- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- COVID, race, and a pivotal moment for America

- Nuclear arms control: What happens when US and Russia let it lapse?

- Ohio governor’s science-based COVID response wins bipartisan praise

- Digging up forgotten kingdoms, Saudis unearth ancient identity

- Jules Feiffer, a stubborn pooch, and a children’s counting book

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Amid protests, the power of being heard

It’s another moment where the significance of powerful words and meaningful action is on full display.

Earlier this year, they eased fear and isolation as the pandemic crescendoed. Now, as Americans absorb the killing of George Floyd, an African American, as he was detained by Minneapolis police officers, they are again offering a salve. Peaceful protests have been punctuated by nights of looting and violence, as well as police brutality. But alongside those images is another narrative: of people hearing each other.

In Minneapolis, volunteers rallied Thursday to clean up from a night of looting. “This is love in action,” said resident Ming-Jinn Tong. GoFundMe efforts are helping damaged businesses. After violence broke out amid peaceful protests in Seattle Saturday, hundreds of volunteers flocked Sunday to scrub graffiti and board up broken windows. “It’s … showing each other who we really are,” said Nicolai Quezada. In Louisville, white women linked arms and stood between black protesters and police, while elsewhere in the city, Chris Williams, a black protester, linked arms with others to protect a lone officer.

Across the country, police raised their voices. In Santa Cruz, California, the chief of police took a knee alongside peaceful protesters. In Camden, New Jersey, officers joined a march against racism. Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo, connected with the Floyd family via a CNN interview, removed his hat as he spoke of the officers present as Mr. Floyd died. “Being silent, or not intervening, to me, you’re complicit,” he said. “If there were one solitary voice that had intervened, that’s what I would have hoped for.” And in Michigan, Genesee County Sheriff Chris Swanson met protesters with officers in riot gear and carrying batons. Protesters sat; the police removed their gear. “You tell us what you need,” Mr. Swanson said. “Walk with us! Walk with us!” came the chant. And they did.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

COVID, race, and a pivotal moment for America

Certain years loom large as icons of challenging times for America. 2020 is likely to join the roster amid a pandemic, massive protests over racially charged police killings, and deep economic stress.

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

Stressed by the calamity of the coronavirus, clashing over reopening the economy, divided by partisanship and race, America itself seems afire, as big cities reel from days of unrest sparked by the death of George Floyd in police custody last week in Minneapolis.

Videos of the violence are disturbing. National leadership appears absent. Plans for the pandemic vary by state, while the nation struggles with unprecedented unemployment. Is pressure from multiple crises causing U.S. democracy to unravel?

Probably not, say historians. In wars and depression, America has survived intact through worse. But 2020 seems likely to become an inflection-point year studied by future students, like 1918 (deadly flu pandemic), 1929 (stock market crash), and 1968 (urban riots).

And while the nation has had pandemics, war, political violence, political polarization, rebellions, and economic depression before, only in 2020 has it had them all combined, notes Robert Vinson, a professor of history at The College of William & Mary.

As a historian, Dr. Vinson says he feels the nation fraying apart, the social contract being damaged. The next six months or so could be crucial to the country’s future.

“This is really a fork-in-the-road moment,” he says.

COVID, race, and a pivotal moment for America

St. John’s Episcopal Church, across Lafayette Square from the White House, is a butter-yellow Washington icon. Many presidents have worshipped there, among them Abraham Lincoln, who would slip into the back corner of the last pew, seeking respite from the weight of his office, always sitting alone.

On Sunday night, as unrest ripped through cities across the nation, St. John’s was set ablaze.

Escorted by police, D.C. firefighters put out the blaze and initial inspections showed no significant damage. But the metaphor remains apt. Stressed by the calamity of the coronavirus, clashing over reopening the economy, divided by partisanship and racism, America itself seems afire, as big cities reel from days of unrest sparked by the death of George Floyd last week in Minneapolis.

Videos of the violence are disturbing. National leadership appears absent. Plans for the pandemic vary by state while the nation struggles with unprecedented unemployment. Is pressure from multiple crises causing U.S. democracy to fray, even unravel?

Not literally, say some historians. In wars and depression, America has survived intact through worse. But 2020 seems likely to become an inflection-point year studied by future students, like 1918 (flu pandemic), 1929 (stock market crash), and 1968 (urban riots).

The atmosphere and events of 1968 may be the most comparable to today. Vietnam was a catastrophe building in the background. Then came sudden shocks, including the shootings of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. Cities exploded.

“In terms of my own experience, it feels more like 1968 in the aftermath of the MLK assassination, because of all these uprisings happening simultaneously,” says Eric Foner, professor emeritus of history at Columbia University and author of “The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution.”

As in 1968, black Americans today are more likely to be economically disadvantaged than white people. As in 1968, many today feel the sting of racial prejudice, as evidenced by a spate of police killings of black men.

In some ways, the circumstances of 2020 are not so much a repeat of 1968’s as an extension of them, says Robert Vinson, a professor of history at The College of William & Mary.

“Structurally and systemically, there are very clear connections and similarities and continuities,” he says.

The role of leadership

Many of the protests sparked by the death of George Floyd in police custody have been peaceful processions with a multiracial mix. But many have descended into scenes of violence and looting resulting in curfews in various cities and the deployment of thousands of National Guard members in at least 15 states.

