- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Wedding rings, ancient marbles, and the power of giving back

After a week brimming with examples of giving thanks at a difficult moment, we’re also getting lessons in the power of giving back – literally and figuratively – as we head deeper into the holiday season.

Early this month, members of Open Arms Italy, which rescues migrants in the Mediterranean, found a backpack floating in the water. In it were two wedding rings engraved with two names. Wreckage nearby boded poorly for finding the owners, but the rescuers were undeterred, The New York Times reported. La Repubblica newspaper picked up the story, asking, “Who are Ahmed and Doudou?” And in a moment of light, a young couple surfaced in a reception center in Sicily, having been rescued by fishermen after a harrowing capsizing off Libya. “We had lost everything, and now the few things we had set out with have been found,” they said.

Then there were the workers at the National Roman Museum who opened a package sent from the United States and found an ancient marble fragment. Apparently it was filched from a cultural site in 2017, the Guardian reported. Equally inspiring was what accompanied it: the sender’s abject apology.

“The year 2020, decimated by the COVID pandemic, has made people reflect, as well as moved the conscience,” museum director Stéphane Verger said. “The fact is that three years after the theft, she returned it – it’s a very important symbolic gesture.” The letter, he added, “was quite moving.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

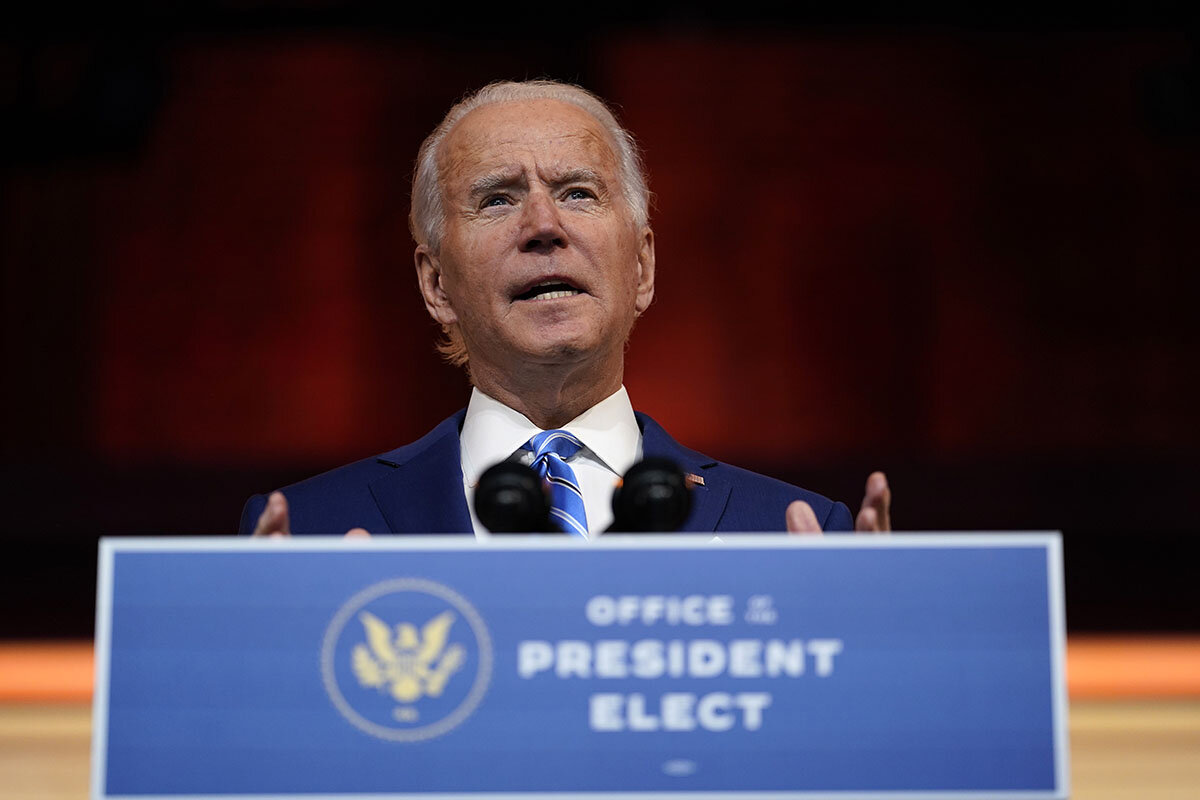

Trump administration seeks to tie Biden’s hands. Will it work?

Presidential transitions are never easy. But the flurry of “midnight regulations” being set in motion by the Trump administration adds another disruptive dimension to a handover already marked by tumult.

American history is replete with messy presidential transitions, including the contested election of 2000 – when the W’s from some office computers were famously removed as George W. Bush prepared to take over.

The current changeover, however, stands to be among the most consequential in modern history.

From a raft of end-of-term regulations and executive orders, to the Treasury’s move to “claw back” hundreds of billions of dollars in unspent emergency-lending funds, to a host of foreign-policy actions, President Donald Trump and his team have been busy in an apparent effort to tie the incoming Biden administration’s hands.

Even if everything were going smoothly, and the outgoing and incoming administrations were working hand in glove, this transition would be difficult, says Rudy Mehrbani, a senior adviser at the nonpartisan Democracy Fund Voice.

“But when you add the crises we’re facing as a nation, combined with the shorter transition period, and now combined with Trump’s intentional efforts to obstruct the new administration, the potential toll on human health and lives could be disastrous though impossible to ever quantify,” says Mr. Mehrbani, a former member of the White House Transition Coordinating Council under President Barack Obama.

Trump administration seeks to tie Biden’s hands. Will it work?

Drama has long been essential to President Donald Trump’s brand, and the post-2020 election period is delivering in spades.

President Trump’s legal challenges to the election results in multiple states are Exhibit A. But as that fight reaches its denouement, after repeated defeats in court, a more concretely impactful kind of drama is playing out: apparent efforts to tie an incoming Biden administration’s hands on both domestic and foreign policy.

From a raft of end-of-term regulations and executive orders, to the Treasury’s move to “claw back” hundreds of billions of dollars in unspent emergency-lending funds, to a host of foreign-policy actions that could limit President-elect Joe Biden’s room for maneuver, Mr. Trump and his team have been busy.

American history is replete with messy presidential transitions, including the contested election of 2000 – when the W’s from some office computers were famously removed as George W. Bush prepared to take over, symbolic of the deep animosity that accompanied the arrival of the new president.

But the conflicts marking the current changeover stand to be among the most consequential.

