- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Is there room for empathy in politics?

Noelle Swan

Noelle Swan

Why does empathy matter?

In my time as science editor, I’ve seen political trench digging around climate change. But I’ve also seen how empathy can turn battles into conversations. When we start to explore the experiences and fears that fuel the intensity of this debate, these two warring factions come into focus as people.

Presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin says empathy has been essential for many presidents too. Her 2018 book, “Leadership: In Turbulent Times,” focuses on the role of empathy in the presidential administrations of Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, and Lyndon Johnson. Each came to power at a time of “unprecedented” partisanship, not unlike today. And each employed empathy as a guiding light through dark times.

That spirit of compassion was on display in Illinois during the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858. Lincoln was trying to unseat incumbent Sen. Stephen Douglas. A staunch abolitionist, Lincoln denounced slavery, but he stopped short of writing off the people who supported it.

“I have no prejudice against the Southern people,” he said. “They are just what we would be in their situation.”

Empathy played a role in the success of Franklin Roosevelt’s fireside chats during the Great Depression. He explained policy decisions, but he also showed voters that he understood their worries and he enlisted their help. “Let us unite in banishing fear,” he implored in his first such address on March 12, 1933.

Then, as now, it was difficult for Americans to imagine common ground. But it’s worth remembering Roosevelt’s closing remarks from that first fireside chat: “Together we cannot fail.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Trump’s taxes: a question of leadership, not just legality

Using available loopholes to avoid taxes may be a time-honored tradition. But it can be risky politics, as citizens look to leaders to model financial integrity.

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

After years of resisting calls to release his tax returns, Donald Trump is suddenly facing new public scrutiny of his finances. According to tax records obtained by The New York Times, Mr. Trump paid no federal income taxes in 11 of 18 years examined, as deductions and claimed business losses offset income.

The Times’ report also concluded that during the Trump presidency, the Trump firms have received more money from foreign sources than previously made public. Hundreds of millions of dollars in loans personally guaranteed by the president will come due soon – as the IRS continues to audit a $72 million tax refund Mr. Trump has already received.

President Trump is not shy about congratulating himself as a successful businessman, and has boasted about his affinity for debt and ability to take advantage of tax loopholes, which he has said makes him “smart.”

Whether Mr. Trump violated laws is not yet clear. But tax experts say that presidents have a special role as example-setters in a system of voluntary compliance for supporting a shared government. “The extent of his avoidance is remarkable,” says Vanessa Williamson, a senior fellow at the Tax Policy Center.

Trump’s taxes: a question of leadership, not just legality

“Make sure you pay your taxes,” Richard Nixon told the British journalist David Frost in a 1977 interview. “Otherwise you can get in a lot of trouble.”

The former president knew this from bitter experience. During his first term he took big deductions that looked bad when leaked to the press. President Nixon lost half his net worth before the scandal subsided.

Now President Donald Trump is getting a lot of attention for big deductions – and other tax-reducing financial maneuvers – that have been leaked to the press. A huge New York Times story covers over 20 years’ worth of President Trump’s personal financial records.

His situation is far from analogous with Nixon’s, of course. His taxes may seem startling to an average American – he paid only $750 in income tax in 2017. But it remains unclear whether he did anything illegal, or even unusual for wealthy owners of commercial real estate.

However, in one sense the two cases may be similar: the question of leading by example. When it comes to tax loopholes, are presidents ordinary citizens who can fight for every advantage? Or should they treat their tax obligations as symbolic of their character and attitude toward the business of American government as a whole? In their first years as president, Barack Obama paid $1.79 million in taxes, while George W. Bush paid $250,000.

U.S. presidents are both the taxpayer-in-chief and the tax-collector-in-chief, says Joe Thorndike, a tax historian and expert who’s written extensively on the Nixon case. They sit at the top of a system that, in the end, relies on voluntary compliance. The faith of citizens in its integrity matters – a lot.

“We depend on people being honest, and it’s important to know the president is honest too,” says Dr. Thorndike.

“Extent of his avoidance is remarkable”

The trove of tax information received by the Times represents the clearest and most extensive available picture, by far, of President Trump’s tax obligations and the financial structure of his companies.

Overall the president paid no federal income taxes in 11 of the 18 years Times reporters examined. His incoming cash was more than offset by a gusher of claimed losses at his golf courses, Washington hotel, and other businesses, as well as deductions for business expenses.

Among the details: Mr. Trump’s firms appeared to pay more than $20 million in (deductible) consulting fees to his adult children, who in some cases were already employees of those firms. Personal expenses claimed for deductions include more than $70,000 paid out for hairstyling during Mr. Trump’s stint on “The Apprentice.”

During the Trump presidency, the Trump firms have received more money from foreign sources than previously made public. Hundreds of millions of dollars in loans personally guaranteed by the president will come due soon – as the Internal Revenue Service continues to audit a $72 million tax refund Mr. Trump has already received.

In general, it looks like the president and his companies have taken aggressive tax positions, says Mark Mazur, director of the Tax Policy Center. They also blur the line between personal and business expenses, which can be a red flag for the IRS.

“It’s surprising to see example after example where that was the case,” he says.

It’s not unusual for real estate investors to have low or negative tax rates, due to the debt they incur to invest in their businesses and the pattern of incoming rents and outgoing expenses, says Dr. Mazur, a former assistant secretary of tax policy at the Department of the Treasury.

“But what’s different here is the scale. It’s not a little bit, it’s a lot,” he says.

President Trump is not shy about congratulating himself as a successful businessman, and has boasted about his affinity for debt and ability to take advantage of tax loopholes, which he has said makes him “smart.”

