like many here, she’s hopeful that a recent peace agreement will bring enough stability to convince donors they can fund long-term projects here. Hopeful that after seven years, the world is not yet ready to give up on South Sudan.

But for the South Sudanese themselves, forgetting about this place has never been an option. “If we leave, this country doesn’t have a future,” says Pityia, shrugging. All her life, she says, she was waiting to have her own country. Now that she does, she isn’t about to leave it.

Across town, meanwhile, in a tiny clinic in the Gumbo neighborhood, Draleru is helping train a group of traditional birth attendants – a kind of catch-all term for the women neighbors know to call when one of them goes into labor. Together, the attendants practice basic hygiene: washing their hands and snipping umbilical cords with clean, sharp razors. These trainings are essential, Draleru says, because most mothers never make it to a hospital.

“Why do I keep doing this? Because you cannot say no to a woman in your community who needs you,” says Brigina Wasuk, one of the students, who has been delivering babies for more than a decade in her Juba neighborhood. “It’s not an option for us.”

Silvano Yokwe contributed reporting. Support for the reporting of this story was provided by the International Women’s Media Foundation.

In California, sheltering the chinook salmon after pushing it to brink

Here’s a silver-lining story. Drought focused attention on river health in California. That led to an awakening around the plight of a native species – and then to collaboration on helping to heal its habitat.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Levees, dams, farming, and other factors have devastated the population of the California coastal chinook salmon over the last century. Today a broad coalition of public officials, farmers, fishing operators, and conservationists are working on salmon recovery programs along the Sacramento River where the fish spawns. One of those springs from an idea that Dave Vogel, a fisheries scientist, had two decades ago: an underwater salmon shelter. Last year 25 six-ton shelters were installed in the river. Each consists of tree limbs or root wads bolted to a limestone boulder. Vogel’s design recreates the salmon’s natural habitat, much of which has been lost, and provides a refuge from predators for the ocean-bound juveniles. The $600,000, three-year pilot project, which is largely privately funded, is the first of its kind in the country. “The old attitude was ‘It’s going to take 100 to 200 years for nature to heal itself,’ ” Vogel says. “Now the attitude is ‘Let’s start solving one problem at a time.’ ”

In California, sheltering the chinook salmon after pushing it to brink

Dave Vogel already knew that levees and dams had devastated the coastal salmon population in California’s longest river. The surprise for the fisheries scientist arrived when he saw the video footage of young salmon clustered beneath bridges in the watery depths.

City and county agencies in Northern California hired Mr. Vogel to provide research on several bridge-construction and retrofit projects along the Sacramento River starting in the late 1980s. He surveyed the riverbed with radar and underwater cameras to gauge the potential impact of the bridge work on the California coastal chinook salmon, whose population has plummeted since the turn of the 20th century.

Prior studies found that juvenile salmon gravitated to the river’s shoreline for protection. Vogel’s videos instead revealed a fish tale of desperate adaptation born of the loss of habitat. The young chinook take refuge some 20 feet below the surface behind bridge piers and other artificial barriers, an imperfect alternative that still exposes them to bass, trout, and other predators.

The footage gave Vogel an idea. Dams prevent tree debris from flowing downstream, depriving young fish of cover from predators and the swift current. He envisioned recreating the salmon’s habitat in deep water to help the fish mature and grow stronger, improving their odds of surviving to make the 300-mile migration to the Pacific Ocean.

Last year, two decades after that inspiration, tugboat crews installed 25 salmon shelters in the river near Redding, Calif., 160 miles north of Sacramento. Each six-ton shelter consists of large almond tree limbs or walnut root wads bolted to a massive limestone boulder. The protruding boughs and roots create a kind of maze that allows juvenile salmon to evade bigger fish and the current’s constant pull.

River Garden Farms, a family-owned, large-scale farm based on the river, invested $400,000 in the shelters and obtained a $200,000 federal grant for the three-year pilot project, the first of its kind in the country. The shelters count as one of dozens of projects planned, ongoing, or completed on the Sacramento River since the Northern California Water Association (NCWA) launched a salmon recovery program four years ago that builds upon earlier efforts.

“The old attitude was, ‘It’s going to take 100 to 200 years for nature to heal itself,’” Vogel says. “Now the attitude is, ‘Let’s start solving one problem at a time.’”

From drought grows cooperation

The US Fish and Wildlife Service listed the California coastal chinook salmon as threatened in 1999, five years after the Sacramento River’s winter run of the species received endangered status. The 447-mile-long river sustains four annual salmon spawning cycles — the only waterway in the world to hold that distinction — on the strength of its depth, food supply, gravel floor, and year-round cold temperature.