“In modern memory, from what I’ve seen, this is going to be one of the most challenging transitions in the country’s history,” says Rudy Mehrbani, a senior adviser at the nonpartisan Democracy Fund Voice.

Even if everything were going smoothly and the outgoing and incoming administrations were working hand in glove, this transition would be difficult, he adds.

“But when you add the crises we’re facing as a nation, combined with the shorter transition period, and now combined with Trump’s intentional efforts to obstruct the new administration, the potential toll on human health and lives could be disastrous though impossible to ever quantify,” says Mr. Mehrbani, a former member of the White House Transition Coordinating Council under President Barack Obama.

In the domestic sphere, examples of controversial end-of-term moves by the White House and federal agencies include:

- Dozens of government regulations, with sped-up timelines for approval, that affect food and worker safety, oil drilling in national parks, migrant workers, food stamps, endangered species, transgender people, refugees, and federal executions, among other issues.

- Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin’s move to put $455 billion in unspent COVID-19 stimulus relief money back in the Treasury’s general fund. Janet Yellen, the incoming secretary, if confirmed, would have to get permission from Congress to access the funds for that purpose. Secretary Mnuchin denies he is trying to hinder the incoming Biden administration.

- A major change to the federal civil service – called the biggest in generations – that would reclassify tens of thousands of career employees into political appointees, removing job protections. Such a move would make it easier, for example, for the current president to fire Anthony Fauci, the nation’s leading epidemiologist, with whom he has clashed.

Already, the Oct. 21 executive order signed by Mr. Trump is reportedly accelerating at a key agency, the Office of Management and Budget. Reclassifying employees at other agencies is also being “fast-tracked” ahead of the Jan. 19 deadline into the new job category, known as “Schedule F.”

On his first day in office, Mr. Biden is expected to sign dozens of executive orders reversing many of Mr. Trump’s – including his orders quitting the Paris climate accord and the World Health Organization – but unwinding the Schedule F move won’t be easy. Employees who have been fired can’t necessarily be instantly rehired, nor can those hired under the new job category be immediately dismissed.

Mr. Biden is also expected to try to make use of the Congressional Review Act (CRA), which allows for the overturning of regulations within a certain period. Though if Democrats don’t win the two U.S. Senate seats up for grabs in a Jan. 5 runoff election in Georgia, Republicans will still control the Senate, and Mr. Biden’s ability to use the CRA will be limited. Mr. Trump, by contrast, was able to reverse 14 Obama-era rules in his first four months in office, as the Republicans then controlled both houses of Congress.

Today, the flurry of so-called midnight regulations being set in motion by the Trump administration adds yet another head-spinning dimension to a transition that is already marked by tumult. One factor may be that Mr. Trump appeared unprepared to lose the Nov. 3 election.

“The rules issued between now and inauguration may be more haphazard than in previous administrations, in part because President Trump is generally less disciplined than his predecessors,” writes Susan Dudley, director of the George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center, in an email.

What’s more, because the last three administrations knew their time in office would end after a second term, they also had time to focus on finishing their highest-priority actions, adds Ms. Dudley, former head of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs during the second Bush administration.

Since Election Day, Mr. Trump has also taken numerous foreign-policy steps whose goals or implementation don’t necessarily mesh with those of the incoming Biden team:

- Announced troop level cuts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

- The formal exit of the United States from the so-called Open Skies Treaty, which allows Russia and the West to engage in reconnaissance flights over each other’s territories. Rejoining the treaty wouldn’t be simple. The U.S. has moved to get rid of the special planes it used to carry out surveillance.

- Arms sales to the United Arab Emirates worth $23 billion, which could alter the balance of power in the Middle East.

- Added sanctions on Iran that would make it harder for the United States to rejoin the Iran nuclear deal.

Despite all the postelection drama, which began when Mr. Trump decided to contest the results and refused to allow the formal transition to begin, the process now appears on track. On Nov. 23, nearly three weeks after the election, the Trump administration “ascertained” Mr. Biden as the apparent winner, allowing for the release of federal funds and sharing of information with the incoming Biden team – including on the pandemic and plans for distribution of vaccines.

Experts on presidential transitions say the three-week delay was unfortunate but not as damaging as the one in 2000, which lasted six weeks.

“Biden is the most experienced person ever to become president, and his transition team is the deepest, most experienced, and best organized transition team ever, and so that mitigates the impact of the delay,” says David Marchick, director of the Center for Presidential Transition at the Partnership for Public Service.

Mr. Marchick says the transition so far has gone “very well.” His organization works with the three key stakeholders: the Trump White House, the agencies responsible for transition planning, and the Biden team.

Experts also credit the Trump administration for being ready – before the election – to carry out a transition, including preparation of briefing books. But once the election had taken place, followed by numerous efforts to overturn the results in key states, partisan hackles were raised – hardly a surprise in this era of anger and division.

And so the transition, too, fell prey to those sentiments.

“I’m not surprised this transition is angry and bitter, and that the outgoing administration will try to leave political hand grenades everywhere they can,” says Jeffrey Engel, founding director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. “But it’s hardly the first or even the 10,000th example of the norms of civility breaking down in our politics.”

On Russia’s flank, a small war heralds big changes

The dramatic outcome of the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan was a troubling victory for the use of force – and left international diplomacy licking its wounds. This story explains how that happened.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The recent six-week war between Armenia and Azerbaijan offers a stark lesson in the costs of diplomatic failure: An unresolved territorial dispute suddenly erupted in violence that took thousands of lives and left a vastly changed landscape in its wake.

The two neighbors have long been embroiled in a territorial dispute. Armenia won a war over the Nagorno-Karabakh region in the 1990s, and the international community then rallied round a diplomatic settlement. But nobody pushed the peace plan very hard, not even the United States, France, and Russia, who were tasked with mediating.

This time – helped by Turkey – Azerbaijan won the war. In the North Caucasus, the tables are turned. And more broadly, Turkey has extended its reach, forcing Moscow to share its regional influence.

Now that the fighting has stopped, “diplomacy will be given a fresh opportunity to work something out,” says Russian analyst Sergei Markedonov. But this time the diplomats will come from Ankara and Moscow, not from Washington or Paris.

On Russia’s flank, a small war heralds big changes

This autumn’s intense six-week war between Armenia and Azerbaijan offers a stark lesson in the costs of diplomatic failure: An unresolved territorial dispute suddenly erupted in violence that took thousands of lives and left a vastly changed landscape in its wake.

Azerbaijan won the war with arms and advice from Turkey, dramatically reversing Armenia’s decisive victory a quarter century ago that had been frozen in place since 1994.

