- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Compassion in a time of coronavirus

In today’s edition, our five selected stories cover Amy Klobuchar’s voter appeal, privacy versus safety in Brazil, the rise of a four-day workweek, fewer suicides in Latvia and Lithuania, and signs of progress worldwide.

The coronavirus story, to date, has mostly been a narrative of fear and rising, faceless numbers. But for Hong Kong-based journalist Yuli Yang, this is personal. She grew up in Wuhan, China. Her parents are OK, but struggling with three weeks of quarantine and the death of a friend.

Last week, Ms. Yang was “looking for a way to send beams of light into that darkness.” First, she published a “love letter” highlighting her hometown’s lakes, spicy noodles, and local hero, Li Na, a tennis star. The Wuhan vignettes were her effort to “open up a small space ... a space for compassion ... to support ... my fellow Wuhaners.”

Then, Ms. Yang organized a digital “get well soon” card on Twitter. “The people of Wuhan are fighting this virus and they need us ... so that we can all heal, collectively,” she told CNN Friday. The global response was swift and mostly inspiring.

“For those of you who have the virus, for those of you who are waiting and waiting ... you are not alone. We do care about you! We are praying for you. For strength, for healing, for peace ... Sending lots of love! #GoWuhan,” posted Celia Evenson, a French woman in Russia.

Ms. Yang translated and posted the notes on Weibo, a Chinese website. In one small corner of the internet, she is shattering the walls of isolation and indifference, sending light and love to the people of Wuhan.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In chill of New Hampshire, signs Klobuchar is warming

What does a surge by the senator from Minnesota tell us about the New Hampshire electorate? It suggests a desire for pragmatism, Midwestern values, and yes, a sense of humor.

At a time when many Democrats are sounding Eeyorish, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar is cracking jokes and winning over voters by telling them, “I know you, and I will fight for you.” After months or polling in the single digits, she is wriggling out of her stiff senatorial shell and had moved into third place ahead of Tuesday’s New Hampshire primary.

Her late surge may reflect a yearning for civility – and a calculation that the best way to beat President Donald Trump is to field a candidate who can woo back white working-class Midwesterners and disaffected Republicans. “I think she’s a healer,” says former state Rep. Sally Kelly of Chichester, New Hampshire, who grabbed a front-row seat at a Klobuchar rally in New Hampshire this weekend, where up to 100 people were still waiting to get in after the event was scheduled to start.

But Senator Klobuchar, despite having passed four times as many bills as the average Democratic senator, and running a modest campaign on far fewer donations than any of the other front-runners, faces an uphill battle in the bigger states that will soon follow.

In chill of New Hampshire, signs Klobuchar is warming

“My plan,” vows Sen. Amy Klobuchar, putting on her best Trumpian air, “is to build a beauuuuuuuutiful blue wall … and make Donald Trump pay for it!”

That wall, she tells the cheering crowd in Salem, New Hampshire, will be made up of Democrats, independents, even moderate Republicans. Together, they will prevent President Trump from sweeping key battleground states – a category she extends to New Hampshire. And indeed, there are plenty of swing voters here, a state where Hillary Clinton won by fewer than 2,800 ballots.

“Amy speaks to my sensibilities more than anybody,” says David Liddy, a lifelong Republican and retired naval officer who changed his party affiliation to vote in Tuesday’s primary, though he retains conservative views. “She seems to be very dedicated, very hardworking.”

As the granddaughter of an iron ore miner who has consistently won over Minnesota’s rural voters – including in 2018, when she emerged victorious in 42 counties that had gone for Mr. Trump two years earlier – Senator Klobuchar came down the homestretch in New Hampshire with arms wide open for the state’s independents and disaffected Republicans like Mr. Liddy.

Until Friday, there was little evidence that she was getting much traction. Now, after a strong debate performance, she’s the buzziest candidate. And at the 11th hour, she seems to have wriggled out of her stiff senatorial shell and is showing audiences a warm, even funny side.

As other Democrats sound increasingly Eeyorish, Senator Klobuchar is buoyant, cracking jokes about the president’s complaint that his cameo was cut from Home Alone II (“Who does that?”) and alluding to his cancellation of a Denmark trip after the prime minister rebuffed his interest in buying Greenland.

It seems to be working. Multiple polls showed her in third place in New Hampshire, edging ahead of Sen. Elizabeth Warren and former Vice President Joe Biden. At Klobuchar rallies over the weekend, attendance far exceeded the expectations of her campaign. In Manchester Saturday, staffers had to ask attendees to stand so their chairs could be removed to make room for more people.

Democrats are split over whether they want a progressive champion who will push for sweeping change, or a centrist figure who can right the ship. They’re also uncertain about whether the best way to beat Mr. Trump is with a candidate who excites the base or one who could woo back white working-class Midwesterners.

The “Klomentum” is clearly driven by voters who subscribe to the latter theory, some of whom have been casting around for another option after Mr. Biden finished a disappointing fourth in Iowa despite leading in national polls for much of the past year.

