- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- National debt is surging higher. Here’s why worry is heading lower.

- Suicides fell in 2020, defying predictions in a year of loss

- Should school lunches be free for all? A pandemic experiment.

- Pride or prejudice? ‘The Eyes of Texas’ now a racial lightning rod.

- Black master falconer helps birds and at-risk youth take flight

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

When fairness becomes a community response

It wasn’t the waitress’s fault. But she bore the cost.

At each table in the Glenbrook Brewery in Morristown, New Jersey, there is a sign that says seating is limited to 90 minutes due to COVID-19 capacity restrictions – currently at 50% in the state. It’s a common practice. Time limits allow restaurants to turn over as many tables as possible in hopes of making a profit. In the U.S., an estimated 110,000 restaurants have gone out of business during the pandemic.

After an $86 meal for four last Friday, a disgruntled Glenbrook patron left no tip for his server, a nurse in graduate school working more than one job. Scrawled on the receipt: “Don’t kick paying customers out after 90 minutes.”

But the story doesn’t end there. When a photo of the receipt with the word “zero” on the tip line was posted on a community Facebook page by a waitress from another establishment, folks responded. A local business owner started collecting tips – nearly $2,000 – for the stiffed server.

“The public support and outpouring, the kind comments, just the things people say bring me to tears,” the waitress, Beth (she didn’t give her last name), told NBC New York. She plans to share 20% of the total with her fellow servers, and give the rest back to the community.

The natural response to injustice is compassion, empathy, and a desire to help.

Nicely done, Morristown.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

National debt is surging higher. Here’s why worry is heading lower.

Even as the U.S. tallies record national debts, we look at why some economists have shifted their views about the dangers of big debt. At least, for now.

While the economy is roaring back and the pandemic looks like it might finally ease, one troubling trend remains: The United States is piling up debt as never before. Federal deficits in 2020 and 2021 are certain to be the biggest relative to gross domestic product since World War II. By 2031, the federal debt will reach an all-time record share of the nation’s economy, the Congressional Budget Office forecasts, even if current spending doesn’t change.

Yet economists appear less concerned than they were five years ago. And Democrats and even some Republican policymakers have plans for even more government spending. One reason is that economic recovery has trumped debt concerns. Another is that interest rates are so low that the costs of government borrowing are almost nil.

The big question is how lasting these shifts in policy really are. No one knows, but Alan Viard of the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute predicts, “The political parties will continue to do their cyclical thing: ‘Your deficits are bad. My deficits are good.’” Absent a bipartisan consensus to keep a lid on spending, the debt will continue to grow.

National debt is surging higher. Here’s why worry is heading lower.

Like the swallows to Mission San Juan Capistrano and the buzzards to Hinckley, Ohio, the doves on government debt have returned to Washington.

And in a big way.

The numbers tell the story. Last year, in the face of a once-in-a-century health emergency, a Republican president pushed massive spending bills that pushed the federal deficit to 14.9% of gross domestic product, the biggest shortfall of any year since 1945, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). This year, spending was forecast to reach 10.3% of GDP, the second-largest deficit in that era, even before the stimulus sought by his Democratic successor kicked in and other big spending measures are proposed.

In the past, both these presidents cast themselves as budget-cutters. And their supporters in Congress have dutifully gotten behind the big spending bills. Now, on the far left, congressional Democrats are pushing for even more deficit spending in line with so-called modern monetary theory, in which deficits don’t really matter for nations, like the United States, that print their own currency. And some Republicans are sending up trial balloons advocating increases in government outlays.

How long this debt-friendly climate lasts will hinge on political and economic factors that are hard to predict. When their own party is in power, politicians on both sides of the aisle have become prone to forget about the mounting federal debt. When they’re out of power, deficits and debt take on importance as an argument against the other side’s priorities.

As the pandemic emergency passes, “the political parties will continue to do their cyclical thing: ‘Your deficits are bad. My deficits are good,’” predicts Alan Viard, an economist at the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute (AEI).

Yet for now, the pandemic and a sharp recession, coupled with a long period of low interest rates, have clearly changed the dynamics of fiscal policy.

What has changed, most notably, is the consensus among many economists. Whereas a few years ago, a key concern was the level of debt relative to GDP, with 90% to 100% considered a danger zone, now many are less worried about it.

“The economics field has shifted,” says Heidi Shierholz, director of policy at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute and former chief economist to the secretary of labor during the Obama administration.

Clearly, the nation is piling up debt, which reached 100% of GDP last year and by 2031 was on track to reach a record 107%, even before the Biden administration’s stimulus package was passed, according to the CBO. But two things have changed.

First, interest rates have fallen to near record lows, making the cost of borrowing virtually free. That could prove a boon, especially if the money is spent on investments, such as infrastructure, that can grow the economy in the future.