The nub of the conflict is the Armenian-populated exclave of Nagorno-Karabakh, a Soviet-era autonomous region inside Azerbaijan that declared independence in 1988 as the USSR began to crumble. In the long and bloody war that ensued, Armenian forces not only secured the region, they occupied a huge swath of additional territory and expelled around 800,000 ethnic Azeris from it.

The new armistice, which Russia imposed last month, restores all of those illegally seized lands to Azerbaijan and inserts 2,000 Russian peacekeeping troops into the area to enforce the deal. Turkey is also expected to play a role. But the accord leaves the original problem, the status of Nagorno-Karabakh – now under Russian protection – to be settled by future negotiations.

This dramatic outcome has triggered mass jubilation in Azerbaijan, plunged Armenia into a storm of national anguish, and left international diplomacy licking its wounds. The cease-fire lines brokered by Moscow almost exactly follow the diplomatic settlement that the international community had advocated for almost 30 years, but they were achieved by force of arms.

The Minsk Group, comprising the United States, France, and Russia, which had been charged with resolving the conflict, proved irrelevant as the crisis climaxed; it was two regional powers, Russia and Turkey, that brought the warring parties to heel.

Now, says Sergei Markedonov, an expert with the Institute for International Studies, a think tank attached to the official MGIMO University in Moscow, “diplomacy will be given a fresh opportunity to work something out.”

But “it is not going to be easy,” he adds, because “that small territory is seen as a key element in the national identities of both Armenia and Azerbaijan.”

Some of the 100,000 Armenians who fled Nagorno-Karabakh during the war are starting to trickle back to their homes through the Lachin Corridor, a slender land link between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh that is now secured by Russian forces. Many other residents had burned their houses as they left, rather than hand them over to the advancing Azeris.

Those who do return are facing a very uncertain future, and Azeri ideas of a permanent settlement appear to have hardened. Nagorno-Karabakh’s 28-year-long dream of independence is clearly shattered, and even a return to something like Soviet-era autonomy, which gave the Armenian population a great deal of linguistic, cultural, and political leeway, now seems off the table.

“Azerbaijan was ready to grant autonomy to the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh if Armenia had been ready to accept a peaceful resolution of the conflict,” says Farid Shafiyev, president of the independent Center of Analysis of International Relations in the Azeri capital, Baku.

However, since Armenia never accepted the diplomatic solutions offered, Azerbaijan was compelled to fight for the land “at very great cost in lives of our soldiers,” he says.

“Now conditions have changed. Armenians who want to live in Azerbaijan in future may enjoy the same privileges as other minorities, such as Kurds, Jews, and Russians, whose language, religion, and other rights are protected by law,” Mr. Shafiyev predicts.

The victorious war has made a public hero of Azerbaijan’s hereditary despot, Ilham Aliyev.

Some people are concerned that the Russian peacekeeping force on Azeri soil, due to stay five years, “might turn into a permanent Russian military presence,” says Ilgar Velizade, an independent political analyst in Baku.

“But this peace deal looks workable. It registers the geopolitical reality in our region, and reflects the will of the two leading powers, Russia and Turkey. It provides a basis for these two to cooperate here in the long term.”

In Armenia, the sense of shock and denial has been magnified by a national historical memory that associates the fate of Nagorno-Karabakh with the genocide committed against Armenians by the Ottoman Turks just over a century ago. (One reason for Armenia’s reluctance to negotiate over the seven occupied Azeri districts around Karabakh has been its lack of trust in Azerbaijan, a Turkic-speaking nation closely aligned with Turkey.)

“I understand the feelings of many Armenians and the trauma they have suffered” from their unexpectedly swift defeat, says Mr. Markedonov. “But they should realize that without Russia stepping in and imposing this cease-fire, the Armenian defeat might have been much worse.”

And the angry crowds and opposition leaders who have been demanding that Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan resign for conceding defeat are themselves partly to blame, argues Gayane Ayvazyan, a historian and peace activist in the Armenian capital, Yerevan.

“These people are the same ex-leadership who insisted on never negotiating, never giving an inch,” she says. “They fed us incessant militarization and war propaganda. Now they want Pashinyan to leave because he had no choice but to accept a defeat that they bear great responsibility for.”

It’s a pity, she adds, that Armenia’s pro-democracy movement two years ago, which brought Mr. Pashinyan to power, failed to recognize that resolving the frozen conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh was critical to building a healthy, lasting democracy.

For Russia, even though it may now have to share its regional influence with Turkey, the armistice is a satisfying outcome that has solidified its role and strengthened its grip on Armenia.

“As a result of this, Armenia is under Russian patronage much more than before,” says Fyodor Lukyanov, editor of Russia in Global Affairs, a Moscow-based foreign policy journal. “That’s a very strategic neighborhood so, even after five years of peacekeeping, Russia may well decide a permanent presence is called for.”

A deeper look

In California, rethinking who ‘owns’ wildfire

After a devastating fire season in the American West, differences have flared over how to reform fire and land management. But many agree on one key point: that everyone needs to be part of the solution.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 11 Min. )

Even before this year’s record wildfires in California, Lenya Quinn-Davidson was pushing for a new approach to addressing fire risks. A fire area adviser with the University of California system, she has traversed the state since 2018 to promote the idea that controlled fires can help curb uncontrolled ones.

With her help, private landowners and others are learning how to use prescribed fires to thin the accumulated vegetation in woodlands.

But the challenge is formidable. Climate change has increased the danger posed by wildfires, even as a century of suppression by fire agencies has created the conditions for 4.2 million acres in the state to burn this year, more than twice the state’s prior modern-era high.

In California, the state and the U.S. Forest Service have agreed to treat 1 million acres of wildlands a year by 2025 through prescribed burning or other means of thinning. But fire agency spending remains heavily skewed toward suppression.

“We’re all affected by wildfires, so let’s try to help ourselves and each other,” says Norm Brown, a former California fire-response official who now promotes controlled burns. “It’s about cooperation.”

In California, rethinking who ‘owns’ wildfire

Wildfire has illuminated Norm Brown’s life. In 1983, he joined California’s primary firefighting agency, known as Cal Fire, and during the next three decades, he worked thousands of fires, protecting lives, homes, and land. He retired as a deputy chief in 2017, and since then he has stayed close to the flames – by choice and by chance.

As a member of the Mendocino County Prescribed Burn Association, a volunteer coalition of community members and retired firefighters, he oversees controlled burns on private property to reduce the excess vegetation that feeds fires. As a resident of Willits, a small town northwest of Sacramento, Mr. Brown watched this summer and fall as the largest wildfire in state history ravaged nearby Mendocino National Forest, burning more than 1 million acres.