“You have Trump skating through the impeachment, his big State of the Union speech – and I think Democrats are saying, ‘How do we beat this guy?’” says Andrew Smith, director of the University of New Hampshire Survey Center in Durham. Pete Buttigieg is seen as too young and inexperienced, he says. Bernie Sanders, they worry, will get hammered as a socialist. And Joe Biden is flaming out. “People are saying, ‘What’s left?’” says Dr. Smith. “And she’s left.”

A scrappy campaign

Like most pundits and pollsters, Dr. Smith didn’t see her placing better than third in New Hampshire, despite the fact that independents – who comprise 40% of registered voters here – could vote in the Democratic primary. Rather than becoming the nominee, the thinking goes, she may just seriously hurt both Ms. Warren and Mr. Biden, further splintering the Democratic field. Then again, few expected her to get this far when she announced her candidacy a year ago in Minneapolis, standing on the banks of the Mississippi in the middle of a snowstorm, arguing she was the one with the necessary grit to beat Donald Trump and bridge “the river of our divides.”

“The thing that is critical to me is healing the country,” says former Democratic state Rep. Sally Kelly of Chichester, New Hampshire. “I think she’s a healer.”

Those who have known her for decades say that is born out of experience, including loving her father throughout his battle with alcoholism.

“I think there’s a lot of forgiveness and empathy in her ability to do that,” says longtime friend Kate Herrmann Stacy, who was a bridesmaid in Ms. Klobuchar’s wedding. “When we were in law school, I would react quickly and conclude, ‘Oh, that person is such a jerk.’ She was kinder and more forgiving and would have a better sense of why they might be acting that way.”

Despite gaining a reported $4 million in donations since Friday’s debate, Senator Klobuchar may not be well-positioned to capitalize on a strong showing in New Hampshire when the race moves on to the larger states of Nevada and South Carolina. She has raised barely a quarter as much as Senator Sanders – $28.7 million compared with his $107.9 million – and less than half of the three other front-runners. She doesn’t even make it into the top 10 in terms of Democratic campaign spending so far.

In New Hampshire, Senators Sanders and Warren already had around 75 staffers on the ground when the Klobuchar campaign hired its third staffer last spring. Thanks to the endorsements of three state newspapers, including the traditionally conservative Union Leader, and talking with thousands of voters at Rotary clubs or local restaurants over plates of poutine, she managed to stay alive even as other, flashier candidates dropped out.

“Think of what she has accomplished, to be where she is in this campaign with the resources she has,” says Michael Atkins, a Peterborough lawyer who was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 2008 and 2004. An early endorser of Senator Klobuchar, he says 90% of people he talks with after her rallies walk away sold.

“We’ve run a scrappy campaign,” says Karen Cornelius, a New Hampshire retiree who has been volunteering full time for the past year to help her former law school classmate get elected.

‘I know you’

One silver lining to her relative lack of campaign resources is that it reinforces her image as fiscally responsible.

She routinely pulls up to election rallies in nondescript rental cars – not the big SUVs with tinted windows favored by some other candidates. After one of her first TV appearances, her friend Ms. Stacy texted to compliment her on the teal jacket she was wearing. I got it on sale! $29.95, Ms. Klobuchar wrote back.

On Monday, as her modest campaign was enjoying its biggest moment yet in the media spotlight, that was the jacket she chose to wear.

“She’s low-key, she’s not flashy at all,” says Richard Leland, a California Republican waiting in line for a Biden event with five fellow Republicans, all of whom say the Republican Party has turned its back on fiscal conservatism. All say they’d vote for Senator Klobuchar “in a heartbeat” over President Trump.

Last week, the head of the Concord Coalition, a nonpartisan organization calling for fiscal responsibility, singled out Senator Klobuchar as the only presidential candidate “with an express goal of lowering the debt-to-GDP ratio.” At a time when other Democrats are proposing massive increases in government spending, her plan calls for establishing a $300 billion fund, seeded with an increase in the corporate tax rate, “to make a down payment to tackle the U.S. debt and protect our economy” – and help reduce the annual budget deficit, currently projected to exceed $1 trillion.

“If she sticks with that, she’ll get a lot of Trump supporters,” says David Marti, a Trump voter whose son brought him to see Senator Klobuchar this weekend in hopes of persuading his dad to vote for a Democrat.

When Senator Klobuchar arrived in New Hampshire at 4 a.m. last week with the Iowa caucus results still unclear, Ms. Cornelius heard a new line in her stump speech.

The senator, who has been reading historian Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book on presidential leadership, related a story from the days following President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death. As the train carrying his body caused a man watching to break into tears, a reporter asked, Sir, did you know the president?

No, the man replied. But he knew me.

Senator Klobuchar has lately adapted that line, presenting an image for voters that is far different than one created by a series of negative articles last spring criticizing her exigent approach as a boss.

