- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- US saw biggest spike in gun violence in 50 years. Don’t panic yet.

- Behind stalled bill: Infrastructure is about visions for America

- Can Xi Jinping make China look ‘credible, lovable and respectable’?

- Underground counselors: The chaplains helping transit workers cope

- From coffee to vultures, preserving forgotten species

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

No more sticky stuff? A move to put fairness back on the pitcher’s mound.

Major League Baseball has a sticky fingers problem.

Pitchers are cheating by using sticky stuff – everything from pine tar to high-tech adhesives. The hurlers hide some goo on their hat, their belt, or their glove and get a little on their fingers between pitches. This kind of thing has gone on for decades. But by some estimates, 70% of all pitchers now do it. They have gotten so good at enhancing the spin rate of their fastballs and sliders that strikeouts are at an all-time high. The league batting average is at an all-time low. And batters are crying foul.

“It’s a huge, huge, huge difference,” said Nick Castellanos, one of the best hitters in baseball today, on “The Chris Rose Rotation” podcast. He adds, “I think it just comes down to the league doesn’t care.”

But apparently it does. Team owners decided last week to begin to strictly enforce the rule against sticky stuff, ESPN reports. Pitchers may be checked by umpires as many as 10 times per game.

In recent years, we’ve seen other moves by the league to restore integrity and fairness to the game. In the early 2000s, MLB cracked down on performance-enhancing drugs. In 2020, Red Sox manager Alex Cora was suspended for a year for stealing signals, another practice that had mostly been ignored by officials.

When rules become mere suggestions, the advantage goes to the lawbreakers. It appears players have now successfully demanded that baseball adhere to its own rules.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

The Explainer

US saw biggest spike in gun violence in 50 years. Don’t panic yet.

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution to rising gun violence. But our reporter looks at what lessons from the past might address the current problem.

Last year likely marked America’s largest single-year rise in violent crime in 50 years – sparked by a sharp increase in shootings after the pandemic began.

Amid a national conversation on policing, the surge adds pressure to policymakers at all levels. Experts caution that while law enforcement is a vital part of public safety, police should be one part in a larger package of solutions. There are well-tested methods that decrease violence, but implementing them at scale will require patience, nuance, and a willingness to think past political narratives.

“Community gun violence – which is really what’s driving this trend – is not the intractable challenge that people think it is,” says Thomas Abt of the Council on Criminal Justice. “In fact, we’ve had success in reducing this kind of violence many times and in many places all around the country. The challenge has been sustaining that success.”

The discourse around public safety has largely devolved into a false either-or choice of supporting or opposing the police. But effective policies don’t fit cleanly into left- or right-wing platforms.

“No city in the United States has sustainably reduced violence by exclusively arresting their way out of the problem or by programming their way out of it,” says Mr. Abt. “Everybody has used a combination of strategies.”

US saw biggest spike in gun violence in 50 years. Don’t panic yet.

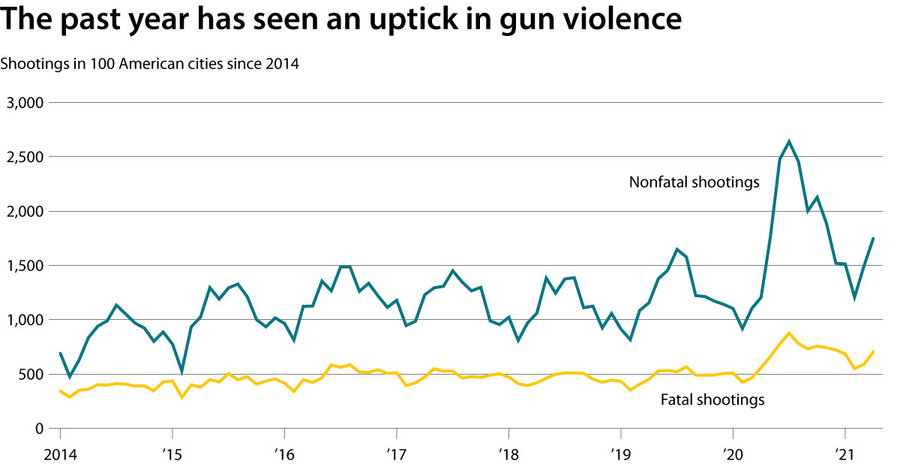

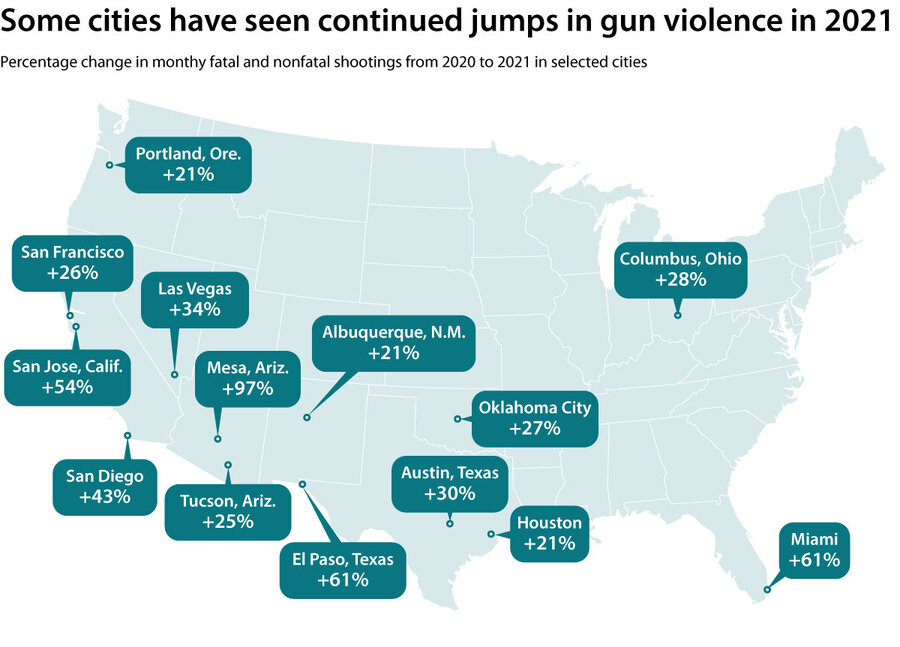

Last year likely marked America’s largest single-year rise in gun violence in 50 years – sparked by a sharp increase in shootings after the pandemic began.