A blitz of dry-lightning strikes in August sparked that blaze and hundreds of others in Northern California. The fires forced tens of thousands of residents from their homes, and when more infernos ignited in Oregon and Washington in September, the entire West appeared aflame.

The smoky skies crystallized the limits of the aggressive wildfire suppression policy that prevails among federal and state firefighting agencies, including the U.S. Forest Service and Cal Fire. The century-old strategy of dousing most fires as quickly as possible – born of good intentions to save people and property – has wrought forests, grasslands, and shrublands teeming with overgrowth primed to burn as the climate turns warmer and drier.

For Mr. Brown, who devoted his career to snuffing out wildfires, the dystopian spectacle of 2020 has offered nature’s strongest warning yet for the West to reconsider its approach to tending natural lands. “We’ve had a lack of land management, and that’s not a problem that’s going to fix itself,” he says. “So we’re going to have to work together to figure out the answers.”

The breadth of destruction has amplified calls from fire and forestry experts for greater balance between suppression and stewardship to revive ecosystems and lower wildfire risk. The shift will require fire response agencies to collaborate with private land managers and prescribed burn associations, and will demand comparable effort by communities and individuals to adapt to the realities of living with fire.

The West has endured three decades of deepening hardship as ailing forests, climate change, and unrestrained development force a reckoning with wildfires gaining in scale and intensity. Five of the six largest wildfires in California’s history have occurred this year, and the 4.2 million acres burned – more than double the state’s modern-day record set in 2018 – have claimed 31 lives and destroyed 10,500 homes and buildings.

Malcolm North, a research ecologist with the Forest Service in Northern California, suggests that healing the land will depend on collective resolve.

“There’s a partisan divide that has crept into the wildfire discussion. One side says it’s all due to forest management, the other side says it’s all due to climate change. The truth is it’s a combination of both,” he says. “The time for pointing fingers is long past.”

A lopsided emphasis

The Forest Service embraced suppression as its guiding principle after the “Big Blowup” of 1910, when a firestorm scorched 3 million acres and several towns across the Northwest, and state agencies later adopted the ethos. Forestry scientists assert that the massive fires in recent months provide the latest evidence of a lopsided emphasis on suppression that has caused the Forest Service to fall behind on restoring 80 million acres under its care.

Naturally occurring wildfires sustain woodlands and grasslands by thinning dense tree stands and accumulated vegetation, enabling new grasses and plants to sprout and older, more fire-resistant trees to thrive. The ongoing disruption of that cycle has harmed biodiversity and contributed to California witnessing, since 2003, 14 of its 15 largest wildfires on record.

“People see a big fire and say, ‘It’s an act of God.’ That’s not the case,” says Mr. North, who teaches forest ecology at the University of California, Davis. “What we’re seeing is the result of a century of land management decisions that created all that fuel to burn.”

Researchers ascribe the bias toward suppression within fire response agencies to an entrenched culture that frames wildfire as a war that can be “won” with more personnel, equipment, aircraft, and technology. Cal Fire’s funding for suppression hit $890 million in fiscal year 2018-19, a nearly tenfold increase from eight years earlier. The Forest Service’s firefighting budget more than quadrupled during that span, reaching $2.6 billion.

Rising temperatures and falling moisture levels have stretched the West’s annual fire season by 75 days since 2000, and drought and a bark beetle epidemic have killed 150 million trees in California. As the sprawling “fire-industrial complex” struggles to subdue infernos that burn hotter and faster, funding lags for land management programs that could ease reliance on suppression over time.

The Forest Service allocated $435 million for prescribed burns on national lands in 2018, or one-sixth the amount for suppression. Cal Fire spends $80 million on fire prevention and forest health programs, less than 10% of its firefighting costs.

The comparatively modest funding delivers decidedly modest results. The federal government – owner of more than half of California’s 33 million acres of forest land – applies controlled fire on 50,000 to 60,000 acres a year statewide. Cal Fire’s prescribed burn crews treat 20,000 to 50,000 acres on public and private lands.

The figures contrast with the findings of one study that estimated the state needs to treat 20 million acres through controlled burning and vegetation thinning to reduce its wildfire threat.

Mr. Brown, the former Cal Fire deputy fire chief, explains that the duty to preserve public safety depletes resources. At the same time, unless federal and state agencies focus more on land stewardship, he foresees a future as combustible as the recent past.

“If we put money toward year-round crews to do the difficult work of fuels treatment, that would make a big difference,” he says. “We have to get more balance with our fire management.”

The need for more fire

A sense of urgency about redressing the disparity has taken root among public officials in recent months after years of mounting devastation – and decades of warnings from wildfire experts.

Three U.S. senators have proposed $600 million in funding for prescribed burning initiatives to aid wildfire prevention in the West. Another Senate bill would authorize three large-scale land management projects to restore fire-adapted forests.

In California, the state and the Forest Service have agreed to treat 1 million acres of wildlands a year by 2025 through prescribed burning, mechanical thinning, and limited logging.

A national strategy to reform wildland fire management established under President Barack Obama in 2014 nurtures similar federal-state alliances between public agencies and private land managers, including environmental groups, ranchers, timber interests, and Native American tribes. The initiative identifies wildfire and prescribed fire as essential to the resilience of forests, grasslands, and watersheds.

Land managers have blended natural and controlled fire to foster healthy ecosystems in Kings Canyon, Sequoia, and Yosemite national parks in California. Fire ecologists first performed prescribed burns in the parks a half-century ago after noticing that extinguishing wildfires upset habitat and wildlife equilibrium, and they soon returned to allowing natural fires to spread.

The “let-burn” tactic is far more fraught when a blaze sparks closer to communities, and likewise, fire officials remain wary of conducting controlled burns near populated areas. Their concerns trace to complaints about smoke from residents and potential liability, even as prescribed fires seldom escape containment.

Yet in the view of Stephen Pyne, the author of more than a dozen books on wildfire, the West’s explosive infernos illustrate the need for more fire on the landscape – let-burn and prescribed alike. He weighs the possible risks against 8 million acres incinerated across the region since August.

“We have to take advantage of wildfire the best we can and use prescribed fire when and where it makes sense,” says Mr. Pyne, a professor emeritus of environmental history at Arizona State University. “There will be fire and smoke either way. The choice is what kind of fire and smoke we want.”

The path forward for California could entail reviving cultural fire practices that existed widely in the pre-1800s, when at least 4.4 million acres burned each year before the influx of Euro-American settlers. By comparison, as a result of unrelenting suppression, wildfires burned only 250,000 acres a year from 1950 to 1999.

