- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Why talk of looting moved a shopkeeper to give

If you’re a home cook then you’ve probably heard of Penzeys Spices.

Bill Penzey launched the company in the late 1980s in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, as a mail-order operation. Mr. Penzey, an activist capitalist, peppered his early catalogs with his politics and never stopped letting people know where he stood.

As befits a culinary alchemist, he’s for science. He’s against the use of Native American iconography in sports.

Now he’s stirring himself into the debate over what constitutes a collateral cost of righteous protest and what’s just wanton destruction. After the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Mr. Penzey again grew vocal about racial injustice and the need to fight it.

Penzeys has a store in Kenosha. Someone wrote Mr. Penzey to ask if he’d feel differently if his store were being damaged in the unrest.

His Minneapolis store had its windows broken after George Floyd’s killing in May. Penzeys responded with a sweep-up and a “hope mural” on the plywood that replaced them. But Mr. Penzey didn’t cite that bit of history. He thought the question through, he told customers in a letter.

“What if we looted our own store?” he said he asked his team. Snapshot its inventory; earmark it for dispersal to food pantries and “organizations trying to raise money to fund change.” He’s now asking his customers where the products should go.

“Human life means everything,” Mr. Penzey wrote, “stuff, not so much.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Global report

Young workers hit hardest in global downturn. What’s the answer?

The world’s newest workers face a slipperier on-ramp than even those who launched into the Great Recession. We look at some of the responses that might boost their prospects, and their confidence.

-

Whitney Eulich Special correspondent

-

Lenora Chu Special correspondent

-

Ann Scott Tyson Staff writer

-

Jules Struck Staff writer

Gina LoPresti, a recent college graduate in Holland, Pennsylvania, lost her restaurant job in March. Her plans to transition to a job in teaching or nonprofit work have been put on a long and indefinite hold.

Around the world, unemployment has surged due to the coronavirus pandemic, hitting workers age 15 to 24 especially hard. Colombia and Sweden have youth jobless rates of about 30%. And historically, the effects on young people’s income can last long after a recession ends.

Nations are seeking answers. China is easing exam rules so more people can work as rural doctors. Germany is leaning on its strong school-to-work pipelines to keep youth joblessness low at 5.6%. In the U.S., some groups like the YMCA of Greater Boston are trying to boost the quality of the youth jobs they offer, if they can’t boost the quantity.

The positive experiences are important, as some research has made a link between heightened youth unemployment and diminishing self-confidence and negative social behaviors.

“You kind of just want to give up,” says Ms. LoPresti. “But getting out of that funk is really important, because while it’s horrible right now, the pandemic isn’t going to be forever.”

Young workers hit hardest in global downturn. What’s the answer?

It seemed, at first, like a joke.

“It was like, ‘Ha ha, we all lost our jobs because of COVID; we’ll be back in two weeks,’” recalls Gina LoPresti, who lost her restaurant job in March.

Then reality sank in for the recent college graduate. She wasn’t asked to return to the restaurant. She moved back in with her parents in Holland, Pennsylvania. While she still has savings from her job and no student debt, her plans to work and save up before transitioning to the job she really wants – as a teaching assistant or at a nonprofit – have been put on a long and indefinite hold.

“The past month, I haven’t even applied to jobs,” she says, “mostly because a lot of places due to COVID either aren’t hiring at the moment or they’re looking for people that have ... experience that I know I don’t have.”

Juliana Quiñones, a Colombian millennial, left her job in social work on Colombia’s northern coast in December, hoping to find something new in the field of environmental development in Bogotá. Then, in late March, after a surge of coronavirus cases, the entire country shut down. Businesses closed. And youth employment soared to nearly 30%, one of the highest rates among nations that the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) ranks as industrialized. Young women were especially hard hit: More than 1 in 3 are now jobless.

“Let’s just say it was bad timing,” Ms. Quiñones says of her job search. Today she’s trying to launch an eco-fashion shoe line from her parent’s home.

Around the world, from Colombia to Sweden, China to the United States, high-income nations have seen unemployment rise as they’ve locked down their economies. Joblessness has hit workers age 15 to 24 especially hard. Depending on the country, youth unemployment is running double or even triple the jobless rate for the general population. And the effects may last long after the coronavirus is brought under control. If the pandemic-led recession mimics previous downturns, young workers now looking for their first job could see depressed earnings for as long as a decade and more frequent joblessness over a lifetime. And there are concerns about the mental impact joblessness can have on young people.

“Each country will be in a slightly different context [but] it seems to be a global situation,” says Ronald McQuaid, professor of work and employment at the University of Stirling in Britain.

Time for tax incentives for hiring the young?

Will this generation of young workers be any different than the millennials a decade ago, when they started their job search in the teeth of the Great Recession and endured reduced earnings and more unemployment, as a result?

Part of the answer lies with the pandemic itself. If a resurgence causes new lockdowns in nations, the economic damage could last beyond those entering the workforce in 2020 or 2021, says Jesse Rothstein, professor of public policy and economics at the University of California at Berkeley. His research shows that in the U.S., those who start looking for work during a downturn earn 2% less for up to a decade and experience longer bouts of joblessness than those who join the workforce during normal times. Some studies put the damage to incomes higher still.

Even if the past turns out to be prologue, “there will always be exceptions,” says Professor McQuaid. The trend “is a propensity, not a predestination.”

In fact, part of the answer also lies with what governments and private agencies decide to do to alleviate the situation. Most immediately, that involves fiscal stimulus to offset the effects of the downturn, economists say. Longer-term solutions involve everything from job training to tax cuts and even military recruitment. Some job-training directors are also aiming to boost the quality of jobs that organizations are offering youth.

Sweden addressed its high youth unemployment in 2007 with a payroll tax cut for companies that hired workers 26 years old or younger. For the eight years that it ran, the program not only boosted youth employment, its effect doubled near the end of the program and continued even after the tax cut was eliminated, according to one 2019 study.

“Large payroll tax cuts aimed at youth could be a useful policy as we come out of this [COVID-19] crisis that has hit the young particularly hard,” writes Emmanuel Saez, director of the Center for Equitable Growth at the University of California at Berkeley, in an email. “It is possible that a large shock like COVID reverses the gains, and that a new special policy toward the young will be needed to speed the recovery.”

At nearly 29%, Sweden has the fourth-highest youth unemployment rate in the industrialized world, behind Spain, Greece, and Colombia.