“If you have trouble stretching your paycheck to pay for that rent, I know you, and I will fight for you,” she said in her closing remarks at the debate. “I’m asking you to believe that someone who totally believes in America can win this, because if you are tired of the extremes in our politics and the noise and the nonsense, you have a home with me.”

Staff writer Story Hinckley contributed to this report.

Brazil takes a page from China, taps facial recognition to solve crime

We look at why the fight against violent crime is leading many Brazilians to sacrifice their personal privacy in the quest for safety.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Ana Ionova Contributor

Ester Clenilda’s Rio de Janeiro neighborhood could become the latest testing ground for Brazil’s experiment in fighting staggering crime with high-tech surveillance, like facial recognition. She’s supportive, even if weary about being watched.

“I will be calmer knowing that they’re looking for the criminals,” Ms. Clenilda says.

Far-right President Jair Bolsonaro was elected in large part on his vow to give police more power to crack down on soaring violence. Cities and states across the country are mulling bills that would allow or even mandate surveillance technology in public spaces and Mr. Bolsonaro recently signed decrees that aim to create a centralized database of citizens’ personal and biometric information.

Despite enthusiasm, for some, the government’s approach harks back to Brazil’s military dictatorship, which leaned heavily on surveillance to target opponents. In China, an unrivaled state surveillance apparatus has had a chilling effect on political expression and personal freedoms. It also happens to be the country providing Brazil with the bulk of its surveillance technology.

Brazil takes a page from China, taps facial recognition to solve crime

Ester Clenilda is not comfortable with the idea of police watching her every move. Yet she still welcomes a new project that could see officers hunting down criminals in her neighborhood with facial-recognition cameras mounted on their uniforms.

“It’s a good thing,” says Ms. Clenilda who sells headphones, small gadgets, and cables at a tidy electronics stall in Rocinha, one of Brazil’s largest favelas. “People will have peace of mind. I will be calmer knowing that they’re looking for the criminals.”

Rocinha is a jumble of cinder-block homes stacked high above some of Rio’s wealthiest beachfront neighborhoods. After a stretch of relative calm, Rocinha is suffering renewed violence as gangs battle each other and the police. It could become the latest testing ground for Brazil’s broader experiment in fighting staggering crime with high-tech surveillance.

While in much of the world citizens are increasingly speaking out against mass surveillance and digital invasions of privacy, Brazil appears poised to embrace them in the name of security.

The government is yet to hold a public hearing on the use of such surveillance, but Brazil’s far-right President Jair Bolsonaro was elected in large part on his vow to give police more power – digital and otherwise – to crack down on crime. Now, cities and states are mulling a patchwork of bills that could mandate crime-fighting technology, like facial recognition cameras, in public spaces. Mr. Bolsonaro recently signed a pair of decrees that aim to create a vast, centralized database of personal and biometric information on Brazil’s more than 200 million citizens.

Some fear the government’s new approach harks back to Brazil’s repressive 1964-1985 military dictatorship, which leaned heavily on surveillance to weed out opponents. And some of the clearest risks of this technology are already visible in China, where an unrivaled state surveillance apparatus has had a chilling effect on political expression and personal freedoms.

“If you look at the history of facial recognition, it is often developed – first and foremost – to prevent dissent,” says Maya Wang, a senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch. “These systems developed to perpetuate inequality rather than securing public safety.”

Intelligence vs. brutality

In Brazil, the push for security solutions comes against a grisly backdrop of violent crime, both at the hands of gangs and police. Mr. Bolsonaro has played into citizen exasperation with violence, vowing that criminals will “die like cockroaches in the streets.” He proposed legislation that would allow police and civilians to shoot suspected offenders without fear of persecution, in addition to his more high-tech surveillance ideas.

The increased desperation for solutions has pushed Brazilians to embrace the promises of state surveillance, says Christian Perrone, a senior researcher on rights and technology at the Institute for Technology and Society of Rio de Janeiro. Although crime has fallen since hitting a record high in 2017, Brazil still logged more than 57,000 homicides in 2018.

“People are not as aware of what they are giving up. But they understand very well the crime and security side that affects their lives every day,” says Mr. Perrone, adding that privacy is a price many feel they must pay for security.

For Ocimar Santos, a Rocinha resident and community leader, the hope is that the new approach will lead to smarter and more targeted policing, replacing the chaotic and bloody shootouts that often occur between gangs and authorities in Rio’s favelas. The number of deaths at the hands of police was at an all-time high in Rio last year: Police killed an average of five citizens per day, and the city averaged 20 shootouts per day last year.

“The way things have traditionally been done puts the life of the common citizen at risk,” Mr. Santos says. “Anything that uses intelligence instead of the brutality” is preferred.

The context in Brazil is starkly different from many other parts of the world like Europe and North America, where governments – under mounting pressure from civil society – are considering banning facial recognition tools. Several U.S. cities, like San Francisco, have already outlawed their use, citing concerns about accuracy and potential abuse by law enforcement.

An appealing market for China?

