- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Super Tuesday: Which candidate does Russia want to win?

- After US deal, Afghans see long road to peace. Still, they hope.

- Two new reasons not to avert your eyes from the Syria crisis

- US Marines lead charge in rooting out racism in military ranks

- From Sudan to low-Earth orbit, accountability finds footholds

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Super Tuesday: Where you’ll always find Violet

Today’s five selected stories cover Russian motives in undermining voter trust, what fuels Afghan hope for peace, a search for compassionate solutions in Syria, the U.S. Marines’ battle with racism, and a global roundup of credible progress.

The word “democracy” derives from Greek words, demos (people) and kratia (power).

But when it comes to exercising people power, Americans don’t have a stellar record. The last time voter turnout topped 60% was five decades ago. It fluctuates, but only about 55% of the voting age U.S. population has participated in recent presidential elections.

Voter participation in the first four 2020 primary and caucus states has been good but not great for Democrats. But Republicans have had record turnouts, reports Rolling Stone, suggesting an engaged Donald Trump base.

Every four years, Americans have the duty and privilege of choosing a leader to champion their hopes and values. That’s why it warmed my heart when a Monitor colleague told me about his 18-year-old son’s first trip to the ballot box. On Tuesday morning, the whole Kaplan family went to the Joseph P. Manning Elementary School in Jamaica Plain, a neighborhood of Boston.

They voted, and they met Violet, an engaging 101-year-old woman checking addresses. She’s been a volunteer for the democratic way for “decades,” says my colleague. After loading up on scones and banana bread at the adjacent bake sale, Asher Kaplan proudly slapped the “I voted” sticker on his jacket.

We’ll begin to see the results of this kind of carbohydrate-fueled people power when Super Tuesday polls start to close at 7 p.m. ET. Look for our report in Wednesday’s edition.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Super Tuesday: Which candidate does Russia want to win?

Russian interference has less to do with picking a candidate than it does with undermining trust in American democracy and sowing divisions, say U.S. intelligence officials.

Does Russia have a preferred candidate in the 2020 U.S. election? There’s not yet enough hard evidence to know for sure, though on Monday U.S. intelligence agencies confirmed that foreign influence campaigns continue to spread “false information and propaganda.”

Any preference is likely to be more utilitarian than ideological, seeking someone who acts as a vehicle for broader Russian foreign policy goals, which include undermining American democracy. Populists tend to be particularly useful to this end, becoming a divisive wedge thanks to their anger.

Facebook in October removed 50 Instagram accounts, 11 of which were supporting President Donald Trump and four praising Sen. Bernie Sanders. But as a whole, the accounts, which appeared to be part of a network, were working to fuel divisions by posting on opposite sides of controversial issues such as police violence.

“They’re fueling both sides of the argument, because what they want to do is bring the two sides to a clash,” says Heather Conley of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, speaking of the broader Russian strategy. She frequently tells audiences: “The American mind is the battle space.”

Super Tuesday: Which candidate does Russia want to win?

Is Russia working to reelect Donald Trump, the unorthodox real estate magnate turned president? Is it also seeking to elevate Sen. Bernie Sanders, who as a democratic socialist mayor of Burlington, Vermont, established sister cities in Nicaragua and the Soviet Union?

Or is its preference simply the candidate through whom it can create the most chaos?

As voters headed to the polls Tuesday in 14 states from Texas to Tennessee, questions like these are overhanging the entire election. On Monday, U.S. intelligence agencies and federal departments issued a rare joint statement warning that foreign influence campaigns continue to spread “false information and propaganda.”

So what does Russia really want?

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a country run by a former KGB operative, the answer is complicated.

First of all, it’s not clear to what extent Russia is influencing American voters online. As social media companies and intelligence agencies bolster their efforts to prevent large-scale disinformation campaigns, Russia is trying to fly under the radar.

Second, to the extent that Moscow may be trying to boost a particular candidate, it’s more utilitarian than ideological. Yes, it would like someone whose policy views align with Russian interests, but it is also looking for the best wedge to divide the American people.

“It’s about finding vehicles to support their broader foreign policy goals,” says Jessica Brandt, head of research and policy at the German Marshall Fund’s Alliance for Securing Democracy in Washington. Those goals, she adds, include sowing chaos in a way that “spikes doubt, distracts us, polarizes us, and divides us.”

Indeed, in a broader sense, Russia wants exactly what America is giving it – a country so polarized that it is easy for a foreign interloper to masquerade as yet another angry citizen and exploit those divides even further. And because the nation is so divided, it can’t even agree on the nature of the threat. National efforts to get to the bottom of the mischief and prevent further meddling are viewed by some with distrust, preventing a strong united response.

“Intelligence briefings and warnings are now being used as a cudgel to score political points – not protect the country,” says Heather Conley, director of the Europe Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington and co-author of “The Kremlin Playbook: Understanding Russian Influence in Central and Eastern Europe.” “This is where I see Mr. Putin sitting back, his feet on his desk, and his work here is done.”

Is Russia seeking to boost Trump, Sanders?

Long before Vladimir Putin ascended to the Russian presidency or Mr. Trump had any hope of winning a U.S. election, the Kremlin was looking for candidates and officials in adversarial countries who could work from within to boost Moscow’s interests. That was part of the old Soviet playbook, says Clint Watts, an ex-FBI agent who began tracking Russian disinformation campaigns targeting the U.S. in 2014.

At the start of the 2016 cycle, the main thrust of Russia’s influence operations was a very focused effort to undermine former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, whom President Putin believed was behind opposition protests in Russia.

Then a new theme emerged, says Mr. Watts: “This Donald Trump guy would be great for us, and he’s hyperdivisive.”

Russia also looked favorably on Sen. Bernie Sanders, who back when he was the democratic socialist mayor of Burlington, Vermont, had visited Cuba and Nicaragua.

According to a 2018 indictment, social media specialists involved in the 2016 Russian meddling were instructed to “use any opportunity to criticize Hillary and the rest (except Sanders and Trump – we support them).”

Why? Populists tend to act as a divisive wedge because they’re so passionate and angry, says Mr. Watts. That feeds into Russia’s goal of making American democracy look dysfunctional, undermining the world’s faith in U.S. leadership and weakening alliances that Russia sees as opposing its own interests.