Though the FBI won’t release official numbers until the fall, Patrick Sharkey, a sociologist at Princeton University in New Jersey and an expert on violent crime, estimates the national murder rate rose by 25% to 30%. The rate of nonfatal shootings jumped even more, he says, doubling in many cities.

Amid a national conversation on policing, the surge adds pressure to policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels. Experts caution that while law enforcement is a vital part of public safety, police should be one part in a larger package of solutions. There are well-tested methods that decrease violence, but implementing them at scale will require patience, nuance, and a willingness to think past political narratives.

“Community gun violence – which is really what’s driving this trend – is not the intractable challenge that people think it is,” says Thomas Abt, director of the National Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice at the Council on Criminal Justice. “In fact, we’ve had success in reducing this kind of violence many times and in many places all around the country. The challenge has been sustaining that success.”

Are we seeing a return to 1990s-level violence?

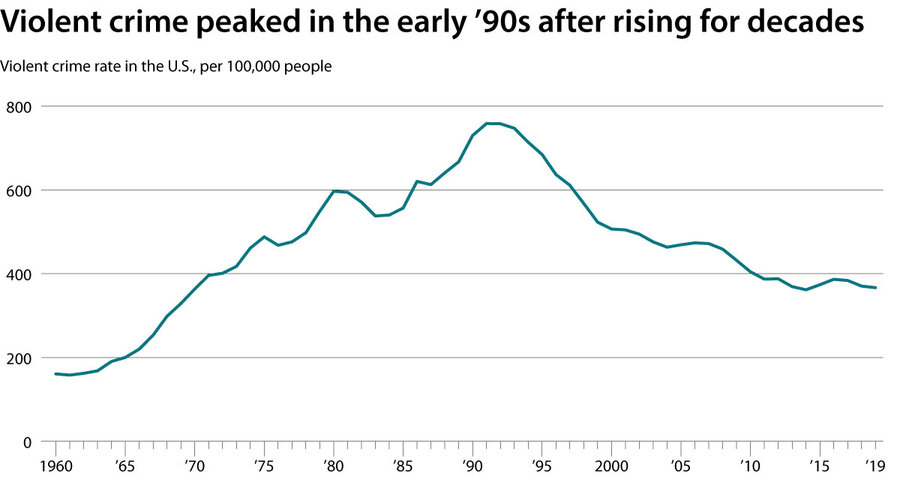

In absolute numbers, the level of gun violence remains far below its peak in the early 1990s – after which shootings plummeted across the United States until 2014, when numbers gradually began ticking up.

According to a report Mr. Abt co-wrote this January, sampling 34 major U.S. cities, the homicide rate in 2020 was 11.4 deaths per 100,000 residents, compared with 19.4 deaths per 100,000 residents in 1995.

FBI Uniform Crime Reports

There’s no universally agreed-upon explanation for the decadeslong drop in violence. Nor is there a clear causal story for the spike last year. Likely at fault, though, are the pandemic and social unrest in response to police brutality.

Institutions like churches, schools, and places of business all help reduce violence by keeping people off the streets and connected to their communities, says Elizabeth Glazer, former director of the New York City Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice. When those structures collapse, “it aggravates the sense of estrangement and inequality and gives rise to the conditions that create violence,” she says.

Citizens who feel alienated from the police, for example, may choose to protect themselves not by contacting law enforcement but by buying a firearm – as Americans have done in record numbers since last year.

“It’s not that a virus causes shootings,” says Jeffrey Butts, director of the Research and Evaluation Center at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York. “It’s that the virus caused the economic disruption and cultural shutdown, which in America resulted in shootings.”

Sharkey, Patrick. AmericanViolence.org, Princeton, N.J.

Will everything go back to normal after the pandemic?

While the pandemic’s severity has waned in the U.S. and last year’s protests have tapered off, a return to the mean isn’t inevitable.

“There were a set of factors that likely came together to create this surge of violence last year, but when those factors go away, it doesn’t necessarily mean that violence will revert back to the level that we were at in 2019,” says Professor Sharkey.

For one, shootings tend to increase in the summer, making an immediate drop unlikely. Violence also tends to build on itself, says Professor Sharkey, meaning every shooting makes another shooting more likely.

The aftermath of last year’s Black Lives Matter protests and defund the police movement also is a complication.

Police have helped keep streets safer, but they come with high fiscal and social costs, says Professor Sharkey. But without comprehensive reform, he says, it can also make cities less safe to have “police stepping back without a set of institutions that can step in.”

Sharkey, Patrick. AmericanViolence.org, Princeton, NJ

What are the solutions?

Most people agree that sustainable progress requires a robust policy response, but consensus ends at the kind of response necessary. The discourse around public safety has largely devolved into a false either-or choice of supporting or opposing the police, says Ms. Glazer. But effective policies don’t fit cleanly into left- or right-wing platforms.

“No city in the United States has sustainably reduced violence by exclusively arresting their way out of the problem or by programming their way out of it,” says Mr. Abt. “Everybody has used a combination of strategies.”

Meanwhile, research shows that things as simple as adding lighting in neighborhoods or helping high school students through algebra are, in the long term, enormously beneficial at reducing violence. Increased opportunities for therapy, work, and tutoring may sound dull, says Ms. Glazer, but they help. Tactics exist that make law enforcement’s work easier and city streets safer.

“We’ve gotten used to kind of equating safety with police and so that’s our first instinct,” says Ms. Glazer. “We really have to begin to have a more integrated strategy of which police are a part.”

FBI Uniform Crime Reports; Sharkey, Patrick. AmericanViolence.org, Princeton, N.J.

Behind stalled bill: Infrastructure is about visions for America

President Biden’s infrastructure proposal redefines the concept, and is infused with values such as racial and economic fairness and stewardship of the planet. Is that visionary or politically a bridge too far?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

America’s roads, dams, freight yards, and so on are getting new attention as Washington wrangles over how to maintain and upgrade facilities vital to the nation. After weeks of trying to negotiate a bipartisan deal with Senate Republicans, the Biden administration on Monday ended the talks.

Underlying that debate is a question of values: What should America look like in 50 years? Should it prioritize economic growth? The environment? Equality of opportunity for racial and ethnic groups or rural versus urban populations?

The Biden administration’s eight-year, $2 trillion American Jobs Plan aims not only to fix roads, ports, and inland waterways but also to battle global warming, modernize child care facilities, raise benefits for home health care workers, boost manufacturing, and secure supply chains – areas traditionally outside the scope of infrastructure. Backers call it visionary. Critics call it an overly expensive big-government wish list.

