- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- The ‘big lie,’ loyalty to Trump – and the defense of democracy

- Virginia governor’s race: What does ‘pro-business’ mean in a pandemic?

- How Chattanooga is working to right the wrongs of urban renewal

- Taking better care of people: Silver Alerts, non-English driver’s tests

- They found hope in Afghanistan. Now they strive to preserve it.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Can a philosophy of progress make more possible?

Last month, Jason Crawford launched a nonprofit to study something we often take for granted: progress.

“We wake up in the morning on a soft mattress,” says Mr. Crawford. “We go take a shower under hot running water. We pull fresh milk, eggs, and orange juice from the refrigerator. We commute to work on a train or in a car. We take the elevator up to a high-rise where we sit in a comfortable, air-conditioned office next to plate-glass windows and earn a living by typing on a computer. And we forget that, just 100 years ago, people could not do many of those things.”

Mr. Crawford founded The Roots of Progress to establish a philosophy of progress. Why is it that some civilizations, locales, and institutions flourish, while others stagnate? His theory posits if research can pinpoint how human advancement occurs, we may be better able to replicate the conditions and qualities that make it possible.

It’s more than just an arcane academic pursuit, says the Silicon Valley software engineer. He believes that societal fears of fresh endeavors – often rooted in exacerbated fears of risks that don’t account for reasonable trade-offs – can stall progress.

To counter that, the nonprofit’s founder wants to acknowledge problems with technological advancement and what we can learn from those instances, but also tell stirring stories that illustrate the history of breakthroughs. The Roots of Progress aims to offer a vision of the possibilities for solving problems such as poverty, climate change, pollution, job loss, and pandemics.

“The most important goal of this new organization,” says Mr. Crawford, “is to make sure that the next generation of scientists, engineers, and startup founders is inspired and motivated to continue moving the world forward.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

The ‘big lie,’ loyalty to Trump – and the defense of democracy

What does it mean to be a Republican, post-Trump? Less than a year after 2020, a poll finds that claiming the election was stolen is now a defining characteristic.

-

Dwight Weingarten Staff writer

The “big lie” may be getting bigger.

With former President Donald Trump pushing down from the top, and voters from his base pushing up from their states and local areas, the stolen-election falsehood has spread beyond the presidential level into lower political contests.

- In California, Trump-backing talk show host Larry Elder posted a “Stop Fraud” page on his campaign website where voters could post affidavits of suspicious activity prior to the Sept. 14 recall, won handily by Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom.

- In Nevada, Senate candidate Adam Laxalt – whose father and grandfather were senators – has talked about mounting preemptive legal challenges, 13 months prior to elections.

- In Pennsylvania, gubernatorial candidate Lou Barletta wrote that “we’ve always known that dead people have voted in Pennsylvania elections, but recently we’ve made it so they don’t even have to leave the cemetery to do so.”

The bottom line is that false fraud charges have sown real mistrust about U.S. elections – and further polarized an already divided country. Going forward, it seems likely that the battle for more political offices won’t end on Election Day.

“We’re entering a period in which what were once nonpartisan and widely accepted means for determining election outcomes are now becoming partisan and contested,” says David Hopkins, a political scientist at Boston College.

The ‘big lie,’ loyalty to Trump – and the defense of democracy

The “big lie” may be getting bigger.

Former President Donald Trump has long claimed without evidence that Democrats stole the 2020 election, a falsehood that his opponents have dubbed the “big lie.” At a rally in Georgia last week, Mr. Trump expanded this claim to hint – also without evidence – that former President Barack Obama actually lost his reelection race in 2012.

“Nowadays with these elections, who knows if he won?” said Mr. Trump to the roars of supporters gathered at the Georgia National Fairgrounds in Perry.

It has been almost 11 months since last November’s presidential vote. Since then, Mr. Trump has worked hard to broaden and deepen the reach of his false election night statement that “frankly, we did win this election.”

He has continued to push for reexamination of the votes in key states, despite the recent “forensic audit” in Arizona’s Maricopa County, increasing President Joe Biden’s winning margin. In many states, he is pushing preferred candidates for secretary of state, a post that oversees elections.

Meanwhile, Republicans throughout the country are embracing unfounded and vague allegations of fraud in their own elections, spreading the “big lie” down ballot. In the California recall election earlier this month, for instance, GOP candidate Larry Elder said of Democrats, “They’re going to cheat. We know that,” prior to Gov. Gavin Newsom’s historic margin of victory.

The bottom line is that false fraud charges have sown real mistrust about U.S. elections – and further polarized an already divided country. Going forward, it seems likely that the battle for more and more political offices won’t end on Election Day.

“We’re entering a period in which what were once nonpartisan and widely accepted means for determining election outcomes are now becoming partisan and contested,” says David Hopkins, an associate professor of political science at Boston College.

The Eastman memo

Mr. Trump’s Georgia rally is not the only event that has raised the salience of the false stolen-election claim in recent days. The release of “Peril,” the new book on the last days of the Trump administration by Washington Post journalists Bob Woodward and Robert Costa, revealed that prominent conservative lawyer John Eastman gave then-Vice President Mike Pence a six-step memo for overturning the election during the counting of electoral votes on Jan. 6.

Mr. Pence declined to go along with the scheme, as advisers warned him it was outside his constitutional authority. Mr. Trump, the book reported, was furious about Mr. Pence’s demurral.

In addition, last week the Republican-led effort to reexamine the vote in Arizona’s Maricopa County released its long-awaited final report. Mr. Trump and his allies have long said this “audit” would unearth “thousands and thousands” of fake Biden votes. Instead, it produced a final tally that widened Mr. Biden’s victory in the state by a few hundred ballots.

Trump backers pointed to the report’s claim that tens of thousands of ballots might be in question due to various alleged problems, such as the fact that a substantial number of mail-in ballots came from voters listed under prior addresses.

But Maricopa County officials disputed these claims, saying they largely reflected flawed methodology or a misunderstanding of election laws. The company hired to conduct the partisan review, Cyber Ninjas, had no background or training in election recounts. The report itself was careful to note that there could be legal explanations for all the noted discrepancies – and that disputed votes were almost equally balanced between Republican and Democratic voters, meaning neither side would benefit even if they were thrown out.