“Their long-run goal is break up NATO, break up the EU, advance their position around the world, and lower America on the world stage so there’s more space for them to elevate themselves,” says Mr. Watts.

Russia is reportedly again seeking to boost both President Trump and Senator Sanders, who was briefed by intelligence officials on the matter, according to the Washington Post. The Vermont senator denounced any Russian attempts to undermine American democracy, calling President Putin “an autocratic thug.”

“My message to Putin is clear: Stay out of American elections, and as president I will make sure that you do,” Mr. Sanders said.

Mr. Trump, for his part, has called the reports of Russia aiding his reelection campaign “disinformation.”

Cracking down on Russian disinformation

In Monday’s joint statement, the heads of the Departments of State, Justice, Defense, and Homeland Security, as well as three intelligence agencies and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) cited an “unprecedented level of commitment and effort to protect our elections and to counter malign foreign influence” and warned of “sharp consequences” for any foreign powers who dared meddle.

CISA is working with all 50 states and more than 2,300 local jurisdictions to secure the country’s election systems, including free vulnerability scanning and onsite risk assessments. The FBI is working with social media companies, which have invested significantly in election integrity efforts.

Indeed, there is far more alertness now than in 2016, says Ben Nimmo, a pioneer of disinformation investigations.

He notes that one of the most prominent fake accounts in that election cycle, @TEN_GOP, was registered to a Russian mobile number. That wouldn’t fly today – and the Russians likely wouldn’t try it, either. They’re increasingly trying to hide their efforts, says Mr. Nimmo, director of investigations for Graphika, a company that bills itself as the cartographers of the internet age.

For example, some 50 Instagram accounts taken down by Facebook in October used almost no original text, instead copying and pasting from other accounts so as to avoid small grammatical mistakes that would give them away as non-native English speakers. But that has made it hard to build a persona, limiting their reach. Of these accounts, only one had more than 20,000 followers, according to a Graphika report co-authored by Mr. Nimmo.

The accounts taken down included 11 supporting Mr. Trump and four supporting Mr. Sanders. But as a whole, the accounts, which appeared to be part of a network, were working to fuel divisions by posting on opposite sides of controversial issues such as police violence. Some included hashtags like #blacklivesmatter or #policebrutality while others would use #bluelivesmatter or #backtheblue.

“They’re fueling both sides of the argument, because what they want to do is bring the two sides to a clash,” says Ms. Conley of CSIS, who frequently tells audiences: “The American mind is the battle space.”

How polarization muddies the waters

If foreign information operations are like fish swimming in the sea, hyperpartisanship has created hospitable waters for them to swim in, says Mr. Nimmo.

In that environment, he says, voters should be alert to efforts to manipulate them through emotion – whether it’s coming from Russia or a fellow American.

“If I see a post which is trying to make me angry or afraid, maybe I should ask why it’s trying to do that,” he says.

After all, it’s not just Russians posting polarizing content online. If there hadn’t been American trolls back in 2016, there wouldn’t have been anyone for the Russians to pretend to be.

And it’s not just social media; TV and talk radio also contribute to a polarized media ecosystem. Still, there’s a qualitative difference in the threat posed by Russian disinformation – which could sow doubts about the legitimacy of election results.

“Foreign trolls are a small percentage of it,” says Renée DiResta, technical research manager at the Stanford Internet Observatory, who coauthored a report for the Senate Intelligence Committee quantifying and analyzing Russia’s influence operations targeting U.S. citizens from 2014-17. “The challenge is that their presence is potentially used to discredit the results of an election and suggest that outsiders are tampering, which is why continuing to detect that is such an important thing.”

If there is a contested Democratic convention this summer, Mr. Watts says Russia would almost certainly exploit that by pushing the notion that the system was rigged against Mr. Sanders. That’s a narrative Russia very effectively fed when its military intelligence unit hacked into Democratic National Committee emails and leaked documents showing the party establishment’s preference for Mrs. Clinton. This year, Mr. Sanders’ supporters could be even more angry if they suspect the nomination was stolen from them.

It’s not hard to envision “everybody going to the convention and screaming at each other,” says Mr. Watts. “And Russia clapping, because this is exactly what they wanted.”

So what is the answer?

“Both parties have to love the country more,” says Ms. Conley – even if it means forgoing an opportunity to score political victories. “You have to love the country more than your own power.”

After US deal, Afghans see long road to peace. Still, they hope.

Hope is powerful and resilient. Our reporter talks to Afghans, no strangers to violence and uncertainty, about their cautious optimism, even as the U.S.-Taliban peace deal stumbles out of the gate.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

U.S. officials heralded the landmark deal reached with the Taliban Saturday as a “monumental” step toward ending America’s longest war. But the conditional, step-by-step process spelled out in the document, signed with such fanfare Saturday in Doha, Qatar, is very specific on the withdrawal of “all foreign forces,” while very vague on how intra-Afghan talks will reconcile sworn enemies.

Indeed, the day after the signing, President Ashraf Ghani – whose government was left out of the U.S.-Taliban negotiations – rejected the release of Taliban prisoners in exchange for government detainees held by the Taliban, which the deal requires. In response, the Taliban announced Monday it would resume operations against Afghan security forces.

“In the book that’s written about the peace process that hopefully ends and resolves the 40 years of conflict in Afghanistan, [the Doha deal] is the prologue. This isn’t even Chapter 1,” says Andrew Watkins, an Afghanistan analyst.

“Everyone wants peace, and we are hopeful for this deal,” says the manager of a Kabul wedding hall wounded in a Taliban bombing that killed more than a dozen people. “All Afghans are happy,” he says. “But we don’t know our future.”

After US deal, Afghans see long road to peace. Still, they hope.

The modest Khorshid Party Hall, damaged in a September bombing, has been rebuilt with the same ingredients Afghans are now applying to the landmark U.S.-Taliban withdrawal deal signed Saturday: a measure of hope, and a heavy dose of caution.

It was a Taliban suicide attack on a checkpoint near this hall in downtown Kabul that killed an American and more than a dozen others and prompted President Donald Trump to abruptly end nearly a year of closed-door talks with the Taliban as they were on the cusp of a deal.