Flames flickered on precolonial lands from lightning strikes and intentional fires set by Native Americans. Tribes applied low-grade fire to remove grasses and scrub to grow plants for food, making baskets, and luring game, and to clear wildfire fuels around their villages.

Lightning ignited a blaze in September that swept through the Karuk Tribe’s ancestral territory near California’s northern border. The fire consumed 157,000 acres, feasting on a forest choked with grasses and brush and trees, and leaving behind ashes and anguish amid the rubble of 200 homes.

The disaster bore the sadness of centuries for Bill Tripp, a deputy director in the tribe’s Department of Natural Resources. He has absorbed repeated rejections from federal and state officials to expand cultural burns on the tribe’s land to a scale that could reduce wildfire danger. He looks upon the charred forest as a tragic argument in favor of Western tribes conducting larger burns vital to honoring their heritage and renewing the land.

“We want to do prescribed fire because our communities have had too much uncontrolled fire,” he says. “That’s what the entire West has to do right now.”

Unrealized potential

The national wildland fire strategy devised in 2014 details the importance of educating community members about the benefits of putting fire on the landscape. Lenya Quinn-Davidson has committed to that cause as director of the Northern California Prescribed Fire Council.

Two years ago, she co-founded the West’s first prescribed burn association in Humboldt County, along the forested North Coast. A fire area adviser with the University of California system, she has traversed the state since then to help another dozen associations to organize.

The groups attract landowners and renters, ranchers and programmers, college students, and retirees. The volunteers receive training from fire ecologists and retired firefighters, learn state and county regulations for lighting fires on private property, and take part in instructional burns.

Ms. Quinn-Davidson, who refers to her work as “almost bordering on activism,” promotes a democratic approach to wildfire prevention and land management. “For so long in the western U.S., fire has been locked in a black box,” she says, drawing a distinction with the Southeast, where public acceptance and use of controlled fire run far higher. “There’s been a belief that only certain people – the federal and state agencies – are qualified to do this.”

Cal Fire provides protection across 31 million acres of privately owned wildlands. As a practical matter, the department lacks the manpower to treat fuels on that much land, and Ms. Quinn-Davidson contends that enlisting trained community members as custodians of fire would lighten the agency’s workload.

Unlike Cal Fire’s burn crews that make sporadic visits to an area, residents can monitor the land season by season, setting small-scale fires when conditions allow. The Humboldt County association has treated more than 1,000 acres, completing burns of three to 350 acres that have targeted brush, grasses, and shrubs, along with dead and downed trees, thinning the kindling that powers wildfires.

The willingness of Cal Fire or air district officials to issue burn permits varies by county. Mr. Brown, who recalls his own skepticism when he belonged to the agency, has gained new perspective since helping launch a prescribed burn association in the county where he lives.

“I understand that hesitation by Cal Fire – you’re responsible if anything goes wrong,” he says. “But the associations are a way to build that relationship between the fire department and the community.”

Wildfire experts speculate that splitting up fire response agencies and forming stand-alone forestry departments would improve land stewardship. The prospects for institutional change of that kind appear small, and Ms. Quinn-Davidson regards the growth of prescribed burn associations and training programs as a more realistic and sustainable remedy.

“It’s hard for any agency to be a steward of such huge pieces of ground,” she says, “and there’s a huge amount of unrealized potential at the local level.”

“It’s about cooperation”

The historic bushfires that ignited in Australia in September last year burned 59 million acres before rains arrived in March. A national inquiry into the catastrophe analyzed the profound effects of climate change and mismanaged forests on fire risk, and emphasized that people need to learn to coexist with wildfire.

Investigators outlined preventive actions familiar to Max Moritz, a wildfire expert with the University of California, Santa Barbara. His research has explored living with fire, a concept that reflects a sense of individual and communal responsibility for wildfire preparedness.

“Fire isn’t going away,” he says. “We have to accept that here in the West and then take the right steps in our communities.”

Wildfires in California have killed 150 people and burned more than 36,000 homes and buildings since 2017. The state’s elastic land-use planning standards magnify the threat by spawning unchecked growth in the wildland-urban interface, broadly defined as areas where development meets natural lands. Studies show that about three-fourths of the homes razed by wildfire statewide fall within those zones, where 11 million people live.

The housing density in fire-prone areas feeds the spread of flames as wind-blown embers flit between homes. The state has attempted to break that chain reaction by requiring the use of fire-resistant building materials for new homes since 2008. Another regulation mandates that homeowners clear dead vegetation within 30 feet of houses to deprive fires of fuel.

The policies adhere to national guidelines for creating fire-adapted communities grounded in mutual awareness among residents and local officials about reducing wildfire danger. But a dual lack of compliance and enforcement has diminished the impact of the laws. Mr. Pyne, the environmental historian, considers this year’s wildfires a chance for state officials to push a message of shared accountability.

“Cal Fire could tell people, ‘Even if we had twice as many water tankers and trucks and firefighters, we couldn’t protect you,’” he says. The cold splash of truth would remind residents of their role in public safety. “It’s about getting out of the mindset that wildfire prevention is someone else’s job.”

A coalition of environmental groups has asked Gov. Gavin Newsom to allocate $500 million in next year’s state budget for wildfire resilience and recovery initiatives. The funding would boost prescribed burning programs and fire prevention efforts to aid homeowners and communities.

A project that could serve as an example for other fire-prone communities has begun to take shape in Paradise, a town of 27,000 people in the Sierra Nevada foothills. Two years after the deadliest fire in state history killed 85 people in and around the town, local officials are acquiring vacant land on its outskirts to form a wildfire buffer zone, seeking to avert future disasters.

Working with Mendocino County’s prescribed burn association, Mr. Brown has found people eager for an education in wildfire. Their interest encourages him. He knows better than most that, for all their powers of suppression, fire crews can fight only so many flames. The infernos of 2020 have shown with harrowing force that everyone in California must recognize the obligations of living with fire.

“We’re all affected by wildfires, so let’s try to help ourselves and each other,” he says. “It’s about cooperation.”

Points of Progress

Lynxes make a comeback

Who doesn't like to hear about progress? This week, our Points of Progress feature includes the comeback of lynxes, a towering new column of coral in the Great Barrier Reef system, and the ingredients for effective peace building.