There are no easy answers. The future of transportation looks especially cloudy at a time of technological and socioeconomic change.

“We’ve never had an infrastructure bill that would be this big and involve this many sectors,” says Kevin DeGood of the Center for American Progress in Washington.

Behind stalled bill: Infrastructure is about visions for America

United States Route 275 has all the signs of a split personality. Running east out of Norfolk, Nebraska, it’s a four-lane divided highway for 12 miles until, inexplicably, it narrows to a two-lane road and makes a long lazy bend southward to Scribner, where it becomes a four-lane again all the way to Omaha.

That 45-mile stretch of unimproved country lane irks Josh Moenning, mayor of Norfolk, a city of 24,000. With a steel manufacturer in town and major cattle-feeding operations in the area, Norfolk sees a lot of truck traffic but has no four-lane access to an interstate or major city. “It’s putting lives in danger,” he says. “And it’s also limiting our community’s ability to grow.”

Detroit has the opposite problem. State and local officials are looking to rip out underutilized I-375 and replace it with a boulevard with green space and bike paths. That could help revitalize largely African American neighborhoods that the interstate destroyed nearly 60 years ago.

America’s roads, bridges, dams, railroads, and so on are getting new attention as Washington wrangles over how to maintain and upgrade facilities vital to the nation. Much of the focus of negotiations between the Biden administration and Senate Republicans has been over how much to spend. Underlying that debate is a question of values: what America should look like in 50 years in terms of concrete and steel, electrical cable and internet fiber. Should it prioritize economic growth? The environment? Equality of opportunity for racial and ethnic groups or for rural versus urban populations?

There are no easy answers. Needs differ by location. States and localities, which own 90% of the nation’s infrastructure and fund 75% of its maintenance and upgrading, will play a large role in deciding where and how the money is spent. The future of transportation looks especially cloudy right now as the U.S. seems poised to make several technological and socioeconomic leaps: from autonomous driving and the electrification of cars to the rise of delivery services and new, post-pandemic work-at-home arrangements.

“Everyone has a different vision for what transportation looks like,” says Bill Eisele, head of the Texas A&M Transportation Institute in College Station. “One thing is fundamentally true: Our transport system is the bedrock of our economy. We have to get people around on our transportation services. We have to get goods and services to those people.”

What the federal government can do with a surge of spending is tilt those decisions in a certain direction. And the Biden administration is tilting hard. In March, it released the American Jobs Plan, an eight-year, $2 trillion proposal to not only fix roads, ports, and inland waterways, but also battle global warming, modernize child care facilities, raise benefits for home health care workers, boost manufacturing, and secure supply chains – areas traditionally outside the scope of infrastructure. Critics call it an overly expensive big-government wish list. Backers call it visionary.

“We’ve never had an infrastructure bill that would be this big and involve this many sectors,” says Kevin DeGood, director of infrastructure policy at the Center for American Progress in Washington. “The Biden American Jobs Plan is a very top-line vision for trying to reorient this broad set of federal expenditures towards [addressing] climate change, equity, [and] inclusive prosperity. But how that actually gets translated into legislation really, really matters.”

Most everyone agrees there’s a problem. After the big interstate- and airport-building era in the last half of the 20th century, the great need today is maintenance. Federal agencies report that more than half of public schools need to be repaired, renovated, or modernized, and nearly 1 in 5 of the nation’s roads are in poor condition. The nation’s 2.2 million miles of underground pipes are so old they average a water main break every two minutes and lose some 6 billion gallons of drinking water every day, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers. Overall, the ASCE gives the nation a C-minus in its latest report, which is actually an improvement, marking the first time in 20 years that the U.S. didn’t earn a grade in the D range.

But much remains to do, the ASCE says. Various estimates put the backlog of maintenance at around $1 trillion.

A vision beyond just repair

Building political enthusiasm around maintenance is never easy, which may explain some of the rationale for the White House pitching its plan as a boost for jobs, green initiatives, and racial equity. “You are not going to attend a ribbon-cutting ceremony for having refurbished something that already exists,” says Ramesh Ponnuru, a conservative columnist and visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, who spoke at an AEI online briefing last week.

For weeks, President Joe Biden and a group of Senate Republicans led by Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia tried to find a bipartisan compromise. The two sides, for example, quickly backed the idea of funding high-speed internet broadband for disadvantaged urban neighborhoods and remote rural communities, where it’s currently not available. But on Monday the president ended those talks because on some issues, notably the taxes to fund the program, the two sides were too far apart.

Now, a bipartisan group of senators is working to craft its own proposal, while congressional Democrats also weigh efforts to pass a bill without Republican votes.

With a razor-thin edge in the Senate, it might prove difficult to pass big spending bills. But what money can’t accomplish, perhaps innovation can.

On the funding side, for example, a change to “design-build-operate-maintain” contracts would require that the state or local government take maintenance costs into consideration on contracts, because the company that builds the project would also have to maintain it. “I call it the quiet revolution,” says Rick Geddes, a visiting scholar at AEI who also spoke at last week’s online briefing.

Era of change in transportation

Experiments are also going on in relieving urban traffic congestion without building more lanes of road. For example, the rise in home-delivery of food and goods means fewer consumers on the road but more delivery vans. Research has shown that half of the trucks making deliveries downtown park in unauthorized spots, clogging driving lanes and causing more congestion. Also, about 80% to 90% of delivery drivers’ time in urban areas is spent on the last 50 feet of a delivery, where drivers on foot are searching for the right address, riding elevators, and so on.

Anne Goodchild, founding director of the Supply Chain Transportation & Logistics Center at the University of Washington, is experimenting with a parking app, common carrier lockers, and microhubs to reduce that time – and thus reduce congestion. Preliminary results suggest the lockers alone could cut drivers’ time in a building by 35% to 75%.

Bigger transportation innovations could also spark changes that would make travel more efficient. “For most of the last 200 years, transportation has changed radically over a period of decades,” says Edward Glaeser, a Harvard economics professor. But from 1970 to 2020, “we really have lived through a remarkably slow period.” Now, high-speed autonomous buses in special lanes might be able to move passengers over medium distances, such as from Chicago to Milwaukee, without all the expense of creating high-speed rail, he adds.

Back in Norfolk, Mayor Moenning banded together with other mayors late last year to push the state for better ways to fund highways. As a result, the state Legislature approved money to turn approximately half of the two-lane U.S. 275 into a four-lane highway.

Additional federal money could mean even more roadwork ahead. “I just hope that at this point we go beyond talking about infrastructure and actually do something,” he says.

