- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Rising from pandemic, the business success stories of tomorrow?

- At UN assembly quieted by a pandemic, the US-China clash is loud

- In Portland, a peaceful protest caravan rolls on

- Native American women shape how museums frame Indigenous culture

- During the coronavirus lockdown, some birds changed their tune

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Trump won’t commit to peaceful transition. How worried should US voters be?

President Donald Trump won’t commit to a peaceful transfer of power if he loses the election. He’s said that over and over in recent days, so it’s not a slip of the tongue.

Given that, how worried should voters be about the state of democracy in America?

First, some background. President Trump’s reason for his stance isn’t based on evidence.

Study after study has shown voting fraud isn’t a problem at the federal level. Mr. Trump’s own FBI director, Christopher Wray, told the Senate that just days ago.

“We have not seen, historically, any kind of coordinated national voter fraud effort in a major election, whether it’s by mail or otherwise,” Mr. Wray said.

Yet Mr. Trump insists that 2020 voting will be a “big scam” because of a rise in mail-in ballots due to the pandemic.

Second, there are weaknesses in the system the president could exploit. What if he leads in key states on Election Day, then Democratic mail-in votes begin to erode his margin? Baseless charges of fraud and attempts to shut down counting could cause a national political crisis.

But third, the odds are against this. If election trends are clear relatively early in the counting process there is much less chance that Republicans – or Democrats – could overturn a result by resorting to the courts or trying to appoint their own Electoral College electors, or some other questionable maneuver.

The “hanging chad” Florida election of 2000 was an aberration. The chance that 2020 hinges on a recount, with candidates only half a percentage point apart in one or more decisive states, is only 5%, according to FiveThirtyEight’s election forecasting model.

“The overwhelmingly likely outcome in November is that the winner will be recognized in short order and the margin will be great enough so that none of the loser’s fulminations will matter,” writes Daniel Drezner, professor at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, in The Washington Post.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Rising from pandemic, the business success stories of tomorrow?

Many businesses now struggle near the brink of bankruptcy, yet a surprising countertrend is visible: a faster pace of new-business formation than last year. History suggests that some of these employers may become long-term success stories.

Marissa and Adam Goldstein launched their business on Feb. 16, selling fashionable backpacks to adventure travelers. Less than a month later, when the pandemic hit, air travel and sales ground to a halt.

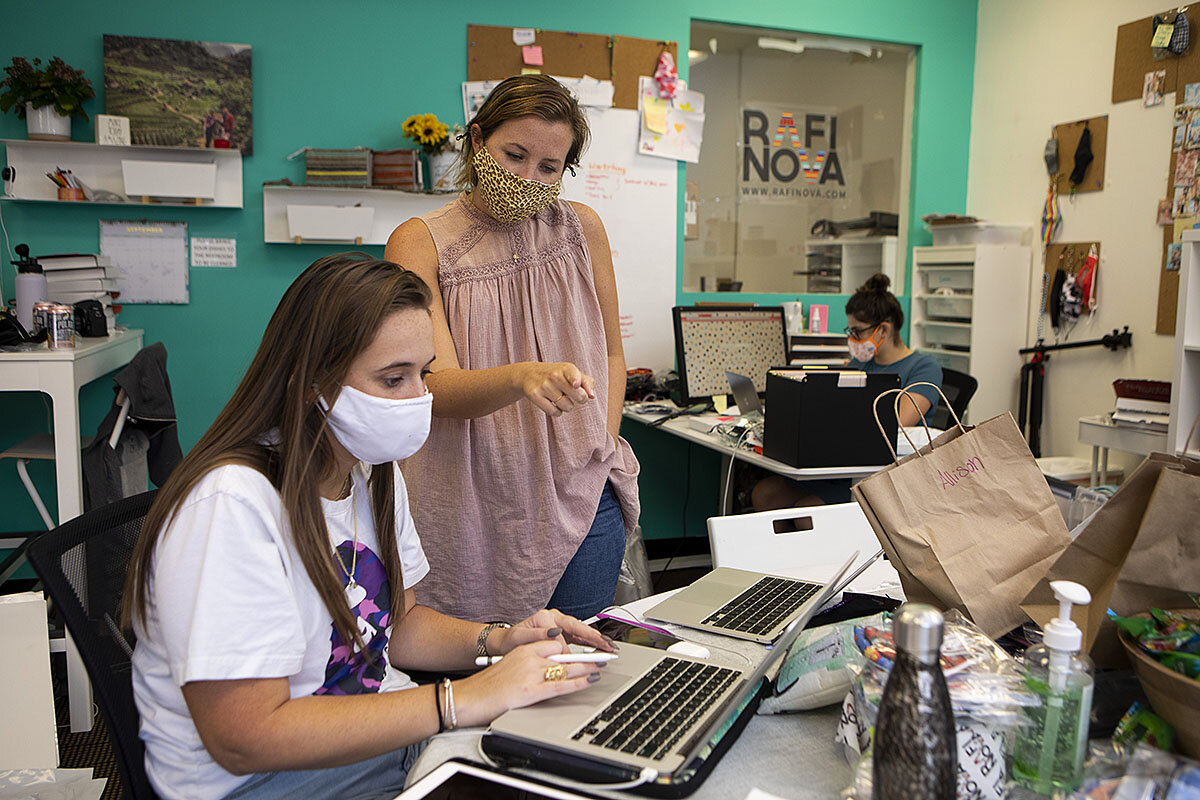

The couple decided they could at least put their Vietnamese factory partners to work making face masks that they could then donate to U.S. frontline workers. Then friends began asking for masks. When Ms. Goldstein put up a message on her website and Facebook page, saying “We have face masks,” she got $25,000 in orders by the next morning. Seven months later the firm, Rafi Nova, has 30 employees and is launching new products.