President Donald Trump and Attorney General William Barr have, without evidence, accused far-left anarchist actors known as “antifa” of orchestrating many of the protests. On Monday, in a conference call, President Trump called governors “weak” in the face of continuing violence, and urged them to “dominate” unruly protesters. If they don’t, they’re “wasting their time,” said the president.

Yet aside from tweets, President Trump himself has been mostly silent on the protests, with the exception of brief remarks on Saturday when he was in Florida to watch the launch of U.S. astronauts.

“I stand before you as a friend and ally to every American seeking justice and peace,” said the president. “Healing, not hatred, justice, not chaos, are the mission at hand.”

In some cities, police officers have been reprimanded for the kind of harsh tactics that produced the protests in the first place. In Fort Lauderdale, an officer was suspended for shoving a kneeling woman to the ground during a protest. Two Atlanta officers were fired after bashing in the window of a car and using a stun gun on occupants, according to The Associated Press.

Other police officers have tried to calm the situation by kneeling in solidarity with protesters or accompanying them on a march.

In Savannah, Georgia, for instance, a crowd of protesters surrounded a small group of officers at the city’s historic police station. The officers were clad in riot gear and tensions seemed to rise, according to Monitor correspondent Patrik Jonsson.

Then Savannah Det. Joshua Flynn began to shake hands with and hug protesters who approached him. The officers stood their ground as protesters inched closer, some yelling sharp words. But as the standoff continued, the protesters took up a different chant: “Walk with us! Walk with us!”

In this case, the police demurred. But later, officials allowed the protesters to clamber atop a National Guard truck and use its sound system to disperse the march at its end.

A history of protests

In 1968, some 110 U.S. cities suffered civil disturbances following the killing of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, with the largest riots in Baltimore, Washington, Kansas City, and Chicago. They followed the spate of unrest of the long hot summer of 1967, including an explosive uprising and riot in Detroit that left 43 dead and was controlled only with the help of elements of the regular Army’s 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions.

There was another wave of violent protests in 1992, following the acquittal of police officers who had used apparently excessive force, caught on video, while arresting Rodney King.

In recent years, the Black Lives Matter movement has held protests against police brutality in many American cities. In 2015, the death of Freddie Gray in police custody in Baltimore led to violent protests following Mr. Gray’s funeral.

In that context, the current wave of protests is not at all unprecedented, says Pamela Oliver, a professor emerita of sociology at the University of Wisconsin who studies racial disparities in criminal justice.

“It’s very American. We do it a lot,” she says. “We have a lot of issues with racial violence and policing.”

This does not mean that America has made no progress on race, says Dr. Foner of Columbia University. There’s been a black president. African Americans hold political power in many cities. Police departments have made efforts to diversify and retrain their officers.

But the pace of that progress has been slow, and left some important problems untouched.

“The virus and George Floyd’s death have illustrated that not enough has changed,” says Dr. Foner.

In 1968, the underlying condition shaping the national mood was Vietnam. It was the deadliest and most expensive year of the war for the U.S. and its allies, and much of that fighting, and dying, fell to minorities.

In 2020, the underlying condition is the coronavirus, which has disproportionately affected African Americans and other minorities. With unemployment reaching record levels, the economic fallout is hitting minority communities harder too.

“There is a deep, deep sense of frustration and injustice, and it only takes an incident for that to come rolling out,” says Joe Dunn, chair of history and politics at Converse College and an expert on the protest movements of the 1960s.

A fork-in-the-road moment

America has weathered pandemics, war, political violence, political polarization, rebellions, and economic depression before 2020.

But only in 2020 has the nation faced all of them combined, says Dr. Vinson of William & Mary.

As a historian, Dr. Vinson says he feels the nation fraying apart, the social contract being damaged. The next six months or so could be crucial to the country’s future.

“This is really a fork-in-the-road moment,” he says.

The twin public health emergencies the U.S. is facing are COVID-19 and the long-standing “virus” of systemic racism, says the William & Mary professor. Fighting them will require a fundamental reconceptualization of what community means, in his view.

Looking at groups as “us” versus “them” in a time of intertwined political and health issues doesn’t work, he says.

“It’s not those folks over there in that urban center who are separate somehow from the rest of us. It’s all of us being impacted by this. And all of us have a responsibility to see it as such, because otherwise we may all go down,” says Dr. Vinson.

Staff writer Patrik Jonsson contributed to this report from Savannah, Georgia.

Nuclear arms control: What happens when US and Russia let it lapse?

Could we be moving away from aspirations of a world free from nuclear weapons toward a world free from nuclear arms control? This story shows what that might look like.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In May, President Donald Trump announced the United States will be leaving the Open Skies Treaty, which supports arms control by allowing countries to overfly each other’s territory on demand. Next, New START, which made sweeping reductions to strategic nuclear arsenals, will expire in February, with the Trump White House showing little desire to extend it.

That leaves the world’s biggest nuclear powers set to plunge back into the strategic chaos that prevailed in the early 1960s, before the Cuban missile crisis.

The Trump administration says that alleged Russian violations have made the old agreements unworkable. And many Russian experts admit that Russia has been less than fully transparent. But there is strong evidence that the Russians never wanted to wreck the process.

“One of the goals of Russian foreign policy is to restart talks about these treaties, not to let them die,” says Alexander Golts, an independent Russian analyst. “[Mr. Trump] and his people see no need to tie the U.S. down to any obligations at all. He is absolutely sure of U.S. superiority in any situation. It’s a false perception, but that seems to be where we are today.”