Today this wedding venue has been repaired – its bouquets of fake flowers restored, its small glass chandeliers rehung – with the hope that weddings and spending will flourish once again, if intra-Afghan talks due to start March 10 yield a long-term peace.

But after sweeping up the glass smashed by the Sept. 5 blast, builders replaced it with plywood – hidden by curtains and wallpaper – as a precaution, in case this peace effort fails to stop the war in Afghanistan, and explosions resume.

U.S. officials heralded the deal, which followed a seven-day reduction in violence, as a “monumental” step toward ending America’s longest-ever war, with an initial drawdown from some 12,000 to 8,600 U.S. troops by May.

But the conditional, step-by-step process spelled out in the four-page document, signed with such fanfare Saturday in Doha, Qatar, is very specific on the withdrawal of “all foreign forces” in 14 months, while very vague on how intra-Afghan talks will reconcile sworn enemies with opposing worldviews.

Indeed, the day after the signing, President Ashraf Ghani – whose government was left out of the U.S.-Taliban negotiations – rejected the release of 5,000 Taliban prisoners, in exchange for up to 1,000 government detainees held by the Taliban, which the deal requires before March 10.

In response, the Taliban spokesman announced Monday that the reduction in violence was over, and that the insurgent group would resume “normal” operations against Afghan security forces – though not U.S. targets.

As a result, many Afghans are tempering their hope, and recognize that the heavy lifting to end conflict here has barely begun.

“Everyone wants peace, and we are hopeful for this deal,” says Mohammad Najib Nasrat, manager of the wedding hall, who still bears a deep shrapnel scar on his leg from the explosion.

“Not only us – all Afghans are happy,” he says. “But we don’t know our future.”

No cease-fire in deal

That uncertainty has only been amplified by the U.S.-Taliban deal for many Afghans, who were surprised to read that a “permanent and comprehensive cease-fire” – in a war that has been killing and wounding 10,000 civilians a year since 2014 – is no more than an agenda item in talks between the Taliban and “Afghan sides.”

The deal does not name the official U.S.-backed government of President Ghani, which the Taliban dismisses as illegitimate, but which will by necessity lead a team at intra-Afghan talks.

And the jihadist force that the U.S. ousted from power in 2001, in the weeks following the 9/11 attacks, is described elliptically in the text as “the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan which is not recognized by the United States as a state and is known as the Taliban” – a legitimizing nod to Taliban insistence that they be called by the name of their former Islamist government.

The Taliban are repeatedly sending messages to their estimated 80,000 fighters that the withdrawal deal marks a victory for them, and the surrender of a superpower.

Taliban chiefs in Pakistan have also been sending voice messages encouraging fighters to kidnap local officials, to increase leverage for a prisoner exchange.

By sundown in Wardak Province alone, the Taliban stronghold southwest of Kabul, officials reported that three policemen and 55 civilians had been kidnapped.

Agreement as prologue

“In the book that’s written about the peace process that hopefully ends and resolves the 40 years of conflict in Afghanistan, [the Doha deal] is the Prologue, this isn’t even Chapter One,” says Andrew Watkins, senior analyst for Afghanistan for the International Crisis Group.

The deal is the culmination of a difficult, 18-month process, he notes, and the two opposing Afghan sides have yet to even sit down at the same table.

In terms of global conflict resolution, from that point of face-to-face talks onward, it took four years to achieve peace in Colombia, and became multi-year processes in both the Philippines and South Sudan – despite far weaker insurgencies in every case.

Analysts and Afghans alike note that colossal, even existential issues remain, from the shape of any interim government and final power-sharing structure, to the mechanism to possibly integrate Taliban fighters and Afghan security forces after years in which the insurgents portrayed their enemy as infidels.

“This deal doesn’t guarantee anything. ... It is very, very conditional,” says Mr. Watkins. “The U.S. government has written [it] in a way that allows them to cancel all of this withdrawal, if they are uncomfortable or unsatisfied with the Taliban’s behavior at any point.”

And while President Trump has made clear his desire to end the 18-year American war in Afghanistan, the Taliban have sent mixed messages.

On one hand, the Taliban since last year began referring less to the government as a U.S. “puppet,” and instead say “Kabul administration.” Shortly before signing the deal Saturday, Taliban leaders staged a small parade in Doha with a conciliatory message.

“For them to speak to their followers, in their most victorious moment of this conflict ... one of the first things out of their mouths is, ‘Brothers, don’t be inflammatory, don’t taunt your Afghan brothers, don’t use this as a chance to pick a fight,’” says Mr. Watkins. “That’s an interesting message, that’s new language.”

Deal is with U.S., “not Afghans”

On the other hand, a Taliban spokesman stated Sunday that the insurgents struck a deal with the U.S. alone, “not Afghans.” That suggested that the Taliban have changed little, especially to those in Kabul supportive of the U.S.-backed government, which has overseen years of significant progress in women’s rights and civil society.

“That was confusing us. We were just worried about what that means: Are they going to harm Afghan forces, or the nation, again?” asks Mina, a twenty-something who works at the Afghan Finance Ministry and would only give her first name.

“For decades we were kept away from education and from our basic rights, especially women were so harmed. ... Unfortunately since childhood we have those dark memories,” says Mina, who wears turquoise nail polish and a headscarf that slips off while she talks.

“As a citizen of this country, of course we are all striving for peace. [The deal] was again making me happy and giving me strong feelings [of] a brighter future,” she says.

But the text makes no mention of preserving women’s rights, about access to education, or not wearing the all-enveloping burqa – all issues the Taliban strictly forbade when in power in the late 1990s.

Other issues abound. For the government, Mr. Ghani was only last week declared to have been reelected in a September vote, but his main challenger disputes the result, leading to disunity – and therefore a weaker hand – among the political elite, says Fawzia Koofi, a former lawmaker and the first woman head of an Afghan political party, the Movement for Change in Afghanistan.

The Taliban also must control fighters who may prefer war over peace.

“I think it will give them zero credibility, if [the Taliban] continue to respect their agreement with the Americans but fight with Afghans,” says Ms. Koofi, who twice met with Taliban leaders in Moscow in the past year.