The pandemic has thrown many startups for a loop. More than a quarter of small businesses say they won’t survive more than three months; nearly 1 in 6 have considered bankruptcy, according to an August survey. Yet recessions, which kill off many startups, can also forge big winners. Over half of Fortune 500 companies were started during an economic contraction.

And amid the pandemic, the economy is on track to produce more startups in 2020 that are likely to hire workers, compared with last year. Says startup expert Marc Penzel: “A crisis always begets opportunity in more than one way.”

Rising from pandemic, the business success stories of tomorrow?

On Feb. 16, Marissa and Adam Goldstein launched Rafi Nova, a company selling backpacks for adventure travelers. Sustainably sourced, using textiles woven by Hmong women in Vietnam paid at a fair-trade rate, the backpacks might have been a thing. But the pandemic hit and domestic and international travel ground to a halt.

“Nobody was even leaving their house, let alone buying a $230 travel pack,” says Ms. Goldstein, whose business is in Needham, Massachusetts. “We probably launched a travel fashion company at the worst time in history.”

With few sales and no money left, the couple decided they at least could put their Vietnamese factory partners to work making face masks, which they could donate to front-line workers in the United States. “It wasn’t a business opportunity,” Ms. Goldstein says. “It was out of a sense of service.”

Then family and friends started asking if they could buy some of the masks. On a whim, Ms. Goldstein took a selfie of herself with a mask and put up a message on her website and Facebook page, saying, “We have face masks.” The next morning, she had $25,000 in mask orders and the company has never looked back. In seven months, the company has 30 employees in the U.S. and four more in Vietnam. Now expanding into additional products, the company will move to a new facility on Oct. 1, boosting capacity by 60%.

From Boston to Silicon Valley, the pandemic has thrown entrepreneurs a curveball like no other. Recessions usually crush fragile startups and convince many would-be entrepreneurs to hold off until times get better. But in the midst of this downturn, the number of new businesses in the U.S. is on the upswing. It’s not entirely clear why: Are entrepreneurs seizing on an opportunity – or just desperate because they just lost their job?.

“The crisis is unlike any other crisis we’ve seen before,” says Marc Penzel, founder and president of Startup Genome, an innovation policy advisory and research firm with offices around the world. “We’ve never had a situation where the economy had to shut down.”

The result is that entrepreneurs, instead of seeing a general contraction, are experiencing wildly different scenarios. Many entrepreneurs have found themselves in the wrong industry at the wrong time. And if Congress doesn’t provide additional emergency aid – its Paycheck Protection Program loan option for small businesses expired last month – more than a quarter of small-business owners say they won’t survive more than three months, according to Small Business Majority, a national advocacy group that surveyed its network of 70,000 businesses in August. Another 1 in 5 say they won’t make it past the next four to six months. Nearly 1 in 6 have already considered bankruptcy.

The dark clouds gathering around entrepreneurs are not unique to the U.S. In its global survey, Startup Genome found 41% of startups have three months or less of cash left, up from 29% before the pandemic. One reason is that downturns tend to accelerate existing trends, such as the move from on-site to online retail.

“You had businesses that were struggling already,” says Donna Kelley, professor of entrepreneurship at Babson College in Massachusetts and a member of the oversight board of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. “This was the final nail in the coffin.”

When he started his tourism company four years ago in eastern Kansas – not exactly a tourist mecca – Casey Cagle knew it would be an uphill climb. What he didn’t count on was the pandemic.

The lockdowns killed his spring season. When summer rolled around, he didn’t even bother trying to market the nearby Flint Hills and Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve to outsiders. Part of the reason was that he himself contended with an ailment in January that has hung on for months. Two tests say it’s not the coronavirus, but Mr. Cagle is taking no chances for his family or his clients. He’s staying at home – and home-schooling his daughter.

“It’s definitely a 180” turn, he says. “My mission before was to boost our local economy by bringing in people from the outside.” Now, he’s urging outsiders to shelter at home and not come – for their sakes as well as for his community.

Typically, business formation doesn’t pick up immediately when the economy begins to recover, says Professor Kelley of Babson. In the Great Recession it lagged for two years.

But after an initial plunge in March, the number of “high-propensity” business applications surged in May and for the year is running 12% ahead of last year’s pace, according to Economic Innovation Group (EIG), a Washington-based advocacy group. High-propensity applications are highly likely to become active firms with employees, according to the Census Bureau.

That would tend to rule out one reason for the surge: a flood of applications from suddenly jobless workers desperate to find something else – perhaps hanging out shingles as freelance workers. Another potential reason for the surge is that applications earlier in the year might have been backed up. But as the numbers have continued above last year’s levels, EIG has grown more optimistic: “Some of the surge may therefore represent the real thing: entrepreneurs finding opportunity in the crisis,” the group’s blog said this week.

The pandemic has actually helped some entrepreneurs. Already in April, when Startup Genome was surveying entrepreneurs worldwide, it found that 12% of startups had seen revenue rise by 10% or more. The paradox of recessions is that while they typically kill more than the usual number of startups, those that survive tend to be remarkably resilient. During the Great Recession, for example, transit giant Uber and mobile-payment platform Square were formed.

“A crisis always begets opportunity in more than one way,” says Mr. Penzel of Startup Genome. Over half of the Fortune 500 companies were started during a contraction and over 50 of them were created in the Great Recession alone, he says, and they are collectively valued at $145 billion.

While Bryanne Leeming was earning her MBA from Babson College, she was prototyping her idea of teaching children software coding through play. In 2018, she launched Unruly Studios, an education technology company in Boston. By 2019, the firm was selling to public schools its floor buttons, called Splats, which students can program to light up, make sounds, or collect points when they are stomped on. The idea is to teach coding skills through games. The first quarter of 2020 was the company’s best quarter yet.