Patterns

Can Xi Jinping make China look ‘credible, lovable and respectable’?

As China’s global influence grows, even its leadership recognizes that its aggressiveness, autocratic ways, and lack of transparency, could impede its goals.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

China’s rise on the international stage may be inexorable, but at the moment it seems to be hitting some speed bumps.

To start with, there’s the COVID-19 pandemic, which originated in China. Beijing initially won praise for getting it under control at home quickly and launching an economic recovery. But lately Chinese officials have seemed almost to gloat in their criticism of other countries’ performance, and that has grated.

On top of that, there’s been a lot of talk recently about the possibility that the coronavirus escaped from a Chinese laboratory, rather than jumping from a wild animal to humans. President Joe Biden has even ordered an intelligence review of the evidence for this.

At the same time, Mr. Biden has made China his top foreign policy priority, and he is not shy about criticizing Beijing for its autocratic ways at home and its increasingly assertive military moves in its neighborhood.

That has focused world attention on China, and Chinese leader Xi Jinping has noticed. Last week he told top officials they should project a “credible, lovable and respectable” image of their country.

Given the way the international climate of opinion of China appears to be changing, that could be a tall order.

Can Xi Jinping make China look ‘credible, lovable and respectable’?

China’s inexorable advance on the world stage appears to be hitting some awkward speed bumps.

The Asian giant’s overall direction of travel isn’t in doubt. China has the world’s second-largest economy after the United States and is catching up; Xi Jinping, its most powerful leader since Mao Zedong, remains firmly wedded to a vision of authoritarian rule; and Beijing is pushing ahead with its ambitions for greater military strength and political clout abroad.

But China’s growing power is making a lot of people elsewhere in the world increasingly nervous, and Mr. Xi signaled last week that he understands that. At a Politburo meeting, he urged a shift in the tone of Beijing’s messaging abroad in order to convey an image of China as “credible, lovable and respectable.”

The speed bumps are making that look like a tall order.

First, the coronavirus. Though the pandemic originated in China, Beijing initially earned international kudos for the way it brought COVID-19 under control at home and launched an early economic rebound, while the world’s leading democracies – notably the United States – reacted far less effectively. But the near-gloating tone of China’s criticism of other countries’ response has undermined its position.

And this month, the question of whether the virus may have escaped from a research lab in Wuhan has raised its head again. The idea was once a widely dismissed conspiracy theory that former President Donald Trump weaponized for political purposes. It is now taken seriously enough in Washington that President Joe Biden has ordered a formal intelligence review.

That doesn’t mean the hypothesis will prove true: Many scientists still believe it’s more likely that the pandemic resulted from animal-to-human transmission of COVID-19. Yet the review has drawn new attention to the Chinese authorities’ ambiguity about the origins of the virus, and revived international criticism of its habitual secrecy.

Such criticism is spreading, too, with regard to China’s oppression of the Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang, in the northwest of the country, and its crackdown on pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong. Enter speed bump number two: greater international uneasiness over China’s domestic autocracy and its growing assertiveness overseas.

The arrival of a new administration in Washington has been critical to this trend. President Biden has made China and the Asia-Pacific region the main focus of his foreign policy, a focus evident even this week as he set off for a series of summits with allies in Europe and a meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

In an op-ed piece in The Washington Post before leaving, he framed the trip as part of a wider struggle between democracy and autocracy, stressing the need to “confront the harmful activities” not just of Russia, but of China too.

In talks with European leaders, Mr. Biden said he would “focus on ensuring that market democracies, not China or anyone else, write the 21st-century rules around trade and technology.”

And he pledged to lead U.S. allies in a challenge to China’s international influence, promising that “the world’s major democracies will be offering a high-standard alternative to China for upgrading physical, digital and health infrastructure” around the world.

Mr. Biden has already begun redirecting military spending with a view to shoring up defense preparedness with allies in the Asia Pacific region. That is designed to deter a further Chinese buildup in disputed areas of the South China Sea and, above all, any military move against Taiwan, the island state Mr. Xi has vowed to reunify with the mainland.

None of this is likely to have an immediate effect on China. A new infrastructure drive by the world’s major democracies, even if it succeeds, will take time. The new seriousness of purpose in Washington, however, was underscored this week with rare bipartisan backing in the U.S. Senate for a $250 billion package to promote high-tech innovation and production in the U.S. Its explicit aim: to fend off competition from, and dependence on, China.

China’s economic weight, and its importance as a trade partner and consumer market, still lend it political and diplomatic influence. That’s true even in some of the European countries whose leaders Mr. Biden is meeting this week, such as Germany and Italy.

It is even more relevant for Asian allies. Australia and New Zealand, for instance, depend on China as a key export market. Australia has been caught in a punishing trade war with Beijing since publicly calling earlier this year for an independent inquiry into the origins of the pandemic, and sharply criticizing China’s crackdown in Xinjiang and Hong Kong.

New Zealand has so far escaped Chinese trade retaliation by treading more softly. Though critical of the treatment of the Uyghurs, it has avoided using the term “genocide” and declined to join the U.S., Britain, the European Union, and Canada in imposing sanctions.

Yet last month, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern remarked that differences with China were getting “harder to reconcile.”

And when she welcomed Australia’s Scott Morrison for their first face-to-face talks since the pandemic, the two leaders issued a joint statement voicing “grave concerns about the human rights situation in Xinjiang” and the limits on “the rights and freedoms of the people of Hong Kong.”

Prime Minister Morrison cautioned “those far from here who would seek to divide us.” He couldn’t have been clearer about who he meant if he’d said it in Chinese.

A deeper look

Underground counselors: The chaplains helping transit workers cope

Attendance in U.S. houses of worship is down, but our reporter finds the use of chaplains in workplaces is rising. Employers, including the New York City transit system, see spiritual care as crucial to their employees’ well-being.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

-

By Diana Kruzman Correspondent

What does a chaplain have to offer a subway driver?

A lot, it turns out.

Chaplains with New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority are there for subway operators at their worst moments, like when someone falls or jumps in front of a moving train. But they also fill other gaps that mental health services and other employee assistance programs may not always be able to reach. They aid not just subway operators, but also transit workers across the system who have to shoulder the burdens of mental illness, poverty, and resentment that affect millions of riders. The chaplains have become de facto therapists and counselors, shepherding employees through everything from traumatic experiences at work to family problems at home.

All of this comes as religious observance is declining in the United States. Yet these chaplains find success with MTA workers of all faiths, as well as those without one.