Editor's note: The original version misstated the historical scope of New START's reductions to nuclear arsenals.

Nuclear arms control: What happens when US and Russia let it lapse?

The world is sleepwalking toward a period free of nuclear arms control, as New START, the last remaining nuclear weapons treaty, is set to expire next February.

This dark horizon has been approaching for quite a while, but the political will to avert it has collapsed. The Trump White House has spent its term withdrawing from arms control treaties – the latest being the Open Skies Treaty last month – and shows little interest in extending New START. And Russia has not been able to woo the U.S. back to the negotiating table, despite a desire to keep the process going.

Now the biggest nuclear powers appear ready to plunge back into the strategic chaos that prevailed in the early 1960s, before the Cuban missile crisis focused the minds of terrified U.S. and Soviet leaders and led them to initiate a multigenerational effort to construct what became a comprehensive system of nuclear arms control.

In the early 1960s “we walked up to the edge of the nuclear abyss with the Cuban missile crisis. Then we walked back and started negotiating,” says Alexandra Bell, senior policy director for the Washington-based Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. “In retrospect, we were lucky to make it out of there alive the first time. Arms control gave us guard rails against chaos. It will be really bad if, for the first time in 50 years, we don’t have any on-the-ground insight into each other’s military forces.”

Arms control waning

The wake of the Cuban missile crisis brought not only restraints on the once-burgeoning numbers and types of new weapons, but also reduced tensions with trust-building measures, channels of regular communication, and reliable verification mechanisms. That structure survived the end of the Cold War, as did the massive, global-life-threatening nuclear forces of the U.S. and Russia.

Several U.S. presidents added their own contributions to the network of accords. As recently as a decade ago Barack Obama inked New START, the deal that made sweeping reductions to strategic nuclear arsenals, with his Russian counterpart Dmitry Medvedev.

But the edifice erected by Cold War-era leaders has been gradually unraveling since George W. Bush unilaterally pulled the U.S. out of the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, which had served as a keystone for the whole system by placing tough caps on defensive systems. That had ensured absolute mutual deterrence in the form of mutual assured destruction (MAD), thus making the very idea of nuclear war unthinkable.

Things have been shaky ever since, though arms control experts on both sides have insisted until recently that the system might be revived if leaders wanted it. But the Trump administration, which seems averse to any limitations on U.S. power, has buried the whole idea by tearing up quite a few international treaties. Specifically, it recently pulled out of the 1987 Intermediate Nuclear Forces treaty, which had banned an entire class of nuclear missiles and was dubbed “the treaty that ended the Cold War.”

In May, Mr. Trump announced the U.S. will be leaving the Open Skies Treaty, a 2002 agreement signed by 34 nations, which supports arms control by allowing countries to overfly each other’s territory on demand. Most U.S. allies have complained that leaving it will be a destabilizing act. Next, Mr. Obama’s New START, which had allowed for 18 on-site inspections per year, will expire in February without earnest efforts – of which there is little sign – on both sides to extend it.

Divided intentions

The Trump administration says that alleged Russian violations have made the old agreements unworkable, and that new players such as China have become full-fledged strategic nuclear powers that would need to be included in any fresh arms control regime.

U.S. arms control experts agree with the White House that Russia has sometimes violated agreements around the edges. And many Russian experts admit that Russia has been less than fully transparent, and has often tried to play technical issues to its advantage. But there is strong evidence that the Russians never wanted to wreck the process. As the U.S. was pulling out of the INF Treaty, for example, the Kremlin rushed to propose new talks, and offered to let U.S. inspectors examine the missile that was the alleged source of the “violation” claim. The Trump administration pulled out anyway.

The Kremlin has always valued the arms control process because it was the only arena where they face the U.S. across the table as equals. Alexander Golts, an independent Russian analyst who is presently at Uppsala University in Sweden, says that the Kremlin uses arms control to stave off global isolation over other issues.

“One of the goals of Russian foreign policy is to restart talks about these treaties, not to let them die,” he says. “At least the Russian approach creates the opportunity to talk. Trump’s way is much more primitive. He and his people see no need to tie the U.S. down to any obligations at all. He is absolutely sure of U.S. superiority in any situation. It’s a false perception, but that seems to be where we are today.”

Mr. Trump’s own chief arms control negotiator, Marshall Billingslea, explicitly expressed that view recently, saying that the U.S. doesn’t want a new arms race with Russia or China, but is fully prepared to defeat them the same way the U.S. won the old Cold War. “We know how to win these races, and we know how to spend the adversary into oblivion,” he said.

No choice but to come back to the table

Andrei Kortunov, head of the Russian International Affairs Council, which is affiliated with the Foreign Ministry, says new forms of arms control will undoubtedly be needed in the future. The most dangerous thing about the present moment is that the old tried-and-true framework is being destroyed before any new controls have been even envisioned. The dangers of miscalculation or misunderstanding will multiply amid that vacuum, he says.

“Over the past 50 years we have developed a common strategic culture with our American counterparts. We were talking the same language, and everyone knew what the terms meant.”

If that common culture, all the mechanisms of dialogue, trust-building, and verification are lost, Russia will probably not try to match the U.S. missile for missile as the USSR did in the past, he adds.

“In the absence of any arms control, it will become almost impossible for the U.S. to know what we really have or what we may be able to do. Russia is likely to follow a policy of ‘strategic ambiguity,’ to keep them guessing as a means of deterrence. That would be a very dangerous state of affairs, one that nobody would wish for,” Mr. Kortunov says.