Much of Brazil’s push toward mass surveillance appears inspired – and made possible – by China, home to some of the world’s biggest manufacturers of this technology. For Chinese companies, Brazil represents a huge market with special appeal.

There are millions of cameras monitoring citizens across China, though experts say their accuracy is far from perfect, especially when implemented in less homogenous countries like Brazil.

“Brazil is actually a strategic point ... because of our cultural diversity,” says Mr. Perrone. “When you train in such a diverse, multicultural place, you’re actually training your artificial intelligence to be smarter and more accurate.”

Soon after President Bolsonaro took office last year, several senators from his party were invited on a free trip to China to learn about its surveillance work. At the time, they said they were inspired by China’s use of facial recognition systems and, in August, one lawmaker introduced a bill that aims to make the technology mandatory in all public spaces.

China has already sold some of this surveillance equipment to other countries in Latin America, a potentially vast and lucrative market with by high crime. Out of the 20 nations in the world with the highest homicide rates, nearly all are in Latin America. Ecuador implemented a far-reaching surveillance system using Chinese technology. A province in northern Argentina began using Chinese facial recognition technology last year.

“China’s market for mass surveillance has grown so much that the companies are really benefiting from it,” Ms. Wang says. She says the ease of selling in this market is appealing, but there are perks for the Chinese government as well: “The intention is also to build a world that is friendly to the Chinese Communist Party.”

Chinese surveillance is already leaving its mark on Brazil. In late 2018, the city of Campinas, in Sao Paulo state, started a pilot using Huawei facial recognition cameras with the aim of “replicating” the company’s “advanced public safety” model for smart cities.

The program in Campinas uses artificial intelligence to collect and comb through a database of biometric information, personal data, and social media images. When artificial intelligence identifies a wanted suspect, the system alerts nearby authorities via mobile phone, allowing them to make an arrest quickly.

The same Huawei technology has been used in the northeastern state of Bahia on an even wider scale. Police credit the program for 118 identifications of wanted criminals as of mid-January. Huawei has also strategically partnered with Brazilian telecommunications giant Oi to commercialize facial recognition technology in the country.

Facial recognition surveillance is being tested in Rio de Janeiro, where technology from Oi and Huawei was used during Carnaval last year and the Copa America soccer final. The technology passed the “first test drive” and police say it will be implemented on a wider scale.

Last month, authorities announced they plan to mount 200 cameras on police patrolling Rocinha, with images sent to a control center running facial recognition software.

Is it working?

There is no “compelling evidence” that this technology improves safety, Ms. Wang from Human Rights Watch says. Mr. Perrone fears it could simply push crime outside the boundaries monitored by cameras.

Critics warn that unchecked use of such high-tech tactics like facial recognition without legal protection already in place could have far-reaching implications, allowing companies to amass and potentially misuse a vast trove of personal information. Although Brazil passed a data protection law in 2018 set to create a supervising authority and a legal framework for how personal data is handled, it won’t take effect until August. Last year, a leak revealing personal information like social security numbers and names of family members of about 20 million people in Ecuador – which does not yet have a data protection law – put some of these risks in sharp relief.

“In many parts of the world, facial recognition is new and so legislators are literally just catching up,” in terms of protection measures, Ms. Wang says. “In this vacuum, it’s easy for surveillance companies to move in.”

Comic Debrief

Four-day workweek: Why idea of shorter hours gains support

The 40-hour workweek has been U.S. law for eight decades. But now, worldwide, there’s a nascent effort to boost productivity by working fewer hours. Is less, more?

In 1930, British economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that, a century hence, rising productivity would shrink the average workweek to just 15 hours. Needless to say, his prediction was a bit off.

But maybe Keynes’ ideas weren’t as far-fetched as they sound. A growing number of businesses are experimenting with a four-day, 32-hour workweek, with mixed success. Microsoft’s Japan subsidiary tried it in the summer of 2019, and reported a 40% boost in worker productivity. But when the Portland, Oregon, tech education company Treehouse tried it in 2015, the CEO remarked that the reduced working hours killed his “work ethic.”

Since then AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka proposed a “leisure dividend” to compensate workers for their increased productivity. The 2019 manifesto of Britain’s Labour Party advances a similar proposal.

Would a four-day, 32-hour workweek actually work? Many business owners, concerned with foreign competition, remain skeptical. But many workers’ advocates and environmentalists say it would be a change for the better. Even some historians, like Dutch author Rutger Bregman, say that the three-day weekend is an idea whose time has come. – Eoin O'Carroll, staff writer

Latvia and Lithuania begin to tackle a chronic scourge: suicide

Thanks to shifting attitudes about treating mental health, suicide rates are dropping. But prevention and education efforts are still at an early stage.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Lithuania and Latvia may be success stories for their post-Soviet economy and political trajectories, but they are still struggling to overcome another Soviet legacy: high suicide rates. The two countries rank among the highest in the world for death by suicide, due in large part to the Soviet-era stigma attached to mental illness and seeking help for it. But authorities in both countries have started to make modest headway against that longstanding reluctance toward treatment.