“Some of these Taliban are born and grow up fighting. ... Their weapons give [them] a life and identity,” she says. “How do you distance them from that identity, how do you bring them back to normal life? That is an opportunity, but that is a challenge.”

Patterns

Two new reasons not to avert your eyes from the Syria crisis

Caught in the middle of the geopolitical clash in northern Syria are as many as a million civilians fleeing the fighting. Who will protect them? At stake are long-standing humanitarian principles.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Never has it been more important to resist the impulse to cover our eyes about Syria.

Hundreds of thousands of civilians are confronting a no-holds-barred offensive by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in the Idlib region. And his forces, backed by Russian air power, have targeted civilian areas, schools, hospitals, and aid facilities.

The civilians are trapped. Huddling in makeshift dwellings in the cold, they’re being pushed toward a border that Turkey has sealed. But they are trapped in another way as well: by a tug of war over Syria’s future.

Russia, which supports Mr. Assad, and Turkey, which backs insurgents, are at odds. Turkey is pressing NATO and the European Union to side with it. But President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has alienated NATO by trying to play it off against Russia. Largely missing are the United States and Britain.

That absence has had two important ripple effects. The first cleared the way for Russian military involvement that rescued Mr. Assad. The second weakened any credible Western opposition to a wholesale violation of rules protecting noncombatants. A key question now is whether the U.S. and the Europeans seek to reengage.

Two new reasons not to avert your eyes from the Syria crisis

It’s being described as the final chapter in Syria’s devastating civil war, but that’s by no means certain. And never, since the conflict began nine years ago, has it been more important to resist the impulse to simply cover our eyes.

The immediate reason is what’s happening on the ground. Hundreds of thousands of civilians are bearing the brunt of a no-holds-barred offensive by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to subdue the last major pocket of rebel resistance, in the northwest region of Idlib. The onslaught began late last year. Mr. Assad’s forces are backed by Russian mercenaries, Iran and its Hezbollah militia allies, and, crucially, Russian air power. And they’ve been targeting not just insurgents, but civilian areas, schools, hospitals, and aid facilities.

The civilians are trapped. Many are refugees two or three times over, having fled fighting elsewhere in Syria, or been forced out of areas Mr. Assad’s regime reclaimed. Huddling in tents or other makeshift dwellings, with winter temperatures plunging below freezing after sunset, they’re being pushed toward a border that neighboring Turkey has sealed shut.

But the civilians are trapped in another way as well, which adds to the importance of our understanding how the conflict got to this stage, where it may be headed, and what lessons the international community might learn from the victims it has claimed and the depth of suffering it has caused. For even if civilians in Idlib survive the latest fighting, they know their longer-term fate hinges on an intensifying geopolitical tug of war over Syria’s future.

The protagonists

The main protagonists are Russia’s President Vladimir Putin and Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Their uneasy partnership of recent years – in pursuit of a mutually acceptable arrangement over a postwar Syria – is now under huge strain in Idlib.

Turkey, which wants to retain a security zone across the border in northern Syria, has sent in an extra 7,000 troops to support Islamist rebel forces against the Russian-Syrian offensive. Last week, Turkish soldiers came under an artillery and air attack that left at least several dozen of them dead – the largest single loss for Turkish forces in the war.

While they’ve been careful not to blame Russia directly for the attacks – ahead of a planned Putin-Erdoğan meeting in Moscow later this week – the Turks have announced a new offensive against Mr. Assad’s forces. The apparent aim: a cease-fire, negotiated through Moscow, that would include a lasting sphere of influence for Turkey in northern Syria.

But as if that’s not complicated enough, Turkey is also a key NATO state. Mr. Erdoğan is pressing both NATO and the European Union to back him in Syria. So far, there’s little sign of NATO support. He has seriously alienated the alliance by trying to play it off against the Russians, especially by his purchase of an advanced Russian anti-aircraft system over strong U.S. objections.

For the EU, Mr. Erdoğan’s bid for support is especially fraught. Turkey is hosting more than 3.5 million Syrian refugees, under a deal involving billions of dollars of EU funding for the effort. Yet since the attack on Turkish troops in Idlib, Erdoğan has begun sending thousands of people toward neighboring European countries – in effect threatening a repeat of the major 2015 refugee surge that led to a political crisis inside the EU.

The missing players

And that brings us to what Sherlock Holmes memorably called “the dog that didn’t bark.” Largely missing from the diplomatic debate over Syria are the two most historically influential players in the Western alliance: the United States and Britain. They essentially dealt themselves out in 2013, when the British Parliament and, days later, then-President Barack Obama retreated from even limited military action to enforce their “red line” against Mr. Assad’s use of chemical weapons.

Whether the reprisal strike would have provided a meaningful military deterrent is uncertain. But the political and diplomatic message was clear: Especially with the example of the American-led invasion of Iraq, on inaccurate allegations that Saddam Hussein possessed undisclosed stocks of unconventional weapons, there was little appetite for any significant Western military involvement.

That had two important ripple effects. The first was to clear the way for Russia’s military involvement, which ended up rescuing Mr. Assad’s beleaguered regime and turning the war in his favor.

The second was to weaken the prospect of credible Western opposition not just to chemical weapons, but to a wholesale violation by Russian and Syrian forces of decades-old rules governing the protection of noncombatants in conflict zones. The use of barrel bombs against residential areas. The shelling or bombing of schools and hospitals. The deliberate targeting of aid workers.

A key question now is whether the intensified fighting and mounting humanitarian crisis in Idlib will prompt the U.S. and European states to reengage in efforts to end the fighting and influence the future shape of Syria.

Where Turkey is concerned, the EU would seem to have little leverage, given its overriding concern to prevent a repeat of the 2015 refugee crisis. The U.S., however, does have some potential sway as the senior partner in NATO, especially since Mr. Erdoğan has been trying to persuade Washington to give him Patriot anti-missile defense weapons.

Russia, by contrast, does have potential interest in improving its ties with the EU, badly frayed since its seizure and annexation of Crimea from Ukraine. Yet Mr. Putin seems intent on crowning his military involvement in Syria with a decisive victory for the Assad regime, with the added geopolitical bonus of excluding the long-dominant outside power in the Mideast, the U.S., from any meaningful say.