Crisis and response in Colombia

The Colombian government is taking several steps to address the problem. That includes programs to pay school fees for low-income students in an effort to keep them enrolled in the education system, federal contributions to help companies keep formal workers on the payroll, and doubling down on existing efforts, like making it easier for citizens to apply for entrepreneurial licenses.

Civil society has stepped up, as well. Futbol Con Corazon (Soccer with Heart), a nongovernmental organization based in Barranquilla, works through soccer to empower disadvantaged youths, age 5 to 17, in communities across the country. One of the central parts of the program is to help them create life plans, envisioning options like higher education or professional careers. This year, the group is launching a new initiative in partnership with Atlético Nacional, one of Colombia’s biggest professional soccer clubs, that will train former participants to become program coaches and mentors.

Masses of unemployed young people cost a nation far beyond jobless subsidies and lost payroll taxes.

“When a young person can’t be in the education system and can’t find employment, they become easy recruits for illegal activities and groups, or they become victims or victimizers,” says Juan Sebastián Arango, a presidential adviser on Colombian youth, ticking off illegal industries that have long plagued the nation like trafficking and illegal mining. “We have to put youth at the center of these policies.”

One feature of youth unemployment is that it swells every summer as high school and college students graduate. Nowhere is that stress larger than in China, where a record 8.7 million young people completed college and university this year. That’s the equivalent of adding the population of Switzerland to China’s workforce every year.

And this year, it will be especially tough to find jobs for them as the economy slows. Recruiters were seeking 2.5 million fewer graduates in the first quarter of this year, compared with last year. The unemployment rate for young workers peaked at 13.8% in April, with a slight drop in July. That’s double the overall national unemployment rate, which is based on the urban workforce and does not reflect joblessness among China’s rural population, including roughly 300 million migrant workers.

In China, new jobs as soldiers or rural doctors

Government and private-sector initiatives – together with stepped-up army recruitment – are underway to open up opportunities for graduates. For example, China’s state Cabinet in June approved a pilot in 16 provincial areas that will allow Chinese college students majoring in clinical medicine to apply to work as rural doctors without a time-consuming exam process. Easing the requirement will also alleviate a shortage of rural physicians. A similar program will open doors for graduating veterinarians.

“We must remove such unreasonable barriers to job entry and ... help with the employment of college graduates,” said Chinese Premier Li Keqiang at a June 24 Cabinet meeting, according to the official China Daily newspaper.

Some of China’s large tech and communications companies are launching recruiting drives. The Chinese internet giant Tencent is seeking to hire 5,000 graduates this year, the most in the company’s history, and a 40% increase over last year.

In Hong Kong, the number of job openings for the territory’s 30,000 new university graduates plummeted more than 40% in the first four months of 2020, compared with the same period last year. Luke Chu, an experienced digital marketing specialist, just completed a master’s degree in Hong Kong. But after sending out dozens of resumes, he is still waiting for an interview. “I’ll try to lower my salary expectations,” Mr. Chu was quoted as saying in China Daily.

“Only supermarkets were hiring”

After two pandemic-related layoffs in Germany, Lena at least still has a job, although for reduced hours and at lower pay. The young bilingual émigré from China, who didn’t want her last name used for privacy reasons, had worked in fashion retail for 40 hours a week in Düsseldorf. Then the pandemic hit. “For two months everybody was closed,” she recalls. “Only supermarkets were hiring.”

Now she works part time at an H&M store, earning a third of what she used to. Her income, now diminished to 600 euros a month, pays food and rent while she finishes a degree in fashion marketing. She’s already worried about finding solid work after graduation.

“The fashion industry is lacking a pulse right now,” she says.

Vocational gateways that work in Germany

To combat youth unemployment, Germany decided to focus on propping up the country’s vocational education and training system. Available to all who complete compulsory schooling, this system is historically the most important gateway into the labor market, used by two-thirds of Germans, says Werner Eichhorst, head of research at the IZA Institute of Labor Economics, a nonprofit research group in Bonn. The current generation of teens can use the help.

“They are disproportionately affected, they suffer lasting negative effects,” says Dr. Eichhorst. The program matches young people into temporary jobs at participating companies, overlaid with vocational training, in an arrangement that typically leads to permanent employment after three years.

During the pandemic, realizing that vocational apprenticeships might take a back seat in company priorities, Germany’s federal government has worked to offer one-time bonuses to firms that stepped up training or took over apprenticeships from other, more strapped companies. “And it looks like the market is functioning quite nicely,” says Dr. Eichhorst. “Most [new graduates] should find an opportunity,” he says. “I’m quite optimistic that in Germany, at least, young people will not suffer a lot.”

Germany’s youth unemployment is holding steady at about 5.6%, the lowest among all industrialized countries except Japan, according to OECD data.

Big gap to fill in the U.S.

The situation in the United States looks more dire, despite some improvement since the spring. Youth unemployment peaked at 26.9% in April and by July had dropped to 18.5%.

That’s still the highest youth unemployment for a July since the economy was emerging from the Great Recession a decade earlier. And it has received little attention from the federal government.

“It’s a really serious issue. But there has not been any policy – period – to assist new job entrants,” says Susan Houseman, vice president and director of research at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, a nonprofit research organization in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Private groups are doing what they can, but the economic squeeze has slashed the number of jobs they can offer. Newly minted college graduate Matthew McLeod-Warrick planned to teach English abroad, but as the pandemic made its way around the globe, the programs offering him a position began canceling.

“I was really disappointed,” says Mr. McLeod-Warrick, who moved back in with his dad in Lynn, Massachusetts. “There are certain jobs that are hiring that I know I could get into, so I know I might not be unemployed for that long. [But] I want to be doing something ... that’s going to help me in terms of my long-term goals. And that might not happen.”

Last summer, the YMCA of Greater Boston employed 725 teens; this summer, it’s closer to 425. But there’s a silver lining, says President and CEO James Morton. “There’s more emphasis today to making sure that young people get meaningful experience and not just busywork.”

The YMCA, which has dramatically ramped up its nutrition programs this year because of the downturn, has put its teen employees in charge of packing and distributing the food. “Young people are bagging groceries that they know will feed a family in the community,” Mr. Morton says.

The positive experiences are important, as some research has made a link between heightened youth unemployment and diminishing self-confidence and negative social behaviors.

“You kind of just want to give up,” says Ms. LoPresti, the unemployed restaurant worker in Pennsylvania. “But getting out of that funk is really important, because while it’s horrible right now, the pandemic isn’t going to be forever.”