When schools began to close in the spring because of the pandemic, the company’s team began talking to educators around the country about what they could use to teach online, in class, or in some hybrid model. As children were more isolated than normal during the summer, the company began focusing on strategies for improving social emotional learning. This fall, music teachers began to approach the company about using Splats for students to play music on, because the screens are easier to disinfect than the mouthpieces on recorders. The young company is rapidly approaching profitability.

“September already has been one of our best months yet,” says Ms. Leeming. “We have plans to accelerate this fall.”

The pandemic may well throw more curveballs. With the market for masks saturated, the Goldsteins are already steering Rafi Nova into new areas, offering belt bags and other mask accessories and copper-infused anti-microbial gloves. It will soon launch a line of apparel. The company gives away products and uses part of its profits to fund nonprofits.

“I never want to take advantage of the pandemic and the hurt and the suffering,” says Ms. Goldstein. “And so we try to create products that really help people like the masks and then take that a step further and make sure that our products can get into everyone’s hands, whether they can afford it or not.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

At UN assembly quieted by a pandemic, the US-China clash is loud

The United Nations is multilateralism institutionalized. Its annual General Assembly is one place global issues of common concern are tackled. Normally. What happens to such efforts in a pandemic? What is left?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The global pandemic turned the United Nations General Assembly this week in New York into a largely sad and dispiriting affair. Gone were the myriad bilateral meetings across a gridlocked Manhattan and the conference-room side sessions on the pressing issues of the day, from climate change to food security.

What’s left was a near-empty green-and-gold auditorium and a hear-a-pin-drop silence in hallways that normally would buzz with diplomatic chatter. And, more noticeably, the intensifying U.S.-China rivalry.

In his remote speech, Chinese leader Xi Jinping appealed to much of the world’s preference for cooperation over the go-it-alone, America-first approach espoused by President Donald Trump. Where Mr. Trump condemned the World Health Organization for helping China cover up the emerging coronavirus, Mr. Xi lauded the WHO’s “essential work” and pledged to boost China’s funding.

Amid talk this year of a new cold war, Europeans readily acknowledge that they too have their differences with China – but they add they prefer dialogue and diplomacy where possible.

“We have issues to discuss such as human rights. We are also competitors with China,” says a European diplomat on condition of anonymity. “We also want a level playing field and reciprocity. But if we want to face global challenges,” he adds, “we have to work together.”

At UN assembly quieted by a pandemic, the US-China clash is loud

It was supposed to be a grand celebration marking the 75th anniversary of the United Nations.

But the near-empty iconic green-and-gold auditorium, the absence of a parade of world leaders, and the hear-a-pin-drop silence in hallways that normally would be buzzing with diplomatic chatter in dozens of humanity’s rich languages – all attest to a sad and dispiriting U.N. General Assembly this week in New York.

The global pandemic – the first in the U.N.’s existence – felled much of what has made “UNGA” the preeminent global diplomatic gathering of the year. Instead of in-person speeches that gave national leaders great and small a turn at the marble dais, there have been prerecorded videos destined for an uncertain audience.

Gone, the myriad bilateral meetings across a gridlocked Manhattan and the conference-room side sessions that indicated to a global audience the pressing issues of the day, from climate change, nuclear proliferation, and migration to terrorism and food security.

No more intrigue on the order of what obsessed journalists from around the world last year: Would President Donald Trump run into Iranian President Hassan Rouhani? (He did not.) Or who would receive more applause, Mr. Trump or Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg? (Answer: Ms. Thunberg.)

The coronavirus pandemic has clearly dealt a blow to the “we’re all in this together” spirit that animates the U.N., and which has only grown in importance over recent decades as the world has increasingly globalized and confronted issues that know no borders.

Another blow to the U.N.’s multilateral underpinnings was struck by the heightened tensions and caustic rhetoric on display between the United States and China – the former the U.N.’s historical leader, the latter the rising superpower and pretender to America’s global leadership throne.

President Trump in his taped speech spoke of the “China virus” ravaging the globe – and for which he said Beijing must pay. In response, China’s ambassador to the U.N., Zhang Jun, rose to the dais in person before Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s taped speech to dispute Mr. Trump’s accusations and suggest instead that the U.S. president had introduced a “political virus” antithetical to the spirit of the U.N. to the global body.

Another 1945 moment?

Yet as gloomy and jarring as much of this year’s largely remote proceedings have been, there is also a hopeful sense that the world, coming together, can overcome the challenge of the pandemic, just as it fashioned a system of global cooperation out of the ashes of World War II.

As U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres noted in his address opening UNGA Tuesday, the world is at “another 1945 moment,” referring to the hinge year that saw both the end of World War II and the founding of the U.N.

“I heard that as Guterres being optimistic and aiming for the inspirational,” says Francine D’Amico, a professor of international relations and specialist in the U.N. and international institutions at Syracuse University. “I think he was saying the international community needs to act as it did in 1945, when it came together and established the first truly global institution.”

Instead, she adds, “many believe we are at a 1939 moment,” when the world fractured and marched off to a world war.

Mr. Guterres reassured his global audience that, provided the nations of the world together dip into the well of international cooperation and reject a resurgent nationalism, the world is up to the task of addressing the dire threats it faces.

That includes the pandemic. Noting that many of the globe’s best minds are racing to produce a COVID-19 vaccine in record time, Mr. Guterres warned against a “vaccinationalism” that would narrowly address the needs of some, largely in the world’s wealthiest countries, while leaving many in less-developed countries behind.