“Investing in better roads, bridges, dams, electrical infrastructure, all of that stuff, clearly, those investments pay returns over a long period of time,” says Leonard Burman, a professor at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School in New York. “Investing in better education, if you can do it, pays returns over the course of decades.”

Second, the slow recovery from the Great Recession has convinced many economists that the U.S. didn’t enact enough stimulus at the time. In the face of opposition from Republicans and concerned about ballooning the federal debt, President Barack Obama and then-Vice President Joe Biden cut back their stimulus proposal. Democrats don’t want to make the same mistake twice.

“We were piling up this evidence that we weren’t doing what we needed to do,” says Ms. Shierholz. “We need to deficit-spend.”

So far, President Biden is doing just that. Having pushed through a $1.9 trillion stimulus package last month, he is now proposing a $2 trillion infrastructure and green energy plan. Other expensive initiatives on health care and education are in the works.

Unusually, he is proposing tax increases on corporations and the wealthy to pay for the infrastructure package over 15 years – a sign that Mr. Biden, who spent his Senate career championing budget restraint, has not cast his lot with the far left wing in his party. This group has gained momentum in recent years with its new and unproven fiscal approach, modern monetary theory.

This view has received some validation because conventional theory can’t explain why interest rates have stayed so low while government borrowing has soared so high. But some economists liken it to the left’s version of supply-side economics, under which some conservatives have argued without evidence that tax cuts pay for themselves.

Conservative politicians have also been embracing looser fiscal policies.

“Republicans have not exactly been ones to shy away from increased spending on national security – they’ve always had that bent,” says William Hoagland, former Republican staff director of the Senate Budget Committee and now senior vice president at the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington. Then, he adds, a series of national crises this century – from 9/11 to the Great Recession – caused the GOP to repeatedly shelve plans to trim spending and, instead, ratchet it up, he says.

This lack of fiscal discipline was most prominent during the Trump administration, which pushed through large tax cuts without taking on major entitlement programs.

Although the proposed Biden tax increases are unpopular with conservatives, Republicans have signaled their support for parts of the infrastructure plan. Interviewed on Sunday, GOP Sen. Roy Blunt of Missouri predicted the president would have “an easy win” if he would scale back his $2 trillion infrastructure bill by two-thirds. That’s roughly the amount that the proposal would spend on traditional infrastructure.

But the Biden administration has stretched the definition of infrastructure to include building and rehabilitating housing for low- and middle-income Americans, upgrading public schools and community colleges, and expanding home-based care for seniors.

At some point, a rise in interest rates could challenge the new thinking about debt. Jason Furman and Lawrence Summers, prominent economists who have served in Democratic administrations, wrote last fall that “current projections do raise concerns over the fiscal situation beyond 2030,” but they added that “there is enormous uncertainty and ... much of the issue would be addressed if necessary reforms internal to Social Security and Medicare were undertaken.”

At present, the focus is squarely on economic revival, not entitlement reform. Yet even now, the administration had to push through its stimulus program through Congress without a single Republican vote. Pundits expect an uphill battle for Mr. Biden’s infrastructure plan.

This extreme partisanship dims the prospects for tackling the nation’s deficits and debt anytime soon. “I’ve become more pessimistic in recent years because addressing this problem before there’s a crisis is going to require bipartisan agreement,” says Mr. Viard of AEI.

Partisanship may actually be making the debt problem worse.

“Polarization has killed the kinds of days we used to have where people of both parties could come together and hammer out tough deficit deals because they knew it was the right thing to do,” says Maya MacGuineas, head of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a nonpartisan, nonprofit group in Washington. “Now, party leaders and many members of the parties are so focused on every new political battle and election, they’re unwilling to do the hard work of governing. [And] politicians tend to get more support by giving things away rather than actually paying for them.”

Staff writer Christa Case Bryant contributed to this article from Washington.

Points of Progress

Suicides fell in 2020, defying predictions in a year of loss

We like to explore the unexpected. In this case, amid all of the challenges of the pandemic, and dark forecasts, here’s some light: The U.S. suicide rate this past year took a turn for the better.