Reporting for this article was done by Laurent Belsie and Jules Struck in the Boston metro area, Ann Scott Tyson in Seattle, Whitney Eulich in Mexico City, and Lenora Chu in Berlin.

Editor’s note: As a public service, we have removed our paywall for all pandemic-related stories.

Why the future of elder care may be fewer nursing homes

Now to the other end of the generational spectrum. Even during a pandemic, it turns out, families don’t need to trade away a sense of belonging for their elders in order to give them safety and security.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

The pandemic has shined a spotlight on the often-obscured lives of Americans in nursing homes, and the industry that runs them. But even before COVID-19, alternatives to institutional care were expanding in many states – and now, advocates see a chance to help more Americans age the way they want to.

Smaller-scale, better-staffed elder care appears to have done better during the pandemic. The greater prize, though, is letting seniors age in their homes and communities, providing a sense of belonging. Models vary, from publicly-funded day centers to small modular houses that can be added to existing properties or built in clusters. Today, more than half of Medicaid dollars are spent on home- and community-based services.

Some advocates say the root of the industry’s problems is not money or policy but social attitudes. In an age-stratified society, caring for the old isn’t a common goal but a headache to solve, so vulnerable elders are sent to homes staffed by low-paid carers.

Geriatrician Bill Thomas, who founded the Green House movement to reimagine nursing homes, hopes to see a generational shift. What COVID-19 has done, he says, is change the velocity: “Instead of hoping to make something happen in 10 years we’re trying to make it happen in 10 months.”

Why the future of elder care may be fewer nursing homes

When geriatrician Bill Thomas first sat down to reimagine American nursing homes, the risk of a deadly pandemic wasn’t on his mind. His vision was of elder-directed care on a human scale, an alternative to the “big box” homes staffed and run like hospitals.

Nearly two decades on, the Green House movement he birthed has spread to 300 homes in 32 states. And when COVID-19 hit, its design features – clusters of small buildings with private rooms and bathrooms – helped to reduce infections, even in hard-hit cities like Boston and Detroit.

Dr. Thomas says these features provide a sense of belonging which most nursing homes lack. And they lead to better health outcomes. “If you fix the broken heart it’s also good for the body, and it’s good for preventing infections,” he says.

For decades, reformers like Dr. Thomas have attempted to improve nursing homes. They have built alternative models – less institutional, smaller scale, better staffed – that appear to have done better during the pandemic.

But the greater prize is to help more elders age in their homes and communities. As COVID-19 roils the nursing home industry and the federal spending behind it, that goal may be in reach, reformers say.

“Most people would prefer to age in place, at home, if at all possible. The COVID epidemic might strengthen that, as people feel safer at home,” says Anne Montgomery, co-director of elder care improvement at Altarum Institute, a nonprofit health consultancy.

The vast majority of Americans aged 65 and older currently live at home. But seniors who require support services often end up in nursing homes because they rely on Medicaid to pay for long-term care. In recent years, alternatives to institutional care have expanded in many states, using Medicaid waivers. More than half of Medicaid dollars are spent on home- and community-based services today.

Now COVID-19 has shined a spotlight on the often-obscured lives of around 1.5 million Americans, with more than a third of deaths coming in nursing homes. The pandemic has upended the finances and reputations of home operators. It has disrupted the profitable flow of new residents discharged from hospitals. And it has forced the industry more generally to defend its poor record on infection control and other measures of quality and safety.

“The compact that people have made is to trade away certain freedoms and autonomy, and even respect and dignity, in return for a promise of security and safety. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed that they [nursing homes] have not been able to fulfill that,” says Kavan Peterson, a Seattle-based advocate and co-founder with Dr. Thomas of ChangingAging.

Nursing homes have pushed back against critics, pointing to the rapid spread of COVID-19 in urban areas where hard-hit homes were located. They also say public-health officials failed to provide needed equipment and guidance.

Regardless, the challenges they face are significant.

“Nursing homes have been set up to fail. They have extremely vulnerable populations,” says Michael Barnett, assistant professor of health policy and management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “They have workers who are underpaid and are largely immigrants and minorities who live in communities that are the worst affected.”

New vision

Alternatives to traditional nursing homes vary from $4,000-a-month private assisted-living facilities to publicly-funded adult day centers to at-home visits by carers. PACE Centers, which already provide a wide array of services to the elderly and disabled in 31 states, are another path to expanding non-institutional care options.

A major impediment to independent senior living is cost. “Not everyone is going to be able to afford to pay people for basic assistance to age in place and stay at home,” says Ms. Montgomery of the Altarum Insititute.

One modest solution is a new federal program, Community Care Corps. It recently awarded $2.4 million in grants to 23 nonprofits nationwide. The nonprofits will deploy volunteers to support family caregivers, seniors, and people with disabilities living independently. Altarum Institute is helping to evaluate its effectiveness. “This is the age of volunteerism. We need more volunteers,” says Ms. Montgomery, also a former policy adviser to the Senate Special Committee on Aging.

For his part, Dr. Thomas wants to reimagine what that home looks like. Only 10% of U.S. housing is considered age-friendly.

His vision is a home that is age-friendly, affordable, and woven into a community of all ages so that elders can sustain the connections that he sees as essential to longevity. He’s designed a small modular house he calls a Minka that can be added to existing properties or built in clusters to create new communities. The houses can be as small as 330 square feet, but are designed for the elderly and their needs. Affordable housing can also be set aside for young renters who can help seniors with daily tasks.

In the Netherlands, city planners have added housing for students in buildings and courtyards with seniors, as well as making it easier for families to build add-ons for the elderly.

Dr. Thomas hopes such innovations can spur a generational shift in the U.S. away from nursing homes as inevitable. That shift is already underway, as home and community care grows more popular, and policymakers grapple with the costs of long-term care.

What COVID-19 has done, he says, is to change the velocity: “Instead of hoping to make something happen in 10 years we’re trying to make it happen in 10 months.”

Dene Peterson, age 91, has spent the pandemic in her Appalachian co-housing community in Abingdon, Virginia, which has around 40 seniors. Her ElderSpirit Community formed a task force that set down some ground rules: social distancing, no house visits, masks required outside.

As a result, she says, “We’ve had no contamination here at all.”

While Ms. Peterson misses aqua aerobics class at the local pool, she has learned to socialize with her neighbors via Zoom. The app was introduced by “the young people” – the 60-year-olds.