“We actually see this as an important, if not clarion, call to chaplaincy to step into the gap, simply because people may not be affiliating with congregations, but they still have spiritual needs,” says Trace Haythorn, executive director of the Association for Clinical Pastoral Education. “And they’re looking for ways to get those addressed.”

“The gift of chaplaincy practice,” Dr. Haythorn says, “is presence.”

Underground counselors: The chaplains helping transit workers cope

By the time the Rev. Kelmy Rodriquez became a chaplain, he knew what it meant to want someone who would listen.

At the age of 8, he lost his mother to gun violence. When he was 22, his wife, who was pregnant, was killed in a drive-by shooting. He struggled with drug use and homelessness, as well as a loss of faith, until a religious experience more than two decades ago changed his trajectory.

For more than 10 years, Mr. Rodriquez worked as an emergency medical technician, where he saved lives but also was troubled by the deaths he couldn’t stop. In 2015, he graduated from seminary school, compelled to prevent some of the suffering he had witnessed.

This personal mission has led him to an unlikely place – the labyrinth of tunnels that make up New York City’s sprawling subway system. Mr. Rodriquez started volunteering as a chaplain with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) in 2019.

Chaplains typically provide religious services for firefighters, soldiers, hospital staff, and prison inmates – populations with high rates of trauma, stress, and burnout. But Mr. Rodriquez saw a need for spiritual and emotional support among transit workers, and the agency was in the midst of expanding its chaplain force. Since then, he’s counseled workers going through financial difficulties, attended wakes and funerals, visited people in the hospital, and showed up at the scene of train collisions.

“I made a deal many years ago,” says Mr. Rodriquez, “and I’m keeping up my end of the bargain. ... If I can make a difference in someone’s personal life, I’m happy.”

New York’s transit chaplain program underscores the growth of spiritual counseling in workplaces across the country. Though church attendance and mainstream religion may be declining in the U.S., the use of chaplains is becoming more common as employers increasingly see spiritual care as a crucial part of employee well-being, experts say.

At the MTA, chaplains fill a gap that mental health services and other employee assistance programs may not always be able to reach. They aid workers who have to shoulder the burdens of mental illness, poverty, and resentment that affect millions of the system’s riders. The chaplains have become de facto therapists and counselors, shepherding employees through everything from traumatic experiences at work to family problems at home.

“The MTA really wants to invest in the employees and their families,” says George Anastasiou, the agency’s chief chaplain.

Consulting with a chaplain, he notes, is often the best way for them “to deal with getting through their grief, a death of a loved one, or a traumatic experience that they witnessed at work. So there is a great number of employees that seek solace and comfort in their time of pain.”

With COVID-19 still affecting many in New York City, the MTA’s chaplains face the added burden of helping transit workers process the loss of their colleagues, family, and friends, and cope with other disruptions caused by the pandemic. The coronavirus has so far killed more than 160 transit employees, and plunging ridership has led to a budget crisis that threatens much-needed jobs.

Mr. Rodriquez recalls speaking to a station agent whose aunt had just died of COVID-19 and who was struggling to deal with the pain. He told her that he understood, that he too had lost someone, but that focusing on the good memories would help keep that person alive in her heart. For the first time since the start of their conversation, he saw her smile.

“I will not lie, she did cry in the booth,” Mr. Rodriquez says. “She actually exited the booth with her mask on and hugged me and cried in my arms. And I gave her my number; I said I’m always available.”

The roots of chaplaincy in the U.S. date back to the Revolutionary War, when military chaplains accompanied soldiers fighting against the British. But over time, workplaces began to employ chaplains as well. They roamed factories during the Industrial Revolution. High-stress occupations such as policing and firefighting have used them since the early 20th century. The idea of a transit chaplain, though, is relatively recent and in the U.S. remains rare. New York and other transit agencies, such as in the San Francisco Bay Area, use chaplains to aid transit police but the MTA corps is unique in counseling bus and subway workers.

The MTA got its first chaplain in 1985. That year, Rabbi Harry Berkowitz founded the program after spending seven years as a volunteer chaplain with the New York City Transit Police – patrolling the subways with transit officers, earning their trust, and helping build morale in an agency that was often seen as a lesser version of the New York Police Department. When David Gunn, then the president of the New York City Transit Authority and lead architect of the subway’s renaissance after the turbulent 1970s, asked Mr. Berkowitz to expand his duties to cover all MTA employees, the rabbi took up the cause.

“My goal was to make everybody feel like a family, regardless of what level or position you were in,” says the bearded Mr. Berkowitz, who grew up in Sheepshead Bay, a neighborhood in the New York borough of Brooklyn. “No issue was off the table – you could say anything that was on your mind.”

Over the next few years, Mr. Berkowitz visited every transit district in the city, established a medical rescue unit within the chaplaincy, and printed brochures promoting the program to distribute among MTA employees. He also prepared the organization to respond to any crisis – a mission that was tested after 9/11, when chaplains from around New York City and the tri-state area responded to ground zero and counseled first responders.

One of these was Sister Maureen Skelly, a nun and former volunteer transit police chaplain who retired in 2007 after 25 years with the MTA. At the time of the attacks, she was working at a Jesuit retreat on New York’s Staten Island, where police, firefighters, and anyone else who had to do the difficult work of sifting through debris and searching for bodies showed up for a hot meal and, increasingly, spiritual guidance. Transit workers, too, were among them – as many as 4,000 MTA employees spent time at the site where the towers fell, searching for survivors and removing debris. Some then went back to their regular jobs keeping the city’s transit system moving.

“You couldn’t imagine it if you tried,” says Ms. Skelly, referring to the months she spent counseling workers at the Jesuit retreat, Mount Manresa. “When you saw the looks on their faces, the tiredness of them, you saw them trying to get on the bus and they just wanted to get off the bus and go home. But they couldn’t.”

Many were also dealing with personal loss – 150 family members of MTA employees were killed, according to Mr. Berkowitz. “They cried, they got mad,” says Ms. Skelly. “It took a long time to want to go on a bus again. But little by little they came back to themselves.”

Mr. Berkowitz was hired full time by the MTA in 1993 and served as the transit system’s chief chaplain until he retired in 2019, leaving the role to Mr. Anastasiou, a Greek Orthodox priest and former transit police chaplain. But over three decades at the agency, Mr. Berkowitz aimed to build up a roster of chaplains to cover as much of the city as possible, which is how he came to recruit the Rev. Michael Gelfant, a priest at Blessed Trinity Catholic Parish in southern Queens.