Lithuania had 24.4 deaths by suicide per 100,000 population in 2017, the world’s highest rate, with Latvia not far behind with 18.1 per 100,000, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. This is a marked improvement for Lithuania. In 2013, the country had a suicide rate of 31.9 per 100,000.

“Over the last few years, the entire field of suicide prevention has become much more active in Lithuania, particularly in Vilnius,” says Paulius Skruibis, a psychologist at Vilnius University. “We have extensive gatekeeper training. We have policies in place to decrease alcohol consumption.”

Ilze Viņķele, the Latvian minister of health, is also considering a number of measures to both destigmatize psychotherapy and make it more available to younger Latvians. “We are at the beginning of the road,” she says.

Latvia and Lithuania begin to tackle a chronic scourge: suicide

Latvia and Lithuania are two of the most westernized of the fifteen former Soviet republics, with robust economies and relatively sound democratic political systems.

Unfortunately, both countries share a less happy distinction when it comes to suicide. While they have made considerable progress in overcoming their global-high rates of suicide, significant obstacles remain. Perhaps the most stubborn is the stigma attached to mental illness and seeking help for it, a vestige of the Soviet era. But more recently, authorities in both countries have started to make modest headway against a longstanding reluctance to treat mental illness, including suicidal or potentially suicidal patients.

“The good news is that we have the lowest suicide mortality rate ever,” says Toms Pulmanis, vice dean of faculty in the school of public health at Rīga Stradiņš University, referring to the situation in Latvia. “The bad news is that our suicide rate is still amongst the highest in the world.”

“Yes, suicide rates are decreasing,” says Paulius Skruibis, a psychologist on the staff of Vilnius University, and one of the small, dedicated group of Lithuanian suicidologists. “But obviously we have a long way to go.”

Challenging old beliefs

Lithuania had 24.4 deaths by suicide per 100,000 population in 2017, the world’s highest rate, with Latvia not far behind with 18.1 per 100,000, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

This is a marked improvement for Lithuania in just a handful of years. In 2013, the country had a suicide rate of 31.9 per 100,000.

“Somehow suicide has become part of the Lithuanian story,” Vaiva Klimaitė, a psychologist at Vilnius City Mental Health Center told the Monitor in 2015.

That year, several hundred Lithuanians lay down in the capital’s Cathedral Square in a widely publicized protest over the lack of progress fighting suicide. That, along with the alarm raised by mental health professionals and increased attention from the media, spurred officials to start publicly addressing the issue.

“Over the last few years, the entire field of suicide prevention has become much more active in Lithuania, particularly in Vilnius,” says Dr. Skruibis. “We have a lot happening,” he adds. “We have extensive gatekeeper training. We have policies in place to decrease alcohol consumption.”

In April 2016, the mental health center established a new department of suicide prevention. Also, Vilnius initiated its first comprehensive suicide strategy, though Dr. Skruibis says that “We still need to scale it up to the national level.”

Antanas Grizas, the founder of Youth Line, a psychological outreach program, acknowledges the positive changes, at least on the municipal level, but feels there is a lack of attention from the national government. “I still see the Ministry of Health as presenting the situation as much less dangerous than it is.”

As in Lithuania, the tight-knit community of suicidologists and suicide prevention professionals in Latvia say the biggest obstacle to improving the country’s mental health and bringing the suicide rate further down are the persistent, regressive Soviet-era attitudes regarding suicide and mental health in general.

“During the Soviet time, people who opposed the system were often put in psychiatric clinics,” says Zane Avotiņa, director of Skalbes, a suicide prevention clinic and help line based in Riga. “That’s one of the reasons why people at risk are still reluctant to seek help.”

Another problematic legacy of the Soviet era, says Ms. Avotiņa, “is that many people can’t accept that depression is actually an illness. They think that people who are depressed are just lazy. ... There is a belief that adults should deal with their emotions and feelings by themselves.”

“Beginning of the road”

Ilze Viņķele, the Latvian minister of health, says she is trying to change that. “Suicide is one of the most extreme indicators of mental health,” she says, “and one which reflects many other factors, including the social and economic health of the country, as well as the culture of public interaction.”

Under Ms. Viņķele’s leadership the government has already taken a number of steps designed to both improve and expedite treatment for Latvians who are at risk of taking their lives.

“We are making progress in raising the profile of mental health,” says Elmārs Rancāns, the head of the psychology department at Rīga Stradiņš University. “New patient facilities are being opened. And multidisciplinary teams – not just doctors and nurses, but others, such as physical therapists – are becoming involved.”

In the meantime Ms. Viņķele is also considering a number of measures to both destigmatize psychotherapy and make it more available to younger Latvians, including developing free online cognitive behavioral therapy, as well as creating a dedicated mental health tent for music festivals.

“We are at the beginning of the road,” Ms. Viņķele says.