The former nun founded ElderSpirit in 2006 as a way to age in place together, and her mixed-income, multifaith community for ages 55 and up thrives on mutual support.

“One of the best things is the fact that we manage ourselves,” she says. “We’ve set up so that everybody has a chance to be useful.”

Those with heightened medical needs can choose to move to assisted living, or arrange family caregivers or home health care in the comfort of their residence. Ms. Peterson plans on the latter. “It’s one of the best ways of growing old that I know,” she says. “You’re not lonely.”

Doing the math

Even the most ardent critics of “big box” homes accept the need for nursing homes in an aging society. Over the last decade, the number of 65-and-older Americans has grown by a third to 54 million, according to Census Bureau data. Home-based care is harder to regulate than nursing facilities and providers face similar challenges in recruiting low-paid carers.

In tough economic times, families also find it harder to care for their elders; caregivers already face the burden of lost earnings and reduced pensions. While Medicaid pays for traditional nursing care as a safety net, eligibility for home and community services varies by state.

Nursing home operators have long complained that reimbursements from Medicaid, averaging $200 a day, are too low to pay for the skilled nursing that residents need. Many homes use Medicare payments for post-acute short-term care to cross-subsidize their long-term beds.

This funding structure is one reason why few new nursing homes were being built, even before COVID-19, relative to the growing elderly population.

In 2003, Steve McAlilly built the first Green House nursing home in Tupelo, Mississippi. The organization he leads, Methodist Senior Services, now has 19 homes statewide. All are built to Dr. Thomas’s design of small buildings with individual rooms, staffed by nurse aides who also cook and clean and are known as shahbaz, denoting a higher status than normal aides. (Dr. Thomas is no longer formally involved with the Green House Project, which is based in Linthicum, Maryland.)

Mr. McAlilly’s nonprofit also operates a traditional 60-bed nursing home. When COVID-19 began spreading in local nursing homes last month, he took all precautions to protect his residents. In the 60-bed home, 26 residents tested positive and 3 died, and 20 staff were also sickened, he says. By contrast, only one Green House had a small outbreak and nobody died.

“The same management, the same culture. The only difference is the design,” he says.

Susan Ryan, senior director of the Green House Project, says only six residents in 245 homes surveyed nationwide have died of COVID-19. Facility layout was one factor. Another was staffing: The shahbaz model means residents don’t see a cadre of nurses, aides, and other workers.

“The direct care staff that is providing care to the elders are also doing the cooking and cleaning, and that means there are fewer people coming to do those activities,” she says.

Key moment

Green Houses cost more to build and most are run by nonprofits, while the rest of the nursing-industry mostly follows a model that is more like a hospital than a home.

But a for-profit operator in Arkansas has begun to build more Green Houses, rather than expand other types of care homes, says Mr. McAlilly. The pandemic has made families rethink traditional nursing facilities. The developer “believes this is the future,” he says.

Developers tend to build large nursing homes because scale is seen as necessary in an industry that relies on federal reimbursement that operators say hasn’t kept pace with costs. Those costs have risen during the pandemic, while income from both long-term residents and short-term Medicare-funded stays has declined.

Still, some advocates say the root of the problem exposed by the pandemic is not money or policy but social attitudes. In an age-stratified society, caring for the old isn’t a common goal but a headache to solve, so vulnerable elders are sent to homes staffed by low-paid carers.

In polls, around half of Americans over 40 say that “almost everyone” is likely to need long-term care, but only 25% believe this applies to them. Advocates say this mismatch helps explain why policymakers have been slow to reform the nursing-home sector.

“We have ageism and we have racism and that has had a tremendous impact on what we’re seeing. As a society we have accepted what some call warehousing. We have almost dehumanized elders, they have been the Other,” says Ms. Ryan of the Green House Project.

She adds: “If we don’t take this pandemic and learn from it, shame on us.”

Staff writer Sarah Matusek contributed reporting.

Editor’s note: As a public service, we have removed our paywall for all pandemic-related stories.

How fish farming in Gulf of Mexico could transform seafood trade

Aquaculture is often hailed as a smart, sustainable solution to global food insecurity. But it’s a solution with its own set of hurdles. Which entities – with what values – will make the rules? We found an initiative that aims to balance benefits and environmental cost.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

A proposed deep-water fish farm about 40 miles off Florida’s coast could reshape the world’s seafood industry and upend the lives of the region’s fishermen.

If approved, Velella Epsilon would be the first aquaculture project in federal waters off the contiguous United States. There, globe-shaped pens would cultivate up to 64 million pounds of sushi-quality almaco jack fish meat each year, creating stiff competition for those who ply the Gulf’s wild-catch fisheries, as well as opportunities for fishermen hoping to supply bait for the project.

At stake is whether markets and permits are enough to tackle the larger ethical questions about how to integrate fish farming into the complexities of a system that includes not just the Gulf of Mexico, but Americans who make a living off it.

“How much of the landscape and the seascape should human beings be using?” asks Philip Cafaro, a philosophy professor at Colorado State University. “You have to be explicit about what your goals are. If it’s to maximize profits in the fishing industry, that’s one thing. If your goal is to maximize output to the fishing industry in order to protect communities, that’s a very different one.”

How fish farming in Gulf of Mexico could transform seafood trade

The long, choppy quest to open up the Gulf of Mexico to large-scale fish farming began, in a way, some 30 years ago on the black pearl diving docks of Micronesia. That’s where the Australian businessman Neil Anthony Sims first met the American marine biologist Kevan Main.

Their paths diverged – his to Hawaii to develop deep-water fish farming, hers to Florida to head the Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium in Sarasota – but the two remain key figures for a project that could transform not just the American dinner table, but also the economies of fishing ports from Alaska to Florida.

Velella Epsilon – the first fish farm in federal waters off the contiguous United States – would operate in the Gulf of Mexico, about 40 miles from Florida’s coast. Globe-shaped pens would hold fingerling almaco jack, a member of the amberjack genus, that would grow into 4-pound market fish within a year. If scaled with corporate investment, the project could eventually yield 64 million pounds of sushi-quality meat a year, enough to dramatically reshape the world’s seafood trade.

“People paying attention to the global impacts of humankind on the planet are saying we need more aquaculture, and offshore fish farms are a really scaleable, sustainable, low-impact form of aquaculture,” says Mr. Sims, the co-founder and CEO of Ocean Era, the company behind the Velella Epsilon project, in a phone call from Hawaii. “There’s deep water. You are further from shore. The currents are better. You work within the assimilative capacities of the system.”