Yet Mr. Trump and his allies continue to claim the Maricopa effort as a big win, despite its actual findings. And if anything, his effort to push similar reexaminations is gaining momentum in many states. A similar study is well underway in Wisconsin. In Pennsylvania, Republican state senators have voted to subpoena vote records and nonpublic personal information from up to 9 million registered voters.

For Republican political candidates across the country, subscribing to aspects of Mr. Trump’s false stolen-election claim has become an important litmus test. Many grassroots GOP voters demand it. A recent CNN poll found that 78% of Republicans do not believe that Mr. Biden won the election. And 54% believe there is solid evidence of this, though no such evidence exists. Some 59% of GOP voters say that believing the election was stolen is an important part of their own partisan identity.

“Long after there was no chance of anything mattering for the outcome of an election, and there was nothing that was still remaining to be adjudicated, people just went on and on in continually making these claims, ” says Matt Grossmann, director of the Institute for Public Policy and Social Research at Michigan State University. “And politicians were asked to repeat them – or face electoral challengers.”

Spreading to other political contests

With former President Trump pushing down from the top, and voters from his base pushing up from their states and local areas, the stolen-election falsehood has spread beyond the presidential level into lower political contests.

- In California, Trump-backing talk show host Larry Elder posted a “Stop Fraud” page on his campaign website where voters could post affidavits of suspicious activity prior to the Sept. 14 recall election, won handily by Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom. Mr. Elder, however, did concede on election night.

- In Nevada, Senate candidate Adam Laxalt – whose father and grandfather were both senators – has raised fears of voter fraud and talked about mounting preemptive legal challenges, 13 months prior to midterm elections.

- In Pennsylvania, former GOP member of Congress and current gubernatorial candidate Lou Barletta wrote in an opinion piece earlier this year that “we’ve always known that dead people have voted in Pennsylvania elections, but recently we’ve made it so they don’t even have to leave the cemetery to do so.”

In addition, Mr. Trump has endorsed allies to try to topple elected Republicans who deny his claims of election fraud, such as GOP Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming. In Georgia, the former president has endorsed GOP Rep. Jody Hice to run against Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a Republican who refused Mr. Trump’s request to find votes to overturn Mr. Biden’s win in the state.

Secretary of state can be an important post, as in many states it is the top official in control of election machinery. Last week Reuters examined the backgrounds of all 15 Republicans running for secretary of state in five battleground states. Ten of them continue to question whether Mr. Trump lost in 2020, according to the news service.

“Loyalty to Trump has become the defining issue of the Republican Party,” says Professor Hopkins.

Wrap all this together, and what the United States is experiencing is a crisis of governance, an attempt to turn previously accepted methods for determining who runs America into new battlegrounds, said speakers at a conference on election subversion held last week by the Fair Elections and Free Speech Center at the University of California Irvine School of Law.

Partisan “audits,” spurious fraud charges, frivolous lawsuits – they all layer a new politicized process over normal methods of counting votes and certifying elections, said Bob Bauer, a New York University law professor and former Obama campaign general counsel.

“If that catches on it would be absolutely disastrous,” said Mr. Bauer.

After all, the goal of the Trump “big lie” is not just to adjudicate an election that’s already occurred. It’s to prepare the way for further such actions in the 2022 midterms and 2024 presidential election.

“The goal is to throw up a lot of smoke and confusion,” said Sarah Longwell, a Republican political strategist and publisher of the conservative website The Bulwark. “Donald Trump is winning a narrative war.”

Overall, the U.S. is facing perhaps a 30% chance that the country will experience a breakdown of democracy by 2024, said Larry Diamond, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and author of “Ill Winds: Saving Democracy From Russian Rage, Chinese Ambition, and American Complacency.”

“The imperative is the defense of democracy over all else,” Professor Diamond said.

Virginia governor’s race: What does ‘pro-business’ mean in a pandemic?

With the economy and public health increasingly linked, will voters see mask and vaccine mandates as helping businesses or hindering them? The Virginia governor’s race may provide a test case.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

For years, Republican candidates have cast themselves as “pro-business” by hewing to a platform of tax cuts and deregulation. But 18 months into a global pandemic, the definition of “pro-business” may be shifting, with many voters now seeing the economy and public health as inextricably linked.

In Virginia’s gubernatorial election, where polls show a tight race with just five weeks to go, former Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe is arguing there will be no real economic recovery until the pandemic is contained – and that mask and vaccine mandates are business-friendly measures.

“Businesses support vaccination,” Mr. McAuliffe says. “I want to build a booming economy again, and you can’t do that with COVID. Businesses are not going to move to a county with sky-high rates of COVID and low rates of vaccinations.”

His Republican opponent, former CEO and first-time politician Glenn Youngkin, says many business owners have told him they don’t want mandates imposed on them and their employees. He believes the policy could backfire and actually hurt economic growth.

“If businesses want to act, then it is the business’s decision,” says Mr. Youngkin. “Mandates are not the answer.”

Virginia governor’s race: What does ‘pro-business’ mean in a pandemic?

At Todos Supermarket, one of Virginia’s largest Hispanic grocery stores, Republican gubernatorial candidate Glenn Youngkin is making the case for his pro-business agenda.

Working a stint at the cash register, he hands one woman her change. “I hope you know how to count money, unlike the current governor,” she quips.

The former CEO explains his plan to eliminate the grocery tax, suspend the gas tax, and invest in education – all of which sound great to Todos’ owner, Carlos Castro.

But Mr. Castro says he has a more pressing concern right now: curbing COVID-19.

Pandemic-induced shortages of equipment, supplies, and labor have delayed the opening of his second Todos store. Enhanced unemployment benefits, he says, have made it difficult to retain staff. And it’s been a constant battle to encourage customers to wear masks and employees to get vaccinated.

For years, GOP candidates like Mr. Youngkin have cast themselves as “pro-business” by hewing to a platform of tax cuts and deregulation. But 18 months into a global pandemic, the definition of “pro-business” may be shifting, with many voters now seeing the economy and public health as inextricably linked. Democratic candidates such as former Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe – who’s locked in a tight race with Mr. Youngkin – are leaning into that position, arguing that mask and vaccine mandates are, in fact, business-boosting measures, and that there will be no real economic recovery until the pandemic is contained.

With early voting already underway in Virginia and just five weeks until Election Day, the issue is shaping up as a critical test of how the politics of the pandemic could play out in next year’s midterm elections.