“But the extent of his avoidance is remarkable,” says Vanessa Williamson, a senior fellow at the Tax Policy Center and author of “Read My Lips: Why Americans are Proud to Pay Taxes.” “The precision with which he has produced tax avoidance through losses of money is really extraordinary.”

But just because something is carried out on an unprecedented scale does not mean that it is de facto illegal.

The size of President Trump’s business losses and the fact that they have continued to occur year after year may be highly unusual, say conservative defenders of the president. But he’s only doing what lots of wealthy people do when they plan to minimize their taxes. The U.S. tax code is extremely complex and continues to be riddled with loopholes and other ways to avoid paying Uncle Sam.

In that sense the president’s tax returns may be a window into the nature of the nation’s financial system as much or more than revelations about Mr. Trump’s own planning.

“I think most people understand that this practice is common,” says Daniel Weiner, deputy director of the Brennan Center for Justice's election reform program. “And frankly these sorts of loopholes in our tax code are ultimately a product of much deeper dysfunction in our democracy.”

A post-Nixon tradition: releasing tax records

In the 1970s Nixon tried to make a big deduction through an existing loophole that had been used only for small deductions in the past.

He released his tax returns in late November 1973, following a grilling on his personal finances and the developing Watergate scandal by newspaper editors at a question-and-answer session at Walt Disney World. (It was during this session that he made his famous remark, “People have got to know whether or not their president is a crook. Well, I am not a crook.”)

The returns revealed that Nixon had claimed a $576,000 deduction based on the perceived value of a charitable donation of his vice-presidential papers to a government archive. For 1970 this reduced his tax liability to $792.81.

The deduction was legal at the time. President Dwight Eisenhower had done the same. But the drastic tax reduction became controversial, and Nixon had backdated the donation in error. An investigation showed he owed a considerable amount in back taxes, which he paid, at a high cost to his net worth.

In 1976 candidate Jimmy Carter released his full tax returns to bolster his image as a plain man of the people. He won – and releasing returns became a norm and ritual for presidential nominees, until candidate Donald Trump declined to follow suit.

The exposure of any potential conflicts of interest is not the only reason that norm was important, says Vanessa Williamson of the Tax Policy Center. It was also about setting an example.

“You do that because elected officials should represent a higher virtue in their dealings than just the average,” she says.

After all, the entire U.S. tax system relies on taxpayer self-assessment and rule-following. Few returns are audited. Most Americans are willing to pay their fair share if they think others are (roughly) paying a fair share too.

Blatant tax cheating by elites can collapse this social compact. Look at Greece, where widespread political corruption over the years fed a culture of tax avoidance that costs the government substantial revenue.

“At a time when often the American people are expected to pay taxes, including to support many things that they might not individually agree with whether it’s wars or expansive social programs, a person who is at the head of our government arguably should be setting an example,” says Mr. Weiner of the Brennan Center.

Are Amy Coney Barrett’s religious views fair game?

Some see the Constitution’s “no religious test” clause as preventing such inquiries. But others say asking about how religion shapes a nominee’s outlook isn’t necessarily discriminatory – and is, in fact, vital.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Are Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett’s religious views fair game? The former Notre Dame professor encountered a lot of pushback over her conservative Catholic background in 2017 when President Donald Trump nominated her to be a federal judge. Now the stakes are higher. If confirmed, Judge Barrett would become the sixth Catholic on the nine-member Supreme Court, and cement a two-thirds conservative majority that could rule on hot-button issues from abortion to “Obamacare” to the rights accorded LGBTQ individuals.

While Senate Democrats will no doubt scrutinize Judge Barrett’s judicial record, they have been careful so far to avoid any appearance of an attack on her religious beliefs this time around.

The U.S. Constitution prohibits religious tests as a qualification for federal office. However, some argue that the clause does not ban senators from considering the influence a judicial nominee’s religious views might have on her work, just as they would also consider other views relevant to their work. “Judges don’t come to the bench as blank slates,” says Richard Garnett, a longtime colleague of Judge Barrett and a professor of law at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

Walking that line in today’s fraught political environment is tricky, however.

Are Amy Coney Barrett’s religious views fair game?

President Trump’s Supreme Court nomination of Amy Coney Barrett, a federal judge and former standout Notre Dame law professor, has set the stage for a high-stakes confirmation process.

Nominating anyone five weeks before the election would have been controversial. But Judge Barrett’s conservative Catholic background and membership in the People of Praise, a tightknit charismatic community, has raised particular concern on the left, despite liberal colleagues praising her as a brilliant legal thinker. If confirmed, she would cement a two-thirds conservative majority on a court likely to consider hot-button issues from abortion to “Obamacare” to the rights accorded LGBTQ individuals. While likely to scrutinize her judicial record, Senate Democrats have been careful so far to avoid any appearance of an attack on Judge Barrett’s religious beliefs after being criticized for doing so in her 2017 confirmation hearings to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit.

The U.S. Constitution includes an explicit prohibition on religious tests as a qualification for federal office, including judicial posts. However, some argue that the purpose of that clause is to protect against a practice then applied in England to keep Catholics out of government, and does not obviate the importance of considering how a judicial nominee’s religious views might shape the way she carries out her duties. Walking that line in today’s fraught political environment is tricky, however, particularly given that religion is increasingly seen as a partisan issue.

“Judges don’t come to the bench as blank slates – we’re all human beings,” says Richard Garnett, a professor of law and political science at Notre Dame University in Indiana, where he directs the Program on Church, State & Society.

“I think it’s appropriate to ask about beliefs and views generally, so you could include religious beliefs among those, so long as they are not singled out for particular suspicion,” says Professor Garnett, who has known Judge Barrett since she and his wife were clerks together on the Supreme Court.