As Velella Epsilon gains steam even under heavy regulatory headwinds, that phrase – “assimilative capacities,” the ability for the natural environment to safely absorb pollutants – will be key in a broader gambit for U.S. protein independence. At stake is whether markets and permits are enough to tackle the larger ethical questions about how to integrate fish farming into the complexities of a system that includes not just the Gulf of Mexico, but Americans who make a living off it.

“How much of the landscape and the seascape should human beings be using?” asks Philip Cafaro, a philosophy professor at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. “You have to be explicit about what your goals are. If it’s to maximize profits in the fishing industry, that’s one thing. If your goal is to maximize output to the fishing industry in order to protect communities, that’s a very different one.”

In a big pond

In 1986, the newly independent Federated States of Micronesia imported nearly 20,000 pounds of black-lipped pearl oysters, a species known for its high quality black pearls, and raised them in Chuuk Lagoon. At first, little was done to develop the fledgling republic’s nascent aquaculture.

But as Micronesia’s black pearl industry began to shift to a more managed model in the 1990s, “we saw a transition from hunter-gatherer to farmer,” says Mr. Sims. “And it took years of bitter fighting. But now those communities have reversed a brain drain because there are now millionaires in those communities.”

Mr. Sims’ goal off the coast of Florida is much the same, he says. “The primary driver behind Velella Epsilon is to showcase it to the fishing community as a great asset.”

It's now unclear which government agency has authority to approve the Velella Epsilon project, but which would test the feasibility of fish farming in a high-risk environment. It also represents the latest effort to push aquaculture through the regulatory maze that binds the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to eight regional fishery councils, which in turn set the rules for managing the wild stock.

The White House appears eager to open federal waters to aquaculture. With Executive Order 13921, President Donald Trump on May 7 ordered NOAA to winnow down regulations for both aquaculture and wild-caught fish. Last week NOAA announced that it would be creating 10 Aquaculture Opportunity Areas, including one in the Gulf.

But this push for open-ocean fish farming has faced legal hurdles. Earlier this month, a federal appeals court ruled that NOAA lacked the authority to take the lead in regulating aquaculture in federal waters, a victory for the environmental groups and fishing associations who brought the suit. Those groups have argued that open-sea aquaculture is too risky and too dependent on the market’s whims.

“A slice of the population looks at the oceans and thinks of them as a last, wild frontier, and to have farming in that last wild frontier is anathema to them,” says Paul Zajicek, executive director of the National Aquaculture Association in Tallahassee, Florida.

Ocean aquaculture is not without its environmental costs, such as escaped fish, parasites, and “fish sewage.” Though some of those problems are more endemic to near-shore fish farms, concerns remain among environmentalists and many Florida residents that deep-sea cultivation would prove even more complex, but with less oversight.

“It’s an ethical issue akin to raising tigers for consumption: You’re fishing up the food chain,” says Zach Corrigan, a senior attorney at the Washington-based nonprofit Food & Water Watch, which opposes the project. “I don’t think [Mr. Sims] represents what is really the best economic model for these fish farms, which is going to be cheaply produced fish out there on the fly. At that point you’re not competing against the imports, you’re producing expensive, high-grade product for your own dollars.”

Opening a can of worms

To James Bois, a commercial fisherman based here in Cortez, it’s unclear how a massive fish farm operation off the coast of Cortez will change his life. But he does know that unless Americans suddenly start consuming more seafood, his wild-caught fish – amberjack is on his list of allowable catch – will have to compete against Mr. Sims’ farmed almaco jack.

At the same time, fishing regulations deemed necessary to protect vulnerable stocks have reshaped Cortez. Today, the funky little slice of pre-Disney Florida is largely a bait fishery for larger fleet boats. If Mr. Sims began buying local bait to feed his fish, it could create a boom for Cortez, in the short term. Yet part of the plan to make open-ocean farming truly sustainable is to replace bait fish with a plant-based feed laced with algae oil. It takes 5 pounds of feed to build 1 pound of fish protein.

“Offshore farming can help us or hurt us. We don’t know which yet,” says Mr. Bois. “But one thing I know 100%: It will affect us.”

Market dynamics, court battles, and political battles seem far on the horizon from the Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium, on the outskirts of Sarasota. There, Ms. Main runs her marine workshop: tubs, PVC pipes, and notes on pH and salinity scrawled on wipe-boards. Ms. Main is the aquaculture scientist who solved the mystery of spawning snook. She helped pioneer pompano as a farmed fish. She has also farmed sturgeon and redfish.

Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium, Ms. Main points out, is not involved in the planning or operation of Velella Epsilon. But Mote has been contracted to provide some 20,000 fingerlings for the project’s initial cohort of fish.