US Marines lead charge in rooting out racism in military ranks

Do Confederate symbols have a place in today’s U.S. military? That question echoes a debate about heritage and hostility in broader society. But for America’s top Marine, the answer is simple.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The United States Marine Corps is often considered a magnet for “tough guys.” But is it also a haven for white supremacists?

Legislators and top-ranking military officials have been grappling with that question in recent years, as polls and congressional testimony have highlighted a persistent thread of racist ideology among the rank and file. Recent interest in the issue among members of Congress has been heartening for many advocates. But congressional action takes time. Last week, Gen. David Berger, the nation’s top Marine, took a decisive step in banning Confederate paraphernalia on Marine bases.

“It’s very encouraging,” says the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Lecia Brooks, who testified at a House Armed Services Committee hearing in December. “It really does seem like the military leadership was listening,” she says.

The move is just one step in one branch of the military services, but General Berger’s announcement “sends a strong signal” to all of the services, says Richard Kohn, former chief historian for the Air Force. What’s more, he adds, the move marks a notable step forward in the U.S. military’s “uneven trend towards trying to live our values” as Americans within the armed services.

US Marines lead charge in rooting out racism in military ranks

Last week, the United States Marine Corps took a step toward rooting out racism in military ranks.

With the decision to ban troops from having Confederate paraphernalia on bases, Gen. David Berger, the nation’s top Marine, weighed in decisively on the side of those who argue that today, these items are more likely to be emblems of hostility than heritage. The move comes amid a broader reckoning, as the U.S. military grapples with the persistence of racism and extremist ideology among rank-and-file service members. Recent interest in the issue among House Armed Services Committee members has been heartening for many advocates, but congressional action takes time – and extensive debate, says Lecia Brooks, the chief workplace transformation officer at the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). General Berger’s decision represents a concrete step forward.

While there is a “real possibility of [troops] pushing back and saying, ‘I should be able to wear my Confederate flag belt buckle,’ if they go up against this, they’re going to lose,” she says. “That’s the beautiful thing about the military. If the highest military leader says that it’s going to be done, then it’s going to be done,” she adds. “I feel really good about that.”

The move, announced last week, comes on the heels of a congressional hearing in which senior Pentagon officials acknowledged a rise in reports of white supremacists within the military ranks. Nearly 1 in 4 service members noted signs of “racist ideology” in the workplace, according to a 2018 Military Times poll. More than half of nonwhite respondents said they had seen and heard everything from the casual use of racial slurs, to the display of Confederate battle flags despite complaints from fellow troops, to tattoos known to be connected with hate groups.

Last year, the Federal Bureau of Investigation also cited an increase in domestic terrorism investigations involving soldiers as suspects. Yet the “majority of soldiers identified as participating in extremist activities are not subjects of criminal investigations,” Joe Etheridge Jr., chief of criminal intelligence at the Army’s Criminal Investigation Command, told lawmakers at the February hearing, echoing the approach outlined by his counterparts in each of the services.

Instead, the military’s response typically involves “advising soldiers that participation in extremist activity will be taken into consideration when writing evaluation reports” and “may impact decisions on leadership assignments,” Mr. Etheridge said. At the same time, leaders counsel soldiers “when indicators of extremist activities are identified, in order to prevent violations of Army policy and/or criminal acts.”

These actions have been deemed wanting, at best, by hate group analysts, who had been heartened by a U.S. House of Representatives addition to the 2020 defense budget requiring the Pentagon to ask whether troops have seen “extremist activity” on base in the hopes that it “may lead to better information on the extent of these problems in the military,” said Heidi Beirich, co-founder of the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism, who testified at the House Armed Services Committee hearing.

Yet a Senate amendment stripped specific references to examining “white nationalism” and “white supremacy” in the military surveys, drawing bipartisan criticism. “If it’s white supremacy, we can’t use the word ‘extremism,’” Rep. Trent Kelly, a Mississippi Republican, told Pentagon officials, arguing that white supremacists should be called just that.

For this reason, the Marine Corps’ move is “huge,” says the SPLC’s Ms. Brooks, who also testified at the February congressional hearing. “It’s very encouraging, because it really does seem like the military leadership was listening” to the points raised in the recent testimony. At the same time, she adds, “The fact that this came from the Marines – it challenges a stereotype I may have had about who’s in the Marine Corps.”

The Marines are considered a magnet for the “tough guys who want to prove their manhood,” says Richard Kohn, former chief historian for the Air Force and now professor emeritus of history, peace, and war at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The service has typically had among the lowest rates of women and racial minorities in its ranks and drew particular attention when Marine Lance Cpl. Vasillios Pistolis was found to have been a member of the neo-Nazi Atomwaffen Division and expelled from the military in 2018. The international group, whose name means atomic weapons in German, has been involved in U.S. murders as well as the creation of, among other crimes, a hit list against liberal German politicians. Mr. Pistolis’ membership in the group was discovered after he violently assaulted counter-demonstrators at the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.

White supremacists have caused alarm in each of services. This winter Coast Guard Lt. Christopher Hasson was sentenced to 13 years in prison on weapons charges in connection with alleged plans to commit domestic terrorism. He was found to have performed internet searches – on his work computer – that included such Googled gems as “homemade C4,” “biological weapon,” and “bomb [Timothy] McVeigh used,” referring to the former soldier who was executed for the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing that killed 168 people.

It is clear that white supremacists place “a premium on the type of training afforded by the U.S. armed forces,” Ms. Brooks says. It’s “no surprise,” she adds, that hate groups “encourage their followers to join a branch of the military, and that they target existing service members for recruitment.” In her view, this makes it all the more vital that the Defense Department is on board with efforts to root out racist criminals within its ranks.

To this end, in addition to General Berger’s zero-tolerance policy, the Pentagon is also working to use new “testing and screening techniques that assess a range of critical personality dimensions to identify applicants who best fit with the military’s culture of treating all personnel with dignity and respect,” said Garry Reid, director for defense intelligence in the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security. These include “commitment to serve, order, selflessness, and tolerance.”