“The vaccine mandate is really controversial with a lot of Republican voters,” says GOP strategist Alex Conant. “But some business owners welcome the mandates. It allows their employees to be mad at Biden and not them.”

That’s certainly the case for Mr. Castro, who says he’s more than happy for the federal government to step in.

“It’s a blessing for us, because we don’t have to deal with it,” says Mr. Castro. “Now I don’t have to be fighting with anybody.”

A sharp partisan split

Under the new requirements announced earlier this month by President Joe Biden, employers like Mr. Castro with 100 or more employees must soon have a fully vaccinated workforce or provide weekly testing. Federal workers must be vaccinated or face losing their jobs. Altogether, the mandates will apply to two-thirds of American workers.

In his speech, President Biden noted that many major companies – such as Fox News – have already implemented similar restrictions on their own.

“If you look at the polling, businesses support vaccination,” says Mr. McAuliffe, a former Democratic National Committee chair who served as Virginia’s governor from 2014-2018. “I want to build a booming economy again, and you can’t do that with COVID. Businesses are not going to move to a county with sky-high rates of COVID and low rates of vaccinations.”

Democrats believe this message – that a healthy economy first means controlling the pandemic – is a winning one. In his recall election victory speech two weeks ago, California Gov. Gavin Newsom said the outcome was a vote for vaccines and “ending this pandemic.”

“Voters in California didn’t like that Newsom had that fancy dinner [during lockdown], but they thought that it’s better to have this set of pandemic politics than what you get with a Republican,” says Bill Kristol, a conservative commentator and prominent Trump critic, who has endorsed Mr. McAuliffe in the Virginia governor’s race. “If you look at the world over the past 200 years, it’s good for the economy to have good public health.”

According to a recent poll by Morning Consult, 58% of Americans support the Biden administration’s vaccine mandates. But there’s a big partisan split, with 80% of Democrats but only one-third of Republicans in favor.

Former President Donald Trump has harshly rebuked the vaccine requirements, as have Republican governors across the country. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis told his state’s cities and counties they would be fined $5,000 per employee if they require public workers to be vaccinated; Texas Gov. Greg Abbott had already issued an executive order banning vaccine requirements. Mississippi’s governor called Mr. Biden’s mandates a form of “tyranny,” and South Carolina’s vowed to fight Mr. Biden to “the gates of hell.” Republican attorneys general from 24 states have threatened legal action.

Mr. Youngkin, who has emphasized that he is a strong proponent of vaccination, says many business owners have told him they don’t want mandates imposed on them and their employees.

“The vaccine is the best way for people to protect their health, but it is an individual’s decision. If businesses want to act, then it is the business’s decision,” says Mr. Youngkin. “Mandates are not the answer.”

The first-time politician is walking an especially delicate line in Virginia, a former swing state that turned decidedly bluer over the past decade. Ranked CNBC’s “top state to do business” for the past two years in a row, Virginia will likely have its gubernatorial election decided by turnout in the increasingly Democratic suburbs outside Washington, where many voters support stronger steps to prevent the virus’s spread.

“Republicans are sick of the pandemic too,” says GOP strategist Whit Ayres. “A reflexive less-regulation message may not be effective when it comes to dealing with the pandemic.”

“We need to get the economy moving”

But general concerns about the economy – even if stemming from the pandemic’s effects – could still work to Mr. Youngkin’s benefit. In a recent Washington Post-Schar School poll, registered voters in Virginia ranked the economy as the top voting issue in November’s election, followed by the coronavirus. While voters trusted Mr. McAuliffe to do a better job handling the pandemic by 44% to 35%, Mr. Youngkin had a one-percentage-point edge on handling the economy.

“For business owners, there is a lot more that goes into [their vote] than ‘Do you support vaccine mandates?’ – and those are the reasons that they have traditionally supported Republicans,” says Mr. Conant, the GOP strategist.

Mr. Castro, for his part, says he hasn’t decided for whom he will vote. He backed Mr. McAuliffe in 2014, and thought he was a good governor. But he also says he believes in “political diversity” and wants to support more moderate Republicans, who might steer the party toward the center on issues like immigration. As an employer, he’s worried that pro-union Democrats in Congress may weaken or even nullify Virginia’s “right to work” law.

Still, he says his vote will likely come down to which candidate will end the pandemic more quickly – and right now, he believes that’s Mr. McAuliffe.

“We need to get people back to work,” says Mr. Castro. “We need to get the economy moving.”

How Chattanooga is working to right the wrongs of urban renewal

Call it inequitable urban planning: In a bid to ease traffic flow, some cities built roads and highways that hemmed in low-income neighborhoods. Here’s how one major Tennessee city is trying to redress that de facto segregation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

America’s highways were the crowded envy of the world, a midcentury engineering marvel that connected a massive country with high-speed lanes and high-volume trucking. But as they cut through cities, the barriers formed by the highway system often had racial meaning and intent.

Nearly fully funded by federal dollars but often guided by local discretion, highways running through Black neighborhoods segregated and displaced Black people while opening up real estate opportunities largely captured by suburban whites.

“The devastation was systematic and complete,” destroying community commerce and paving over history, all with little compensation for those impacted, says Robert Bullard, co-editor of “Highway Robbery.”

In Tennessee, Chattanooga’s Westside housing project exemplifies the point. Hemmed on nearly all sides by highways, it is a physical manifestation of the economic and social dislocation caused by a massive infrastructure project.

Cities reckoning with a similar legacy from the urban renewal era are making efforts to mitigate the harm done. But Chattanooga is ahead of the curve in having experience with downsizing roads and in engaging the community in planning. It’s also taking seriously this punch list by Dr. Bullard: Involve impacted communities, convert land to mixed-income housing to discourage gentrification, and put a premium on preserving local culture.

How Chattanooga is working to right the wrongs of urban renewal

When the freeways came to Chattanooga over half a century ago, Black neighborhoods like Violet Hill and Blue Goose Hollow disappeared into the dirt, sacrificed to asphalt.

Notched between Lookout Mountain and Raccoon Mountain, the city rose to 11th place in the U.S. for per capita spending on new highway projects during the urban renewal era. At the same time, Chattanooga built Westside, a 200-acre, warren-like public housing project for those displaced by what many white Americans saw simply as progress.

Several generations later, the brick tenements are now a “distressed asset,” set for the wrecking ball.