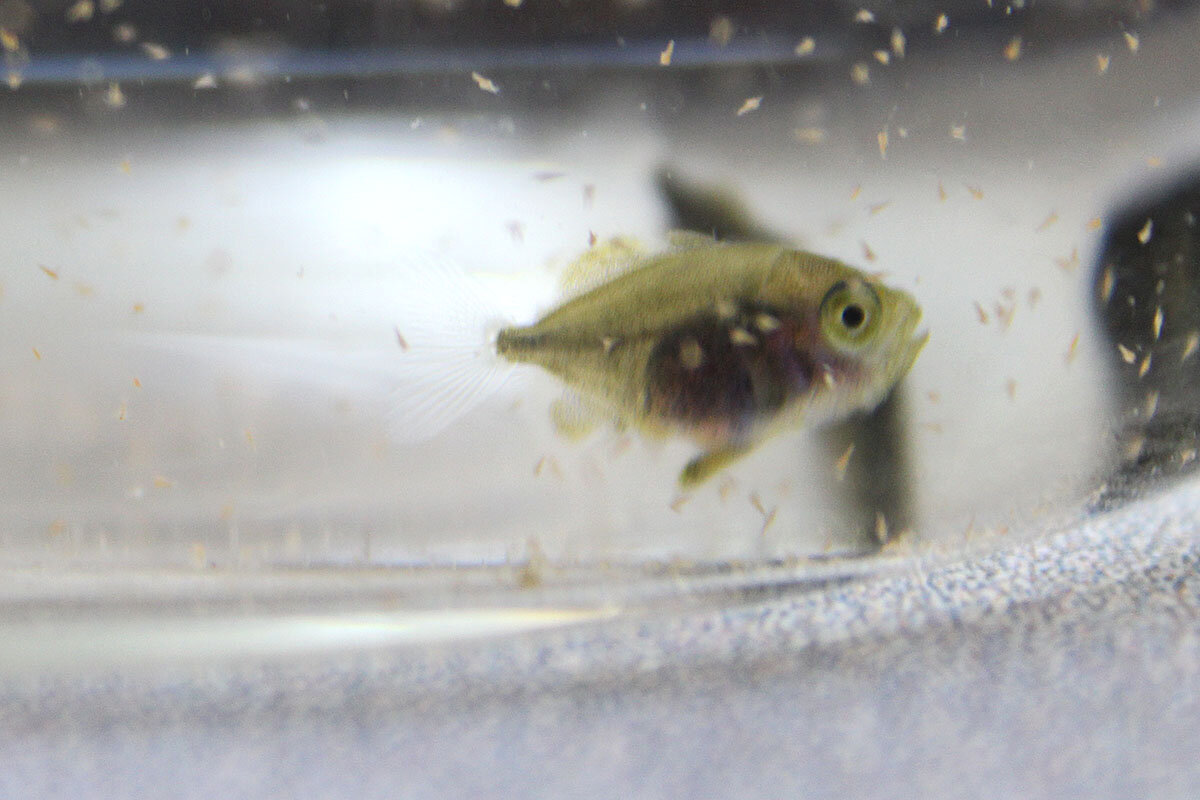

As she leans over a massive tank, she points to 28-day-old almaco jack fry gorging on brine shrimp. “Look at those little tiny row boats,” she says.

Indeed, her problems are far more immediate, given her hopes to have the demonstration pen operating by December. She is losing more of the almaco jack fry than she was expecting, forcing a reevaluation of the feeding plan.

But what’s harder to control than salinity is perception. In a way, how a dream to farm the open oceans clashes with shifting values on land is embodied by her work.

“We should be producing food that we eat in this country,” she says. “It’s really important, because we will do it right, it’ll be subject to our regulations, and we know what we’ll be getting.”

Black Britain’s biggest festival hit pause. But the music didn’t stop.

What happens when an identity-reinforcing carnival is made less robustly tangible by pandemic rules? It goes digital, sure. It also fires up enthusiasm for resumption next year.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Marthe van der Wolf Correspondent

The Notting Hill Carnival, held annually this month in West London, is the second-largest carnival in the world, attracting over a million people each year. The carnival showcases Black excellence, and celebrates and empowers Black beauty, in any shape or form. And it’s deeply rooted in the community, which is manifested by the many different generations that attend, organize, participate, and celebrate the carnival.

This year, like so many community events around the globe, the Notting Hill Carnival has been canceled due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Organizers instead held a “digital carnival” this past weekend. But in recent years, the official parade has featured more than 25,000 people dressed extravagantly, from colorful bikinis with feathers to mas, or costume, gowns, while performing in steel bands and dance groups on the elaborately decorated floats.

When Halina Edwards, who was born in Jamaica and raised in the Midlands of England, moved to London in 2014, the carnival felt like a warm bath full of community love. “It felt like a nice and safe place. But it’s also a moment to remind us why we’re here and the long history we have.”

Black Britain’s biggest festival hit pause. But the music didn’t stop.

When Josephine Julien arrived in Britain by boat from the Caribbean island of Grenada in 1956, she remembers encountering hostility from locals toward Black people. She saw written notices in the windows with slogans such as, “No Blacks, no Irish, no dogs.”

But Mrs. Julien was able to find a home in the Notting Hill neighborhood in West London, one of the few areas of the city where Black people could find apartments to rent.

So too, she says, were four young men who had formed a steel band on the same boat from Grenada. And in the 1960s, they went on to help start what was to become Britain’s largest annual Black cultural event, the Notting Hill Carnival.

Now, 54 years later, it is the second-largest carnival in the world, attracting over a million people each year. For Black Britons, even to those who aren’t of Caribbean heritage, the carnival showcases Black excellence. This is evident through the productions that take months of preparation and commitment. It also celebrates and empowers Black beauty, in any shape or form. And it’s deeply rooted in community, which is manifested by the many different generations that attend, organize, participate, and celebrate the carnival.

This year, like so many community events around the globe, the Notting Hill Carnival was canceled due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Organizers instead held a “digital carnival” this past weekend. It was the first time Mrs. Julien, now 82, couldn’t attend the Notting Hill Carnival.

But the event remains a fixture for her children, grandchildren, and most of the close to 600,000 people of Caribbean heritage in Britain. “It’s not only a celebration of our culture,” she says, “it’s our cultural heritage.”

Costumes and rhythms

There are varying personal accounts and narratives on the origins of the Carnival. It is generally believed there were several Trinidadian bands and masqueraders who paraded the streets of Notting Hill in those years. There was also an indoor Caribbean Carnival organized by human rights activist Claudia Jones in 1959, in response to rising racial tensions in London. Major incidents included rioting by white young men in Notting Hill in August 1958, and the murder of Antiguan expat Kelso Cochrane by three white men a year later.

This led to several initiatives being organized within the British Caribbean community that eventually all merged into what is now known as the Notting Hill Carnival. It is a celebration that is important to Mrs. Julien: “We have suffered a lot. This is the one time of the year we get to be openly proud of our culture and customs.”

In recent years, over 25,000 people dress extravagantly, from colorful bikinis with feathers to “mas” (costume) gowns, while performing in steel bands and dance groups on the elaborately decorated floats that form the official parade. The diverse and hyped crowds dance along with the soca beats blasting from the floats along the 3.5-mile route. The parade itself is surrounded by sound systems at different locations. The never-ending variety of Caribbean food stalls adds a flavorful barbecue smell to the festival. The cancellation means the city of London missed out on about $130 million that the weekend would have added to its economy.

But the cancellation of the parade due to COVID-19 doesn’t mean it will pass by unnoticed. Debi Gardner, who is of mixed Guyanese heritage and is a director of the carnival, says bands recorded their performances without an audience during the past month, which were broadcast during the online event.

Mrs. Gardner, who has a full-time job as a housing association manager, gives her entire life to the carnival and the community that goes with it. She plays with the famous Mangrove Steel Band, named after the West London restaurant known for its fight against racial injustice in the 1970s. She’s been a steel band player since the early 1990s and is also a part of their management team.