Talk of another cold war

Yet despite the hopefulness of pandemic-inspired cooperation, this year’s UNGA has laid bare the other challenge that very few were talking about a year ago, the rising tensions between the global body’s two biggest powers, the United States and China.

New this year is talk of another cold war, which many believe would undermine international cooperation and U.N.-led multilateralism farther into the future than COVID-19.

As French President Emmanuel Macron warned in his UNGA address, the mounting tensions between the U.S. and China threaten the U.N. with “impotency” at a time when multilateral action is essential to addressing global threats – from destabilizing regional conflicts and growing inequalities to the significant and varied impacts of climate change.

What worries many is that a U.S.-China cold war could cause a return to the inertia the international community experienced during the decades of the U.S.-Soviet Union standoff. “We’re seeing that the U.N. could very much be hamstrung as it was during the Cold War,” says Professor D’Amico.

European leaders in particular appear determined not to let rising U.S.-China tensions derail their efforts at safeguarding and promoting multilateralism despite an increasingly hostile global environment.

Pointing to the Franco-German alliance for multilateralism being advanced by Mr. Macron and Chancellor Angela Merkel, one European diplomat says, “We will continue to do that, whatever the situation is between the U.S. and China. We have no time to wait.

“We cannot remain in the margins and say, ‘It’s terrible, but we can’t do anything because the two big powers are having their discussions,’” adds the diplomat, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss openly the tensions at UNGA.

Europeans readily acknowledge that they too have their issues with China – but they add they prefer dialogue and diplomacy where possible over confrontation.

“We also have our discussions with China,” says the European diplomat, using a diplomatic replacement for “differences.” “We have issues to discuss such as human rights. We are also competitors with China. … We also want a level playing field and reciprocity. But if we want to face global challenges,” he adds, “we have to work together.”

Speaking the U.N.’s language

Mr. Xi in his speech deftly appealed to much of the world’s preference for cooperation over the go-it-alone, America-first approach espoused by President Trump. Where Mr. Trump condemned the World Health Organization for helping China cover up the emerging virus, Mr. Xi lauded the WHO’s “essential work” and pledged to boost China’s funding of the global health organization.

And where Mr. Trump blasted the “one-sided” Paris climate accords that he withdrew from in 2017, Mr. Xi announced a new commitment to make China carbon neutral by 2060.

Not that the world takes the Chinese word hook, line, and sinker. Indeed, Mr. Xi’s virtual audience on social media platforms was generally harsh, a kind of bottom-of-the-screen reality check highlighting China’s mass detention of Muslim Uyghurs and its strong-arming of Hong Kong.

But by and large Mr. Xi’s solidarity on the coronavirus, commitment to share globally any COVID-19 vaccine China develops, and special shoutout to China’s south-south dialogue and “commitment” to African partners, were all much more soothing to the U.N. ear than Mr. Trump’s nationalist rhetoric and America-first pandemic focus.

Mr. Trump did speak of America’s “destiny as a peacemaker” as he referenced the recent U.S.-brokered Serbia-Kosovo accords and normalization of relations between Israel and both the UAE and Bahrain.

But over all, what many observers have heard this week is a China stepping up to the leadership plate, and America pulling back.

“The U.S. chose multilateralism in 1945, and we were able to remake the world in our image, and in ways that served our interests,” says Professor D’Amico. “But now Trump’s theme seems not to be America as leader or partner, but more of an America-focused individualism,” she says.

One example: The U.S. effort this week to reimpose U.N. sanctions on Iran – a move even America’s closest allies have rejected as having no standing since Mr. Trump pulled the U.S. out of the Iran nuclear deal in 2018. Indeed, the administration is wearing its loneliness on Iran sanctions as a badge of honor.

As the U.S. ambassador to the U.N., Kelly Craft, said this week, America does not “need a cheering section to validate our moral compass.”

But neither can a superpower in withdrawal mode retain its global influence, others say.

“The problem is that if you’re not on the field, you can’t play the game, and you leave the field open to China,” Professor D’Amico adds. “If you walk away from the table, you have no say in who’s going to be calling the shots.”

In Portland, a peaceful protest caravan rolls on

There’s a different side to Portland protests than shown on TV. Our reporter joined a twice-weekly peaceful protest caravan organized by the grandmother of a teenager killed by police.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

You can hear the cars coming, hitting their horns to “Black Lives Matter!” On nearly every block, people come out to cheer the caravan on.

Twice a week, Donna Hayes and her best friend Jill Nicholson take their Portland protest parade to the streets, a different route each time to reach as many people as possible. They’ve been at it since June 12 and have no plans to stop. For them it’s personal. Ms. Hayes is the grandmother of 17-year-old Quanice Hayes. Her grandson was fatally shot by police in 2017.

Usually 40 to 50 drivers show up on Wednesdays and 70 to 100 on Saturdays. Adrienne Flagg, the logistical mastermind behind the rolling protest, says the caravan “normalizes” the message that Black lives matter. By going around different neighborhoods, “we’re bringing it to them, not just downtown.”

It can get tense. In August, a man in a truck blocked the group. Sylvia Dollarson, Quanice’s great-grandmother, got out of her car and approached. She asked him to stop; he reached for a gun and pointed it at her, she recalls. The episode was filmed and appeared on the local news.

But this great-grandmother is not giving up.

“I’m 77 years old. If I’m 107, I’ll still be driving if they haven’t made some changes.”

In Portland, a peaceful protest caravan rolls on

It’s dinnertime on a Wednesday evening, and so Donna Hayes and her best friend Jill Nicholson are leading a caravan of cars through otherwise quiet residential streets in northeast Portland, Oregon.

You can hear them coming, hitting their horns to “Black Lives Matter!” On nearly every block, people come out to cheer them on. A white man bangs a pot lid. A young Black man stops his bike and raises his fist. At one house, a mother steps onto her landing to wave, followed by two youngsters. Some residents yell “woo hoo!” at the cars, while others take videos.