Hemmed on nearly all sides by highways, Westside is a physical manifestation of the economic and social dislocation caused by some of America’s massive infrastructure projects. Peter Norton, associate professor of history in the engineering school at the University of Virginia, calls it “the Berlin Wall effect.”

Embedded in the highways that wall off Westside are values that, at least in the past, accepted taxpayer-funded disconnection of Americans based on race, class, and the ability to fight back politically. Today, the area is so cut off from grocery stores that foodstuffs dominate the local black market.

Now the question for Chattanooga – and elsewhere – is whether those poured-in-cement values are changing. Across the country, cities are grappling with the effects of urban renewal and, in some cases, trying to redress the harm done. They hope that removing or modifying highways can restore economic, social, and cultural exchanges to places once walled off by concrete.

“There are plenty of cases where [highways] can be removed or redesigned as boulevards to benefit the local community,” says Dr. Norton.

What do smaller roads offer?

Chattanooga, for one, already has learned the power of downsizing. When it turned Riverside Parkway from a four-lane trucking road to a two-lane boulevard in 2004, it saw a renaissance. Real estate values boomed as the riverfront became accessible to developers. Westside didn’t feel the benefits of that boom, though.

“In a way the risk here is that, in trying to undo the damage of urban renewal ... we might repeat it. Some of these highway redesign efforts have a gentrifying effect, and that doesn’t improve the equity picture,” says Dr. Norton, who is also the author of “Fighting Traffic.”

Indeed, whether such effects can be guided equitably is far from clear for cities from New Orleans to Miami, as municipal leaders try to balance demands for social equity with the needs of some 250 million U.S. drivers, many of them stuck in weekday gridlock.

“Something has got to give, and the thing that can’t give is ... road capacity,” says Gary Biller, president of the National Motorists Association, an advocacy group in Waunakee, Wisconsin. “So, count us as skeptics when it comes to the reimagining of city life and urban living, because a lot of it is theoretical. People still do need to get around.”

Yet experience doesn’t bear out many drivers’ worst fears. Like Chattanooga’s downsizing, Seattle, San Francisco, Boston, and Rochester have all removed or modified major highways without dramatically increasing commute times. (Those times, in cities such as Boston, were already high.) In nearly all those cases, local communities have benefited, while drivers have found other routes or made different traveling decisions.

How did we get here?

Despite the headaches and heartaches, America’s highways are the crowded envy of the world, a midcentury engineering marvel that connected a massive country with high-speed lanes and high-volume trucking – in some ways, the cornerstone of the nation’s world-leading $22.7 trillion gross domestic product.

But as they cut through cities, the barriers formed by the highway system often had racial meaning and intent.

Former Atlanta Mayor William Hartsfield spoke plainly when he said the new interstates planned in the late 1950s would serve as “the boundary between the white and Negro communities.” But it wasn’t just a Southern issue. Chicago’s interstates in many ways still serve as racial boundaries, notes Dr. Norton.

Nearly fully funded by federal dollars but often guided by local discretion, highways running through Black neighborhoods served a purpose besides simply segregating Black people – and displacing more than a million people. The highways opened up real estate opportunities largely captured by suburban whites.

“The devastation was systematic and complete” as highways displaced homeowners and renters, destroying community commerce and paving over history, all with little compensation for those impacted, says Robert Bullard, co-editor of “Highway Robbery” and professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Christian University. “The infrastructure that was being put in place was destructive infrastructure, was discriminatory infrastructure.”

One win in an ongoing battle

Americans have seen the potential for such damage all along.

In the Fairfax, Virginia, neighborhood of Gum Springs, founded by a Black man once enslaved by George Washington’s family, local residents took to the streets as early as 1967. They protested a proposed highway expansion by pulling a casket across the highway.

Neighbors won that fight. But they are again facing a proposed expansion of the Richmond Highway. Notably, Gum Springs is the only stretch where there’s thought of expanding to 13 lanes. Local groups have already succeeded in delaying a county vote on the proposal.

When building highways through poorer communities, “you are separating and dividing the Black community socially and culturally, and you are also eroding the heritage of the community,” says Gum Springs resident Queenie Cox.

Basically, the effort to scale back the Gum Springs expansion, she says, is “just having equity and being treated like the other communities in the Mount Vernon district.”

Ms. Cox knows that push for equity faces tremendous forces.

Massive new highway projects are planned to alleviate traffic in Orlando, Florida; Austin, Texas; and Charleston, South Carolina, to name a few. Some would require more razing of so-called sacrifice communities.

Addressing aging roads and redressing harm

The moment catches America at a crossroads: Much of its highway infrastructure is approaching its engineered lifespan. Meanwhile, about 100 million more people now live in the U.S. than when these roads were first built. But the need goes beyond updating or replacing what exists.

President Joe Biden’s original infrastructure bill included $20 billion to remove or modify highways to boost prospects for poorer Americans living in those areas. And even though Senate negotiations slashed that amount to $1 billion, and the bill’s fate is currently unclear in the House, about 30 U.S. cities are looking into ways to deconstruct.

As part of a Florida Department of Transportation campaign, Overtown, a historically Black neighborhood in Miami decimated by a highway overpass in the 1960s, is getting a redesigned intersection to improve access, provide park space, and connect the community to Biscayne Bay. In Atlanta, leaders are considering an idea called The Stitch that would reconnect downtown across the asphalt gorge known as the Connector. New Orleans is closer to removing the Claiborne Expressway that splits and overshadows the historic Treme neighborhood.

But with its experience downsizing and a community-based approach to urban planning this time around, Chattanooga is ahead of the curve. The city is among the first to plan for infrastructure changes that would directly address past hurts.

Eric Myers, executive director of the Chattanooga Design Studio, is leading community input sessions that have included town halls and street fairs. Part of the gambit is to reimpose a block structure that he says is key for neighborhoods to thrive. The group, he says, is looking at how structures can be modified to improve access and flow. Also, the extent to which the city’s experiences with Riverside Parkway and its bike paths can be extended to Westside, he says, will likely be key to an urban reunion effort that, planners hope, would benefit a more diverse group of Chattanoogans.

As part of these conversations, the city is taking seriously a punch list by Dr. Bullard: Involve impacted communities, convert land to mixed-income housing to discourage gentrification, and put a premium on preserving local culture.