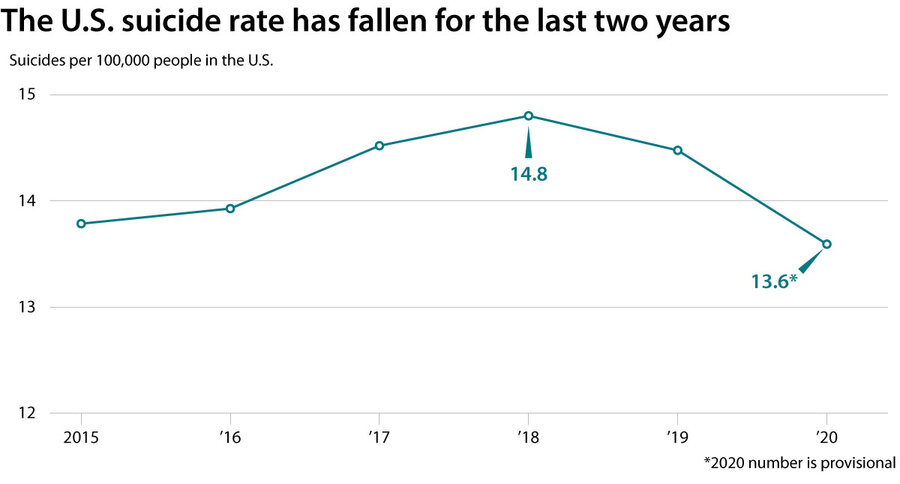

Despite concern that the pandemic would lead to a spike in self-harm, deaths from suicide last year fell to a five-year low, according to a new report from the National Vital Statistics System at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dropping from 47,511 to 44,834 – a 5.6% decrease – the total number of suicides in 2020 marked a second straight year of decline, after three consecutive years of increase.

The report’s numbers are still provisional and full data, complete with demographic breakdowns, won’t be available until late this year. The reasons for the decline are not yet clear. Notwithstanding, the decrease marks a rare bit of good health news in 2020, says lead author and health scientist Farida Ahmad.

She cautions that 2020 is difficult to compare to other years. Still, “given a lot of the chatter about mental health and the conversation surrounding it” last year, she says, the total runs counter to what she initially expected.

While total deaths rose precipitously in 2020 due to the pandemic, Americans can take the drop in self-harm as encouragement amid a year of loss. – Noah Robertson, Staff writer

National Center for Health Statistics; U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division

Should school lunches be free for all? A pandemic experiment.

What does a national experiment in giving all children – regardless of family income – free meals at public schools look like? The pandemic offers us a live test of what works, or doesn’t.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Ever since March 2020, when the pandemic was declared, schools across the United States have been ground zero in a massive, accidental experiment in universal free meals. All public school children are for the first time experiencing equal access to food, no questions asked.

But the idea of providing universal free meals requires a certain shift in thought – and budgets – that not everyone agrees with.

“The National School Lunch Program was created to provide meals for children from low-income families, period,” says Jonathan Butcher, who researches education policy at the conservative-leaning Heritage Foundation. While opening up eligibility during the pandemic might make sense, previous expansions – and the prospect of making the current one permanent – have resulted in programs straying from their origins and providing meals to people who don’t want or need them, he says.

By contrast, universal free meals make perfect sense to Hattie Johnson, director of nutrition services for Monroe County Community School Corporation in Bloomington, Indiana. “If we’re supposed to treat all kids the same, if public education is supposed to be free, and we know that the kids can’t make it through the school day without having something to eat, then why isn’t it a part of a free education?”

Should school lunches be free for all? A pandemic experiment.

It’s 5 p.m. on a Tuesday, and Cathy McNair and a few student volunteers are ready to go. They’ve wheeled out a couple dozen boxes of pre-packaged meals – some donated and some from the school’s food services provider – to the Finneytown Secondary Campus parking lot in suburban Cincinnati.

High school and middle school students here are attending class on a hybrid model – partially in person, partially remote. But students need to eat regardless, so the questions arise: If they’re not getting their meals at school, how are they getting them? Are they getting them?

Ms. McNair, the school social worker, and her team set up shop multiple times a week to hand out free school meals to anyone who wants them. Parents pull up, drive-thru style, to maintain social distancing.

“I love it. I absolutely love it,” says Christina, a mother of four, who asks that her last name be withheld in order to feel comfortable talking about her family’s financial situation. Without the meals, she says, “it would be a lot more stressful. A lot more of me monitoring – ‘Alright, you can have this much milk today.’”

Despite myriad programs – free and reduced-price school breakfasts, lunches, and after-school meals, as well as benefits like SNAP (formerly known as food stamps) – 11 million children in the United States lived in “food insecure” homes before the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the advocacy group No Kid Hungry. Amid predictions that number could reach 18 million during the pandemic, restrictions on how poor a family had to be to qualify for free school meals were lifted – opening up the program to all.

Since March 2020, schools across the country have been ground zero in a massive, accidental experiment in universal free meals.

The results aren’t perfect, advocates say, but it’s opened up new ground in a debate on how to make sure each American child has enough to eat every day.

As a result of the expansion of the meal programs, advocates say, working poor people can now get the help they need, and families don’t feel singled out for receiving free meals. After more than a year under this temporary system, some are seeing a new, permanent path emerging for universal free school meals.