Twice a week, the friends take their vehicle protest parade to the streets, a different route each time to reach as many people as possible. They’ve been at it since June 12 and have no plans to stop. For them it’s personal. Ms. Hayes is the grandmother of 17-year-old Quanice Hayes. Her grandson was fatally shot by police in 2017.

“We fight against police brutality,” she says simply, taping protest signs onto a red Prius before the cars roll out at 6 p.m.

Ms. Hayes has written a play, turned into a digital movie, “Silent Voices,” about nine people killed by police who return to tell their story.

This week, after news circulated that a grand jury had issued only one indictment, for “wanton endangerment,” in the killing of Breonna Taylor – and that not directly related to her death – many cars in the caravan displayed signs of her. The medical worker was fatally shot by Louisville, Kentucky, police in March during a botched raid on her apartment. “Say her name! Breonna Taylor!” drivers shouted from caravan bullhorns.

On Sept. 9, the caravan, hazard lights flashing, is on the small side. About 17 cars line up in a community college parking lot, as smoke builds from wildfires in the next county. Most of the participants are white, as is Portland itself. Usually 40 to 50 drivers show up on Wednesdays and 70 to 100 on Saturday afternoons. They demonstrate the consistency and determination that those pushing for racial justice say is necessary for change. In a pandemic, the caravan also allows those who may not be willing or able to take part in a mass in-person demonstration to do so.

Those would be people like Richard and Judi Seekins, married for 54 years, who have missed only one caravan since it started. They haven’t done anything like this since the Vietnam War.

“I’m a certain demographic, and I want people to know that all demographics in the community support this,” says Mr. Seekins, masked up and standing outside his white Toyota Prius before the caravan takes off. The couple is struck by the “amazing support” the caravan receives in each neighborhood, and Mr. Seekins quotes civil rights icon John Lewis about their “necessary” stand.

Those who protest peacefully and consistently are making people realize that “there is something to this,” says Mr. Seekins. He wants people to know that Portland is not on fire with violence or a city in chaos. At the same time, he’s distressed by “people who are taking advantage of this to make trouble.” They’re distracting from the original Black Lives Matter message, he says, causing the movement to “lose too much impact” right at a moment when the country may be at a “tipping point” toward greater racial justice.

Grace Julian is a college student and volunteer organizer with the group, which goes by the name PDX Car Caravan Protest. Were it not for the pandemic, Ms. Julian would be studying in Prague. Instead, she is home with her parents. She would have liked to have gone downtown to the protests this summer, but to protect her mother’s health, she did not think that was wise.

The caravan allows her to take part in the BLM movement. And she believes there’s power in consistent protest by “the little people.” It moves larger groups, like the National Basketball Association, which came to a temporary halt this summer. “That is big.”

“I’m learning so much,” she says. “I’m getting real world experience organizing people.” To make sure that her message includes action steps, she writes “vote.org” and a telephone number on her windows and signs.

Adrienne Flagg, the logistical mastermind behind the rolling protest, says the twice-weekly caravan “normalizes” the message that Black lives matter. By going around different neighborhoods, “we’re bringing it to them, not just downtown.”

Before the cars depart, she instructs a newcomer not to engage if someone tries to stop the group. “If one person is flipping you off, that’s their deal,” she says.

It can get tense. In August, a man in a pickup truck moved his vehicle back and forth across a neighborhood street to block the group. Quanice Hayes’ great-grandmother, Sylvia Dollarson, got out of her car and approached the man. She asked him to stop; he reached for a gun and pointed it at her, she recalls. Eventually, the caravan went around the pick-up truck and the man left. The episode was taped by a bystander and appeared on the local news.

But this great-grandmother is not giving up.

“I’m 77 years old. If I’m 107, I’ll still be driving if they haven’t made some changes.”

Native American women shape how museums frame Indigenous culture

Understanding women’s roles in Indigenous society can help draw a line from the past to the present. An exhibition in Chicago features the contributions of Crow, or Apsáalooke, women and proclaims: We are still here.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Richard Mertens Correspondent

Museums are increasingly turning to Indigenous peoples to represent themselves to the world, and with that movement has come a greater focus on women.

That shift in attention has highlighted underappreciated aspects of Native American culture, including the importance of communal ties, says Amanda Cobb-Greetham, a member of the Chickasaw tribe and director of the Native Nations Center at the University of Oklahoma. She contrasts the idea of “repatriation”– returning Native remains and sacred objects to the tribes from which they were taken – with “rematriation,” or the restoration and reassertion of core cultural values.

At the Field Museum in Chicago, “Apsáalooke Women and Warriors,” which opened earlier this year, tells about the Apsáalooke, or Crow, through their own eyes and their own stories. The exhibition uses examples of artistry to suggest how traditional beliefs and values have persisted and endure today. It shows the Apsáalooke reaching back to old ways of life and reinventing them in new circumstances and a new time.

“The women in my community are incredibly resilient, beautiful human beings who have managed to keep our community together in moments of devastation,” says Nina Sanders, guest curator for the Field exhibition. “They just shine.”

Native American women shape how museums frame Indigenous culture

Growing up on the Crow reservation in Montana, Nina Sanders learned some of her most valuable lessons not in school, where the textbooks were silent on her people and she was discouraged from speaking her native language, but at home with her grandmother and great-grandmother, listening to their stories and “tearing apart sinews, washing clothes outside, picking berries.”