Lynxes make a comeback

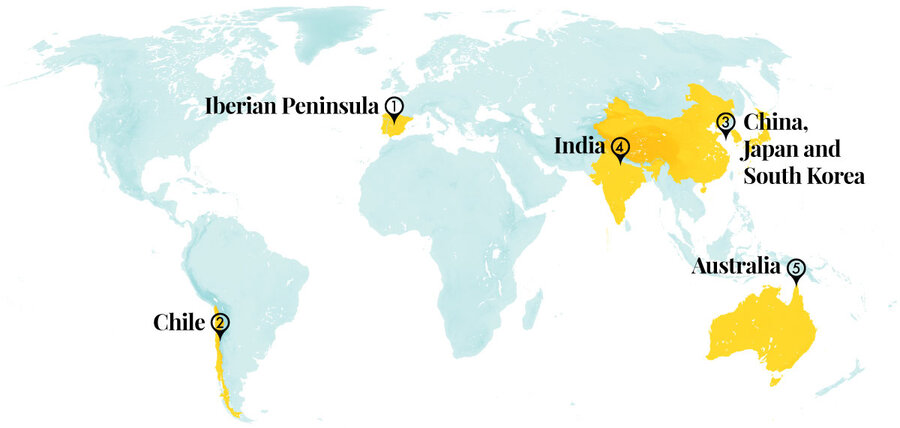

1. Iberian Peninsula

A recent survey found that 311 Iberian lynxes were born in Spain and Portugal last year, continuing the species’ yearslong journey away from the brink of extinction. Iberian lynxes nearly disappeared due to habitat loss, long-retired government policies, and the decline of local rabbit populations, which are the spotted cat’s primary prey. The kittens bring the peninsula’s overall lynx population to 855, marking a 900% increase since the first census in 2002. At this rate, researchers say the species could be fully recovered within two decades.

The latest phase of the reintroduction program, the $22 million Life Lynxconnect project, is supported by the European Union. Ramón Pérez de Ayala, World Wildlife Fund Spain’s coordinator of large carnivores, says it will be necessary to establish new populations in rabbit-rich areas and blend existing populations to encourage genetic diversity. But he’s hopeful about the lynx’s future: “If we can maintain the population growth momentum ... we’ll have at least 750 females of reproductive age – which means more than 3,000 lynxes in total – by 2040.” (The Guardian)

2. Chile

Chileans have overwhelmingly voted to rewrite their constitution, guaranteeing women and Indigenous peoples a seat at the table. Next spring, the country will return to the polls to select members of the constitutional convention. By law, half of those members will be women. The referendum comes after a year of mass protests against the country’s rampant inequality, which many blame on the restrictive constitution created under Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship in 1980.

The landslide victory – nearly 80% of voters called for a new charter drafted solely by Chilean citizens – marks a rare example of a country choosing to rework its constitution without war or political revolution. Experts say many challenges lie ahead, but this groundbreaking vote is the first step in creating a more inclusive and equal country. (The Conversation)

3. China, Japan, and South Korea

China, Japan, and South Korea have all pledged to cut carbon emissions to net-zero in the coming years. In September, Chinese leader Xi Jinping announced plans to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 – a weighty commitment from the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitter. Japan, the fifth-largest emitter of carbon dioxide, then pledged in October to go carbon neutral by 2050, and South Korea followed suit. The latter two countries are now in line with the European Union, which set a similar timeline for reaching carbon neutrality last year. Patricia Espinosa, the United Nations climate chief, said the commitments from China, Japan, and South Korea are “extremely important,” signaling a renewed focus on international climate policy after the pandemic and moves by the U.S. government have derailed diplomatic momentum. “[The pledges] are coming at a time when we need this kind of leadership,” she said. (Thomson Reuters Foundation, Nikkei Review)

4. India

An innovative social enterprise combining clean energy technology and tourism has equipped more than 130 villages in India with solar power and generated $100,000 in income for residents. Global Himalayan Expedition (GHE) finds villages that lack reliable access to electricity and leads tourist treks to help engineers set up solar microgrids and other clean energy fixtures in the remote Himalayan communities. The hikes help pay for the grids and cost up to $3,500 per person. So far more than 1,300 tourists have participated. GHE also trains local women to be electricians and run lucrative homestays where guests can use solar-powered telescopes to stargaze. The United Nations awarded the GHE project a 2020 Global Climate Action Award, citing its potential for replicability in other regions facing similar challenges. (Thomson Reuters Foundation)

5. Australia

Scientists have found a thriving column of coral taller than the Empire State Building – the first new structure of the Great Barrier Reef system discovered in more than 120 years. Studies show the Great Barrier Reef has lost more than 50% of its coral in recent decades, but this new blade-like outcropping off the coast of North Queensland appears healthy. Measuring more than 1,690 feet, the reef is teeming with life, including several species of shark and rare fish.

Remote reefs such as this one are difficult to study, but the deep-sea robots and sonar beams on Falkor, the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s massive research vessel, allowed scientists to create a 3D map of the seabed. “This powerful combination of mapping data and underwater imagery will be used to understand this new reef and its role within the incredible Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area,” said Dr. Jyotika Virmani, the institute’s executive director. (The New York Times, BBC)

World

A new report on effective peace building shows women are crucial to establishing lasting peace. Research by U.N. Women and the Council on Foreign Relations shows that agreements are 64% less likely to fail when women meaningfully participate in the preceding peace talks through civil society groups. Researchers warn that women are still widely excluded from formal peace processes, but data in the report shows some signs of progress. Since 2010, women have made up as much as one-third of the members of peace negotiating teams, according to the United Nations. (Read our related story here.) The qualitative analysis highlighted case studies including the contributions by women on both sides of the 2016 negotiations between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, and the ongoing role of the Women’s Advisory Board for Syria, which is working successfully across political lines to find consensus. (Council on Foreign Relations, Government of the United Kingdom)

In a tough season, how Philadelphia Eagles fans are keeping the faith

What’s a sports fan to do when the cheering is recorded and the attendees are made out of cardboard? Philadelphia Eagles devotees have some tips for adapting.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Before this year, Deb Kurtz went to Eagles games with her 24-year-old son, typically arriving in Philadelphia by 9 a.m. to make the tailgate rounds. With roughly 30 other regulars, they traveled to two or three away games a year.

Not in 2020, of course. For Ms. Kurtz, game day is now all about family. They brought the TV outside and raised a tent for the season opener. Ms. Kurtz’s mom, who spent much of the spring isolated in assisted living, told the family when they were watching the game one recent Sunday, “I love this.”

Here in Philadelphia, the pandemic has segmented the community once flocking to the game and packing bars, Jersey Shore decks, city apartment gatherings, and family parties. But people like Ms. Kurtz are adapting.