Points of Progress

Where neighbors help each other fight foreclosure

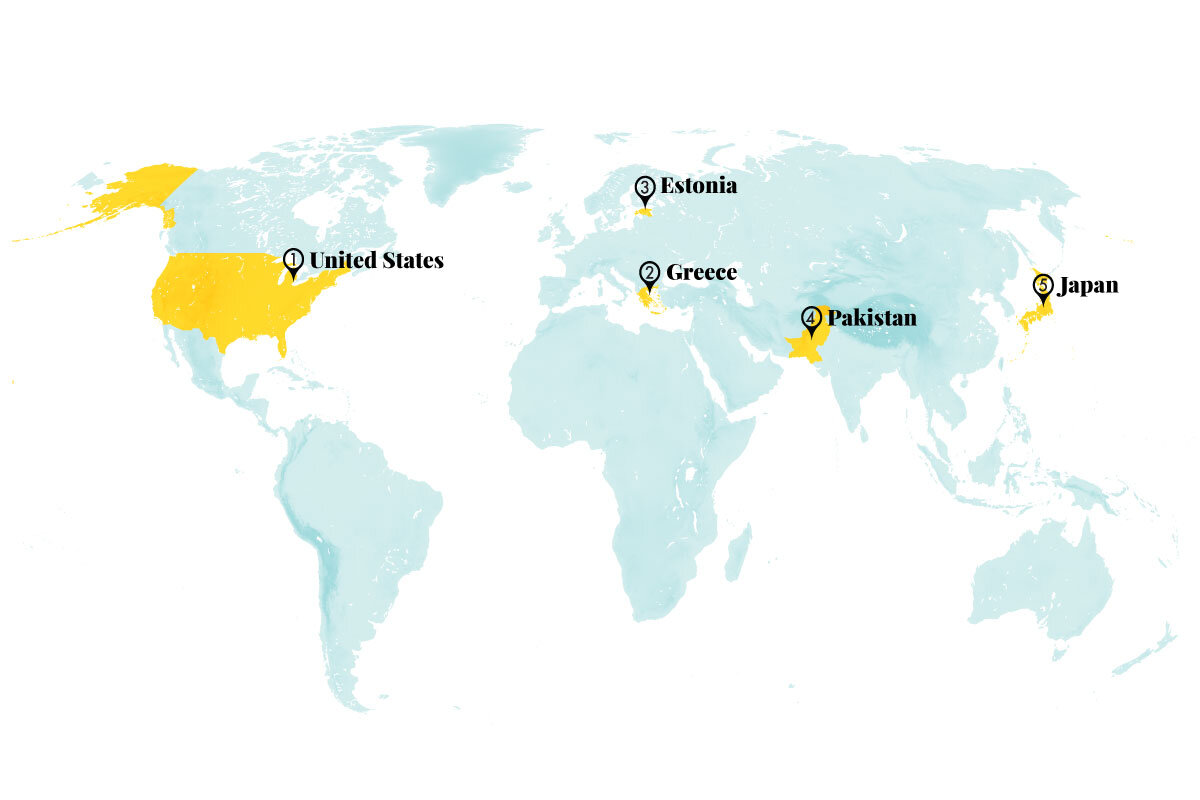

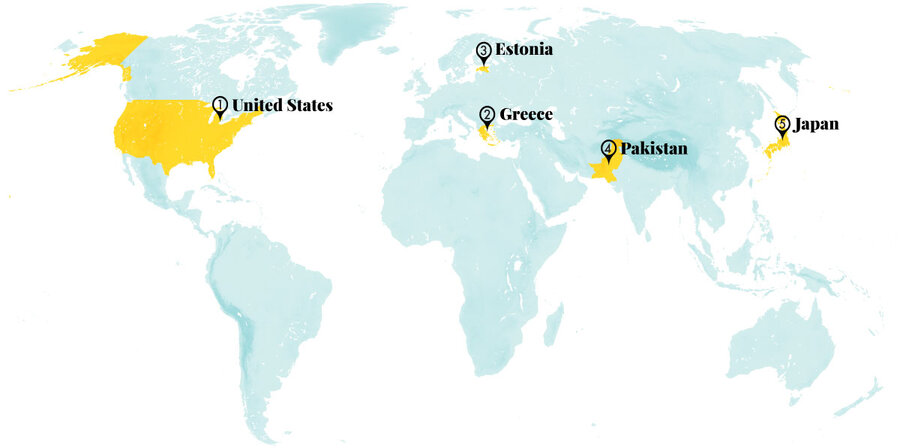

We find progress busting out in five places around the world, including gender equity in Greek leadership and in box office receipts, the judiciary checking Pakistani military reach, and using radar to protect Japan’s forests.