Others see a new entitlement creeping up in place of a targeted poverty-reduction program and want to return to the previous system if the expansion expires in September as planned. In the meantime, all public school children – in one of the world’s wealthiest nations – are for the first time experiencing equal access to food, no questions asked.

“Personally, I think it would be great if we had food, and if kids wanted food, they got food,” says Ms. McNair. At the Tuesday meal distribution, she spots a student leaving an extracurricular activity and asks if he wants a meal. He hesitates at first, but takes one. Without missing a beat, Ms. McNair asks him, “Just one? Do you have siblings at home?”

Stigma-free food or undue entitlement?

In a normal year, free or reduced-price school meals were a lifeline for students from low-income families. Schools – or the companies they contract with to provide food – could get reimbursed by the federal government for the free and reduced-price meals they offered. But there was a strict income threshold for eligibility.

For Christina and her family, who have depended on free school lunches off and on over the years, lifting the eligibility requirements also lifted a huge mental burden as she and her husband faced unemployment and underemployment amid the pandemic’s devastating economic toll.

“There’s a stigma behind a free lunch,” says Christina, picking up her meals at the Finneytown Secondary Campus. “Some kids are embarrassed that they’re on that free lunch. And so, with everybody having it, there’s not that stigma behind it.”

Her family certainly isn’t alone.

The pre-pandemic eligibility rules inevitably meant some students weren’t getting the assistance they needed. Gerry Levy, nutrition services director for several Cincinnati-area school districts, rattles off examples: children of working poor people who made just a bit too much money to be eligible, those who can’t read English and didn’t turn in the forms, and those who were too embarrassed to ask for help. For Ms. Levy, the expansion has been “ideal.”

But the idea of providing universal free meals requires a certain shift in thought – and budgets – that not everyone agrees with. One Indianapolis-area public school contacted by the Monitor, for example, was hesitant to comment on its meal expansions. The administrator voiced concerns over how members of the community, located in a politically conservative area, would react to the fact that people who didn’t need free meals might be getting them.

“The National School Lunch Program was created to provide meals for children from low-income families, period,” says Jonathan Butcher, who researches education policy at the conservative-leaning Heritage Foundation. While opening up eligibility during the pandemic might make sense, previous expansions – and the prospect of making the current one permanent – have resulted in programs straying from their origins and providing meals to people who don’t want or need them, he says.

When it comes to shoring up the previous system, “let’s make a program that is going to help those in need as effectively as possible,” Mr. Butcher says. “Making school meals universal creates an entitlement – it essentially gives up on the idea that we should be concerned about accuracy.”

“All of a sudden we can afford it”

Hattie Johnson, director of nutrition services for Monroe County Community School Corporation (MCCSC) in Bloomington, Indiana, knows something about crunching numbers.

Before the pandemic, during the 2019-20 school year, Ms. Johnson’s school system was on track to rack up nearly $100,000 in school lunch debt, accrued from students not paying for their lunches.

When students pass through the lunch line without any cash, schools usually serve them anyway and document the money the family needs to pay back. When it’s a kid who forgot her lunch money, that’s no big deal. When it’s a family struggling to make ends meet – but ineligible for free meals – schools are stuck chasing after money from people who don’t have it. In recent years, the MCCSC has turned to a local charitable foundation and the federal government to help reconcile the negative balance.

But this past school year brought a completely unexpected test: Can the nation actually afford to offer free school lunch? Ever since March 2020, MCCSC has done just that, and its school lunch debt problem has essentially disappeared.

“I’ve been in school meals since 1993. And when I came in ... the big push was universal feeding” – that is, free school meals for all, regardless of income, says Ms. Johnson. “For a gazillion years, [the United States Department of Agriculture] would say we cannot afford it. Then, COVID. And all of a sudden we can afford it.”

This spring, there aren’t as many free meals being served as Ms. Johnson would have expected – children have returned to classrooms, but some families are still remote, and not all are picking up meals. Others are packing lunch, out of COVID-19 concerns. But the results of this year’s experiment in universal free meals are clear – at least to her.

“If we’re supposed to treat all kids the same, if public education is supposed to be free, and we know that the kids can’t make it through the school day without having something to eat, then why isn’t it a part of a free education?”

A letter from

Pride or prejudice? ‘The Eyes of Texas’ now a racial lightning rod.

The University of Texas has been swept up in the nation’s racial reckoning. We look at the challenge of embracing unity today with an official song that’s seen as a cherished tradition and, by some, as divisive.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

As Robert Reeves’ baby son cried for the first time in his arms, the new father grasped for the most soothing thing he could think of: He sang the University of Texas at Austin spirit song – “The Eyes of Texas.”