Congress is also pushing the services to create a database of tattoos fashionable among white supremacists, as well as to better monitor the social media of recruits, and eject members who belong to racist groups. Representative Kelly reminded Pentagon officials that they have the ability “without congressional authority to say, ‘If you’re found as an active, passive – any – member in these [hate] organizations, you shall be removed from service.’” Indeed, current distinctions between “active participation” and “membership” in hate groups are confusing and “woefully inadequate for what we know today is a very serious domestic terrorism problem,” said Rep. Jackie Speier, who chaired the House hearing. “We’ll be working with you.”

For now, General Berger’s move marks a notable step forward in the U.S. military’s “uneven trend towards trying to live our values” as Americans within the armed services, Dr. Kohn says. “It took a long time for racial integration to take hold in the military, but if you take a long historical view you see the progression.” Whether the suppression of white supremacism among some service members has “regressed a bit because of the current [U.S.] president, I don’t know – I suspect it has in some circles.”

Perhaps as a result, “The armed services in general and the Marines in particular are very keen to develop and demonstrate a certain kind of culture that unites its troops to perform in combat and buttresses bravery in battle,” he adds. Racism runs counter to this, and General Berger’s announcement “sends a strong signal” to all of the services. “The commandant doesn’t come up on the net with things he considers insignificant.”

Points of Progress

From Sudan to low-Earth orbit, accountability finds footholds

This is more than feel-good news – it's where the world is making concrete progress. A roundup of positive stories to inspire you.

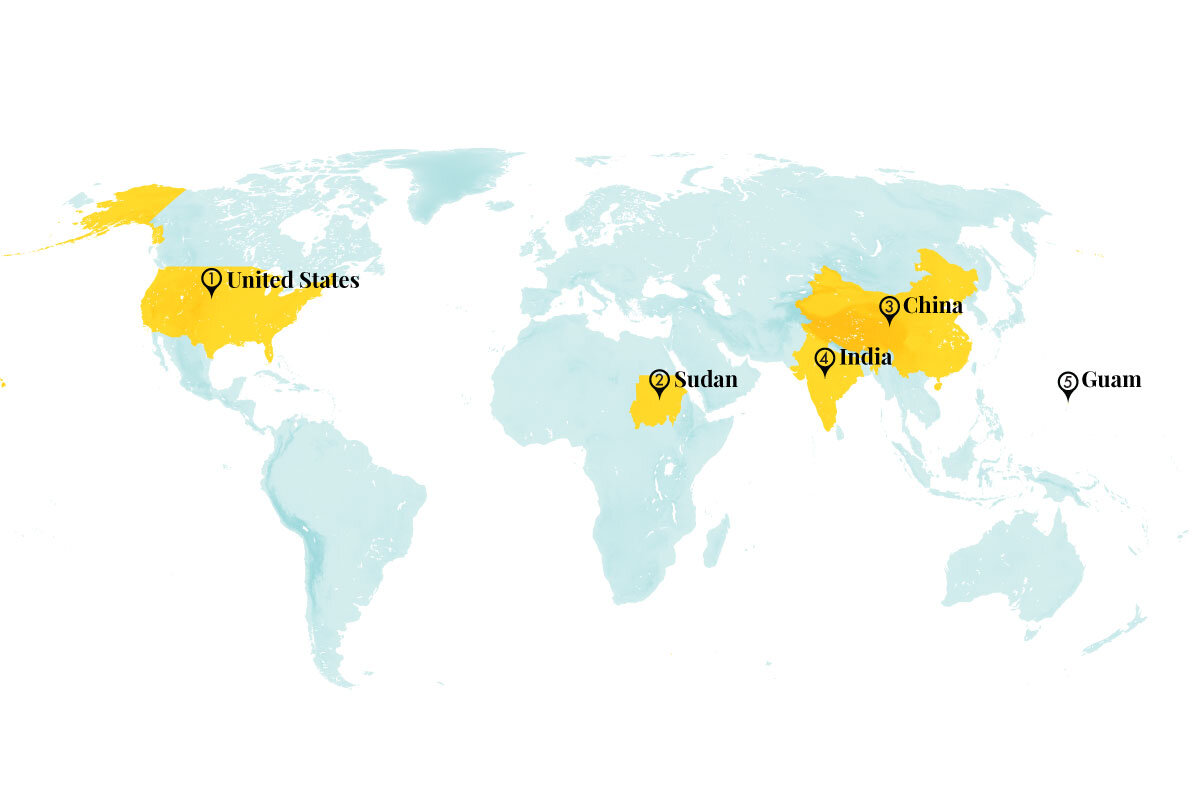

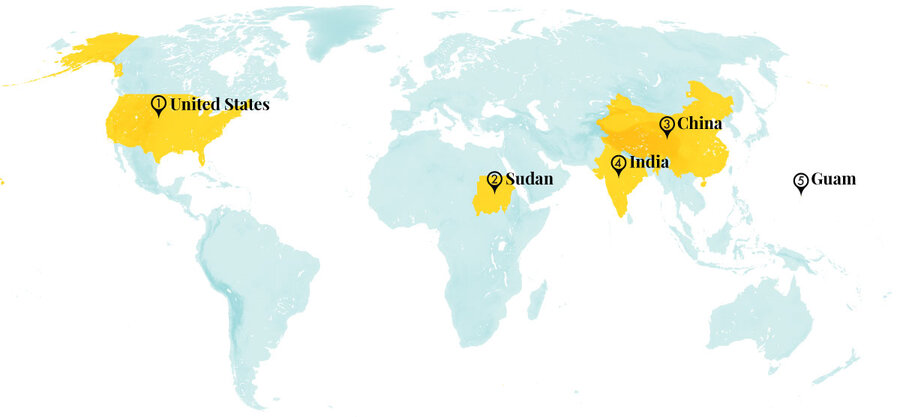

From Sudan to low-Earth orbit, accountability finds footholds

1. United States

The law journals at America’s top 16 law schools are, for the first time, all led by women. The increase in female editors-in-chief – all elected through peer vote – comes during what Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg says is the best time for women in the legal profession. Even so, women account for less than a quarter of law firm equity partners and tenured law professors. Women of color experience even greater gaps in representation. (ZME Science)