However, he adds, it’s important that the nature and purpose of those questions is focused on clarifying that the judicial nominee understands the role of a judge is to decide legal questions, not policy or religious questions. “What’s not appropriate – and this happened to some extent last time around, in my view – is to single out religious nominees, or for that matter, nominees from a particular religion, and to suggest that their particular religion makes them somehow unusually suspect.”

The last time around was in 2017, when the Senate considered President Donald Trump’s nomination of then-Professor Barrett as an appeals court judge. Democratic senators, most notably Sen. Dianne Feinstein of California, raised concerns about how her faith would shape her interpretation of the law.

“Why is it that so many of us on this side have this very uncomfortable feeling that, you know, dogma and law are two different things and I think whatever a religion is, it has its own dogma,” said Senator Feinstein. “The law is totally different and I think in your case, professor, when you read your speeches, the conclusion one draws is that the dogma lives loudly within you. And that’s of concern when you come to big issues that large numbers of people have fought for years in this country.”

Some saw such questions as reminiscent of anti-Catholicism attitudes prevalent in earlier years, as well as a violation of the Constitution. Article VI states, “The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the Members of the several State Legislatures, and all executive and judicial Officers, both of the United States and of the several States, shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.”

This is the only explicit reference to religious liberty in the original Constitution, before the First Amendment was added as part of the Bill of Rights several years later in 1791. Although the clause received unanimous support at the Constitutional Convention, it became a controversial topic during ratification, with some Americans considering it “too risky” to allow Catholics or non-Christians to hold office.

“No religious test” in spotlight

The “no religious test” clause has received more attention in recent years, particularly after several religious judicial nominees, including William Pryor, faced resistance in their 2003 hearings. A 2007 Harvard Law Review article argues that the clause “does not forbid officials – or the general citizenry – from considering or even inquiring into an individual’s religious beliefs when deciding whether to nominate, confirm, or vote for the individual.”

Jud Campbell, an associate professor of law at the University of Richmond School of Law who specializes in First Amendment law and constitutional history, agrees that there is no constitutional limit on questions about a judicial nominee’s religiosity. However, he urges caution not only in questioning religious nominees about how their religiosity would affect their interpretation of the law, but also in questioning LGBTQ nominees about how they would handle cases with LGBTQ litigants, or Black judges dealing with Black litigants.

“Obviously those sorts of questions have the capacity to be deeply harmful to the sort of inclusivity that we want to promote as a people and a constitutional culture,” says Professor Campbell. “Those are not the sort of questions that white male Protestants get.”

One reason that white male Protestants don’t get those questions very often in Supreme Court confirmation hearings is that only two have been nominated in the past 30 years – David Souter, who served from 1990 to 2009, and Neil Gorsuch, who was baptized Catholic and went to Jesuit schools but now identifies as Episcopalian.

A majority Catholic bench

Mr. Gorsuch sits on the court with two Jewish justices and five Catholic justices, including Obama nominee Sonia Sotomayor. Judge Barrett would make the sixth Catholic on the nine-member court in a country where Catholics make up about 20% of the population but play an outsize role in the conservative legal movement. Leonard Leo, co-chairman of The Federalist Society and a member of the Knights of Malta, a Catholic order, has been credited with spearheading a surge in Catholic Supreme Court justices in recent years, according to a profile in The Daily Beast.

“In this country, having six or almost seven judges Catholic at the same time when this country is becoming less Christian, more secular ... I believe Catholics should behave responsibly and at least do something to reassure [Americans] that this is not part of a theocratic or integralist project,” says Massimo Faggioli, a relatively liberal Catholic theologian at Villanova University in Pennsylvania. “I can understand why non-Catholics are not asking that question, because they don’t want to be accused of being anti-Catholic.”

Even Professor Faggioli has come under fire as anti-Catholic for raising what his critics characterized as old tropes about dual loyalties in a Politico column last week. In the piece, he encouraged the Senate Judiciary Committee to examine Judge Barrett’s reported connection with the People of Praise and any impact her commitment to the group may have on her spiritual and intellectual freedom.

People of Praise is ecumenical but largely comprised of Catholics and is part of a broader movement of charismatic groups that have sprung up in the past few decades. According to the group’s website, after three to six years of instruction and participation in the community, members make a lifelong commitment, or covenant, to their fellow worshippers and to God. The group has come under particular scrutiny for following the admonition of St. Paul that wives should be subservient to their husbands, as well as for leaders’ reported influence on personal decisions such as dating and marriage.

Judge Barrett does not appear to have directly addressed her involvement in the group, though in her acceptance speech on Sept. 26 she made a point of noting that her kids all thought her husband – a lawyer in private practice – was the better cook.

With President Trump looking on in the Rose Garden, she paid tribute to Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the liberal icon and women’s rights defender whom she would be replacing, calling her “a woman of enormous talent and consequence, and her life of public service serves as an example to us all.” Judge Barrett also highlighted the warm friendship that her own mentor and former boss, the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, had shared with Justice Ginsburg, despite their differing views.

Judge Barrett did not mention her own faith at all in her speech. But when asked by then-Sen. Orrin Hatch in her 2017 confirmation hearings how she would respond to Democrats’ concerns about the impact of her faith on her judicial decisions, she replied: “Senator, I see no conflict between having a sincerely held faith and duties as a judge.”

“And were I confirmed as a judge, I would decide cases according to the rule of law from beginning to end,” she continued.