Bound in memories, emotion, and fierce pride, the song has been the source of an agonizing debate here over the song’s origin in the racist era at the turn of the 20th century, when the then-UT president told students that “the eyes of Texas” were upon them – a call to make the most of their education.

Rocked by protests and boycotts, soul-searching and bullying, historical detective work and threats by donors to withhold funding, the administration stands by the song. It commissioned a scholarly study that determined the lyrics are not “overtly racist,” even if they did arise in a racist era. The rebuttal of one university historian, though, argues that while the song may not be intended as racist today, racism is its origin.

For his part, Mr. Reeves – a high-tech entrepreneur and donor to the school – wrote in an online post that he supports a change. Tradition, he wrote, “is just something you have done for a long time. ... To be a Longhorn means much more than a song.”

Pride or prejudice? ‘The Eyes of Texas’ now a racial lightning rod.

The pop of softballs hitting leather gloves faded away, and as the University of Texas at Austin players lined up on the third base line last month, the first stirring notes of the school’s official song blared out of speakers.

“The eyes of Texas are upon you,” the crowd sang, like generations of Longhorns have before them. “You cannot get away.”

There were no signs of dissent or disapproval in the crowd – but the century-old lyrics have become a front in America’s culture war, and a manifestation of the nation’s post-George Floyd racial reckoning.

Since last summer, protests against racial injustice have demanded changes in policy and in politics – but also changes in tradition. While politics and policy are often subject to change, tradition, by definition, isn’t – like the official song of the Lone Star State’s flagship university.

Around the turn of the 20th century, then-UT President William Prather often told students that “the eyes of Texas” were upon them – a call to make the most of their education. It stuck, inspiring a song now intertwined with generations of memories and emotions.

But for some Longhorns, it’s a source of discomfort. Though the lyrics are not explicitly racist, they point to its ties with the Confederacy and blackface. A song that provokes feelings of disgust and dehumanization, not pride, they say, shouldn’t be the school’s official song.

It has been the source of an agonizing debate here – with protests and boycotts, soul-searching and bullying, historical detective work and threats by donors to withhold funding.

It’s not a new debate, but until this year the main allegations – that the title was inspired by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee and it was performed at minstrel shows more than 100 years ago where students would often wear blackface – had not been forensically examined.

So when some alumni and students – including some Black athletes – last summer called for replacing the song and not requiring players to sing it, UT President Jay Hartzell responded by commissioning an academic study of the song’s history.

Eight months later, the study concluded it was very unlikely that the lyrics originated with General Lee, and that while the song “probably debuted in blackface” at a minstrel show in 1903, it had been written earlier. While the song was created in a racist setting, the report concluded, it wasn’t “overtly racist.”

“I saw [the report] and thought, it’s not enough,” says Alberto Martinez, a history professor at the university. He spent 15 days last month doing his own research on the history of “The Eyes” and he has some bones to pick.

Specifically, Dr. Martinez traces the title to a Confederate war story that President Prather likely heard. Before charging the enemy in an 1864 battle, the Texas Regiment heard that “the eyes of General Lee are upon you.” He also cites primary sources that indicate the song had been written for the 1903 minstrel show, on the day of its performance.

“That is not what the song presently is, and that is not how most singers intend it. But those are its origins,” concluded Dr. Martinez in his report.

“I’m not a fan of cancel culture,” he says. “This is not a song that generates enough unity to continue being the official song of UT.”

While he’s been criticized by supporters of the song, he’s not yet had a response from the university about it.

The authors of the UT report, for one, say they want their research “to start a conversation.” Though the university has stated that “The Eyes of Texas” will remain the official fight song, the historical study said that “from its inception [the song] has always been a song about accountability … [compelling] the university to be transparent about its past and be ever more accountable to the state and its diverse people.”

Emails from powerful donors and alumni to university leadership last June obtained by the The Texas Tribune included direct threats to withhold funding to the school if “The Eyes” was dropped as the official song.

Among the emails was one from donor and alumnus Robert Reeves, a tech entrepreneur in Austin. He argued that even while “The Eyes” has been the soundtrack to his most cherished memories – including as a lullaby to his newborn son at bedtime – current students should be allowed to define the school as they see fit. So he offered to help make up the difference of funding lost if the song were dropped.

Tradition “is just something you have done for a long time,” he wrote in a post online last June. “To be a Longhorn means much more than a song.”

Difference-maker

Black master falconer helps birds and at-risk youth take flight

As master falconer, who grew up in the city, he’s an empathetic teacher who knows personally the value of second chances – and how humans can learn about trust from birds of prey.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

With a mother who struggled with heavy substance use, Rodney Stotts grew up in southeast Washington during the crack epidemic. By early adulthood, he reflected his circumstances – dealing drugs and on course to cross up with law enforcement, he says.