Ms. Bell says the U.S. and Russia will eventually come back to the table. “Between us, Russia and the U.S. have more than 90% of all existing nuclear weapons, and we are the only two countries capable of posing an existential threat on that scale,” she says. “So, asking if Russia is a good partner is the wrong question. We basically have no choice but to start a sustained new conversation with them.”

Mr. Kortunov agrees. “Eventually we’ll have to devise new forms of arms control to ensure strategic stability. Probably it will be different, encompassing 21st century realities like space, cyber, and artificial intelligence. And it will have to be multilateral. Let’s hope we won’t have to go through some new Cuban missile crisis before we get to that point.”

Editor's note: The original version misstated the historical scope of New START's reductions to nuclear arsenals.

Stepping Up

Ohio governor’s science-based COVID response wins bipartisan praise

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine has his state firmly behind him for his leadership amid the pandemic. In an interview with the Monitor, he shares what matters most as he makes decisions.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Before a single case of COVID-19 had been reported in his state, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine began imposing sweeping restrictions. The mild-mannered Republican banned spectators from large-scale sporting events, and was the first governor in the nation to close public schools.

Now, as Ohio begins to gradually reopen, public health experts say the governor’s swift actions likely helped the state avoid the fate of its northern neighbor, Michigan, or that of many East Coast hot spots.

At a time when responses to the virus seem increasingly marked by partisanship, Governor DeWine’s apolitical, fact-based approach has earned him plaudits from both sides of the aisle. A Washington Post-Ipsos poll found that 86% of Ohio voters approve of the way Mr. DeWine has dealt with the coronavirus – the highest rating of any governor. To many, the Ohio governor’s decidedly non-flashy style of leadership – a competence shaped by decades of experience – seems to be what’s needed at this moment of crisis.

Governor DeWine himself is quick to stress that given the stakes, politics are beside the point.

“We’re dealing with people’s lives,” he says in an interview. “These are the most important decisions I will ever make in my life.”

Ohio governor’s science-based COVID response wins bipartisan praise

Before a single case of COVID-19 had been reported in his state, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine began imposing sweeping restrictions. The mild-mannered Republican banned spectators from large-scale sporting events. He recommended that colleges suspend in-person classes. He was the first governor in the nation to close his state’s public schools, and he fought to postpone Ohio’s primary election.

The moves may have seemed radical at the time, but as Ohio now begins to gradually reopen, having recorded just under 2,000 deaths so far, public health experts say the governor’s swift actions likely helped the state avoid the fate of its northern neighbor, Michigan, or that of many East Coast hot spots.

At a time when responses to the virus seem increasingly marked by partisanship, Governor DeWine’s apolitical, fact-based approach has earned him plaudits from the media and sky-high approval ratings from voters on both sides of the aisle. To many, the Ohio governor’s decidedly non-flashy style of leadership – a steady competence, shaped by decades of experience – is exactly what’s needed at this moment of crisis.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

“The way I’ve approached this is to get all the information, to rely on the best science that’s available,” says Governor DeWine, in an interview with the Monitor that took place in mid-May. “Forty years of doing politics and government, the mistakes I’ve made is because I didn’t get enough facts ... and I didn’t trust my gut instinct. And my gut instinct throughout this has been we needed to move faster.”

The longtime Ohio politician, who has variously served as a United States senator, a congressman, and his state’s attorney general, has often been labeled “nerdy” or “boring” due to his subdued manner and scandal-free career. But that low-key image masks the roll-up-your-sleeves attitude of someone who just comes in and gets the work done, says Joe Hallett, a retired political journalist who wrote for several Ohio newspapers.

“Experience matters,” says Mr. Hallett. “DeWine has been inside government and knows what levers to pull and push. He’s not someone given to stunts.”

Mr. Hallett witnessed that tenacity firsthand in 1994. While covering Mr. DeWine’s campaign for the U.S. Senate, the reporter found the then-lieutenant governor lying in the back seat of a car, trying to pass a kidney stone. He was in pain, but refused to cancel that evening’s event.

“He struggles out of the car and goes in, there’s about 100 to 150 people in there for dinner, and DeWine winces his way through the door and instantly his demeanor changes,” says Mr. Hallett. “He goes from table to table and shakes every single hand, suffering on the inside but nobody was the wiser.”

Nearly 30 years later, Mr. DeWine harnessed this quiet, steely resolve again to slow the spread of COVID-19.

A Washington Post-Ipsos poll released May 12 found that 86% of Ohio voters approve of the way Mr. DeWine has dealt with the coronavirus – the highest rating any governor received in its poll, and solidly bipartisan (Democrats actually rated his job slightly higher than Republicans). By contrast, 45% of voters approved of President Donald Trump’s efforts.

The governor himself is quick to dismiss those numbers, recognizing that they’re likely to come back down as the challenge moves into new phases. And he stresses that given the stakes, politics are beside the point.

“Those poll numbers are nice, but that’s not where they’re going to stay – and that’s OK,” he says. “We’re dealing with people’s lives. These are the most important decisions I will ever make in my life.”

Early on, daily press briefings with the governor and his team of public health experts quickly became prime-time viewing for thousands of Ohioans eager for information about the virus’s spread and the state’s lockdown orders.