In 2010, Mr. Gelfant, who was then at a parish in southern Brooklyn, got a call from Mr. Berkowitz. He asked if Mr. Gelfant was interested in becoming a chaplain with the MTA. When the priest said no, the rabbi kept calling, until Mr. Gelfant finally relented. “He said, ‘We won’t call you too often.’ That was in October,” Mr. Gelfant says. In November, suicides on the tracks started to rise, as they tend to do each winter, and Mr. Gelfant was out on a call almost every night.

Like other volunteer chaplains who form a “rapid response team” for the MTA, Mr. Gelfant was on duty 24 hours a day, seven days a week, he recalls in a 2019 interview. He could get a text or a call at any hour, mostly from Brooklyn but also from Staten Island, Queens, the Bronx, or even Long Island. He usually entered a situation knowing little more than a location and a basic description – train derailment, attack on a conductor, death on the tracks.

“I was a little apprehensive at the beginning, but seeing – I don’t want to say the success of it, because there really is no success in any of this – but maybe the fruit of the labor at the moment of trauma and need makes it worth getting up and going in a split second or in the middle of the night,” Mr. Gelfant says. “So that’s why I keep doing it.”

Sometimes he had to rush straight to a hospital if a bus or train operator was injured on the job. He recalls one train conductor who was sprayed with bleach, and a bus operator who was stabbed with a hypodermic needle. Twice he had to minister to employees whose co-workers had been hit by trains. Illnesses and accidents, such as someone falling down the stairs, were his territory, too.

At such scenes, Mr. Gelfant headed for the crew first. He checked whether they needed medical attention and prayed with them if they requested it. He would give a blessing to a passenger or bystander if he was asked to – most people recognized him as a Roman Catholic priest by his vestments – but says he wasn’t there to proselytize or lead mass prayer sessions. He tried not to get in the way of the police or firefighters while also making sure the train operators knew he was available if needed.

“Sometimes [the operators are] strong – they’ll say ‘I’m all right,’ but in private they’ll break down,” Mr. Gelfant says. “No one is ever all right.”

Later, many train operators would confess their feelings of guilt and helplessness, their conviction that they should have acted faster or done more to stop the train in time. Mr. Gelfant tried to talk them through those thoughts and come to terms with what happened.

“Trains don’t stop at the drop of a dime; there’s nothing you can do,” he says. “You hit the emergency brake and that’s it. But they still believe that they killed someone, that they murdered someone. ... And that’s when we have to say, ‘No, let me help you rephrase that.’”

Today, the MTA has 68 volunteer chaplains and several full-time paid administrators, who help organize counseling sessions and send out requests when chaplains are needed at the site of an emergency. Human-train collisions, referred to in transit parlance as a “12-9,” happen frequently. In 2020, the MTA recorded 169 of them, about a third of which were fatal.

But the chaplains also visit hospitals, offer marriage or grief counseling, say prayers at graduations, and perform religious services at wakes, funerals, baptisms, weddings, and bar mitzvahs. MTA workers and their family members can request to talk to a chaplain of any faith, and the chaplains also walk through subway stations and bus depots, checking in with workers and letting them know there’s someone to talk to.

Sometimes, workers don’t want to talk about a specific traumatic experience but simply about the challenges they face on the job. A 2005 report from the New York Committee for Occupational Safety and Health found that city transit workers were sometimes attacked by disgruntled passengers and faced constant pressure to adhere to schedules. They reported being exposed to toxic substances, getting lost in subway tunnels, and seeing co-workers shot to death.

But the traumas that chaplains respond to don’t always have to be work-related. They also counsel employees through family adversity, accompanying police, for instance, during death notifications or personally reaching out to family members if an MTA employee has been killed.

When Rosetta Simmons’ husband, a train conductor, died by suicide in June 2001, Mr. Berkowitz showed up at her door in East Harlem. Ms. Simmons, who at the time worked as a train operator for the MTA, says it didn’t matter that she was a Baptist and Mr. Berkowitz was Jewish – he talked to her about her feelings, not about her faith.

The visit was unexpected, she says, but it provided much-needed comfort at a time when she was going through her own struggles with mental health.

“It showed that they really care,” Ms. Simmons says. “Because most of the time, you know, you feel you’re just a number.”

For much of American history, the institution of chaplaincy remained rooted in Christianity, and specifically Protestantism. But as American religious demographics have changed, so have chaplains, who now focus less on approaching someone from the viewpoint of their particular faith and more on listening to people’s problems and offering general spiritual guidance.

In many cases, the experience of talking to a chaplain doesn’t have to be overtly religious at all, and chaplains are taught to “be present without proselytizing,” says Trace Haythorn, executive director of the Association for Clinical Pastoral Education, which provides training and certification programs for chaplains.

The results of a Gallup survey released in March show that less than half of American adults belonged to a religious congregation in 2020, compared with 70% in 1999. At the same time, the proportion of Americans identifying as “spiritual but not religious” has grown, Dr. Haythorn says. “We actually see this as an important, if not clarion, call to chaplaincy to step into the gap, simply because people may not be affiliating with congregations, but they still have spiritual needs,” Dr. Haythorn says. “And they’re looking for ways to get those addressed.”

Chaplains often come into contact with people who may have mental illness, which requires them to determine how much they can do and how much should be left up to licensed practitioners. Chaplains work in concert with other professionals assisting employees who are going through a difficult time, including at the MTA, which offers mental health counseling and referral services to all employees.

But chaplains may be better equipped to respond in the event of a crisis or address an urgent need, while also serving as a bridge to other services, Dr. Haythorn says. Many are trained in clinical pastoral education, a program that teaches chaplains how to take a holistic approach to health care that incorporates physical, mental, and spiritual elements.

“When chaplains are doing their work, the person in front of them is the center of their attention. And that person recognizes them as such, so that they really feel that they are being emotionally, spiritually held in that moment,” he says. “In a setting like public transit, they are introducing people to the resources that are available to them, and being able to provide that kind of confidential support so that the employee knows that they’ve got an ally within the system.”

The chaplains’ counseling skills have become all the more important during the COVID-19 pandemic, as transit workers have faced personal losses as well as professional difficulties. The Transportation Research Board, a division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, is in the planning stages of a study to measure the “mental health implications of the stress of exposure, illness, and potential death” from the virus on public transit workers, who in most cases were classified as essential workers who could not stay home.