The winter salmon count has plunged from 25,000 in the late 1970s to 1,500, and the mortality rate of eggs, hatchlings, and juvenile salmon has reached as high as 95 percent in recent years.

But the effects of levees and dams, coupled with the ravages of climate change, agriculture, and development, imperil more than the river’s winter run. A report last year warned that almost half of California’s native species of salmon and trout in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta and other major waterways could die off within 50 years.

Proposed solutions for restoring the salmon population have abounded for decades. Since an update to the delta’s water plan in 2000, the state has added tons of spawning gravel at various sites for female salmon to lay eggs and installed protective fish screens near dams and intake pipes.

The pace of progress quickened during a five-year drought starting in 2012 that sharpened concerns over the river’s health among public officials and the agriculture and fishing industries. The collective sense of urgency has enabled the NCWA to bring together a broader coalition for salmon conservation.

“The drought forced people out of their silos,” says Roger Cornwell, general manager of River Garden Farms, a 15,000-acre operation that relies on river irrigation to grow corn, rice, walnuts, and other crops. “The collaboration we’ve seen to help the salmon is the drought’s silver lining.”

Many of the Sacramento River projects shepherded by the association draw on a 2011 report authored by Vogel, who runs an environmental sciences consulting firm in Red Bluffs, Calif. He dropped his radar into the river last summer and again earlier this year and detected thousands of young salmon huddling around and flitting through the salmon shelters.

He will collect data and video over the next two years that could persuade public officials to extend and expand the project. In the meantime, he welcomes the eagerness of nonprofits and farm operators after years of inertia from government agencies in response to salmon depletion.

“These outside groups are much more ready to take calculated risks and use adaptive management,” Vogel says. He recalls the initial skepticism of state and federal biologists to the idea of salmon shelters. “They said, ‘We know that’s not going to work.’ Well, give us a chance to try.”

David Guy, president of the NCWA, regards the new spirit of cooperation as crucial to the salmon’s survival given that the most obvious answer to their plight — removing levees and dams — stands little chance of happening.

“We spent the last hundred years confining salmon,” he says. “Now we need to spend a hundred years unconfining them, so to speak, and that means working with each other and trying new things.”

A fish vs. farms truce?

The California Natural Resources Agency announced a plan last year to save three endangered species of fish in rivers and tributaries in the Central Valley watershed. The list includes the winter run of the chinook salmon in the Sacramento River, and the state’s strategies for restoring fish habitat and 6,000 acres of floodplains parallel concepts nurtured by the NCWA’s recovery program.

The idea to reestablish floodplains mirrors a project launched by the association last year that Mr. Guy hopes will cool the “fish vs. farms” conflict pitting environmentalists against the agriculture industry. Farmers complain that the state, attempting to preserve fish ecosystems, allows surplus river water to funnel toward the Pacific Ocean at the expense of crop irrigation.

The NCWA effort could demonstrate that restored floodplains serve the needs of fish and farmers alike. Scientists are working with farmers to flood rice paddies along the river to create simulated wetlands. When the farmers later drain their fields, the water carries added nutrients back to the river, aiding the growth of juvenile salmon preparing for the long journey to the San Francisco Bay and out to sea.

The flow of water replicates the cycle that existed before levees, dams, and development eliminated 95 percent of the region’s floodplain wetlands, and as the water level drops in the fields, farmers can plant crops. “They get to have their water and keep it, too,” says Peter Moyle, associate director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at the University of California, Davis.

Center researchers devised an earlier study in which they flooded part of a rice field bordering a river bypass between Sacramento and Davis. The water formed a temporary marsh that provided a refuge for young salmon to rest and feed, gaining size and strength far from predators before returning to the river.

The ephemeral wetlands, like the salmon shelters, represent small steps toward reversing more than a century of manmade devastation inflicted on the chinook salmon. Scientists caution that solving the crisis will require at least a generation or two even under ideal circumstances.

On the other hand, Moyle says, “It’s pretty clear what happens if we don’t do anything.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The best way to curb illegal migration

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Of all the migrants apprehended along the Southwest border of the United States so far this year, some 43,000 – the largest share – have come from Guatemala. The mass exodus from that country will end only when its people can elect a government that reflects their values, enabling the kind of trust and integrity that can prevent corruption and violence. Guatemala seemed to be heading down that path. Three former presidents as well as dozens of lawmakers, judges, and drug traffickers have been convicted by emboldened prosecutors. This success was part of decade-long effort driven by popular sentiment and a special United Nations-sponsored investigative body. In the past year, however, the country has started to backslide. Among his other moves, President Jimmy Morales has started to bring out the military to intimidate his opponents. Guatemala’s future now rests on tapping the people’s values. Recent anti-corruption protests in the capital are a signal of a new awakening, one that demands good governance. As a recent World Bank report about developing countries put it, “The idea of power cannot be understood without taking seriously the power of ideas.”