“[They] were so good at presenting ideas and giving people the opportunity to digest them and process them before they were implemented,” says Deborah Hellmuth Bosner, who runs an optometry practice in the Columbus area. “It’s about setting expectations. I was always able to start preparing as a [business] what shutdown procedures would look like, where we might need to go.”

In the beginning of the crisis, before much data had been collected, Mr. DeWine would often emphasize the lack of information and uncertainty to the public. For Greg Laux, a trial lawyer in Cincinnati, it was refreshing to hear a politician be so candid, or admit to not knowing something. He says the briefings also demonstrated the trust Mr. DeWine places in Ohio Department of Health Director Dr. Amy Acton and other scientific experts.

“In a crisis, I think people look for confidence, someone who is knowledgeable, an expert, and competent,” says Mr. Laux, who started a Facebook fan group for Mr. DeWine. “Mike DeWine is one of the best political leaders of my lifetime.”

Still, not all Ohioans have agreed with the governor’s decisions. Protesters marched in front of the Statehouse throughout April and May, imploring the governor to reopen the state. He partially relented on April 28, reversing an order that required retail customers to wear masks.

But the Republican governor has remained adamant that wearing a mask is a matter of public health and is “not about politics” – a stark contrast with fellow Republican President Trump, who has conspicuously avoided wearing a mask in public.

To some, it’s striking that the Ohio governor – an establishment Republican for his entire political career – would take such a markedly different approach from his party’s current leader. But during his 12 years in the U.S. Senate, Mr. DeWine was generally regarded as a moderate Republican, one who was at times willing to buck the party line and work with Democrats.

Mike Curtin, a former reporter and editor at The Columbus Dispatch who covered the governor extensively over the course of his career, adds that at this stage in his career, the governor is a “free man.”

“The difference between Governor DeWine and Mike DeWine in his previous political iterations is that he understood that this was his final stop,” he says. “If this were a Mike DeWine 25 years younger than he is, he probably would not be quite as independent as he’s been.”

Mr. Curtin – who had a partial stake in a minor league baseball team owned by Governor DeWine’s son until he sold it in 2019 – says that freedom has helped the governor remain data-driven throughout this crisis, heeding his public health experts’ advice.

“It allows him to follow the science, to be true to his heart,” he says. “People tend to appreciate that, and that’s why he’s getting the virtual standing O’s – he’s being his authentic self.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Digging up forgotten kingdoms, Saudis unearth ancient identity

As Saudis excavate temples and statues long lost to shifting sands, they are embracing a rich heritage. But they could do it only after an official shift in attitude toward pre-Islamic history.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Mesopotamia, Egypt, Phoenicia, Persia. The civilizations have echoed through the centuries. Yet while most of the Middle East was rich in legendary city-states, the vast Arabian deserts were, for generations of archeologists, flyover country. A blank spot on the map of the ancient world.

But in northwest Saudi Arabia, Dadan and Lihyan, two Arab kingdoms from the first millennium B.C. that once ruled vital trade routes, are being unearthed. Their remnants are woven into the landscape: Temple columns, 1-meter-thick brick walls, rock-carved tombs, detailed statues, and inscription-scrawled boulders poke out among date farms and houses.

Saudi citizens are pointing to the kingdoms as proof that they are the latest in a proud lineage stretching back millennia – that there is more to being a Saudi than oil and religion.

“We saw photos of a rock tomb in a history book, but we thought these were a cursed people that had nothing to do with us,” says Mohammed Abdullah, a university student from Jeddah, as he walks by hundreds of carved inscriptions and drawings. “We never thought that these people were Arabs and could be our ancestors.”

“This is something to really be proud of.”

Digging up forgotten kingdoms, Saudis unearth ancient identity

Tarek never knew his daily commute was in the footsteps of ancient Arab kings.

The 30-year-old Al Ula resident runs his hands over the exposed brick and rock inscriptions he has known since a child as “the ruins,” listening as a tour guide lists the achievements of the tribes that built a kingdom on these sands 3,000 years ago.

Squinting at the rock-carved tombs in front of him, he sees something greater than a civilization: a connection.

“They prayed, they grew dates, they performed pilgrimages and welcomed visitors to the oasis like we do today,” Tarek says as he stops to pose for a selfie in front of a rock engraving.

“They lived just like us.”

Today Saudi authorities and archaeologists are unearthing and promoting Dadan and Lihyan, two Arab kingdoms whose traces have lain under sand and obscurity for centuries. Cited in the Old Testament and ancient Greek texts, the ancient kingdoms once ruled vital trade routes.

Saudi citizens are pointing to the kingdoms as proof not only that this arid region was home to civilizations centuries before the modern oil boom, but that the people of Saudi Arabia are the latest in a proud lineage stretching back millennia – that there is more to being a Saudi than oil and religion.

“Missing piece” of ancient map

Mesopotamia, Pharaonic Egypt, Phoenicia, Persia. These names of Middle Eastern civilizations have echoed through the centuries, capturing humanity’s imagination, recalling greatness, and inspiring art, literature, films, and entire fields of study.

Yet while most of the Middle East and Mediterranean were rich in legendary city-states, the vast Arabian deserts were, for generations of archeologists and academics, flyover country of little note or historical value. A blank spot on the map of the ancient world.

If they were so great, where are the monuments? Where are the cities?

The cities, it turns out, are still being unearthed. And what has already been uncovered of Dadan and Lihyan in the deserts of northwest Saudi Arabia has turned conventional wisdom on its head.