“The question we are all trying to answer is, how do we knit and stitch Westside together back into downtown so it’s not physically and socially isolated?” says Mr. Myers.

Dorothy Talley, a lifelong resident of the Westside neighborhood, counts herself among the skeptics. That the same government that once tore neighborhoods up is now going to reckon with that legacy by opening up Westside for development that will somehow, in the end, benefit poor people seems to her a bit, well, rich.

“I feel like we are being told another tale,” she says.

Others are more hopeful. The damage wrought by the highways can’t be completely undone, says Joseph “Jo-Jo” Koller, another longtime Westside resident. But he has watched how the shift of Riverside Parkway dramatically reshaped the city nearly overnight.

If those benefits can be extended to the people of Westside, it would seem to him a long overdue acknowledgment of the impact of highways on humanity.

“We may be poor, but we are still here. We’re still breathing,” says Mr. Koller. “We’re human beings, too.”

Points of Progress

Taking better care of people: Silver Alerts, non-English driver’s tests

Our latest roundup of progress ranges from the invention of a new self-healing material to fresh techniques to study the world’s most impenetrable jungles.

Taking better care of people: Silver Alerts, non-English driver’s tests

In addition to looking at how two governments are expanding inclusivity in very different ways, we also see how economics and technology are used to approach problems from a new perspective for deeper understanding.

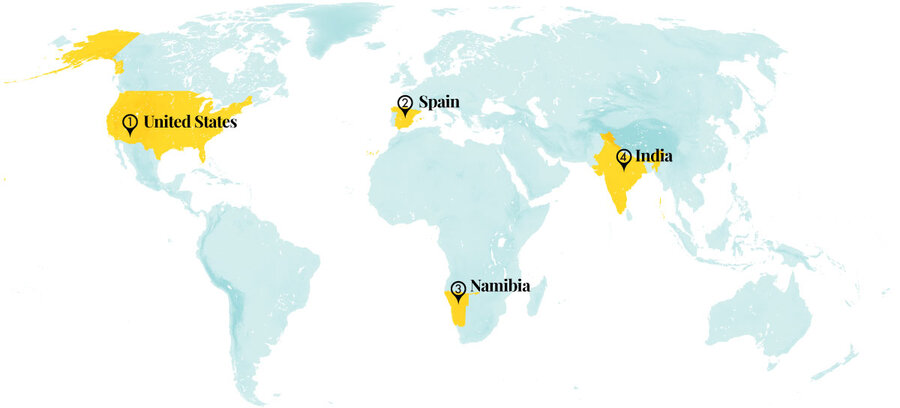

1. United States

Arizona’s expanded Silver Alert system is helping recover missing persons with developmental disabilities. Originally designed for missing older adults diagnosed with dementia, Silver Alerts function similarly to Amber Alerts, with public notices issued through highway signs, news broadcasts, phone messages, and social media. Advocates say that young people with autism and other developmental disability diagnoses have a high rate of wandering away from caregivers or safe areas, and in 2018, they successfully lobbied for these populations to be included in Arizona’s Silver Alert system. Now the disappearance of a person with intellectual or developmental disabilities can also trigger an emergency alert, encouraging statewide coordination and unlocking special search tools.

The overall number of individuals safely recovered following a Silver Alert grew from 60 in 2015 to 131 last year, according to state figures. While the Department of Public Safety does not track age or disability information for each case, anecdotal evidence suggests the expanded criteria have been a success. Last summer, for example, a 13-year-old was spotted on a train between Phoenix and Tempe after an emergency alert spread his information on social media. Other states, such as Illinois and Alabama, have made similar changes to their alert systems in recent years. And in 2018, the federal government established an alert network for missing at-risk adults, including those with mental or physical disabilities who do not qualify for Amber or Silver Alerts.

Cronkite News

2. Spain

A new study reveals the economic and environmental benefits of a marine protected area (MPA) off the Spanish island of Mallorca. Established in 2007 at the request of a local fishermen’s association, the 27,000-acre Llevant marine reserve has boosted biodiversity, slowed coastal erosion, and improved fishing conditions. And research shows MPAs such as Mallorca’s have far-reaching benefits that can outweigh their maintenance costs.

The recent study, conducted by the nonprofit Marilles Foundation as part of a wider project to improve marine management throughout Europe, is the first to apply a “natural capital accounting” framework to one of Spain’s MPAs. Its analysis looked at Mallorca’s protected area as a national asset, and incorporated the cost of maintaining the MPA and its associated services into the country’s economic profile. It found that for every euro invested in the MPA, the area generated €10 in tourism, leisure, and fishing benefits. Annually, the Llevant reserve costs about €473,000 ($556,000) to maintain and generates more than €4.8 million ($5.6 million), according to the study. Authors note this sum does not include the added value of maintaining jobs in the region’s declining fishing sector. “Marine protected areas deliver fish and much more,” said Marilles director Aniol Esteban. “Investing in them pays off.”

The Guardian, Ecoacsa Reserva de Biodiversidad

3. Namibia

In Namibia, aspiring drivers can now take their learner’s license exam in their local language. Language has been a contentious issue here. When the country gained independence from South Africa in 1990, the government chose English as the official language, because it was seen as a neutral choice in a nation where 30 languages are spoken. But very few people actually spoke English, and as recently as 2012, studies showed most public school teachers had a weak grasp on the language of instruction. Commentators say the lack of English competency throughout the country limits opportunities for many Namibians.

The Roads Authority has taken steps to address the country’s multilingualism in driver training. The learner’s license exam – one of the first steps for Namibians to get on the road – is now offered in several languages other than English. These include Oshiwambo, a language spoken at home by nearly half the population, which will be offered in 18 cities and towns throughout the country. The siLozi language, spoken by about 4% of Namibians according to the 2011 census, will be offered in the capital city of Windhoek and the northeast city of Katima Mulilo. Other options include Afrikaans, Khoekhoegowab, Otjiherero, and Rukwangali, with the Roads Authority planning to introduce more language options. All language options are available in the capital.

The Namibian, New Era, Roads Authority, The Guardian

4. India

Scientists in India have identified the world’s hardest self-healing material, which could have applications in aerospace engineering and consumer electronics. Self-healing materials have been studied for decades, especially as a means to extend the life spans of buildings, automobiles, and kitchen products. Yet most of the world’s known self-healing substances are soft and opaque, and often require activation through heat or light exposure, limiting their uses. Researchers from the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research and the Indian Institute of Technology have synthesized a piezoelectric crystal – meaning it can convert mechanical energy into electrical energy – that appears to overcome these shortfalls.