Then, by accident, he found work with raptors, rehabilitating injured birds of prey and using them for environmental education at Earth Conservation Corps, a nonprofit then focused on cleaning the notoriously polluted Anacostia River.

“The first time I held a bird, period, it took me somewhere else,” says Mr. Stotts, who became head of the raptor program at ECC, where he continues to work sandwiched between two institutions for at-risk youth.

In the three decades since, Mr. Stotts has worked with thousands of people on the streets and in schools, parks, jails, barns, and Zoom calls.

Along the way, he founded his own nonprofit, Rodney’s Raptors, and earned his falconry license. Along with his four Harris’ hawks and one red-tailed hawk, he works with at-risk youth, giving them an outlet, a role model, and a chance to learn to trust others by learning to trust animals.

Black master falconer helps birds and at-risk youth take flight

Before young Jamaal Hyatt met falconer Rodney Stotts, the youth had never seen a bird fly from a person’s finger, disappear out of sight, and return at the sound of a whistle. He’d never fed a bird of prey, or understood the trust it takes for one to calmly perch on a person’s arm. He’d never even seen a raptor up close.

Mr. Hyatt grew up in downtown Washington, D.C., where birds rest on traffic lights as often as trees. Two years ago, when his family felt he wasn’t focused on school, they decided to send him to Capital Guardian Youth Challenge Academy, a military school for at-risk students in Washington high schools. It was in the woods here that he met Mr. Stotts – a master falconer, mentor, conservationist, and Dr. Dolittle of sorts.

Mr. Stotts, too, grew up in Washington, and, like Mr. Hyatt, once barely knew a pigeon from a peregrine falcon. But more than 30 years ago, working with animals transformed him from a man of the streets to a man of the woods. He’s since become a mentor for young people facing similar challenges.

That mission brought him to Laurel, where his office is sandwiched between Capital Guardian and New Beginnings Youth Development Center, a youth detention and rehabilitation facility. He works with young people in each facility, giving them an outlet, a role model, and a chance to learn to trust others by learning to trust animals.

“A lot of kids don’t really experience that [kind of connection with animals firsthand],” says Mr. Hyatt, who graduated from Capital Guardian in 2019. “It made me want to get a pet.”

In three decades Mr. Stotts has worked with thousands of people on the streets and in schools, parks, jails, barns, and Zoom calls. Along the way, he founded his own nonprofit, Rodney’s Raptors, and earned his falconry license. The work is low in pay and often poignant, forcing him to confront violence, substance misuse, and loss.

But for Mr. Stotts, whose life is profiled in a new documentary, “The Falconer,” it’s highest in personal reward. If he could change, he tells the young people he works with, so can they.

“I would see how a young person was [struggling to find direction]. It was the same as that bird,” says the falconer.

Transported “somewhere else”

With a mother who struggled with heavy substance use (before later quitting cold turkey), Mr. Stotts grew up in southeast Washington during the crack epidemic. In early adulthood, he reflected his circumstances; he dealt drugs and was likely to cross up with law enforcement, he says. Then, by accident, he found animals.

In the early 1990s, he needed a pay stub to sign on an apartment and took a position at Earth Conservation Corps (ECC), a nonprofit then focused on cleaning the notoriously polluted Anacostia River. Bob Nixon, the program’s de facto founder and a falconer himself, helped introduce Mr. Stotts to animals and eventually birds of prey.

“The first time I held a bird, period, it took me somewhere else,” says Mr. Stotts.

His early work with raptors at ECC involved rehabilitating injured birds of prey and using them for environmental education. Most raptors don’t live to adulthood, and he learned how a simple intervention could help them survive. He couldn’t help see it as a metaphor for his own life.

“As I was changing from working with the birds and everything and seeing myself change, I couldn’t go back to doing anything else,” Mr. Stotts says.

After a year, he stayed with ECC and eventually took charge of its raptor program, based in Laurel. The ECC’s proximity to Capital Guardian and New Beginnings led to a partnership with each facility. Mr. Stotts’ testimony and persistence have made those partnerships fruitful.

“He’s been engaged since the get-go – that’s the impressive thing,” says Mr. Nixon, of ECC. “He really feels the nature in his bones and gets a real reward in sharing that with people.”

Talons and kisses

Sharing that interest isn’t easy. When donations run short, Mr. Stotts funds his work himself – even on unemployment aid during the pandemic. To reach the ECC campus here, Mr. Stotts drives his rickety pickup truck, 240,000 miles and counting, from his seven-acre plot in Charlotte Court House, Virginia, a four-hour trip. The campus consists of two barns, where his four Harris’ hawks and one red-tailed hawk have separate 512-cubic-foot aviaries. Like all of his birds, they’re named for loved ones who have died – a reminder, he says, that people are looking out for him from above.