Now Ms. Sanders celebrates the contributions of Crow, or Apsáalooke (Ahp-SAH-luh-guh), women in a major exhibition at Chicago’s Field Museum. “Apsáalooke Women and Warriors” paints a vivid picture of Apsáalooke history and culture, drawing on the Field’s extensive collections of Indigenous objects, including 19th-century ceremonial war shields, as well as on the work of contemporary artists, like rapper and fancy dancer Supaman. The result is rich and wide-ranging and proclaims unmistakably: We are still here.

Museums are increasingly turning to Indigenous peoples to represent themselves to the world, a movement that Ms. Sanders and others call the “decolonizing” of American museums. What sets Ms. Sanders’ exhibition apart is its focus on women, portraying them as keepers of culture and celebrating their devotion to family, clan, and homeland.

“The women in my community are incredibly resilient, beautiful human beings who have managed to keep our community together in moments of devastation,” says Ms. Sanders, a guest curator at the Field and the first Native American to curate a ticketed exhibition there. “They just shine.”

“Apsáalooke Women and Warriors,” open until July 18, 2021, and expected to travel after that, tells about the Apsáalooke through their own eyes and their own stories, beginning with their creation from the sea and continuing through their migration to the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains and eventual settlement on a reservation south of the Yellowstone River. The exhibition uses examples of Apsáalooke artistry to suggest how traditional beliefs and values have persisted and endure today. It shows the Apsáalooke reaching back to old ways of life and reinventing them in new circumstances and a new time.

The exhibition also reflects a transformation in museum practice and representation of Indigenous Americans that dates to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990. That act, itself a product of decades of activism, led to the return of remains and sacred objects and a new era of collaboration between museums and Indigenous peoples. It also inspired a shift away from portraying Native Americans as a vanished people toward emphasizing their contemporary culture.

The focus on women is more recent. Among the inspirations for Ms. Sanders’ exhibits were not only her childhood memories but also a recent, groundbreaking exhibition about Indigenous women artists, called “Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists,” at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Novelist Louise Erdrich said of that: “At long, long last, after centuries of erasure, Hearts of Our People celebrates the fiercely loving genius of Indigenous women.”

Paying more attention to women has highlighted underappreciated aspects of Native American culture, including the importance of communal ties, says Amanda Cobb-Greetham, a member of the Chickasaw tribe and director of the Native Nations Center at the University of Oklahoma. Ms. Cobb-Greetham, who is also a trustee of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, contrasts the idea of “repatriation”– returning Native remains and sacred objects to the tribes from which they were taken – with “rematriation,” or the restoration and reassertion of core cultural values.

“It redefines how we understand leadership, or significant achievement, and what values we want to carry forward,” she says. “That may or may not be military leader or government official. It may be something entirely different.”

One of the women portrayed in the Field exhibition is Sharon Stewart Peregoy, an Apsáalooke elder and Montana state representative. Though most Apsáalooke leaders have been men, including those in elected positions today, Ms. Stewart Peregoy says women have played a central role in helping the Apsáalooke endure decades of dramatic and often painful change.

“Through the transitions, especially with Native women and Crow women,” she says, “there was a need for everyone – and still today – to pull together, to participate, and with the ending of nomadic life and making the change to being put on the reservation, to be able to undergird our men, our warriors, quietly, not so quietly in some ways, but to get them to have hope again. That way of life died. But the woman says no, we can inspire to be more.”

Ben Pease is an Apsáalooke artist who contributed paintings and other works to the exhibition, including an oil painting that shows a procession of women on horseback, each wearing a gold halo. “We do believe as Apsáalooke people that women are holy and sacred beings,” Mr. Pease says. “They have the ability to give life and save culture and perpetuate culture into the future.”

Mr. Pease grew up in Lodge Grass, Montana, reared by “mothers and aunts and grandmothers,” he says.

“I learned the strength of women early on, and the role they play. In an underresourced and underrepresented community, they lead and are the great leaders to help us step into the future – but also to preserve the past, to be keepers of medicine and knowledge.”

The Field exhibition portrays the Apsáalooke as matriarchal and egalitarian. In one of the tribe’s stories, man and woman are created at the same moment. Rawhide war shields, decorated with owl feathers and dried bird heads, are displayed beneath giant images of women “to symbolically care for these shields,” a note says.

And yet beyond this, Ms. Sanders and her Apsáalooke collaborators invite viewers to reimagine what it means to be a warrior today and to perform the acts of bravery that traditionally distinguished the greatest Apsáalooke fighters. They pay homage to past warriors and leaders like Plenty Coups, Spotted Tail, and Joe Medicine Crow, an author and decorated veteran of World War II. But they also celebrate women – and men – who have become scholars, artists, and teachers.

“Nina tries to present a contemporary interpretation of what a warrior is,” says Ms. Stewart Peregoy. “That’s the idea – to get our young people to reawaken to their Native self, to their Crow self, and to what they can aspire to.”

“Apsáalooke Women and Warriors” opened in Chicago in March with a gesture to the past: a traditional Crow parade in which scores of Apsáalooke visitors, mostly women, walked in a line down city streets, some on horseback, and many more on foot, to the accompaniment of Apsáalooke singing and drumming. Ms. Sanders’ grandmother, Margo Real Bird, was among them. At a ceremony afterward, the pair stood arm-in-arm, a reminder of the bonds between past and present that Ms. Sanders wants to honor.

“It’s love,” she says. “It’s what transmits culture across time.”

Editor's note: This story has been corrected to reflect that Nina Sanders is the first Native American to curate a ticketed exhibition at the Field.

During the coronavirus lockdown, some birds changed their tune

The pandemic has forced a huge swath of humanity to drastically change daily routines. It turns out that nonhuman animals, too, are shifting their behavior.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

When the lockdown arrived in San Francisco, the city became muted. Traffic dwindled, crowds dispersed, fewer planes soared overhead, and the daily roar of industrial civilization receded to a murmur.