And what of issues on which the Roman Catholic Church’s position differs from that of the law? Nearly two decades earlier, as a Notre Dame law student in 1998, then-Amy Coney co-authored a law review article on whether Catholic judges should recuse themselves from presiding over cases involving capital punishment, which is opposed to the church’s teachings. The article, which also mentioned other areas of potential conflict such as abortion, concluded, “Judges cannot – nor should they try to – align our legal system with the Church’s moral teaching whenever the two diverge. They should, however, conform their own behavior to the Church’s standard.”

“In the rare circumstance that might ever arise – I can’t imagine one sitting here now – where I felt that I had some conscientious objection to the law, I would recuse,” she told Senator Hatch and his colleagues. “I would never impose my own personal convictions upon the law.”

The Senate approved her nomination 55-43, with two Democrats – Joe Donnelly of Indiana and Joe Manchin of West Virginia, both of whom are Catholic – joining the Republican majority.

This time may be harder.

In Iran, outrage over patriarchy spurs change

How does change come to a traditional society? In Iran, a lenient sentence for the murder of a 14-year-old girl and the removal of girls’ images from a math textbook are fueling anger at the patriarchy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The tug of war over the role of women in Iranian society – a battle that has been going on since the Islamic Revolution in 1979 – has taken a new turn.

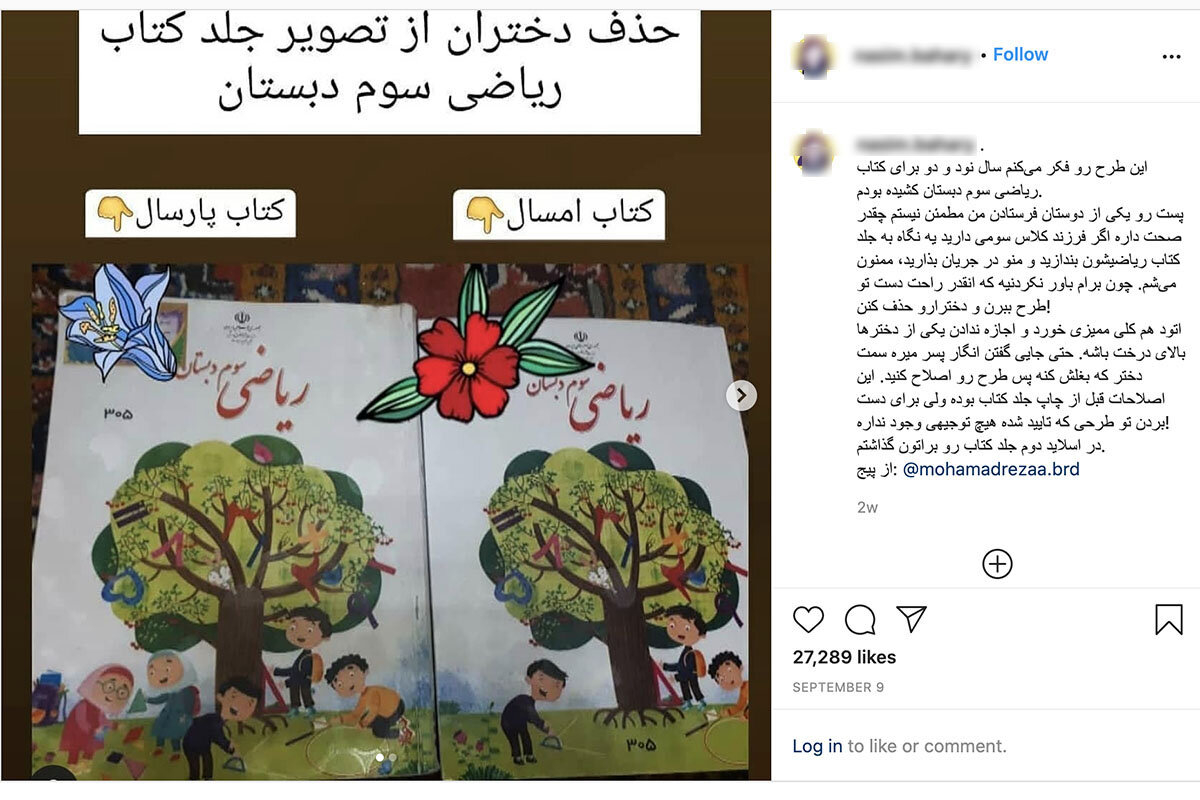

A recent court ruling, sentencing a man to just nine years in jail for the “honor killing” murder of his daughter, sparked unusual public outrage. (A woman was recently imprisoned for 15 years for removing her head covering in public.) Then parents ridiculed the Education Ministry for removing two girls from the cover of a third grade math textbook, leaving only boys in the illustration.

Such was the level of anger at the girl’s murder that parliament finally passed a law against child abuse that had been stalled for 11 years, and it is moving on a bill to criminalize violence against women.

“There is an emerging and fast-growing trend among different layers of the Iranian public to demand answers and accountability,” says a sociology teacher in Tehran.

In Iran, outrage over patriarchy spurs change

First there was popular outrage in Iran over the sentence handed down to a farmer who killed his own 14-year-old daughter, Romina, in a so-called honor killing.

Last month the father was sentenced to just nine years imprisonment for the murder, despite calls from even hidebound Iranian conservatives for “severe” punishment.

Then popular anger was stoked again when third grade math books were handed out in classrooms this month. The cover image had been modified – removing two girls but leaving three boys – because from an “aesthetic and psychological point of view,” the Ministry of Education said in a statement, the scene was “overcrowded.”

The two episodes have shone fresh light on systematic gender discrimination in Iran, and the popular outcry has forced change on the ruling elite.