Here in Al Ula, the remnants of these sprawling desert kingdoms from the first millennium B.C. are woven into the landscape: Temple columns, 1-meter-thick brick walls, rock-carved tombs, detailed statues, and inscription-scrawled boulders poke out among date farms, houses, and newly-established eco-resorts.

Most of what scholars know today of these kingdoms is from the hundreds of rock inscriptions scrawled across the area in the Dadanite language, a Semitic offshoot, telling of kings and pilgrims, migrant communities, and daily life and death. And taxes.

On a Saturday in March, Thuraya, an Al Ula resident, guides visitors through Jabal Al Ikma, one of Al Ula’s craggy gorges scrawled with hundreds of pristine Dadanite, Lihyanite, and early Arabic inscriptions.

“This is their library, a collection of their civilization and stories carefully carved into stone,” says Thuraya, who was trained to interpret rock art.

“Lihyanites and the Dadanites,” she says “were advanced kingdoms that you could put in the same sentence as ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia.”

The Dadanites controlled the lucrative trade of incense – namely frankincense – which was cultivated in Yemen and carried on camel caravans through Dadan en route to temples in Pharaonic Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Levant, where this fragrant tree resin played an important role in religious ceremonies.

Centuries before the Nabataeans rose up from Petra, in modern Jordan, as the dominant ancient Arab power, the Dadanites used the incense trade to transform this sleepy palm-dotted oasis into a regional economic powerhouse.

“Incense was the petrol of the times, this is why Dadan flourished,” says Abdulrahman Alsuhaibani, an associate professor at King Saud University in Riyadh who has been leading excavations at Dadan for the past decade.

What has been excavated speaks to their advancements: one temple features perfectly square tombs and intricate lion statues carved into the rockface. At another, wells and an 8-foot-tall stone basin believed to have been used for ablution by pilgrims coming to give tribute to a pantheon of gods suggest an advanced water management system.

In the fifth century B.C., another tribe built upon Dadan to create Lihyan, an empire extending west into the Gulf of Aqaba and Sinai and north toward the Levant.

What has been uncovered speaks to the Lihyanites’ influence: two imposing larger-than-life statues of Lihyan kings, standing like half-robed pharaohs, were recovered at a Lihyanite temple and have since been on tour in Paris.

More than 3,000 smaller statues were found inside the Temple of the Lions in six weeks of excavations alone. Local residents say they have seen “dozens” of statues and human-shaped stone idols over the years while picnicking in the valleys.

This is likely because Lihyan’s economic juggernaut was built not only on incense trade, but on tribute paid at its temples. It also was a hub for dried dates, which have grown in abundance here for nearly 3,000 years and travel well on weekslong desert treks.

Today, this same oasis accounts for one-third of Saudi Arabia’s date production and is renowned across the country. Stop by any shop or home, and an Al Ula resident will eagerly offer you a platter of the sugary-sweet halweh and burni dates that once powered this ancient kingdom.

Such was Lihyan’s fame, ancient Greek cartographers and Pliny the Elder referred to the Gulf of Aqaba as the Gulf of Lihyan, a name that was in use for three centuries.

But then, shortly before the first century B.C., the rival Nabataeans from southern Jordan inhabited Lihyan and transformed it into the town of Al Hajr, or Hegra, the second city of their empire. Within years, all mention of Lihyan suddenly stopped.

A few miles to the north, the Nabataeans built Madain Saleh, majestic tombs carved into rock mounds that rival Petra.

With such rich and diverse history, archaeologists are now calling Al Ula an “undiscovered country.”

But that’s only because for so long this site was overlooked by Orientalists chasing Biblical and Hellenistic lore and shunned by Saudi governments who saw the remains as the un-Islamic relics of pagans.

Only since 2017 has the Saudi leadership devoted a vast amount of resources for the archaeological investigation and preservation of Al Ula, in the process informing its citizens of these lost civilizations.

Newfound pride in history

Mohammed Abdullah, a 22-year-old university student from Jeddah, hoists up his phone as he walks between the hundreds of inscriptions and drawings carved into the gorge of Jabal Ikma, livestreaming his visit.

“We saw photos of a rock tomb in a history book, but we thought these were a cursed people that had nothing to do with us,” says Mr. Abdullah. “We never thought that these people were Arabs and could be our ancestors.”

“This is something to really be proud of.”

The Royal Commission for Al Ula, along with French, German, and British teams and colleagues from King Saud University, will expand excavations and are set to undertake specialized studies to learn more how these ancient peoples lived, cultivated, and traded here over the millennia.

Already excavations have unearthed almost as many questions as statues.

Are the Dadanites and Lihyanites the same people? What happened to the Lihyanites? Why are they not mentioned once in the hundreds of Nabataean inscriptions in Al Ula or elsewhere?

But for many, the most important question has been answered: What’s so special about ancient Saudi Arabia?

“We have civilizations on the Arabian Peninsula that are no less than the ancient civilizations in Mesopotamia, the Levant, and Egypt,” says Mr. Alsuhaibani, the archaeologist.

“We should be proud of our history, and we are on our way to let people know about it.”