They’re looking to the future, too. Next season, Tom Brady’s coming to town with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, and there’s a big on-the-road matchup with the Las Vegas Raiders. “Everyone’s going to Vegas,” predicts Michael Diaz of The Green Legion, which organizes events and travel for Philadelphia sports fans.

Everyone here knows that the thing with feathers is hope.

In a tough season, how Philadelphia Eagles fans are keeping the faith

This is no year to be an Eagles fan, and not only because they’re having such a bad season.

As elsewhere in sports, the coronavirus can dominate the game. Lincoln Financial Field is eerily quiet, its only attendees cardboard, its fan noise engineered. Gone is the team’s anthem, “Fly, Eagles Fly” – a rousing, 70,000-voice love song taught to babies (in good years at least). In normal times, it brings a proud tear to the eye of everyone who was within a snowball’s distance of these parts in 2018. That was when a second-string QB with a silly trick play swiped the Super Bowl from the mighty New England Patriots. That was when fans lined the sidewalks 10 deep for a victory parade and committed to memory the expletive-laden speech from the team’s center Jason Kelce, who dressed in homage to another Philadelphia love: the Mummers Parade.

Maybe you had to be there.

But if social distance is the antithesis of the football experience, maybe the team’s off year is an acceptable time for it. During the few brief weeks some fans were allowed in the stadium, many took a pass. “If you’re not high-fiving, if you’re not tailgating, if you’re not dancing around, I’m really not that interested in it,” explains Michael Diaz, devoted season ticket holder and spokesman for The Green Legion, which organizes events and travel for Philadelphia sports fans.

There’s a lot of “everyone” in sports here, as in, “What’s everyone doing for the game?” But COVID-19 has assailed the hearth around which much of the city gathers on Sundays. (And today, when the Eagles play the Seattle Seahawks in the “Monday Night Football” slot.) The pandemic has broken things down, segmenting the vast and interconnected community once flocking to the game and packing bars, Jersey Shore decks, city apartment gatherings, and family parties. “Fly, Eagles Fly” has become a potential superspreader.

But people are adapting to COVID-19 days. Deb Kurtz of Pennsylvania’s Lancaster County cut her teeth on football, a family passion. She was the game day buddy of her late father, a season ticket holder. The legendary Eagles flanker Tommy McDonald came to her wedding. Now a widow, she’s gone to games with her 24-year-old son, Wyatt, typically arriving in Philly by 9 a.m. to make the tailgate rounds. With roughly 30 other regulars, they’ve traveled to two or three away games a year. There’s also been the occasional wedding of fellow fans, or a special, non-game-related group vacation. These people are family, Ms. Kurtz explains. “I could count on these people. They’d probably give you their last dollar if they had to.”

This year, Ms. Kurtz spends game day with her real family, whose COVID-19 circle is tight. They brought the TV outside and raised a tent for the season opener. Now she heatedly argues football in person with her brother, to the chagrin of her sister-in-law. Her father-in-law, being a Dallas Cowboys fan, is not welcome, or at least that’s what they’re telling people. Her mom, who spent much of the spring isolated in assisted living, told the family when they were watching the game one recent Sunday, “I love this.”

In the bleak days of March, Ms. Kurtz formed a Facebook page for her traveling group, and now they meet each week via Zoom. One Thursday evening this month, they were in no rush to talk Eagles, instead catching up with each other’s week. When talk turned to the recent elections, Ms. Kurtz firmly pivoted to the Birds and the pace picked up, with the same surly commiserating normally done in person: The injuries. The bad trades. The coaching problems. There was profanity, hyperbole, teasing, and trash talk – all the angst of The Fan interspersed with reliving sports highlights past.

What makes football such a magnet? Some say it’s the values: motivation, overcoming adversity, getting knocked down and getting back up. The great Green Bay Packers coach Vince Lombardi famously compared the game to life itself: It “teaches that work, sacrifice, perseverance, competitive drive, selflessness and respect for authority is the price that each and every one of us must pay to achieve any goal that is worthwhile.”

Plus, the game is easy to understand (according to fans, at least). And it’s easy to plan for, since it usually happens on a Sunday. People can disagree vigorously, can argue about play-calling, the pass rush, or other points seemingly trivial without damage to a friendship.

And there’s the overt patriotism – the flyovers, the show of first responder pride, especially the national anthem. Of course the anthem itself has been the center of a controversy so heated that it is widely seen as the cause of NFL ratings declines in recent years. Whether or not taking a knee during the national anthem – a movement Colin Kaepernick began in 2016 to draw attention to racial inequities – is disrespectful to the nation, the flag, or veterans, the injecting of politics into the game alienates many who see sports as a unifier across racial lines.

Business has fallen 90% this year for Joe Abruzzo, longtime owner of Bayou Bar & Grill in Philadelphia, which fans usually pack to the rafters on game day. He believes football’s drift into politics contributed to the drop. Whether the Bayou will survive the virus and the politics is unclear. “People come here to relax and be entertained,” he says, “and it’s really hard for people to come in without bringing in what’s outside – ‘this player said this and this one said that.’”

The fact of being fellow fans typically bridges identity differences, especially when it comes to playing heated rivals. For the Eagles, that would be the all-American, multi-Super Bowl-winning, do-no-wrong Cowboys. “Our livelihoods and our values and the direction of the country don’t depend on the outcomes of ballgames, and a strong geographic/cultural identity and an us-vs.-them mentality actually spice up the whole enterprise,” observed Mike Sielski in his Philadelphia Inquirer sports column recently.

When one city sports executive recently suggested a reimagining of the Philadelphia fan – retiring the lunch bucket, battery-throwing, jail-in-the-stadium stereotype for a “New Philadelphia” narrative focusing on the arts, culture, education, and diversity – he got an old-Philly-style boo. “The blinkered passion for the local teams, the fan base’s long institutional memory, the self-identification as underdogs – is a big part of what makes Philadelphia sports so much fun,” wrote Mr. Sielski.

For some actual, on-field fun, fans here look to the future. Maybe the team will rebuild? Get healthy? Welcome back Travis Fulgham, the receiver who came out of nowhere to become this year’s silver lining? Next season, Tom Brady’s coming to town with the Buccaneers, and there’s a big on-the-road matchup with the Las Vegas Raiders. “Everyone’s going to Vegas,” predicts Mr. Diaz. Everyone here knows that the thing with feathers is hope.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Vivan los artistas de Cuba

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The oldest dictatorship in Latin America just blinked. On Nov. 28, after days of protest by prominent artists and intellectuals over the detention of one of their own, the government in Cuba agreed to grant more independence to the island’s cultural community.