They are the latest incidents in the constant tug of war over the role of women in Iranian society. Ever since the 1979 revolution, it has pitted a traditional patriarchal Islamic system bent on imposing control and restrictions on women – such as one-sided divorce laws and the mandatory wearing of a hijab head covering – against increasingly powerful demands by women for equal rights and recognition.

Demand for accountability

“There is an emerging and fast-growing trend among different layers of the Iranian public to demand answers and accountability,” says an Iranian sociologist, a lecturer at a university in Tehran who asked to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of the issues.

The lenient court ruling in Romina’s case was widely denounced as a case study in women’s inequality and the diminished value of girls. By contrast, a woman was recently sentenced to 15 years in prison for removing her headscarf in public.

“Romina’s father picked up the sickle in full consciousness and beheaded his teenage daughter, because he was aware of the anti-women laws of this country,” fumed female journalist Niloufar Hamedi on Twitter. The father had checked with a lawyer before the murder, to be sure he would avoid the death penalty.

In the case of the math textbook, parents saw a government ploy to literally render girls invisible. They forced the education minister to apologize and launched a campaign to put new covers on the books that often include an image of the late Iranian mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani, who in 2014 became the only woman ever to win the prestigious Fields Medal, the math equivalent of the Nobel Prize.

“The wrath against the [honor killing] verdict has not been exclusive to elites, intellectuals, and women’s rights activists,” says the university sociology lecturer. “It’s been more far-reaching and has been expressed even by conservative-minded people.”

Popular anger over the gruesome murder in May of Romina, a schoolgirl who ran away from home with her older boyfriend, led the Iranian parliament to approve measures criminalizing child abuse and neglect, now called “Romina’s law,” that had been stalled for 11 years.

Another law that would criminalize sexual and physical abuse of women, first written 10 years ago, is also moving forward, albeit slowly.

Parents get book recovered

The textbook cover change has prompted many parents to seek to hide the offending image. When the father of a third grader visited a stationery shop in Tehran recently, the owner offered him three different images of Ms. Mirzakhani – the math medal winner who taught at Stanford University.

“I have had eight customers today with different photos of Maryam, asking me to print them on the cover. Who are these sick people [officials behind the removal]?” he wondered. “They can’t even tolerate pictures of two little girls in hijab?”

In mid-September, the uproar prompted the minister of education, Mohsen Haji Mirzaee, to issue a formal apology, saying there was “tastelessness behind such a decision.”

He also praised Iran’s support for female education: “The old-time discrimination that characterized women’s access to education has been entirely abolished,” he said. “Today, no girl is deprived of education in any spot in this country.”

Achievement and hurdles

Indeed, Iran is renowned for the most widely and highly educated female population in the region. Women fill 60% of the country’s university places. Despite challenges, Iranian women from Iran have been ministers, lawmakers, professors, lawyers, firefighters, and even an astronaut and Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

But the controversy has exposed again how Iranian textbooks are slanted toward masculine names and images, with one former official recently putting the figure at 70% in favor of boys.

Research into the “role and status of women” in Persian textbooks by the state-funded Center for Cultural Studies and Research in Humanities found in 2007 that only 16% of 3,029 names used were female, only 37 women were among the 782 prominent figures mentioned in lessons, and only one woman was listed among 122 notable personalities.

Agreeing that the cover “should not have been changed,” the deputy minister of education whose bureau is responsible for the math book, Hassan Maleki, demands that critics “should be fair.”

“Why don’t they see the cover on the science book for the same grade?” he asks. “The kids on that book are all girls. This indicates that there is no negative approach toward girls,” he argues.

The covers of most school textbooks in Iran show either boys or girls, but not both. This seeks “to institutionalize gender segregation among children and to indirectly teach them the very concept from such very early stages,” worries the Tehran sociologist.

For her part, the cover designer, Nasim Bahary, says she was surprised by the Education Ministry’s move, because she thought she had already complied with “multiple censorship orders” imposed in 2013 that led to the previous cover design showing both girls and boys.

But it was no surprise to Ebrahim Asgharzadeh, one of the student leaders of the 1979 U.S. Embassy seizure in Tehran, who today is a reformist politician.

“The policy of elimination [of women] and gender segregation has hit rock bottom,” he said in an Instagram post. He urged his daughter to “paste the photo of Mirzakhani on the cover of the book and take pride in being a girl.”

An Iranian researcher contributed to this report.

More nations ending soccer’s gender wage gap: ‘This could change things’

For years, the U.S. women’s soccer team has accused its federation of gender discrimination. Meanwhile, a handful of other countries’ leagues have been making waves, vowing to pay male and female players the same.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Whitney Eulich Special correspondent

Brazil’s women’s soccer team is a powerhouse, routinely ranked in the top 10 around the world. So it might come as a surprise that for decades, until 1981, Brazilian women weren’t even allowed to play.

Though such explicit sexism has receded, the business of soccer still treats men and women differently, female players say in many countries – especially when it comes to pay. Yet a small but growing cohort of countries is offering their women’s national teams as much as the men’s, which many athletes and commentators view as a major symbolic victory.

The newest members of that club – which includes Australia, New Zealand, Norway, and England – are Brazil and Sierra Leone, which both announced they had equalized pay earlier this month.

Rashidatu Kamara, who plays for Sierra Leone’s national team, is using her first paycheck since pay was equalized to finish building her parents’ house, and pay school fees for her younger siblings.

“Women in Sierra Leone often stop playing football young because they don’t see a future there,” she says. “This could change things for the generation behind us.”

More nations ending soccer’s gender wage gap: ‘This could change things’

When she was playing soccer as a child, Rashidatu Kamara never had reason to believe she couldn’t be one of the boys.