The best way to curb illegal migration

Of all the migrants apprehended along the Southwest border of the United States so far this year, some 43,000 – the largest share – have come from Guatemala. Stemming that flow will require more than a big wall or stiffer penalties for illegal entry.

As recent events in Guatemala show, the mass exodus from the Central American country will end only when the people there can elect a government that reflects their values, enabling the kind of trust and integrity that can prevent corruption and violence.

In recent years, Guatemala seemed to be heading down that path. Three former presidents as well as dozens of lawmakers, judges, and drug traffickers have been convicted by emboldened prosecutors. This success was part of a decade-long effort driven by popular sentiment and a special United Nations-sponsored investigative body, known as CICIG for its initials in Spanish.

In 2015, a new president, Jimmy Morales, was elected on an anti-corruption platform. Guatemala, along with Argentina, had become a model in Latin America in how to start eroding a culture of impunity among the political elite and military.

A poll last year found 70 percent of Guatemalans support CICIG. In addition, the murder rate fell from a high of 45 people per 100,000 in 2009 to 26.1 in 2017. The country also saw an improvement in the rate of homicide cases solved. The people began to trust their justice system.

In past year, however, the country has started to backslide. After the CICIG began to investigate President Morales and his brother and son, Guatemala fell into a constitutional crisis. Morales defied the country’s Constitutional Court in his attempt to stop the CICIG’s work. This month, he prevented the head of the UN commission, Iván Velásquez, from returning to the country after a visit to the US.

Morales has also started to bring out the military to intimidate his opponents. The move is a throwback to military rule during a decades-long civil war that ended in 1996. And his supporters in the legislature are now trying to pass measures to back him up.

What matters in this crisis is that Guatemalans be allowed to express their values. The country will elect a new president in June. Morales will not be able to run again. Thelma Aldana, a popular former attorney general who led many of the prosecutions, could become the next president.

Guatemala’s future now rests on tapping the people’s values. As a recent World Bank report about developing countries put it, “The idea of power cannot be understood without taking seriously the power of ideas.”

In Argentina, with its own faltering path against corruption, a recent poll found 72 percent of individuals regard family values or individual principles as the key factors motivating them to act with integrity in the professional environment. A much smaller percentage cited legal regulations or codes of conduct. “Values and culture are critical enablers of trust and integrity, both in the short and long term, to reinforce behavior,” stated the survey’s report, which came from the World Economic Forum’s Partnering Against Corruption Initiative.

The flow of Guatemalans to the US border is only a symptom of a deeper need in that country. Recent anti-corruption protests in the capital are a signal of a new awakening, one that demands good governance based on the people’s own views about integrity in public life.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Sheltered ‘under the shadow of the Almighty’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

Today’s column points to the comfort, safety, and peace God imparts to all His children.

Sheltered ‘under the shadow of the Almighty’

He who dwells in the secret place of the Most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty. I will say of the Lord, “He is my refuge and my fortress; my God, in Him I will trust.” … He shall cover you with His feathers, and under His wings you shall take refuge.

– Psalms 91:1, 2, 4, New King James Version

Step by step will those who trust Him find that “God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble.”

– Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 444

In heavenly Love abiding,

No change my heart shall fear;

And safe is such confiding,

For nothing changes here.

The storm may roar without me,

My heart may low be laid;

But God is round about me,

And can I be dismayed?

Wherever He may guide me,

No want shall turn me back;

My Shepherd is beside me,

And nothing can I lack.

His wisdom ever waketh,

His sight is never dim;

He knows the way He taketh,

And I will walk with Him.

Green pastures are before me,

Which yet I have not seen;

Bright skies will soon be o’er me,

Where darkest clouds have been.

My hope I cannot measure,

My path in life is free;

My Father has my treasure,

And He will walk with me.

– Anna L. Waring, “Christian Science Hymnal,” No. 148

A message of love

Shore is crowded

A look ahead

Thanks for exploring with us today. Tomorrow we’ll have the first of two stories examining this question: For survivors of child sexual abuse by priests, coaches, and other trusted figures, what would justice look like?