In a paper published by the journal Science, the team showed how they created small fractures in the crystal using a needle. Because of the material’s crystalline structure, and the energy created by the break, the fragments then rejoined with what one researcher described as an “acceleration comparable to diesel cars.” “The material that we found can’t be used directly for mobile phone or TV screens,” said lead researcher Chilla Malla Reddy. “But our work on understanding the science of developing such materials may lead to futuristic technologies such as self-healing screens.”

The Telegraph, Deccan Herald

World

Advancements in arboreal camera trapping are helping fill gaps in forest research. For decades, on-the-ground camera traps have helped scientists create species inventories, observe wildlife behaviors and interactions, and understand how human activities affect forests. But until recently, the forest canopy has remained a mystery.

Although tree-dwelling species play important roles in maintaining forest ecosystems and are vulnerable to deforestation, they’ve largely gone unstudied due to challenges accessing their arboreal habitat. With advances in camera and climbing equipment, that’s starting to change, and researchers have discovered new species populations and assessed conservation methods using high-mounted camera traps. A recent paper published in the journal Methods in Ecology and Evolution examined the burgeoning arboreal camera-trapping field. By assessing 90 treetop studies across two dozen countries, the authors provide guidance on tree-climbing safety, choosing the correct camera mounts, and other challenges specific to arboreal research. Standardizing arboreal camera-trapping techniques is important, they say, because it allows data to be compared across many projects.

Mongabay

Difference-maker

They found hope in Afghanistan. Now they strive to preserve it.

Did you know that there are scout troops in Afghanistan? Meet the duo who trained Afghan boys and girls for community service and now face fresh challenges following the takeover by the Taliban.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Marnie Gustavson developed a fondness for Afghanistan during an idyllic childhood exploring Kabul in the late 1960s, when her father taught in the country. After a career running nonprofits in the United States, she returned to Afghanistan in 2004 and volunteered at PARSA, a small Kabul nonprofit aiding impoverished Afghan women, children, and orphans.

In 2006, she took the helm, expanding PARSA’s mission of building healthy communities and increasing its annual funding more than tenfold.

Mohammad Tamim Hamkar, who grew up amid Afghanistan’s turmoil – Soviet occupation, civil war, Taliban repression – joined PARSA with the goal of reviving Afghanistan’s scouting program. Having learned to adapt as his family’s fortunes fluctuated under changing regimes, he appreciated scouting as a vital part of youth education.

“All these activities are supporting young people in learning leadership, honesty, citizenship,” and hard work, he says.

Together they have transformed the lives of thousands of poor Afghan girls and boys, but in August, their joint dream suddenly took an uncertain turn as the Taliban surrounded Kabul.

“What is going on in this country?” Mr. Hamkar said to Ms. Gustavson, as they cried together. “What should we do?” There were, they knew, no easy answers. Yet it wasn’t long before Mr. Hamkar vaulted into action.

They found hope in Afghanistan. Now they strive to preserve it.

She is the daughter of an American biology instructor, and spent an idyllic childhood exploring Kabul under a peaceful monarchy in the late 1960s, when her father taught in Afghanistan.

He is the son of an Afghan army officer, and grew up amid the turmoil of the 1980s Soviet occupation, civil war, and then Taliban repression.

For the past decade, on the outskirts of Kabul, Marnie Gustavson and Mohammad Tamim Hamkar have worked together on a rural compound surrounded by almond and peach orchards, quietly running a small nongovernmental organization that has transformed the lives of thousands of poor Afghan girls and boys through leadership training and community service.

But in August, the dream they pursued together suddenly took a nightmarish turn. As Taliban militants emboldened by the sudden departure of Western military forces captured one major city after another over the span of days – rapidly surrounding the Afghan capital – Mr. Hamkar felt overwhelmed by sadness. He looked over at Ms. Gustavson, her face registering a similar dread.

“What is going on in this country?” Mr. Hamkar said, his voice shaking as they cried together. “What should we do?”

His question hung in the air, as the shock of the uncertainty they faced sank in. There were, they both knew, no easy answers.

Nevertheless, it wasn’t long before Mr. Hamkar vaulted into action.

“Adventure around every corner”

For Ms. Gustavson, the journey that brought them to that moment began with her embrace of the tightly knit Afghan culture as a preteen and teen in 1960s Kabul.

“There was a close community, an adventure around every corner,” she recalls. Her family had no television. They had a phone, but she didn’t know the number. “We entertained ourselves,” she says.

Yellowing photos from a family album capture her perusing cloth in a crowded bazaar, climbing around ancient ruins and flag-festooned graveyards, and sitting in a courtyard in her plaid skirt and black tights listening to village musicians.

What she learned to love most was the conversation. “Afghans are wicked funny people,” she says.

That fondness led her to return to Afghanistan to live in 2004, after a long absence during which she raised her own family and established a career running nonprofit organizations in the United States. Back in Kabul, she volunteered at PARSA, a small nonprofit aiding impoverished Afghan women, children, and orphans.

Stanford-educated physical therapist Mary MacMakin had founded PARSA in 1996 under Taliban rule, and ran several secret schools for women. The Taliban briefly jailed and then expelled Ms. MacMakin, but after the U.S.-led military invasion overthrew the Taliban in 2001, she returned to Kabul.

In 2006, she asked Ms. Gustavson to take the helm of PARSA. Under her leadership, PARSA has expanded its mission of building healthy communities and increased its annual funding more than tenfold.

In 2008, PARSA moved onto the large, semirural compound of the Afghan Red Crescent Society (ARCS), which includes a traditional Afghan refuge – a marastoon, or place of help – that had been created in the 1930s for destitute widows, orphaned children, and disabled people. With a staff of 120, PARSA helps many of the marastoon residents as part of its wide-ranging programs.

“It’s like a village,” says Ms. Gustavson, who was living in a nearly 100-year-old ARCS house that was rebuilt from ruins, surrounded by a community of some 300 people as well as cows, horses, and fields. “I am with people all day long.”