2. Sudan

Former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir will face trial in the International Criminal Court for alleged war crimes and genocide. Mr. Bashir’s announced extradition is a product of ongoing peace negotiations between the country’s government and rebel groups in the Darfur region – where more than 300,000 have died during armed conflict since 2003. The ICC first issued an arrest warrant for Mr. Bashir in 2009, and he was ousted from office last April. While the government still has the potential to renege on its commitment to hand over the ex-president, government spokesman Mohammed Hassan al-Taishi says that Sudan is carrying out the will of the people. (BBC)

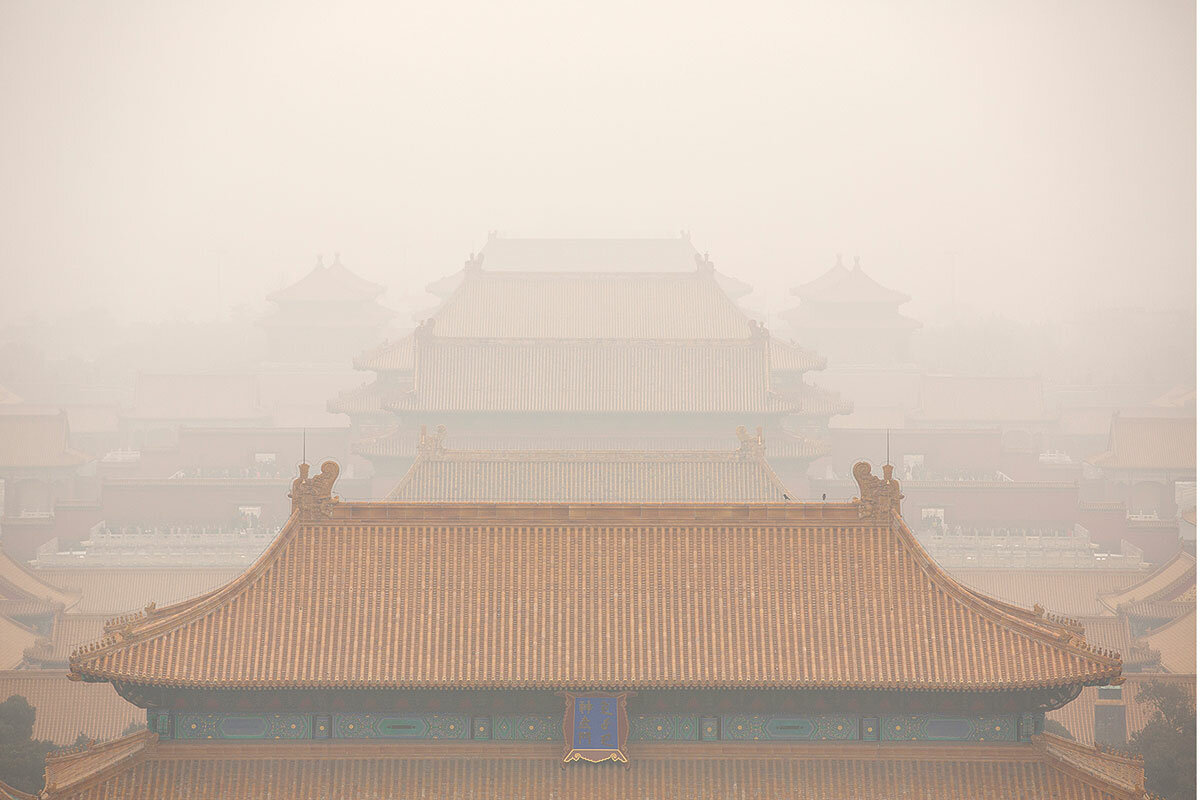

3. China

Beijing committed to reducing the city’s air pollution this year by further regulating greenhouse gas emissions and by increasing the number of electric and hybrid vehicles on the road, lowering Beijing’s reliance on diesel trucks. By continuing an anti-smog campaign begun in 2016, Beijing aims to improve on data released last year that showed improved air quality. The city’s PM2.5 level, a measure of tiny airborne particles, still remains four times higher than the level the World Health Organization considers safe. (Reuters)

4. India

India’s Supreme Court ruled that female army officers are now eligible for permanent commissions, widely seen as an important step toward equality in the country’s armed forces. With women allowed to serve in command roles, men and women will be equal in terms of promotions, ranks, benefits, and pensions. The current system permits women to serve only through the Short Service Commission, a five-year contract with an option to renew but without equal benefits. “The Indian Constitution is based on equality. Denying opportunities to women was against the ethos of the constitution. Now the army will have to frame guidelines that are equal for men and women,” says Lt. Col. Poonam Sangwan. (BBC)

5. Guam

Guam has begun its first publicly funded immersion program to preserve CHamoru, a language indigenous to the Mariana Islands. The pilot program is part of a broader effort to preserve CHamoru as the number of native speakers declines, largely due to decades of Spanish colonial and then U.S. military rule. Last year, the National Science Foundation issued a $275,000 grant to document the language; Chief Hurao Academy, a nonprofit on the island, offers different CHamoru immersion programs. Even as the effort to secure funding remains difficult, some hope that the language will revive as Guam experiences renewed interest in its culture and indigenous language. (The Guardian)

Outer space

The European Space Agency selected Swiss startup Clearspace for the first mission to remove man-made debris orbiting Earth. The project kicks off in March with the goal of launching into orbit in 2025. Meanwhile, the ESA is attempting to establish a new market for cleaning up and servicing objects in outer space, as more satellites launch in increasingly large clusters. Around 2,000 live and 3,000 defunct satellites currently orbit the planet, according to ESA estimates. (Bloomberg)

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Turkey’s threat of a refugee exodus

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Last week, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan threatened to allow up to 1 million refugees now in his country to cross into Europe. To the credit of norms against the use of innocent migrants as weapons, the flow has been much slower than expected.

Instead of a million Syrians and others crossing into Greece, only about 24,000 made the attempt by Monday. Mr. Erdoğan may have decided that generating a migration crisis in Europe was not worth the reputational cost.