Score one for freedom of thought, the life force of that community’s creativity and its independent expressions, which speak loudly to Cubans trapped under communist rule.

Dictators rarely tolerate protests or “do dialogue” with independent civil society. But in recent weeks, Cuba’s regime has been faced with an unprecedented show of solidarity among a group of artists and thinkers known as the San Isidro Movement. The group has experienced increasing harassment since a 2018 decree made it illegal for artists to operate without being registered with a state institution.

The promised tolerance reflects a recognition of how much Cuban artists are tapping the internet for ideas and reaching foreign audiences. In any country, creative people engage with society to open new possibilities, expand thought, and transcend fear. Cuba’s leaders, who enjoy the international recognition of the country’s rich cultural expressions, may have realized the need for artistic freedom. If so, Cuba is one step closer to democracy.

Vivan los artistas de Cuba

The oldest dictatorship in Latin America just blinked. On Nov. 28, after days of protest by prominent artists and intellectuals over the detention of one of their own, the government in Cuba agreed to grant more independence to the island’s cultural community.

Score one for freedom of thought, the life force of that community’s creativity and its independent expressions, which speak loudly to Cubans trapped under communist rule.

Dictators rarely tolerate protests or “do dialogue” with independent civil society. But in recent weeks, Cuba’s regime has been faced with an unprecedented show of solidarity among a group of artists and thinkers known as the San Isidro Movement. The group has experienced increasing harassment since a 2018 decree made it illegal for artists to operate without being registered with a state institution.

The spark for the protests was the Nov. 9 arrest of rapper Denis Solís, one of many artists whose work challenges the regime’s ideology or its claim to power. To head off escalation of the protests, officials agreed to allow independent creators to meet freely without being “harassed” or “criminalized” by security forces, according to Tania Bruguera, a well-known Cuban artist.

The promised tolerance reflects a recognition of how much young Cuban artists are tapping the internet for ideas and reaching foreign audiences. “The authorities can continue to harass, intimidate, arrest and criminalize alternative artists and thinkers, but they cannot keep their minds in prison,” says Amnesty International’s director for the Americas, Erika Guevara Rosas.

One purpose of art, whether film, dance, literature, or painting, is to help people imagine an alternative reality, perhaps a universal truth that bonds people from different views. Art “expresses feelings for other people who feel the same but maybe don’t know how to articulate it,” Ms. Bruguera told the Financial Times. “Autocratic regimes repress us emotionally. Art liberates us emotionally.”

In any country, creative people engage with society to open new possibilities, expand thought, and transcend fear. Cuba’s leaders, who enjoy the international recognition of the country’s rich cultural expressions, may have realized the need for artistic freedom. If so, Cuba is one step closer to democracy.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Abiding in joy

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

When things get tough, happiness can feel out of reach. But there’s a deep, healing, spiritual joy that God imparts to all of us that we can feel in circumstances of all kinds.

Abiding in joy

“Though the fig tree may not blossom, nor fruit be on the vines; though the labour of the olive may fail, and the fields yield no food; though the flock may be cut off from the fold, and there be no herd in the stalls – yet I will rejoice in the Lord, I will joy in the God of my salvation” (Habakkuk 3:17, 18, New King James Version).

The writer of this Bible verse paints a pretty bleak picture – maybe not unlike the lack and concerns that some are facing today. But as I was reading this recently, the little word “yet” suddenly shone like a light. In spite of nothing yielding any productivity or growth, this prophet, Habakkuk, was joyful.

To me this points to something we can all experience, through prayer: joy stemming from a deeply anchored trust in God’s powerful goodness, regardless of the way things look right at a given moment.

The joy I’m talking about is not grinning and bearing it or a surface “don’t worry, be happy” approach. It is an indispensable and permanent spiritual quality whose substance is found in God, divine Soul – which is another Bible-based name for God highlighted in Christian Science. God gives joy without measure to all of His children. This is a spiritual reality that holds true in all circumstances. Even the gloom of Christianity’s darkest moment – the crucifixion of Jesus – had to ultimately yield to the joy of God’s supremacy seen in the resurrection.

Because such joy is derived from Soul – the one true source of everyone’s spiritual individuality – it is as ever present as Soul itself. It can’t be snatched away by changing circumstances and conditions. Hopelessness and discouragement that would snuff out joy become powerless to influence our thinking when we grasp that God, infinite good, doesn’t cause such feelings.

Is expressing joy consistently too high a goal? For me, there have been days when it’s felt pretty unreachable. But I’ve also seen that joy is in fact attainable even in difficult situations.

While joy can be lively and radiant, I felt it as a quiet steadiness in an experience I had some time ago. I had become ill with a severe cough that included extreme weakness and weight loss. At one point there was a fever that incapacitated me.

Although there were times I felt discouraged, my prayers felt buoyed by a quiet sense of uplifted joy that echoes the biblical idea that God “answers and corresponds to” the joy in our hearts – that “the tranquillity of God is mirrored” in us (Ecclesiastes 5:20, Amplified Bible, Classic Edition).

Mary Baker Eddy who discovered Christian Science, wrote in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures”: “If the disciple is advancing spiritually, he is striving to enter in. He constantly turns away from material sense, and looks towards the imperishable things of Spirit. If honest, he will be in earnest from the start, and gain a little each day in the right direction, till at last he finishes his course with joy” (p. 21).

What this says to me is that the sincere willingness to consistently look to God, Spirit, to light our path brings joy even in the midst of struggles. Whether the experiences of the day are good or not so good, this approach helps keep thought God-focused and open to divine inspiration that heals.

During this period, I felt the value of this. As I prayed, actively affirming God’s caring presence and power, my thought was consistently lifted to a tangible sense of joy and gratitude for and trust in God. It was like a lens through which I saw clearly my unity with God as His loved daughter, purely spiritual and whole. Healing felt inevitable – and when the healing did come, of course I rejoiced.

The situations we find ourselves in can vary enormously, yet we can always cultivate a deep-seated rejoicing in the goodness of God. Such joy keeps us ready and prepared to see the renewing and refreshing power of good pervading every aspect of our lives.

Some more great ideas! To hear a podcast discussion about how you can support our military with healing prayer, please click through to the latest edition of Sentinel Watch on www.JSH-Online.com titled, “Praying with and for the military.” There is no paywall for this podcast.

A message of love

Just the right size

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Join us tomorrow for Lindsey McGinnis’ exploration of Parler, the new social media platform that conservatives are flocking to.