In its place came the birdsongs. The chirping and twittering were always there, of course, muffled by the sounds of the city. But now the songs were different. A study published yesterday found that white-crowned sparrows in San Francisco sang with a broader range, hitting the low notes once drowned out by cars and trucks. When the researchers compared the songs to archival recordings, they found that some of the birds were singing tunes not heard since the 1970s.

“These birds were filling the soundscape that was newly emptied of human noise,” says Elizabeth Derryberry, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and the study’s lead author.

The findings not only reveal how quickly certain birds can adapt to changing environmental conditions, but also illustrate the outsize influence that humans have on other animals.

To Allison Injaian, a University of Georgia biologist who was not involved in the research, the study presents “a great opportunity for all of us to realize the impact that we ourselves are having on the wildlife around us.”

During the coronavirus lockdown, some birds changed their tune

When the pandemic began, Elizabeth Derryberry wasn’t thinking about her research. Her focus was on the basics: how to teach remotely as an associate professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville; how to manage the lockdown with her young family; and how to keep everyone safe and healthy.

But as she scrolled through social media one evening, she saw a picture of a coyote at the empty Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. She recalls thinking, “Oh my goodness, there really are no cars.” And as she stared at that image, Dr. Derryberry thought about how quiet it must be nearby without the normal hubbub of traffic – and about the birds she had been studying there.

Along with her colleague David Luther of George Mason University, Dr. Derryberry had been recording the songs of white-crowned sparrows in both the urban setting of San Francisco and the more rural Marin County to study how the birds responded to the hum of human-made noise. They’d found that the city sparrows sang more loudly, but with a much more limited range, than their country cousins. And the shutdown presented an unprecedented opportunity for the researchers to see if those urban birds changed their tune.

Indeed, the urban sparrows took full advantage of the relative silence. When the research team recorded birdsongs near the Golden Gate Bridge in April and May of this year, they sounded notably different – and of higher quality – from those recorded during previous springs. Their findings were published Thursday in the journal Science.

“These birds were filling the soundscape that was newly emptied of human noise,” Dr. Derryberry says. “That was really exciting to see that kind of resilience.”

As people stayed home this spring, many noticed more wildlife around them. Some pondered whether there were actually more birds, for example, or if the quieter cities just made their songs (and presence) more obvious. Regardless, the shutdown yielded a renewed awareness that, even in the most densely populated cities, humans share the world with other creatures.

“When we’re going about our daily lives, we get used to the patterns of the animals that we see,” says Allison Injaian, a lecturer in the Odum School of Ecology at the University of Georgia, who was not involved in the study. “It’s pretty hard to know what we’re missing out on if that never is visible or audible.”

“But when this really unprecedented shift in human behavior occurred,” she says, it presented “a great opportunity for all of us to realize the impact that we ourselves are having on the wildlife around us.”

Softer songs in silent cities

Birdsongs are more than just friendly twittering in treetops. For the birds themselves, their songs encode information crucial to their existence.

White-crowned sparrows, for example, listen to each other’s songs to pick potential mates in spring, and as a way to assess the fitness of another male from afar when deciding whether or not to fight him to try to take over his territory.

But in cities, they’re typically making a trade-off between the quality of their songs and simply being heard, says Ken Otter, a biologist at University of Northern British Columbia who was not involved in the new study. “It’s like, ‘I can either make my song sound really awesome, but nobody can hear it or I can make it audible but make it sound [inferior],’” he says.

Before the shutdown, Dr. Derryberry and Dr. Luther found that birds in San Francisco were competing with nearly three times as much noise as those in Marin County. But when the pandemic closed everything down, there was no difference in noise levels. They attribute that to less traffic, as the amount of cars passing through had reverted to levels not seen since the 1950s.

As a result, birdsongs could travel much farther. The researchers found that the birds sang more softly because they didn’t have to be louder than the anthropogenic noise, and even still, their songs could travel twice the distance as before the shutdown.

The bandwidth of the trill at the end of the sparrows’ song is also key to communicating physical fitness to potential mates or rivals. Researchers found previously that the urban birds limit their trills to higher frequencies so they don’t have to compete with the low hum of traffic. But during the shutdown, the team found that the city sparrows utilized their full range – and when they compared the 2020 songs to historical recordings in the area, they found that some of the sparrows were singing in ways not heard in the city since the 1970s.

Whether this has a long-term effect remains to be seen, says Dr. Derryberry. But she plans to study the San Francisco sparrows’ sounds during the breeding season once again next year. “I’m really excited to see what happened with the nestlings that learned their songs this year,” she says. “What do they do? Do they keep those sexy songs? Do they modify them to transmit better as those noise levels go back up? Can they do that?

Adapting on the fly

Birds don’t just adjust their songs’ volume and range. Research has found that some urban birds will adjust the time of day that they sing to avoid rush hour.

“There are multiple strategies that birds can use to still be able to acoustically communicate,” Dr. Injaian says.

“And maybe that behavioral plasticity, that ability to change their behavior in this disturbed environment, allows them to evade any negative consequences. But we don’t necessarily know that yet. There might be negative consequences in the long term that haven’t shown up yet,” or perhaps it’s species-specific and other bird species are unable to cope with such noise at all.

Still, she adds, “One of the fascinating things about this study is that it shows that these birds are highly capable of acclimating to a new environment. We as humans changed our behavior, and we almost immediately saw a response in the behavior of these wild animals. And that, I think, can be a source of hope.”

Studies like this one, Dr. Otter says, can also help give us direction. “It’s really important for understanding how we can move forward with planning,” he says, “so that we can create spaces that not only attract the birds, but allow them to be successful.”