His motives for the threat were not entirely clear, but his current circumstances are. He is in a dangerous standoff with Russia over military influence in Syria and wants Western powers to back him up. To get that help, he may have decided to use what is known as “coercive engineered migration,” or driving people toward countries that want regulated flows of migration.

Mr. Erdoğan’s threat was short-lived in part because of a tongue-lashing from German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who often acts as the world’s conscience. She said Turkey was putting the lives of civilians at risk. Even in war, the combatants must make peace with the norms of protecting innocent people.

Turkey’s threat of a refugee exodus

Since last Friday, journalists have camped out on the border between Turkey and Greece watching for fresh flows of migrants. They anticipated something rarely seen in history: one nation exploiting refugees as pawns in a geopolitical struggle.

Last week, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan threatened to allow up to 1 million refugees now in his country to cross into Europe. To the credit of global norms against the use of innocent migrants as weapons, the flow has been much slower than expected.

Instead of a million Syrians and others crossing into Greece, only about 24,000 made the attempt by Monday, according to Greek officials. Mr. Erdoğan may have decided that generating a migration crisis in Europe was not worth the reputational cost. The world’s moral standards against exploiting vulnerable refugees appear to be holding.

Mr. Erdoğan’s motives for the threat were not entirely clear, but his current circumstances are. He is in a dangerous standoff with Russia over military influence in Syria and wants Western powers to back him up. To get that help, he may have decided to use what is known as “coercive engineered migration,” or driving people toward countries that want regulated flows of migration. This nonmilitary tool is sometimes used by weak countries against stronger ones. Libya under Muammar Qaddafi tried it with Europe while Cuba under Fidel Castro employed it several times against the United States. Recall the Mariel boatlift of 1980 off Florida.

Mr. Erdoğan’s threat was short-lived in part because of a tongue-lashing from German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who often acts as the world’s conscience. She said Turkey was putting the lives of civilians at risk. In his policy dispute with the European Union, Mr. Erdoğan was “taking it out on the backs of refugees,” she said. “That’s the wrong way.”

To its credit, Turkey has hosted 3.7 million refugees from Syria’s civil war since 2011. It deserves Western aid for this generous hospitality. And the EU as well as the U.S. needs to absorb more of the refugees. But Mr. Erdoğan cannot expect the West to let him exploit refugees for his national goals in Syria. Even in war, the combatants must make peace with the norms of protecting innocent people.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Contributing to a better mental atmosphere

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

What might happen if we more often considered what kind of atmosphere we’re contributing to at home, at work, out running errands, or even at the polls? Wherever we find ourselves, each of us has a God-given ability to express kindness, compassion, and patience.

Contributing to a better mental atmosphere

We have a favorite Chinese restaurant we go to where not only is the food excellent, but the atmosphere of consistent kindness, friendliness, and readiness to serve keeps us going back.

Atmosphere is an everyday fundamental. For example, while waiting in a long line, we can be patient or impatient. I have to admit it has gone both ways, in my case! But I have seen how expressing patience can help take an edge off a generally impatient atmosphere.

With polarization, division, and misunderstandings filling the airwaves, the global emotional thermostat appears to be turned up. I can’t help wondering what might happen if we more often asked ourselves, and answered honestly, what kind of atmosphere we are contributing to at home, at work, or out running errands – and whether we are helping to make it a better one.

Something that has helped me to more effectively do this in my own life is to consider things from a spiritual basis. For instance, this verse in the Amplified Bible indicates that our real atmosphere is God-given and spiritual: “For in Him we live and move and exist [that is, in Him we actually have our being],... For we also are His children’” (Acts 17:28).

This throws light on atmosphere as steady and stable – sustained by God, divine Spirit. And what makes up the atmosphere of Spirit? The infinite spiritual qualities that make up the nature of God as Love and Mind. Peace, joy, and purity permeate this atmosphere.

The understanding that it’s natural for us to express such qualities as God’s spiritual creation can help uplift our surroundings. It empowers us to express characteristics such as kindness, compassion, and patience. We realize that because these qualities are derived from God, fear and anger have no true authority or legitimacy to dominate and pervade the atmosphere of our daily lives.

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science – which is solidly rooted in the Bible – highlighted God’s nature when she wrote: “Spirit is symbolized by strength, presence, and power, and also by holy thoughts, winged with Love. These angels of His presence, which have the holiest charge, abound in the spiritual atmosphere of Mind, and consequently reproduce their own characteristics” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 512).

Christian Science explains that angels are not beings with wings, but pure thoughts from God, dwelling within the atmosphere of the divine Mind. We can pray for all our thoughts to be inspired by this Mind. Such good, beneficent, powerful thoughts are always coming to us from God, bringing protection, purity, and healing, wherever we find ourselves.

Here’s a small but meaningful example. My husband and I were driving on a rainy day, when suddenly we felt the impact of another car hitting the back of ours.

Before getting out of the car to talk with the other party involved, we prayed to express calm toward them.

When we approached the other driver, she started yelling and blaming us for what had happened. But instead of being drawn into an argument, we simply expressed regret for what had happened. It wasn’t that we were capitulating or refusing to stand up for ourselves. Rather, we felt so clearly that our thoughts were “winged with Love,” that we knew the pure atmosphere of Spirit was enveloping all of us, this other woman included.

The effect was immediate. The driver stopped yelling. The whole tone of a condemning, angry atmosphere completely dissolved. When the police arrived, we all had a harmonious discussion about next steps. We were soon on our way, feeling completely at peace.

Science and Health states: “An odor becomes beneficent and agreeable only in proportion to its escape into the surrounding atmosphere. So it is with our knowledge of Truth” (p. 128). Each of us can take this to heart, sincerely striving to think and act from the standpoint of the spiritual reality: that the atmosphere of Spirit, Love, is everywhere and always blesses. In this way, we can’t help but contribute to a better atmosphere in the world around us.

A message of love

After the storm

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about whether Brazil’s cattle ranchers can save the Amazon with more eco-friendly beef.

Before you go, we’d like to offer a quick clarification. The lead story in Monday’s edition included a graphic depicting a decline in coal consumption in China that lacked context. The sustained decline was due to the coronavirus outbreak.