The band practices twice a week throughout the year and, pre-pandemic, used to travel all over to perform. “We also do a lot of activities throughout the year for young people, and within the creative arts,” Mrs. Gardner explains. “So not being able to do that has been disappointing.”

“It’s a moment to remind us why we’re here”

The pandemic may have put a temporary stop to the carnival, but it is not the only challenge that the event has been facing. Since its launch, media narratives around the carnival weekend have focused on crime and arrests. Organizers, participants, and attendees feel it is an unfair portrayal. Data shows incidents are comparable to festivals attended by a more white audience, such as the famous Glastonbury Festival. And Notting Hill is shifting toward a largely white and affluent demographic, one that is less keen about having the parade at their front doors.

Halina Edwards, who was born in Jamaica and raised in the Midlands of England, hopes that education can help remedy that. “In my school, we only had one lesson on Black history,” she says, “and they put on the movie Roots. I don’t think they realized how insensitive that was.”

This year, Ms. Edwards joined the social enterprise The Black Curriculum as a researcher, and hopes to contribute to changing the way Black people are represented and spoken about. The project focuses on delivering Black history programs for young people, and has created a magazine focusing on the Notting Hill Carnival.

When she moved to London in 2014, the carnival felt like a warm bath full of community love. “It felt like a nice and safe place. But it’s also a moment to remind us why we’re here and the long history we have,” she says. “If people had a better understanding of the context and the history of why it started there, they might understand there is a reason why we go onto the streets and celebrate this.”

It’s still too early to say if there will be a lasting impact on the carnival now that it’s not happening for the first time in its history. But change is inevitable, according to Mrs. Gardner, who has seen the carnival become a more diverse and inclusive event in the 25 years she’s actively been involved.

One thing is certain: The community cannot wait for 2021. Mrs. Julien walked around Notting Hill this past weekend to pay tribute to the long history of the carnival. “It’s not only us losing out when it’s not happening. The carnival has always been a bridge between different communities.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our pandemic coverage is free. No paywall.

Points of Progress

Where deforestation is in retreat

You probably noticed a current of solution orientation running through today’s Daily. We’ll leave you with this distillation of global progress – six short stories of reclamation, restoration, and justice.

Where deforestation is in retreat

1. United States

The Esselen Tribe of Monterey County has reclaimed ancestral lands in Northern California after closing a $4.5 million deal with Western Rivers Conservancy. The small tribe lived on the Big Sur coast and the Santa Lucia Mountains for thousands of years before Spanish explorers set up missions in the 1700s. For centuries, they’ve been landless.

The conservancy acquired 1,200 acres in Big Sur with the hope of finding an environmentally conscious steward. The property’s giant redwoods and river make it a key breeding site for two vulnerable species: the California condor and the south-central California coast steelhead. “We are going to conserve it and pass it on to our children and grandchildren,” Tom Little Bear Nason, tribal chairman, told The Mercury News. “Getting this land back gives privacy to do our ceremonies. It gives us space and the ability to continue our culture without further interruption.” (CNN, The Mercury News)

2. El Salvador

In a landmark case for transgender Salvadorans, three police officers have been found guilty of the 2019 murder of Camila Diaz. The court sentenced each officer to 20 years in prison for aggravated homicide, marking El Salvador’s first conviction for the murder of a transgender person. About 600 LGBTQ people have been killed in the conservative country since 1993, according to advocates, but the cases rarely go to trial and had never ended in a conviction.

Although the prosecutor’s office did not classify the attack as a hate crime, activists consider the ruling a major development for the country. “It sends a strong signal that anti-trans and more generally anti-LGBT violence is not going to be tolerated in the country,” said Cristian Gonzalez, a researcher at Human Rights Watch. (Thomson Reuters Foundation)

3. Costa Rica

Costa Rica is the first tropical forest country to stop and reverse its deforestation problem. In the late 1980s, as much as half of Costa Rica’s forests had been cut by loggers. Unlike its neighbors, the small Central American country has regrown most of the land. It did so by pairing a ban on deforestation with payments for ecosystem services, financed mainly by a fossil fuel tax. The program pays farmers to protect watersheds and biodiversity or capture carbon dioxide. Over the past 20 years, the government has paid $500 million to landowners, and it’s how many farmers in Costa Rica make an income. “We have learned that the pocket is the quickest way to get to the heart,” says Carlos Manuel Rodríguez, minister for environment and energy. (CNN)

4. Kenya

A Kenyan village led by environmental activist Phyllis Omido won a $12 million civil lawsuit accusing a lead-acid battery recycling plant of exposing the nearby community to lead poisoning. The money will be paid by government agencies found to be negligent and the directors of the since-shuttered smelting plant. Ms. Omido worked at Metal Refinery EPZ in 2009, but left after the company failed to acknowledge the troubling findings of an environmental impact assessment. Despite pressure – or outright threats – from co-workers, authorities, and family to drop the cause, she kept campaigning on behalf of families impacted by toxic waste smelting. At least 10 smelters have closed in Kenya as a result of Ms. Omido’s grassroots activism, and in addition to the $12 million payout, the judge has ordered the government to clean the affected community, Owino Uhuru, within four months. (BBC, CNN)

5. Botswana

Dozens of traditional leaders in Botswana will learn how to combat gender violence in their communities through a collaboration among Botswana’s government, the tribal administration, and the United Nations Development Program. In a country where nearly 70% of women have experienced physical or sexual abuse, experts say it’s essential to get buy-in from traditional leaders, who can then help other men unlearn bad habits and become better advocates for women. Chiefs like Puso Gaborone of the Batlokwa tribe will receive training on conflict resolution, addressing marital disputes, and reporting violent behavior. “No elements of traditional culture condone violence,” said Mr. Gaborone. “Dikgosi [chiefs] are essential stakeholders in addressing issues of violence in communities, and in bringing perpetrators to book.” (Thomson Reuters Foundation)

6. Thailand

Rare footage of three tigers roaming through a western Thailand forest is offering conservationists hope that the endangered species is making progress. This is the first sighting by the area’s camera traps in four years. There are an estimated 160 wild Indochinese tigers left in Thailand, where they face the threat of poaching, and the total global population may only be around 350, according to the World Wildlife Fund. There are about 3,900 tigers left in the wild, including the more widely known Bengal and Siberian tigers. “The next important step for us is that we have to try and make the connecting routes of each forest area accommodating for them, in order for the tigers to roam safely,” said Kritsana Kaewplang, country director for conservation group Panthera in Thailand. (Reuters)

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why Germany’s Merkel finds it hard to retire

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

When it comes to her style of leadership, German Chancellor Angela Merkel has long preferred to rely on values more than power – values like rule of law and respect for one’s opponents are her trademark. This approach has made Ms. Merkel the most admired democratic leader in the world. And as she prepares to leave politics in 2021, her leadership is in demand more than ever.