A major advance came in 2010, when Mr. Hamkar joined PARSA with the goal of reviving Afghanistan’s beleaguered scouting program. Dating back to 1931, scouting in Afghanistan experienced several incarnations, growing to 36,000 members before it came to a halt after the Soviet Union invaded in 1979.

Commitment to scouting

Growing up in Baghlan province north of Kabul in the 1990s, Mr. Hamkar had learned to adapt as his family’s fortunes fluctuated under changing Afghan regimes – picking up farming, greenhouse agriculture, and business skills at a young age.

“I started my private business, an ice cream shop,” while still in high school, he says.

Such life experiences helped him appreciate Boy Scout merit badges, but it was in college, at Kabul Polytechnic University, that Mr. Hamkar discovered the power of scouting as a vital part of youth education.

“All these activities are supporting young people in learning leadership, honesty, citizenship,” and hard work, he says.

At PARSA, Mr. Hamkar found in Ms. Gustavson someone who could share his dream. One day, he took her aside and asked for her pledge – to build a sustainable, long-term scouting program.

“Scouting is not a project to start one year and stop the next. I am not doing this,” he told her. “We must make a program. Can you promise me?”

She agreed.

Ten years later, with PARSA’s help, Afghanistan had trained 600 scoutmasters and had nearly 11,000 active scouts in 34 provinces. In 2020, it regained its membership in the World Organization of the Scout Movement. “I was very happy,” says Mr. Hamkar.

Their shared vision of empowering youth to take the initiative and serve their communities – by planting trees, digging wells, installing libraries, and other projects – has spread hope, they say. The scouts “are highly motivated and quite independent ... which is not Afghan tradition,” says Ms. Gustavson.

Indeed, colleagues say Ms. Gustavson stands out as an NGO leader for nurturing boldness in both her staff and Afghan youth.

“Marnie encouraged them to be outspoken leaders, which is not typical,” says Mark Ward, a retired senior U.S. diplomat and former country director in Afghanistan for International Medical Corps.

“They hear my voice”

From her mud-brick home on the side of a mountain overlooking Kabul, Zohra, an Afghan scout, walks for an hour to fetch water to help sustain her family of 10 people. After Zohra’s father died, her mother and siblings, then considered orphans, moved into the marastoon near PARSA eight years ago to escape starvation.

Today Zohra, who is using a pseudonym for her protection, credits PARSA for believing in her, and helping her realize her own potential. “PARSA is a place where they hear my voice, and they respect me as a human,” she says by phone from her mountainside home.

A competitive long-distance runner, straight-A high school senior, fluent English speaker, and leader in training other local youth, Zohra helps support her family while her mother works, caring for the marastoon’s mentally disabled residents for $80 a month.

“Marnie is like my mother,” she says. “She helped me and so many orphans to have facilities to learn, to set goals for ourselves, and to have hope for the future.”

Mobilized youth

After his tearful meeting with Ms. Gustavson in August, Mr. Hamkar had an idea. He rallied Zohra and other scouts, and gathered up tents, sleeping bags, blankets, and camping gear.

Thousands of Afghans fleeing the Taliban advance were huddling in Kabul in the hot sun without water and other basic supplies. The scouts sprang into action, setting up a protected village with 60 tents in a local park. Within hours, the scouts were caring for 45 families, providing food, water, toilets, and first aid, and ensuring the village was safe.

“There was no fighting, no stealing – the camp was supervised by the scouts,” says Mr. Hamkar.

For a week, the scouts cared for hundreds of displaced people, but on Aug. 15, a Sunday, the Taliban swept into Kabul, forcing the young volunteers to pull back.

Taliban fighters overran PARSA’s compound, stealing three trucks and temporarily detaining a staff member. Meanwhile, Ms. Gustavson had made the wrenching decision to evacuate for her safety, boarding the last commercial flight out of Kabul for Dubai just a few hours before.

Mr. Hamkar was stunned by the collapse of the Afghan police and army. “Everything changed in front of my eyes in six hours,” he says in a call from Kabul.

After lying low for two days, he returned to PARSA, only to have the Taliban arrive and demand he take them alone into his office. Two men in black turbans questioned him, while a third stood at the door with a U.S. military rifle.

“Tell me the truth!” the oldest of the Taliban said. “We found you are teaching Christianity!”

Mr. Hamkar, knowing the Taliban ways, says he stood strong, and let out a loud laugh.

“Who told you we are doing this illegal activity against Islam?” he demanded back, adding that PARSA’s staff has 119 Muslims and one non-Muslim, Ms. Gustavson. “How is this possible?”

The Taliban backed down, he says, and within days, Mr. Hamkar had obtained an official letter allowing PARSA to remain open.

Seeking a path forward

In the modern, street-level office of her sister’s West Seattle town house, with its gleaming windows and cold, concrete floors, Ms. Gustavson seems out of place in her earthy maroon tunic and dangling blue lapis earrings. Three weeks after she fled Kabul, she feels dislocated, too.

“I am not functioning that well here yet,” she says, staying up most nights on calls to Afghanistan.

Mr. Hamkar understands. “She is physically in the U.S., but emotionally she is always here,” and eager to return, he says. “I told her, ‘Please, Marnie, don’t hurry; everything is still unclear.’”

Frustrated by the intense focus on evacuations, Ms. Gustavson says PARSA is concentrating on humanitarian aid for the people left behind. Knowing the Taliban needs its help, a coalition of NGOs including PARSA is pressing them to allow women to work.

Mr. Hamkar, meanwhile, faces the challenge of explaining scouting to the mullah in charge of the education ministry, in a bid to gain permission for it to continue. “We had a dream for this country,” he says, his voice trailing off. “I am sad and very, very tired.”

For her part, Zohra stays close to home, restrained by the Taliban’s ban on sports and school for teenage girls. But far from giving up, she exercises daily indoors. And she has quietly started teaching English and public speaking to other homebound young women.

“We are still trying,” she says, “and we are still alive.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A youth-led movement against Malaysia’s race-based politics

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Two years ago, just before the pandemic, a wave of youth-led protests hit several Muslim countries, from Sudan to Lebanon to Iraq. While the main goal was democratic reform, protesters also shared a second demand: End political favoritism along ethnic or religious lines. Now because of the pandemic, young people in another Muslim country, Malaysia, are on a similar march.