“We do have a sort of finite amount of space on the planet,” he adds, “and as we increase the amount of it that’s urbanized, what we really need to be conscious of is also making allowance for space for other organisms other than just people.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

An embrace of law to curb China’s bullying

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In a surprise move this week, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte reversed course and called out China for violating international law. He criticized it for not honoring a ruling by a United Nations arbitration panel that invalidated China’s vast territorial claims in the South China Sea.

The 2016 ruling, said Mr. Duterte in a video speech during the U.N. General Assembly, stood for “the triumph of reason over rashness, of law over disorder, of amity over ambition.”

Other Southeast Asian nations have lately rebuked China for intruding on their territorial waters and violating the 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea. These call-outs follow a U.S. decision in July to back the U.N. ruling.

All these actions come as China has aggressively pushed its territorial claims over Taiwan, the Himalayas, and Hong Kong. The pushback by Southeast Asians, notably the Philippines, reflects a collective effort to end a fear of Chinese threats and bullying and replace it with an affirmation of rules and law. The embrace of agreed principles may be the best defense against the use of brute force by China to extend its borders.

An embrace of law to curb China’s bullying

In a surprise move this week, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte reversed course and called out China for violating international law. He criticized it for not honoring a ruling by a United Nations arbitration panel that invalidated China’s vast territorial claims in the South China Sea.

The 2016 ruling, said Mr. Duterte in a video speech during the U.N. General Assembly, stood for “the triumph of reason over rashness, of law over disorder, of amity over ambition.”

Other Southeast Asian nations have lately rebuked China for intruding on their territorial waters and violating the 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea. In mid-September, Indonesia protested the intrusion of a Chinese coast guard ship in its exclusive economic zone. In July, Malaysia asserted that China’s maritime claims hundreds of miles from its shores have no basis under international law. Vietnam, a frequent victim of Chinese maritime harassment, has even hinted at defense cooperation with its former foe, the United States.

These call-outs follow a U.S. decision in July to back the U.N. ruling. The Trump administration also imposed sanctions on 24 Chinese companies that helped Beijing build artificial islands in disputed waters since 2013.

All these actions come as China has aggressively pushed its territorial claims over Taiwan, the Himalayas, and Hong Kong. The pushback by Southeast Asians, notably the Philippines, reflects a collective effort to end a fear of Chinese threats and bullying and replace it with an affirmation of rules and law.

“This isn’t a region that’s going to be subject to a Chinese Monroe doctrine,” said Alexander Downer, a former foreign minister of Australia.

The U.N. ruling, Mr. Duterte said in his talk, is now part of international law and beyond the reach of any government “to dilute, diminish, or abandon.” That embrace of agreed principles in law may be the best defense against the use of brute force by China to extend its borders.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Loving in the face of verbal violence

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Patrick McCreary

When a colleague’s recurring verbal attacks soured the work environment for himself and others, a stage manager turned to the Bible for help. As he learned more about what it means that God is Love, the situation turned around dramatically.

Loving in the face of verbal violence

Years ago, I was assigned to serve as stage manager for a major theatrical event. It was an extremely demanding assignment but a tremendous professional opportunity.

As the event dates quickly approached, the director began to increasingly yell and curse at the other staff and performers, including me. Now, having been raised in the Bible-based religion of Christian Science, I had to ask myself: Taking Christ Jesus’ example as a model for thought and action, how did this kind of behavior fit in? I realized that it did not, and so I searched the Scriptures for answers.

In First Corinthians, the Apostle Paul states: “Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal” (13:1). Many Bible scholars equate this use of the word “charity” with “love.”

Paul also speaks of the quality of love as including not behaving in an unseemly manner, not being focused on self, not allowing yourself to be provoked. And thinking no evil. Here he is giving us a road map for right reasoning and acting.

Was I willing to put this into practice myself, even in the face of this undeserved hostility?

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, drew inspiration from the Bible. In her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” she speaks of how we are protected from evil of every sort by learning to love: “Your decisions will master you, whichever direction they take. ...

“Stand porter at the door of thought. Admitting only such conclusions as you wish realized in bodily results, you will control yourself harmoniously” (p. 392).

I realized that I was not “standing porter” over my thinking, but just going along and hoping that I wouldn’t be the object of verbal violence. So I asked myself: Am I really seeking to love loving? Do I honestly love my friends and my so-called enemies? Am I satisfied with expressing anything less than a Christly, loving spirit?

God, alone, is Love. And divine Love is the only legitimate power governing all His children. We don’t need to search about for God’s love. God is All, and God is Love, so all must be Love, and there can be nothing unlike this ever-present Love.

Needless to say, this doesn’t always seem to be the case. But it is our job to identify this as the spiritual reality, to accept divine Love as our sole source of inspiration – and then we’re equipped to demonstrate the largess of that Love in our daily thoughts and deeds.

I resolved to seek an uplifted sense of affection for my co-workers – including the director – as fellow children of God, not stressed or angry mortals. Instead of trying to avoid the director, I welcomed his presence, respected his position, and strove not to personalize any unwarranted criticism, affirming that both he and I were surrounded, supported, and supervised by Love alone.

Soon, I felt a great release from stress, and my many tasks became less labored. I found that I truly wanted to be there and discovered a newfound sense of excitement for the creative challenges. The director’s demeanor dramatically changed, too. He became supportive, complimentary, and encouraging, a change noted by many.

Mrs. Eddy shares in her “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896”: “In Christian Science, the law of Love rejoices the heart; and Love is Life and Truth” (p. 12). What a great guide divine Love provides in confidently and joyfully meeting the needs of every moment!

A message of love

May her memory be a blessing

A look ahead

Come back Monday, when we’ll have a profile of Joe Biden by our Washington bureau chief, Linda Feldmann. Is not being Donald Trump enough to win?