Dr. Haythorn says that pandemic-related budget cuts to service have also upset riders, who can take their frustration out on employees. Mr. Rodriquez, for one, has seen his call requests from concerned and grieving transit workers triple in number since the start of the pandemic.

Sometimes the chaplains will offer support even if they aren’t summoned. In September 2014, Igor Kruglyak’s father died, and three chaplains from the MTA came to the funeral unexpectedly. Mr. Kruglyak, who has done electromechanical maintenance for the MTA since 2007, says the chaplains gave him a card and let him know he could call them at any time. Later, when Mr. Kruglyak, who is Jewish, wanted to take a day off to observe Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year in Judaism, he called the chaplain’s office to help negotiate with a supervisor who was trying to get him to come in to work. Throughout both events, he says, he was grateful for the emotional support that the chaplains provided.

“I didn’t ask for financial support, I’m not asking for anything, but it was very emotional. It was very helpful,” Mr. Kruglyak says. “These people never saw me, they never talked to me. And they showed up at the funeral.”

For many transit workers, even if they don’t end up discussing their emotions, spirituality, or religion, just having someone there makes a difference.

“The gift of chaplaincy practice,” Dr. Haythorn says, “is presence.”

Points of Progress

From coffee to vultures, preserving forgotten species

This week’s progress roundup includes scientific breakthroughs in turning discarded plastic into jet fuel, a more climate-resilient coffee bean, and a milestone in high-intensity lasers.

From coffee to vultures, preserving forgotten species

Breakthroughs this week include physicists who achieved the highest intensity laser ever, and chemical engineers who catalyzed jet fuel from plastic waste.

1. United States

Researchers from Washington State University have developed a cost-effective process to convert plastic into jet fuel, paving the way for large-scale chemical recycling. Plastic pollution is a growing problem, but recycling initiatives are often stymied by a lack of financial incentives. Most mechanically recycled plastics are melted down and reshaped into a new product, with some degradation in quality. Chemical recycling creates higher-quality products, but has been too expensive and time-consuming to bring to scale.

In the journal Chem Catalysis, the WSU team explains that it was able to turn 90% of polyethylene into jet fuel at a relatively low 428 degrees Fahrenheit, within 60 minutes. The method, scientists say, is designed to upcycle the plastic causing the most pollution and to model financially viable recycling technology. They’re now working to scale the catalytic process and experiment with other types of plastic waste.

Interesting Engineering

2. Galápagos Islands

A coalition of more than 40 organizations is putting $43 million toward restoring Galapágos island habitats. Ecuador’s famous archipelago is a biodiversity hot spot, known for its many endemic species. The initiative’s priorities are reversing degradation on Floreana Island, as well as protecting the area’s marine reserves and helping boost populations of the critically endangered pink land iguana. Partners include local governments, nongovernmental organizations, and others. One of the effort leaders, a global ecosystem restoration group recently rebranded as Re:wild, is backed by actor and environmentalist Leonardo DiCaprio.

“Time is running out for so many species, especially on islands where their small populations are vulnerable and threatened,” said Paula A. Castaño, a veterinarian and island restoration specialist living on the Galapágos. “We know how to prevent these extinctions and restore functional and thriving ecosystems – we have done it – but we need to replicate these successes, innovate and go to scale.”

Mongabay

3. Sierra Leone

The rediscovery of a long-lost, heat-resistant coffee species is offering hope for an industry struggling with the effects of climate change. Not seen in the wild since the 1980s, Coffea stenophylla has demonstrated a high heat tolerance and strong flavor profile, similar to standard-bearing arabica, which makes up 56% of global coffee production. (Robusta, a cheaper species largely used in instant coffee, represents 43%.) A group of scientists led by botanist Aaron Davis located a healthy population of C. stenophylla in southeastern Sierra Leone in 2018, and recently confirmed its viability as a hearty arabica alternative in a study published by Nature Plants.

Alternatives like this are needed – some researchers expect global arabica production to fall 50% over the next few decades due to climate change. “Stenophylla provides us with an important resource for breeding a new generation of climate-resilient coffee crop plants,” said Dr. Davis.

Reuters, Nature Plants

4. Bulgaria

Bulgaria now has a stable population of around 80 griffon vultures, more than four decades after the birds were considered extinct in the Balkan nation. Among the population are roughly 23 to 25 breeding pairs, according to a new report. Scavenger species play a critical role in maintaining healthy ecosystems, but the griffon vulture was considered missing from Bulgaria until 1978, when scientists discovered a colony in the Eastern Rhodopes Mountains.

Now, after a decadelong restoration effort by the Fund for Wild Flora and Fauna, Green Balkans, and the Birds of Prey Protection Society, they’re reclaiming their historical breeding range. It’s not an entirely smooth transition, say researchers, with about a third of one site’s released vultures getting electrocuted by nearby power lines. Still, other signs show the species is adjusting well – 80% are relying on animal carcasses found in the field, rather than on conservationist-operated feeding stations, and vultures have been reproducing in the wild since 2016. The griffon vultures’ continued success in the region also offers hope for the cinereous and bearded vultures, both of which are native to Bulgaria but are now found only in Asia.

Earther, Biodiversity Data Journal

5. South Korea

A research team at the Institute for Basic Science in Seoul has created the world’s highest-intensity laser, opening up new opportunities to understand the cosmos. Intensity depends on two factors: high power output, focused onto a tiny space. At 1023 watts per centimeters squared, IBS physicists have achieved the equivalent of directing all the Earth’s sunlight onto an area many times smaller than the diameter of a human hair.The previous record, set by scientists from the University of Michigan in 2004, was 1022 W/cm2.

The research team used a set of deformable mirrors – similar to those used in astronomy – and a large off-axis parabolic mirror to fine-tune their pulsed laser system. “With the highest laser intensity achieved ever, we can tackle new challenging areas of experimental science,” said Nam Chang-hee, director of the Center for Relativistic Laser Science and leader of the study. “This kind of research is directly related to various astrophysical phenomena occurring in the universe and can help us to further expand our knowledge horizon.”

Aju Business Daily, Cosmos

World

A startup is using wood waste to 3D-print architectural accents and consumer goods that mimic the properties of natural wood. Wood manufacturers generate millions of tons of sawdust each year, much of which is burned or landfilled. Forust’s technology deposits a binding agent made with lignin – the organic polymer byproduct of the paper industry – over thin layers of sawdust to create intricate designs, one layer at a time.