In July, young Malaysians took to the streets to protest the government’s poor handling of the pandemic. The prime minister was forced to resign, and his replacement made a key concession to activists. He ended government efforts to block a law that was supposed to lower the voting age. Now 18- to 20-year-olds will soon be able to cast ballots, giving greater influence to young people in reshaping Malaysia’s democracy. That influence could end up challenging the country’s race-based policies that grant economic favors to the majority Malay ethnic group.

Last year, a youth-led political movement sprang up to end such discrimination and create inclusive politics. A new spirit of civic equality has emerged in Malaysia, much like that in other Muslim countries divided by ethnicity or religion.

A youth-led movement against Malaysia’s race-based politics

Two years ago, just before the pandemic, a wave of youth-led protests hit several Muslim countries, from Sudan to Lebanon to Iraq. While the main goal was democratic reform, protesters also shared a second demand: End political favoritism along ethnic or religious lines that aids corruption. Now partly because of the pandemic, young people in another Muslim country, Malaysia, are on a similar march.

In late July, young Malaysians took to the streets to protest the government’s poor handling of the pandemic in the Southeast Asian nation. Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin was forced to resign. Then in September, his replacement, Ismail Sabri Yaakob, made a key concession to activists. He ended government efforts to block a 2019 law that was supposed to lower the voting age. Now 18- to 20-year-olds will soon be able to cast ballots, giving greater influence to young people in reshaping Malaysia’s democracy.

That influence could end up challenging the country’s race-based politics. For decades, the government has granted economic favors to the country’s majority Malay ethnic group, which is largely Muslim. That resulted in official discrimination against ethnic minorities, notably Chinese and Tamil. Last year, a youth-led political movement sprang up to end such discrimination and create inclusive politics.

“Young people are not susceptible to racial politics,” said the movement’s founder, Syed Saddiq Syed Abdul, a former lawmaker and government sports minister who is 28 years old. “They are more concerned about influencing their actual policies.” He hopes to register the movement as an official political party, the Malaysian United Democratic Alliance, or MUDA, which means young in the Malay language.

A new spirit of civic equality has emerged in Malaysia, much like that in other Muslim countries divided by ethnicity or religion. With access to social media, young people are able to bypass government-controlled news and read about their shared interests.

In July last year, 222 young Malaysians held a two-day “digital parliament” reflecting the real Parliament to discuss and “pass” new laws affecting youth. The virtual meeting drew more than 200,000 viewers. They saw a potential for a new Malaysia, one that treats all citizens as individuals, endowed with the same dignity and freedom of conscience, and with equal moral standing.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Are we living in a post-truth era?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Eric Nelson

Sometimes it can seem as if facts take a back seat to opinion or emotion. But getting to know God as infinite, pure Truth itself is a powerful basis for finding clarity, harmony, and mental as well as physical healing.

Are we living in a post-truth era?

Rumor has it that we’re living in a post-truth era. “Post-truth” is defined as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief” (lexico.com). While this may be an apt description of what appears to be going on within the current political arena, “post-truth” is not a term I would use to describe the world in which we actually live. And here’s why:

As a Christian Scientist, I’ve come to appreciate Truth – with a capital T – not as an all-too-often-subjective representation of fact, but as a synonym for God – infallible and invariable, entirely good, completely pure; as something I can depend on; as that which, even when resisted, finds a way to make its presence known in my life.

So when I hear the term “post-truth” (which I translate as “post-Truth”), I tend to hear “post-God,” and that just doesn’t sync with my experience.

This doesn’t mean that there hasn’t been the odd occasion when I’ve been fooled into believing otherwise. In fact, last November, a couple of days before the presidential election in the United States, I faced just such a situation. My stomach became so painful that it was all I could do to lie down and send a text message to a friend to ask for his prayerful support. As I waited for his response, I opened my Bible – completely randomly – and read, “What aileth thee?” (Isaiah 22:1).

At first I thought, “What do you mean, ‘What aileth thee?’ My stomach aileth me!” But then I realized what a great question it was. And I had to admit that at that moment, what was ailing me most was the notion that I was living in a post-Truth world – a world where the God I had come to know as infinitely good couldn’t be trusted, a world where I couldn’t trust others, a world that seemed to be drowning in a sea of mistrust and fear.

Glancing again at my Bible, I read, “A grievous vision is declared unto me; ... Therefore are my loins filled with pain” (Isaiah 21:2, 3).

I couldn’t have said it better myself!

This connection between what we allow into our thought and our physical well-being is fundamental to the practice of Christian Science. The key, however, isn’t thinking positive thoughts, but rather allowing our thoughts to be governed by God, divine Mind and Love.

“To be immortal, we must forsake the mortal sense of things, turn from the lie of false belief to Truth, and gather the facts of being from the divine Mind,” writes Mary Baker Eddy, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” (p. 370).

By turning to Truth with a capital T, we’re turning to God, not just some abstract idea of truth, subject to the whims of personal interpretation. We’re appealing to that which presents and perpetuates itself in such qualities as honesty and integrity. And when we persistently affirm the all-presence and all-power of Truth, we’re able to relieve ourselves of the discouraging and sometimes debilitating belief of living in a world, or living a life, that is devoid of Truth, devoid of God, devoid of universally and divinely bestowed mental and physical harmony.

So what do we do when we’re bombarded with what seems to be anything but the truth? When we find it next to impossible to have a conversation with someone whose take on truth isn’t in line with our own?

First and foremost, we need to call upon our innate ability to see in ourselves and others the God-given integrity that Christ Jesus saw in everyone. “To this end was I born, and for this cause came I into the world,” said Jesus, “that I should bear witness unto the truth” (John 18:37). This is a reminder of the importance of distinguishing between what is and isn’t true about God and God’s beloved creation, and of recognizing that we each reflect the purity and consistency of Truth itself. When we do this, healing happens.

Praying with these ideas brought me a greater confidence that I could trust God to be God; trust others to be what God created them to be; and understand that Truth’s presence and power make no allowance for fear.

Physically speaking, my situation improved immediately. Within a short time, I was completely free of pain. Even better, though, was the realization that followed: that divine Truth continues to reign supreme.

Adapted from an article published on sentinel.christianscience.com, Aug. 12, 2021.

A message of love

Early morning blues

A look ahead

You’ve reached the end of our package of stories for today, but we’re already hard at work on a fresh set of articles for tomorrow. Among them is an interview with the author of a book about the complex politics of Black women’s hair.