From the time she was 8 years old, they welcomed her into pickup games in their neighborhood cemetery in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Soon, she was so good that her friends would nearly come to blows about whose side she was going to play for that day.

“They never gave me reason to doubt that a girl could play,” she says.

That came later, when Ms. Kamara was called up to her national team. The first time she represented her country in a tournament abroad, she made $300, a princely sum to the child of a fisherman from a poor neighborhood. But it paled in comparison with the $2,000 the men made each time they put on their green, white, and blue uniforms for an international match.

So when Sierra Leone’s sports ministry announced earlier this month that it was equalizing payment for its men’s and women’s national teams, players like Ms. Kamara greeted the announcement with no small measure of pride.

“Women in Sierra Leone often stop playing football young because they don’t see a future there,” she says. “This could change things for the generation behind us.”

Sierra Leone’s announcement comes on the heels of a similar one by Brazil’s soccer federation in early September. The two countries join a small but growing cohort of countries, including Australia, New Zealand, Norway, and England, to offer their women’s national teams as much as the men for the same work.

In the soccer world, where equality for the women’s game is a bitter and very much ongoing fight, many view the policies as major symbolic victories.

“If we want the women’s game to improve, we have to sow before we can reap – and that means making pay equal” before popularity can be equal, says Usher Komugisha, a Ugandan journalist covering African women’s soccer. “These women stand on the field wearing the flag of their countries just like the men do – there’s no reason not to treat those experiences with equal value.”

Once banned from playing

Equal pay for the Sierra Leonean and Brazilian teams has special resonance in Africa and Latin America, where women’s soccer has been particularly neglected. In one of the world’s greatest soccer powerhouses, Brazil, for instance, women were formally banned from playing, even recreationally, from the 1940s until 1981. Such violent sports as soccer, the law stated, were “not suitable for the female body.” (Similar bans were in place in several European countries until the early 1970s.)

And when the coronavirus pandemic hit Africa in 2020, the Confederation of African Football announced that it was canceling the women’s continental championship. The men’s tournament, meanwhile, was simply postponed.

It sets an important example when a national football federation puts equality before public opinion at home, says Marília Ruiz, a Brazilian sports commentator and columnist.

“Brazilian society still treats soccer as a male sport,” she says.

At the same time, she and others note that equal pay for national teams is only a small piece of the puzzle in making soccer less sexist. National team pay policies can be a “PR move” to make a country’s football federation look good while deflecting from more systemic problems, says Ms. Komugisha, who advocates for pay equity in women’s soccer in Africa.

Brazil, for example – whose national team is routinely ranked in the world’s top 10 – doesn’t have a domestic professional league. The country’s best players often leave the country to play for European and American leagues, and in 2017, several members of the national squad quit at once, saying they were “exhausted from years of disrespect and lack of support” from the country’s soccer federation.

Fernanda Stulpen played goalkeeper for Brazil’s national team in 2006. She says she never could have imagined a pledge for equalized pay when she was on the team.

“The fact that we received anything at that time already helped so much, since the majority [of women players in Brazil] got nothing,” Ms. Stulpen says. Her biggest hope is that the change in pay can boost the value placed on women’s soccer.

Brazil is also home to arguably the best female soccer player of all time: six-time FIFA player of the year Marta Vieira da Silva, who is also the World Cup’s leading goal scorer – man or woman. Yet Brazilians often refer to her as “Pelé in a skirt,” setting her up as only an echo of the country’s most famous male player.

“The [payments] are equal now, but the conditions to get to them are not,” Ms. Ruiz says.

FIFA prize money

One of the greatest stumbling blocks to truly equal pay is FIFA, soccer’s global governing body, which doles out prize money for global tournaments like the World Cup. In 2018, the federation set aside $400 million in prize money for teams participating in the men’s World Cup, including $38 million that went directly to France, the winner. By contrast, FIFA offered $30 million in prize money for the Women’s World Cup the following year. The champions, the United States, received $4 million, about 10% of the men’s takings. FIFA has argued that the discrepancy results from the difference in revenue.

“I think sometimes FIFA can be a device for [national] federations to explain progress or lack thereof,” says Brenda Elsey, professor of history at Hofstra University in New York and co-host of the sports and feminism podcast “Burn It All Down.” FIFA’s lack of support for the women’s game, she says, makes it easy for member countries to follow suit.

Part of the problem, many say, is that soccer’s powerful governing bodies remain largely a boys’ club. The president of FIFA has never been a woman, and the organization named its first female secretary-general, Senegalese diplomat Fatma Samoura, only four years ago. Meanwhile, only three of FIFA’s 211 member states currently have a national soccer federation run by a woman. Two of them are the United States and Turks and Caicos Islands.

The third is Sierra Leone.

The Sierra Leonean association’s president, Isha Johansen, “has been championing women and girls’ football for a long time,” says Ms. Komugisha, the Ugandan commentator and activist.

So it wasn’t a surprise, Ms. Komugisha says, to see Sierra Leone step out in front of the field in terms of equalizing pay.

For Ms. Kamara, the team’s first payment of $2,000 was more than anything she’d ever seen. She’s using it, she says, to finish building her parents’ house and to pay the school fees of her younger siblings.

“I tell women to be successful in this game, you have to eat, sleep, breathe football. It is about your passion. The money isn’t everything,” she says.

“But the money is helpful too.”

Points of Progress

How a reforestation project smashed its goal

From a new way to protect wildlife against trafficking in the Philippines to Afghan moms no longer being erased, start your week with stories of progress happening around the world.