With his falconry license, Mr. Stotts is able to trap new juvenile raptors each year and release them once they reach maturity and have a better chance to survive alone. That process is all about building trust.

Raptors are by nature defensive, and an untrained visitor likely couldn’t exit an aviary without talon marks. But by taking small steps and rewarding them with food – most often mice donated by the nearby National Institutes of Health – Mr. Stotts can bond with them to the point they’ll rest comfortably on his arm. Sometimes, he can even kiss them.

The young people he works with require a similar, gradual effort.

In his weekly two-hour sessions with Mr. Stotts, Mr. Hyatt and a group of other students at Capital Guardian would take the short trip off campus to help care for Mr. Stotts’ animals and clean up. Occasionally they would get to walk horses or feed the birds, though some fret at getting so close to a raptor. The trips, says Mr. Hyatt, were a welcome break from the norm.

“I’d never experienced that before,” says Mr. Hyatt. “I’d never seen or pet any horses or other animals like that.”

In Mr. Stotts, the young people also have a role model who walks his talk. He came from similar circumstances and can understand lingering trials.

While earning his falconry license in the early 2010s, he encountered people who thought “it was an oxymoron to hear ‘Black falconer,’” he says. One person told him Black people eat birds, not fly them.

“There’s a lot of kids out here that don’t really have anything or don’t even believe in [themselves],” says Mr. Hyatt. “Seeing somebody like that ... can uplift them and give them a little bit more hope.”

In 2006, Hollis Wright needed that hope. At that time, he was 19, volunteering with ECC, and living on the edge of the law. Like many young men who came out of underserved parts of Washington, he says, he acted tough. And like many in the program, he’d heard nothing but praise for Mr. Stotts.

“It was like he was this mythical creature, almost,” says Mr. Wright.

At one point, Mr. Stotts shared his testimony with the class. Afterward, Mr. Stotts laughed, hearing Mr. Wright blustering in front of the group.

“What’s so funny?” Mr. Wright asked.

“Y’all are stupid,” Mr. Stotts said, puncturing his tough-guy act.

Taken aback, Mr. Wright stepped aside to talk to him. At the end, the younger man asked Mr. Stotts to treat him like family. To this day, Mr. Stotts calls Mr. Wright his “nephew.”

Over time, that relationship helped Mr. Wright confront problems with anger, trust, and his family. More than 15 years later, he has a stable career in law enforcement and a family of his own. He credits Mr. Stotts: “I was a bird with the broken wing when he met me. He took the time and he took the effort to show me that it’s OK to trust, that it’s OK to allow someone to help me heal.”

To learn more about Rodney’s Raptors, visit www.rodneysraptors.webs.com.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Tax avoidance gets the world’s attention

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A favorite research topic among economists is whether countries are able to improve their tax collection, especially in curbing legal tax avoidance. Soon this topic could be global. On April 7, the finance ministers of the Group of 20 nations said they hope to agree soon on a way to prevent one of the most common tax-avoidance schemes: corporations shifting their profits or legal identity to a low-tax country.

In theory, the G-20 endorsed a global minimum corporate tax rate that might prevent such “tax shopping” – and the resulting competition among nations to lower their tax rates. Its move was made easier by a decision last week from the Biden administration. A minimum rate would help “make sure the global economy thrives based on a more level playing field,” said Janet Yellen, President Joe Biden’s treasury secretary.

While countries need greater transparency and enhanced accountability in tax collection, states a new United Nations report, all people in a country must contribute “towards financial integrity in all aspects of their lives.” Corporations might seem like abstract entities, but they are made up of individuals who can live up to that goal.

Tax avoidance gets the world’s attention

A favorite research topic among economists is whether countries are able to improve their tax collection, especially in curbing legal tax avoidance (“loopholes”) by citizens and corporations. The former Soviet state of Georgia, for example, was recently commended by the International Monetary Fund for a rapid rise in tax revenue. Its reform, said the IMF, required “first and foremost a broad social and political commitment.”

Soon this topic could be global. On April 7, the finance ministers of the world’s wealthiest nations (the Group of 20) said they hope to agree by mid-2021 on a way to prevent one of the most common tax-avoidance schemes: corporations shifting their profits or legal identity to a low-tax country, or even a no-tax “haven” like the Cayman Islands.

In theory, the G-20 endorsed a global minimum corporate tax rate that might prevent such “tax shopping” – and the resulting competition among nations to lower their tax rates. Agreeing on a specific rate, however, could be difficult, as would enforcing it. Many countries now do legal somersaults to lure foreign investment.