Books

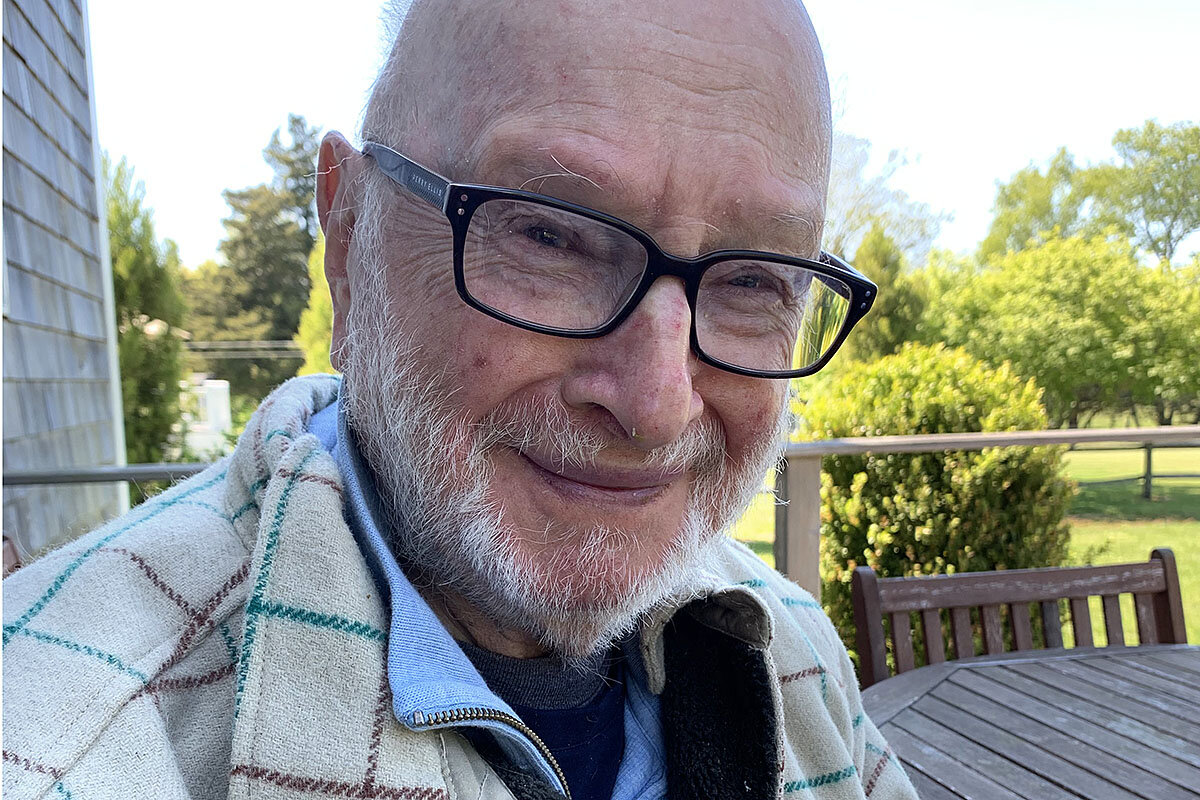

Jules Feiffer, a stubborn pooch, and a children’s counting book

When cartoonist Jules Feiffer pivoted to children’s literature late in his career, many of his fans might have been surprised. But the shift, he says, connected him to one of his own childhood joys.

-

By Peter Tonguette Correspondent

Jules Feiffer, a stubborn pooch, and a children’s counting book

As a boy coming of age in the 1930s and ’40s, Jules Feiffer had his head buried in the funny pages.

“My earliest ambition, my earliest dreams, and my earliest joy was in looking at, particularly, the Sunday supplements – the color supplements,” says Mr. Feiffer, who in time became a Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist. “It was pure and beautiful and innocent in a time when innocence was allowed.”

Forging his own path in the field of cartooning, however, Mr. Feiffer often gravitated toward dark, biting satire. He maintained a weekly comic strip in The Village Voice from 1956 to 1997. The comic strips were collected into books, and the title of one such volume demonstrated his acidic take on politics and society: “Sick, Sick, Sick.”

Comics historian Brian Walker situates Mr. Feiffer within a tradition of 1950s-era antiestablishmentarians, including comedian Lenny Bruce and the Beat writers. “They used to call it ‘sick humor’ – that term was used almost in a derogatory way about this new, topical, confessional humor,” Mr. Walker says.

In 1993, however, Mr. Feiffer decided to try a genre that would ultimately reconnect him with his beloved Sunday supplements: children’s literature. HarperCollins has just published “Smart George,” a sequel to one of Mr. Feiffer’s most enduringly popular books, “Bark, George,” from 1999. The original book, which focused on a canine named George who barks only after much prodding, has sold more than 300,000 copies.

The long-deferred sequel centers on the same stubborn pooch: This time, George, struggling with his addition, dreams that he is schooled in math by a cat, a gaggle of farm animals, and a mustachioed veterinarian who will be familiar from the earlier book. The concept sounds straightforward enough, but Mr. Feiffer had long struggled with a sequel.

Several years ago, as he was about to embark on a long car ride from his home outside New York City, he resolved to produce an outline before the trip was over. “I fiddled and faddled and wrote notes in my head and jotted things down,” he says. “And, my God, by the time I got to the city, I had the sequel.”

To longtime readers of his Village Voice strip, Mr. Feiffer’s late-career turn toward children’s literature might have come as a surprise. In the quarter-century since his debut in this genre, a young adult novel, “The Man in the Ceiling,” Mr. Feiffer has churned out a steady stream of works for younger readers. “Combining visual and verbal storytelling from his very first Village Voice strip, doing picture books just seems like a natural outcome,” says Michael di Capua, Mr. Feiffer’s editor.