How a reforestation project smashed its goal

World

Researchers say the world’s largest reforestation project – the 2011 Bonn Challenge – has beaten its 2020 target. Launched nearly a decade ago by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Germany, the challenge aims to have 371 million acres of degraded forest under restoration by the end of the year. According to a recent IUCN report, 61 nations plus states in Brazil, Mexico, and Pakistan and some environmental groups have committed to restoring roughly 519 million acres. Experts say a key element of the Bonn Challenge’s success is that the drive was about more than planting trees: Countries have used their pledges to address national priorities such as food security and job creation. On a national level, reforestation campaigns can be effective economic stimulus measures. Preliminary analysis suggests that every dollar invested in restoring forests generates $9 of economic benefits. (Thomson Reuters Foundation)

1. United States

A record number of Black female tennis players represented the United States in the U.S. Open. Just 10 years ago, Venus Williams was the only African American in the U.S. Open women’s singles draw. Now, 12 Black players were in the recent women’s singles tournament, including Venus and Serena Williams plus several up-and-coming players. This figure does not include Naomi Osaka, who plays for Japan but grew up in the U.S. watching the Williams sisters.

This is a major shift for the historically white-dominated sport. The United States Tennis Association says African American girls currently make up roughly 15% of training camp attendees, on average, at various playing levels. According to U.S. census estimates, Black people make up 13% of the U.S. population. “It all starts with Venus and Serena,” said Martin Blackman, general manager of player development at the USTA. “That attracted thousands of girls into the sport, not just African American but all backgrounds and races.” (The New York Times, Business Insider)

2. United States

After sitting vacant for nearly a decade, a former inn in Branson, Missouri, has been converted into affordable housing, potentially providing a model to address housing shortages across the country. Los Angeles-based development company Repvblik combined hotel rooms to create studio and single-bedroom apartments that rent for as little as $495. Unlike typical developments, the Branson project didn’t rely on federal funding. Repvblik founder Richard Rubin says there’s room for many other developers to start repurposing large, abandoned commercial spaces into affordable housing units. These kinds of adaptive reuse plans are often subject to zoning challenges, but can feature environmental and cost benefits because they require fewer new building materials. Investors are starting to see the value in the new model, with the company working on about 10 similar projects. “We hope to create about 20,000 apartments within the next five years,” said Mr. Rubin. (Fast Company, Forbes)

3. Afghanistan

Mothers’ names will now be printed on national identification cards in Afghanistan, a significant step in dismantling deep-rooted taboos around women’s role in public life. Despite great strides in women’s leadership since the toppling of the Taliban, activists say Afghans still face intense misogyny masquerading as religiosity. Until now, women weren’t included in the country’s definition of identity; IDs only included the person’s first and last names, father’s name, and date of birth. Because of these norms, widows often struggle to do business or assert themselves as legal guardians of their children without a man present.

The proposal to amend the census law comes after years of campaigning by activists, and more recently a social media campaign asking #WhereIsMyName? The Afghan Cabinet’s legal committee approved the change, and officials expect parliament and the president to sign off soon. Laleh Osmany, a campaign supporter, celebrated the government announcement, saying the amendment “is about restoring the most basic and natural right of women that they are denied.” (The New York Times)

4. Qatar

Labor reforms in Qatar are ending the widely criticized kafala – or sponsorship – system, in which an employee needs permission from his or her boss to switch jobs. For years, rights groups say this system led to exploitation and even forced labor among the country’s migrant workforce of roughly 2 million. A new law, first announced last October and passed in late August, allows workers to change jobs more freely. Combined with the January abolition of an exit permit requirement for foreign workers to leave the country, the reforms mark “the beginning of a new era for the Qatari labour market,” according to the United Nations’ International Labor Organization. Workers and advocates welcomed the reforms, but emphasized the need for rigorous and consistent enforcement. (The Guardian)

5. Philippines

The Philippines is launching a new mobile app to combat wildlife trafficking, an illegal trade estimated at $1 billion a year that threatens the country’s biodiversity. Currently, Filipinos can report suspected wildlife trafficking incidents through a Department of Environment and Natural Resources hotline, but a lack of cellphone reception or species knowledge can pose barriers to reporting. The WildAlert app is designed to empower anyone, in any part of the country, to fight the illegal wildlife trade. Its offline mode helps overcome patchy internet reception by automatically recording the time and location of an incident and sending that data to the nearest DENR office once the user has a signal. The georeference feature and centralized data collection system will also help law enforcement monitor the trafficking crisis in real time. As wildlife enforcement officers and the public wait for WildAlert’s full rollout, they can access the app’s wildlife library of 480 species – including conservation status and common names in local dialects – on the website WildAlert.ph. (Mongabay)

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A war in the Caucasus as a window on what brings peace

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In the latest ranking of nations based on their “peacefulness,” democratic Armenia showed the most progress. Since Sunday, however, it has been embroiled in a dangerous war over disputed territory with its neighbor Azerbaijan. That country, with an authoritarian leader, ranks lower in the peace rankings.

Just who started this war is not yet clear. Yet the answer would be telling. Is democracy a deterrent to war? And do dictators initiate external conflicts more often to retain power? Perhaps the way this war ends will shed light on which of the two governments needed to fight a foreign enemy. Among some experts, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev has the greater incentive to rally his people around the flag. In contrast, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan is known for his role as a no-violence activist who led the protests that brought down an authoritarian government.

The current war may end with outside mediation by big powers. Yet the real end to the underlying conflict will come with a full blossoming of democracy in both countries. In recent centuries, progress against violence has been linked to a rise in freedom and equality.