The G-20’s move was made easier by a decision last week from the Biden administration. A minimum rate would help “make sure the global economy thrives based on a more level playing field,” said Janet Yellen, President Joe Biden’s treasury secretary and a former head of the Federal Reserve. With such a global standard, President Biden hopes American corporations will keep more of their money in the United States, thus funding his ambitious spending plans.

The idea of a global tax rate has gained in popularity because of the rapid globalization of commerce as well as the rise of digital companies that can easily operate across borders. And with the pandemic draining government budgets, countries are even more eager to find new revenue. On April 6, the IMF’s managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, called on political leaders to “collect taxes more effectively.”

Much of the groundwork in finding a consensus on corporate taxation has been done by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a club of mostly rich countries that helps set global norms. Not to be outdone, the United Nations issued a report in February that looked at the “gaps, loopholes and shortcomings” in how countries finance themselves. While offering dozens of recommendations, the report said tax abuse arises from a “weakness of social contracts” and “incentives that divert taxpayers (both corporate and individual) away from society’s goals.”

While countries need greater transparency and enhanced accountability in tax collection, stated the U.N. report, all people in a country must contribute “towards financial integrity in all aspects of their lives.”

Corporations might seem like abstract entities, but they are made up of individuals who can live up to that goal. If the G-20 agrees on global rules for taxation, it might raise the bar on tax integrity. Perhaps then avoiding a tax bill, even if done legally, might seem outside the bounds of a country’s social contract.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Am I good enough?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Kim Crooks Korinek

When nagging concerns about her ability and worth reared their head, a woman found confidence and inspiration from the realization that God has given us all the intelligence, love, and ability we need.

Am I good enough?

My contribution for the work project had been turned down ... again. I felt defeated. And the nagging question “Am I good enough?” raised its ugly head. It’s a question that can plague anyone struggling with self-doubt and fears of others seeing you as inadequate.

This question used to hit me frequently. But over time, I’ve learned that an effective way to combat this pesky question is by turning it around – not focusing on what I’m lacking, but instead asking, “What am I being?”

For me that question is best answered by exploring the nature of God and our relation to God. In that light, each of us is spiritual, capable, and resilient. We are good enough because God is good enough, and God’s goodness is expressed in all His children.

Christian Science teaches that God fills all space. God is the source of all love, and imparts throughout creation the intelligence of divine Mind, the substance of infinite Soul, and the purity and power of Truth. The Bible instructs us to “acquaint” ourselves with God, “and be at peace” (Job 22:21). By discovering more of God’s all-inclusive love, we can be at peace and freely love all that God creates, and that includes ourselves as well as each other.

God, our Father-Mother, loves His creation thoroughly and has created us in His image. Our oneness with divine Love, God, is the key idea that helped my thought shift from doubt to confidence. I reasoned, Can a ray of light be separated from its light source? Likewise, it is impossible for us to be separated from the divine Love that created us.

Christ Jesus had such a clear awareness of his oneness with God. He knew God’s love and supreme power. His constant communion with God gave him his healing authority and conscious worth. He said: “I know where I have come from and where I am going” (John 8:14, New Revised Standard Version). He also said, “I and my Father are one” (John 10:30). He made it clear that we should all understand ourselves to be at one with God. He proved that we are inseparable from the Divine – as Soul’s representative, with Soul’s resources of beauty, honor, intelligence, and grace ever at hand.

Knowing ourselves in this way also means loving ourselves as God loves us. Discerning our spiritual origin and God-given purpose wipes out feelings of inferiority stemming from a sense of identity based on personality, fears, and doubts. The pull to unhelpfully compare oneself to others is replaced when we realize that God’s children are not limited in their access to God’s goodness, nor do they clash, compete, or take away another’s light. As God is Love, we are created to be loving. As God is Soul, we are capable. As God is Mind, we are intelligent.

Turning the question “Am I good enough?” to “What am I being?” and considering all that God knows about me flipped a switch in my approach to the work project. I was able to resume working on it, inspired and refreshed. Anxiety was replaced by a holy curiosity about how Love would inspire me to express the right ideas and complete the project successfully. I realized I had all the spiritual qualities needed to do whatever is my duty to do. And soon my part of the project was accepted by the rest of the group.

In my life, I’ve found time and again that whatever the demands, these same spiritual ideas about our oneness with God are constant, fundamental, and true. They are here to rescue us from being duped into believing that we are less than we are, or becoming preoccupied with compensating for a perceived fault.

There is a way out of the ruminating cycles of self-doubt. When the nagging question “Am I good enough?” comes, we can answer, Yes! We are always enough. God has created us that way. We are children of God, equipped with the infinite resources of Soul, forever in the embrace of God’s love and exacting care.

A message of love

A vote for the environment

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow. We’re working on a story about New Hampshire’s annual “ice out,” a sign of spring, and climate change.