This year, crisis after crisis has tested the world’s most powerful woman. When the coronavirus struck, she coordinated an inclusive and firm approach across the Continent. With Mr. Putin, she has demanded transparency and accountability for the suspected poisoning of Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny. After a rigged election in Belarus, Germany pushed for transparency in the vote count and prepared to impose sanctions if the regime killed any more protesters.

“The world should thank the Germans – and ask them for more global leadership,” wrote Elisabeth Braw at a British defense think tank in April. True to her style, Ms. Merkel would probably not want such gratitude. She’s too busy doing good in Europe and for its neighbors.

Why Germany’s Merkel finds it hard to retire

When it comes to her style of leadership, German Chancellor Angela Merkel has long preferred to rely on values more than power. “You can’t solve the tasks by charisma,” she says. Nor, in the case of postwar Germany, by military force. Values like rule of law and respect for one’s opponents are her trademark. This approach has made Ms. Merkel the most admired democratic leader in the world. And as she prepares to leave politics in 2021, her leadership is in demand more than ever.

This year in Europe and along its borders, crisis after crisis has tested the world’s most powerful woman. When the coronavirus struck, she saw it as the “biggest challenge” in the European Union’s history and coordinated an inclusive and firm approach across the Continent. Then when the United States pulled out of the World Health Organization, Germany filled the void with new funding for the agency.

When Turkey challenged the maritime borders of EU member Greece over oil rights – threatening a war between the two NATO members – she forced deliberation between the two neighbors. When Russia escalated its military role in Libya, she was on the phone with Russian leader Vladimir Putin to quell the violence.

When the EU needed to borrow money to get Europe out of its pandemic recession, Germany set aside its aversion to debt and, as Ms. Merkel said, decided to put itself “in the other person’s shoes and consider problems from the other’s point of view.”

With Mr. Putin, she has demanded transparency and accountability for the suspected poisoning of Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny. As a defender of human rights, Germany airlifted Mr. Navalny to a Berlin hospital, confirmed that indeed he had been poisoned, and offered him asylum.

After a rigged election in Belarus, Germany pushed for transparency in the vote count and prepared to impose economic sanctions if the regime killed any more pro-democracy protesters. Ms. Merkel has warned Mr. Putin not to use force in Belarus. She has also stood firm in keeping sanctions on Moscow for its 2014 annexation of Crimea from Ukraine.

For all of the West’s woes with Russia, “we have to keep talking,” she told reporters Aug. 28.

Germany keeps showing respect to Russia even as it disagrees with it. Ms. Merkel has not ended the construction of a gas pipeline from Russia. And in a further move toward reconciliation, Germany is funding a center in St. Petersburg for citizens of both countries to record their memories of World War II and talk together about them.

“The world should thank the Germans – and ask them for more global leadership,” wrote Elisabeth Braw of the Royal United Services Institute, a British defense and security thinktank, in April. True to her style, Ms. Merkel would probably not want such gratitude. She’s too busy doing good in Europe and for its neighbors.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

When you need more faith

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Judith Hardy Olson

What can you do when you feel as though you don’t have faith? One woman shares a meaningful healing that taught her more about where faith comes from and how we can find it.

When you need more faith

When I was in my 20s, I got really sick. Our neighbor, a doctor, overheard my coughing and told my husband I should be in the hospital. My worried husband wanted to take me to the emergency room if I wasn’t better by morning.

I’d had other healings through prayer before, so all that long night I prayed. But I felt afraid and doubtful. My faith in everything that I believed felt sorely tested. I was no better as the sun came up, and I felt ready to throw in the towel. My faith didn’t seem enough, because I’d given this prayer thing all I’d got.

But then, I asked myself, “Have I really?” A quick inventory of my thoughts from the previous night showed that very few had been on the side of God’s love and care; most had been on the side of fear and doubt.

Right then I apologized to God for giving up, then added this P.S.: “But, God, there’s one thing I’ll never give up on – that You are Love. That, I’m sure of.”

Well, with that, it was as if the floodgates opened. Starting with that one tiny thing I had faith in, suddenly all the proofs I’d had of God’s loving care poured into my thoughts. In minutes, all the fear and doubt were gone. My fever was also gone. I felt filled with God’s love for me. I was able to get up, speak without coughing, and make breakfast for my family. And in a couple of days I was totally well.

I’ve learned in Christian Science that God is the origin of everything good, and we are created to reflect all of God’s goodness and love. We don’t generate it ourselves. So even what appeared to be “my” faith was really God’s faithfulness to me that I was reflecting right back to Him.

I learned more about this from my study of the Bible, where it says of faith: “It is the gift of God” (Ephesians 2:8). This means we all must have faith, even if we haven’t discovered it yet, because it’s God-given. And this steadfast trust has unlimited potential to lift us up and move us forward, because it’s sourced in the infinite God. “If you have faith as small as a mustard seed,” Jesus told his disciples, “you can say to this mulberry tree, ‘Be uprooted and planted in the sea,’ and it will obey you” (Luke 17:6, New International Version).

“God is Love” was my mustard seed. It started small, but it came to my rescue when my faith was tested. And it has continued to, in more instances than I can count.

Your mustard seed may be different, but it’s there, because it’s a gift God has given you that can never be taken away. And through God’s love you’ll find it – and it will grow.

Other versions of this article appeared in the Aug. 13, 2020, Christian Science Daily Lift podcast and in the Christian Science Sentinel’s online TeenConnect section, Oct. 8, 2019.

Editor’s note: Interested in reading more about faith as a powerful force for healing? Check out “Faith in your healing prayer,” an article on www.JSH-Online.com. There is no paywall for this article.

A message of love

Keeping watch

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow. We have reporters on the ground in Kenosha, Wisconsin, gathering local perspectives on the situation there. We’ll also have a powerful new episode of our “Perception Gaps” podcast, looking at the tension around America’s split takes on the main purpose of prison: Is it retribution or rehabilitation?