Where neighbors help each other fight foreclosure

1. United States

To prevent their neighbors from facing foreclosure, around 450 people are going door to door in Detroit – helping more than 4,300 families keep their homes in 2018 alone. Neighbor to Neighbor, the program organizing the door-knocking, provides property tax information with a human touch for almost all of the city’s at-risk residents, who may not be aware their home could be seized because of unpaid taxes. With some of the country’s highest property taxes and lowest average property values, Detroit experiences exceptionally high rates of home loss. Since its founding in 2017, Neighbor to Neighbor has contributed to the city’s near-90% reduction in tax foreclosures since a peak in 2015. (Thomson Reuters Foundation)

2. Greece

Greece elected its first female president on Jan. 22, a sign of hope for gender equality in one of Europe’s more conservative countries. The left-leaning Katerina Sakellaropoulou, a high-court judge and human rights advocate, was confirmed by 261 out of 300 members in Greece’s parliament. Though the position is largely ceremonial, she has said environmental protection will be her main focus when she assumes the presidency in mid-March. “Today a window to the future has opened,” says Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis. “Our country enters the third decade of the 21st century with more optimism.” (The Guardian)

3. Estonia

In its five years of existence, Estonia’s e-residency program, which gives non-Estonians digital access to some of the country’s business services, has brought the state’s economy more than €31 million ($34 million) of income in the form of taxes and fees. From Seoul to St. Petersburg the program’s 60,000-plus participants have founded more than 10,000 companies. The money generated by the e-residency program directly benefits Estonian citizens, says manager Ott Vatter, funding education, culture, and social welfare programs. (The Baltic Times)

4. Pakistan

As Pakistan’s armed forces increase control over the country’s government, the national judiciary has, through a series of recent rulings, interrupted a seeming drift toward martial law. By holding former military members to account and checking recent actions by the military it deemed illegal, the court has asserted its judicial independence, which has at times been in doubt. The rulings come as Pakistan’s military extends its influence over a weak democracy, ostensibly restored to civilian rule in 2008. “The court is providing a message to the armed forces that they should remain within the four corners of the constitution,” says Rasheed Rizvi, former president of the Supreme Court Bar Association. (The Wall Street Journal)

5. Japan

The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization has agreed to use data from a powerful Japanese radar system to more closely monitor and protect forests and train governments to do the same. No matter the weather, the radar can track forests around the world 24 hours a day, allowing the FAO to easily detect deforestation and fire hazards. This improved ability will enable the U.N. agency to enhance the monitoring capabilities of countries with large forests, such as Indonesia and Congo, increasing their chances of attracting funding to support further conservation efforts. (Thomson Reuters Foundation)

Worldwide

After rising almost 10% from 2018 to 2019, the share of top grossing films featuring female protagonists is now almost the same as those with male protagonists, according to research from the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film. In 2019, films with female protagonists made up 40% of the total number, whereas those with male protagonists and ensemble casts accounted for 43% and 17% respectively. The relative parity of the percentages suggests major gains for women in the film industry, especially since the share of female leads is a recent high. Meanwhile, the total percentage of women as major characters and speaking characters remained relatively stable, with each under 40%. (Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film)

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why Iraq’s youthful protests endure

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Iraq’s capital of Baghdad was carpeted with a rare snowfall Tuesday. It brought people onto the streets in a collective experience that was an apt reflection of the past four months in Iraq. Since Oct. 1, tens of thousands of young people have maintained nonviolent protests in major cities, hoping to redefine the meaning of community for Iraq.

The protesters seek a secular state that respects civic rights and an end to a type of government in which power and oil wealth are divvied up by religious and ethnic groups. Such aims are similar to those raised during months of protests in nearby Lebanon. Because of Iraq’s pivotal position in the Middle East, its protests may be the most significant of the many youthful protests that erupted worldwide in 2019 from Chile to Algeria to Hong Kong. If one element binds these movements, it is the rejection of how governments have been organized and an embrace of inclusive democracy.

A new meaning of community may be forming in Iraq, one that could reshape a troubled region. Like a blanket of snow, young Iraqis are bringing a country together in a way it rarely experiences.

Why Iraq’s youthful protests endure

Iraq’s capital of Baghdad was carpeted with a rare snowfall Tuesday. It brought people onto the streets to make snowmen together and join in friendly snowball fights. The collective experience was an apt reflection of the past four months in Iraq. Since Oct. 1, tens of thousands of young people have maintained nonviolent and leaderless protests in major cities, hoping to redefine the meaning of community for Iraq. So far, despite the killing of more than 500 demonstrators, neither the protesters nor their shared vision has melted away.

With nearly half of Iraqis under age 21, the protesters are as difficult to ignore as are their idealistic aims. They focus on creating a secular state that respects civic rights and an end to a type of government in which power and oil wealth are divvied up by religious and ethnic groups. They also want foreign powers (namely Iran and the United States) to stop meddling in Iraqi affairs.

Such aims are similar to those raised during months of protests in nearby Lebanon. In both countries, the uprising has led to the downfall of a prime minister and an uneasy tension with the political elite over who will run government. In Iraq, the protesters have a powerful ally, the revered Shiite cleric Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani. He has called for an end to the killing of protesters and for free and fair elections “as soon as possible.” A new government, he says, must earn the people’s trust.