Unlike particle board, another wood substitute that uses sawdust, Forust’s pieces print a realistic grain running throughout, so they can be sanded and stained like natural wood. This also makes 3D-printed wood a possible alternative for the luxury trade, which has made some highly trafficked tree species vulnerable to overexploitation. Forust is currently working on its first collection with designer Yves Béhar’s Fuseproject.

Fast Company, 3D Printing Media Network

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Mexicans save their democracy

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

On her first trip to Central America to promote good governance, U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris found a pleasant surprise in one stop. Despite a wave of campaign violence, Mexican voters turned out strong on June 6 for the country’s largest, and perhaps cleanest, elections.

They also sent a message to a populist president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, that he should not jeopardize the independence of the election watchdog and the courts. His Morena party lost dozens of seats in Congress, dashing hopes of a supramajority that would allow him to alter the constitution.

For a democracy that ended one-party rule only a quarter-century ago, Mexico now emerges as a potential model for a region backsliding in electoral integrity and toward strongman rule. A whole range of civic-minded people, from a million poll workers to public intellectuals, stood up for the endurance of Mexico’s democratic institutions.

Mexico’s recent history of both left and right governments has led many voters to worry first about their country’s ability to find centrist solutions. Their display of self-governance should make the Biden administration’s goal of seeing and supporting real democracy in Central America a bit easier.

Mexicans save their democracy

On her first trip to Central America to promote good governance, U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris found a pleasant surprise in one stop. Despite a wave of campaign violence, Mexican voters turned out strong on June 6 for the country’s largest, and perhaps cleanest, elections.

They also sent a message to a populist president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, that he should not jeopardize the independence of the election watchdog and the courts. His Morena party lost dozens of seats in Congress, dashing hopes of a supramajority that would allow him to alter the constitution.

For a democracy that ended one-party rule only a quarter-century ago, Mexico now emerges as a potential model for a region backsliding in electoral integrity and toward strong-man rule. A whole range of civic-minded people, from a million poll workers to public intellectuals, stood up for the endurance of Mexico’s democratic institutions. They affirmed the need for a check on the executive branch and a higher level of debate and consensus.

The educated middle class in Mexico City, where the president was once a popular mayor, was especially important in giving AMLO, as the president is called, an electoral shellacking. While his party retains a majority in Congress and took most of the governorships on the ballot, he appeared humbled after the election. His ambitions to rule without the restraints of normal democracy were given a course correction by voters eager to safeguard basic institutions.

The results are notable for a country that has the ninth highest homicide rate in the world and whose economy has not grown in two years. Mexico’s recent history of both left and right governments has led many voters to worry first about their democracy’s ability to find centrist solutions. Their display of self-governance should make the Biden administration’s goal of seeing and supporting real democracy in Central America a bit easier.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Stomach problems healed after finding Christian Science

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Laraine Mercia Matingou Samba

Frequently bedridden and unable to attend school due to various ailments, a young woman yearned for healing. That’s when her family learned about Christian Science – and it turned the situation around completely.

Stomach problems healed after finding Christian Science

I became acquainted with Christian Science nearly a decade ago when I was very sickly, suffering from a stomach ulcer, stomach pains, and other ailments. I had been striving to earn my primary school certificate, but I had given up hope because I spent most of my time in bed. One day, my father was listening to Radio Congo, as he often did, hoping to find a broadcast on health so that he could learn about new things to try to help me.

That afternoon, when he turned on the radio, he tuned directly to a Christian Science broadcast. During the program the presenter shared that he had not taken any medicine for several years, because he found healing in the one true Mind, God.

This was a revolutionary idea to my father, and he wanted to know more. He called the number provided on the broadcast to find out more about Christian Science, and he learned that there were some branch Churches of Christ, Scientist, close to us. He also learned about Christian Science practitioners, people who dedicate their time to praying for those in situations such as mine.

Because of my ailments, I was unable to leave the house, but my dad and one of my brothers went to one of the churches. When they arrived, someone there recognized my father, who had been his teacher in school. He introduced my father to a practitioner, who talked with them further about Christian Science and gave them a copy of The Herald of Christian Science, which had testimonies from people who had been healed of stomach ulcers.

I read the Herald, which gave me encouragement that I too could be healed, and I did not hesitate to pursue Christian Science treatment. I contacted the practitioner, who shared with me citations from the Bible and the Christian Science textbook, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy. At first, I felt reading all these passages was boring. But as the days went by, things changed.

I really loved this passage from the Bible: “Because thou hast made the Lord, which is my refuge, even the most High, thy habitation; there shall no evil befall thee, neither shall any plague come nigh thy dwelling” (Psalms 91:9, 10). This helped me see that no sickness, no bad thoughts, no aggressive suggestions that I was vulnerable, could invade my true consciousness to frighten and discourage me. God, the one true Mind, was there to protect and sustain me at every moment.

Little by little my unhealthy appearance changed to that of a strong and healthy person. By the end of a few weeks I was feeling extremely well, and the ailments did not return.

It was then that I, along with my parents and two of my brothers, began attending the Christian Science church. At first I was not very enthusiastic, despite my healing, but over time I came to love what I was learning in Sunday School: that we can turn completely to God for solutions to all problems, that God loves us all, that He does not choose some to bless and others not to bless as I had believed before. God is always sustaining us, there to guide our steps, and we can trust in God with all our heart.

As for my studies, I was reassured by the idea that God’s children are governed by God, who knows no failure, and therefore man cannot fail either. Holding to this spiritual truth, ultimately I did get my diploma, which allowed me to go on to high school.

Since these events I’ve also had the privilege of taking Christian Science Primary class instruction, which has empowered my study and practice of Christian Science.

I am sincerely grateful to our Father-Mother, God; to Christ Jesus; and to Mary Baker Eddy, who discerned the Science behind Jesus’ ministry and left it for the world.

Adapted from an article published on the website of The Herald of Christian Science, French Edition, Aug. 31, 2020.

Looking for more timely inspiration like this? Check out the “Related stories” below; explore other recent content from the Monitor’s daily Christian Science Perspective column; or sign up for the free weekly newsletters for this column or the Christian Science Sentinel, a sister publication of the Monitor.

A message of love

A new window on Paris

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow. We’re working on a story about a new art exhibit that takes a less-traditional approach to a day at the American beach.

Finally, we invite you to meet the humanitarians solving community problems. Meet your fellow Monitor subscribers. Join the conversations at Community Connect. On this page, you can see panel discussions, Q&A interviews, and audio reporter profiles – all are included in your subscription. It’s our way of connecting you with the work of good Samaritans in the world.