A war in the Caucasus as a window on what brings peace

In the latest ranking of nations based on their “peacefulness,” the small landlocked nation of Armenia in the Caucasus region showed the most progress. It shot up 15 places on the Global Peace Index to 99. This was largely due to a nonviolent revolution in 2018 that restored much of its democracy. Since Sunday, however, Armenia has been embroiled in a dangerous war over disputed territory with its neighbor Azerbaijan. That country, with an authoritarian leader, ranks only 120 on the index.

Just who started this war is not yet clear. Yet the answer would be telling. Is democracy a deterrent to war? And do dictators initiate external conflicts more often to retain power? Perhaps the way this war ends will shed light on which of the two governments needed to fight a foreign enemy.

Among some experts, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev has the greater incentive to rally his people around the flag. The pandemic has greatly reduced revenue from exports of oil and gas. Social grievances, especially over police brutality, are piling up. During a short military skirmish with Armenia in July, a pro-government demonstration quickly turned against the regime.

Mr. Aliyev has reason to worry over his popularity. He also has turned to Turkey for military help, fired an official in charge of peace talks with Armenia, and spent millions on advanced weapons.

In contrast, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan is known for his role as a no-violence activist who led the protests that brought down an authoritarian government. His view of security is less in building up the military and more in fighting corruption, improving rule of law, and encouraging self-governance. While he faces tough political opponents from the previous regime, he remains popular.

Since the 1990s, the two countries have struggled over Nagorno-Karabakh, a majority-ethnic Armenian enclave under Azerbaijan’s jurisdiction. As Armenia has moved toward full democracy, the conflict has become a test of whether that form of government better allows grievances to be addressed and reduces nationalist aggression as a way to distract from domestic problems.

In the past decade, during a time of global decline in democracy, the vast majority of the increase in armed conflict has taken place in authoritarian regimes, according to the Institute for Economics & Peace. In addition, authoritarian regimes spent 3.7% of gross national product on military expenditures in 2019. Full democracies spent only 1.4% of GDP.

The current Armenia-Azerbaijan war may end with outside mediation by big powers. Yet the real end to the underlying conflict will come with a full blossoming of democracy in both countries. In recent centuries, progress against violence has been linked to a rise in freedom and equality.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Have you thought about holiness lately?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

More than an abstract, impractical concept, the idea that God has made us holy opens the door to more peace – even during stressful times.

Have you thought about holiness lately?

I think it’s safe to say that the subject of holiness doesn’t come up much in our daily conversations. Too abstract and impractical for the problems of today’s world, some might say.

Here’s another perspective: Holiness is well worth thinking about.

Maybe you hold in your heart even one memory of a peace that encircled you during a tough time. Somehow it outshined the problem, and you felt confident you’d find an answer.

This is what I call a “holy moment.” These moments happen more naturally as we come to understand, through prayer, more of the constancy and universal availability of God’s powerful, loving presence. Then the way opens for solutions.

God gave to Moses this message to share with the Israelites he was leading out of captivity: “You shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy” (Leviticus 19:2, New King James Version). This promise defines for all time the divine nature of God, which includes within its infinitude pure goodness and nothing else. It points to the true spiritual heritage of all of us as the holy and dearly loved children of our loving Parent.

One definition of the word “holy” is set apart for a sacred purpose. Prayer that helps us see our pure unity with God – our holiness – empowers us to fulfill our God-given purpose: to glorify God by expressing qualities such as goodness and serenity.

A small incident that highlighted our ability to feel this serenity in a stressful circumstance occurred at a time when my husband and I were traveling by plane for a fairly tight schedule of work engagements.

We had left for the airport by taxi in plenty of time, but soon the traffic was hardly moving. If we missed the flight, it would mean not only more expense but also a disruption of planned events, which were intended to be of service to others.

As we have consistently done in our lives when obstacles arise, we began to pray. In the Bible, the prophet Isaiah speaks of the desert that will blossom with flowers, and the barren land that will be filled with springs of water. As “The Voice” translation states: “The road to this happy renovation will be clearly signed. People will declare the way itself to be holy – the route, ‘sacred.’... There’ll be no lions lying in wait, no predators or dangers in sight” (see Isaiah 35).

I have consistently looked to Jesus as the highest example of the holy manifestation of God’s love. The Christ, the understanding of divine Truth through which Jesus renewed and healed, enables us to experience God’s care today, too.

So in prayer, I mentally affirmed that God is all good and the only legitimate cause of existence. Although it sure seemed otherwise right then, all of us caught in this gridlock were, in spiritual reality, moving in harmony with the love of God and therefore with each other. How freeing it was to know this was the actual truth right then about the spiritual identity of everyone, everywhere.

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, studied the deep and inspired meaning of the Bible. Speaking directly to what it means for our consciousness to be holy, she wrote in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “To discern the rhythm of Spirit and to be holy, thought must be purely spiritual” (p. 510).

I saw that because this inspiration was coming to me from God, Spirit itself, nothing could oppose or obstruct the divine power behind it. I was able to confidently dismiss feelings of anxiety, pressure, and limitation as having no source in God, good. This brought holy moments – moments of trust and calm – in the midst of the blocked traffic.

Finally, about 10 minutes before the flight was to take off, we arrived at the airline counter. There we learned that the traffic situation had affected the whole city, and the considerate decision had been made to delay the flight. We were able to board and fulfill our commitments for the trip. How grateful I was for this, but what has especially stayed with me is the uninterrupted joy of feeling tangibly that God, Love, gently cares for all.

Not all my moments and days feel holy. But I know it is possible to have more that do. Because divine Love is never absent – even for a moment – each of us has the capacity to experience Love’s holy blessings.

A message of love

Battling more blazes

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow when we’ll have a deep-dive look at Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden from Washington Bureau Chief Linda Feldmann.