Because of Iraq’s pivotal position in the Middle East, its protests may be the most significant of the many youthful protests that erupted worldwide in 2019 from Chile to Algeria to Hong Kong. If one element binds these grassroots movements, it has been the rejection of how governments have been organized and an embrace of inclusive democracy based on universal principles.

In a speech Monday, Achim Steiner, administrator of the United Nations Development Program, described this global trend in its broadest meaning:

“From the grassroots, to the business communities, to people voting with their feet in protest, mature democracies and autocracies alike are experiencing a new form of community today – a new form of people power – representing a profound shift in the global landscape of collaboration and dissent. ...

“We once thought of a community as a group of people who live in the same geographic area, or who share socio-economic, ethnic, linguistic, or religious characteristics. The evolving global context, including the extent to which new technologies have empowered communication and information-sharing at the individual-level, requires us to embrace a far wider definition.

“Many communities that drive change now cut across the boundaries of class, geography, language, religion, political orientation, and identity. They do not ‘respect’ the typologies of the past.

“What binds them together is shared experience, understanding, belief, and common visions and ways of working.”

His explanation helps justify the close attention to the protests in Iraq. A new meaning of community may be forming, one that could reshape a troubled region. Like a blanket of snow, young Iraqis are bringing a country together in a way it rarely experiences.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The ‘influencer’ our world most needs today

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

There are many influences out there, digital and otherwise, some beneficial and others corrosive. But each of us can contribute to a happier, healthier, and more just world by welcoming the all-embracing influence of God, good.

The ‘influencer’ our world most needs today

Nowadays, many people have become well-known “influencers” simply by cultivating an online presence. Some of this influence is beneficial. Yet our online time can also be very distracting, or worse still, a corrosive influence.

Of course, negative influences aren’t new. As a New Yorker piece pointed out, “Influence was worrisome long before it was digital” (Laurence Scott, “A History of the Influencer, from Shakespeare to Instagram,” April 21, 2019).

Whether dispersed digitally or otherwise, adverse influences need to be counteracted, and we can each play a role in accomplishing this. For instance, when tempted to be influenced by intense polarization, we can dial down animosity by dialing up the impartiality of our love.

Referring to the timeless commandment to love our neighbor as ourselves, Jesus notably put no limit on who qualifies as that neighbor. He also pinpointed the need to “love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you” (Matthew 5:44).

This guidance goes well beyond managing our outward behavior, as vital as that is. Our thinking has an influence on others, for better or for worse. Like a stone thrown into water, the thoughts we harbor create ripples, which are often felt by others even if these thoughts are not expressed in words or actions.

We recognize this most keenly in the impact our changing moods can have on friends and family. But humanity is another family we belong to, and depending on our mental standpoint, we pour into the ocean of universal human consciousness anything from evil thinking that pollutes to spiritual thoughts that help purify.

So being alert to what kind of thinking we entertain is a way of loving our neighbors near and far. In particular, we can listen for thoughts from the divine Mind, God. They come to us through Christ, God’s message of our true spiritual goodness as God’s creation, made in the spiritual image of the Divine. As such, we are never weak and vulnerable but reflect a strength that is incorruptible, not prone to manipulation.

The influence of recognizing this was illustrated by the impact it had on Jesus’ neighbors. Healing and character transformation resulted, indicating the potential for our understanding of this same idea to be an influence for good today.

We might feel we’re just taking baby steps in understanding this healing idea of our true identity. Yet the willingness to seek this healing, reforming understanding is invaluable. And every glimpse of God’s all-embracing influence that throws spiritual light on the lives of others is also bringing to light the true nature of the glimpser, because we are all reflections of the one divine Mind. As Jesus’ healings proved, limitations such as disease and despair that seem so real to materially based thinking yield to the understanding of divine Love’s infinite influence, bringing to light a spiritual harmony forever known to God and always available to all of us.

Thoughts that lead us away from God’s love, distract us from expressing that love, or even persuade us we are sick, sinful, or stuck in an inescapable victimhood are mental impostors. When we hold to our real being as divine Mind’s reflection, we more readily identify and see through those impostor thoughts. Then divine reality is uncovered in individual healing.

There’s also a wider impact as we conscientiously yield to the one Mind, as highlighted by Mary Baker Eddy when teaching the Christian Science she had discovered to a class. Referring to the perfection of creation revealed in the Bible’s book of Genesis, she said, “We, to-day, in this class-room, are enough to convert the world if we are of one Mind; for then the whole world will feel the influence of this Mind; as when the earth was without form, and Mind spake and form appeared” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” pp. 279-280).

This doesn’t denote a desire to convert anyone to a particular religious denomination. Rather, it signifies a yearning to help overcome the false paradigm of life in matter through recognition and demonstration of divine Love’s overarching influence.

Whether or not we have a public calling, we can contribute to a happier, healthier, and more just world. Daily devotion to entertaining the “influencer” humanity most needs – the Christ-idea – is a great way to help realize that goal.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Jan. 27, 2020 issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

High water

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about what our sun can teach us about finding planets in other solar systems.