At first, Mr. Feiffer resisted drawing animals. “But, somewhere along the line, it became fun,” he says.

He says that he instructs young cartoonists to follow their instincts. “I’m not so much the author of these things,” he says. “I’m experiencing the book as it happens, and I just happen to be the guy pushing the pencil or pen or brush around,” he says.

Mr. Feiffer – currently working on another sequel, “Park George” – has no plans to put away his drawing tools anytime soon. “I’m 91 now,” he says. “When I sit down at my drawing table, I can do anything that I’ve ever done, it turns out.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

What U.S. protesters can learn from Ferguson

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The protests in U.S. cities demanding justice for George Floyd, a black man who died under the knee of a white police officer, have not spared Ferguson, Missouri. This city in St. Louis County first sparked a movement nearly six years ago after a similar police killing, turning it into a global symbol of racial inequities. On May 30, Ferguson again saw demonstrations. Only this time they were different in one key aspect. The city’s police chief, Jason Armstrong, greeted the protesters and condemned the killing in Minneapolis.

His gesture, while small, is an example of the lessons that Ferguson can offer to the rest of the United States. The city’s limited reforms since the 2014 killing of Michael Brown show that progress in even discussing inequalities may help prevent police brutality toward minorities. They also build on the continuum of good that has unfolded in America’s consistent, if imperfect, pursuit of a more compassionate and just society.

What U.S. protesters can learn from Ferguson

The protests in U.S. cities demanding justice for George Floyd, a black man who died under the knee of a white police officer, have not spared Ferguson, Missouri. This city in St. Louis County first sparked a movement nearly six years ago after a similar police killing, turning it into a global symbol of racial inequities. On May 30, Ferguson again saw demonstrations. Only this time they were different in one key aspect. The city’s police chief, Jason Armstrong, greeted the protesters and condemned the killing in Minneapolis.

His gesture, while small, is an example of the lessons that Ferguson can offer to the rest of the United States. The city’s limited reforms since the 2014 killing of Michael Brown show that progress in even discussing inequalities may help prevent police brutality toward minorities. They also build on the continuum of good that has unfolded in America’s consistent, if imperfect, pursuit of a more compassionate and just society.

In a report last year on police reform in the St. Louis area, the watchdog group Forward Through Ferguson found that a mix of vision, persistence, and pressure has brought a measure of change to the region. Tangible progress included the election of a black prosecuting attorney in St. Louis County and the creation of a civilian review board for the regional police department. These days, a political candidate doesn’t run for office without addressing racial inequities – even though the region remains one of the most racially segregated metro areas in the U.S. In numerical terms, the St. Louis region has seen progress in 46 out of 100 “equity indicators” set down by the Ferguson Commission, a panel set up after the 2014 killing.

“There is a huge opportunity for St. Louis to be a national model for how to confront these issues and come out stronger for it,” David Dwight of Forward Through Ferguson told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch last year.

Yet for all the attention on “systemic” reform, perhaps the most important insight is that acts of change require acts of new relationships. “We need to take care of each other to do this work,” stated the 2019 report on police reform. “Finding common ground and understanding perspectives thought to be oppositional are often instrumental to building the trust needed to try new things.”

In unexpected ways, the response to the Michael Brown killing brought people together in St. Louis. “People in communities all across the region not only wanted to talk about these issues,” concluded the Ferguson Commission in 2015, “they also wanted to do something about these issues.” People listened with patience and respect that carried with it a sense of purpose, obligation, and resolve.

In other words, they acted much like Ferguson’s police chief last Saturday in greeting the protesters. The divisive perception that people are naturally unequal begins to quickly fall away with simple acts of love and empathy. They are the highest form of protest.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Love

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Mary Baker Eddy

Many are yearning for greater peace, justice, and harmony in the world. “Thou to whose power our hope we give,/ Free us from human strife,” prays the author of this poem, which points to the power of God, divine Love, to unify and heal. (Read the poem or listen to the poem being sung.)

Love

Brood o’er us with Thy shelt’ring wing,

’Neath which our spirits blend

Like brother birds, that soar and sing,

And on the same branch bend.

The arrow that doth wound the dove

Darts not from those who watch and love.If thou the bending reed wouldst break

By thought or word unkind,

Pray that his spirit you partake,

Who loved and healed mankind:

Seek holy thoughts and heavenly strain,

That make men one in love remain.Learn, too, that wisdom’s rod is given

For faith to kiss, and know;

That greetings glorious from high heaven,

Whence joys supernal flow,

Come from that Love, divinely near,

Which chastens pride and earth-born fear,Through God, who gave that word of might

Which swelled creation’s lay:

“Let there be light, and there was light.”

What chased the clouds away?

’Twas Love whose finger traced aloud

A bow of promise on the cloud.Thou to whose power our hope we give,

Free us from human strife.

Fed by Thy love divine we live,

For Love alone is Life;

And life most sweet, as heart to heart

Speaks kindly when we meet and part.

Audio attribution:

Words: “Love,” by Mary Baker Eddy (courtesy of The Mary Baker Eddy Collection)

Music: Désirée Goyette

Performed by Rebecca Minor

Music © 2016 The Christian Science Board of Directors

A message of love

In solidarity

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Please join us again tomorrow. Included in our stories will be Patrik Jonsson’s look at the impact of using violence in protest.