- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Russia as pariah: Has world ever been this united against one nation?

What do the punk rock band Green Day, Delta Air Lines, Shell, Mercedes-Benz, Eurovision, FIFA, the Metropolitan Opera, and Disney have in common? They – and many others – are cutting ties with Russia.

Like a BTS song, standing up to Moscow is going viral.

Beyond the official government sanctions, the speed at which private companies, sports organizations, athletes, and artists have expressed their moral outrage over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is unprecedented.

The closest historical parallel is South Africa. The divestment campaigns and protests against apartheid spawned in 1959 took decades to develop global support. “We’re watching this shift [against Russia] unfold in days,” says historian Zeb Larson. The pace of change, he says, is “striking.” More recent grassroots sanctions movements, such as the pro-Palestinian “boycott, divestment, sanctions” and fossil fuel divestment campaigns, have also been years in the making.

We saw a similar moment of worldwide umbrage and empathy after the 9/11 attacks. “We are all Americans,” the French newspaper Le Monde wrote in a Sept. 12, 2001, headline. History shows us, Dr. Larson says, “conspicuous violence drives moral outrage more than anything.”

To some, Russia’s invasion also smacks of a bullying, colonial mentality. In a widely shared speech, Kenya’s ambassador to the United Nations, Martin Kimani, described Russia’s violation of territorial integrity as “dangerous nostalgia” for empire building.

Will this international shunning be effective or endure? It’s unclear. But it’s unlikely that Russia’s risk assessment included this scale of moral clarity and solidarity.

Also likely unforeseen: Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s open defiance. “It is breathtaking to witness actual courage. It’s even more breathtaking when that courage is both moral and physical,” writes conservative columnist David French. “[Mr. Zelenskyy’s] not just speaking against evil, he’s quite literally standing against evil.”

Apparently, many around the world have found that courage inspiring, and are taking steps to support it.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

The Ukrainian exodus

Our reporter shares some poignant accounts of Ukrainians passing through Lviv, Ukraine, a way station where powerful feelings of compassion, relief, sorrow, and uncertainty play out again and again.

Irina Kopil, the mother of two children, pulled into the train station in Lviv Tuesday morning, fleeing missile strikes in the city of Vinnytsia.

“You feel everything – anger, panic, fear, sadness,” says Ms. Kopil. In a murmur, she shares that her husband, a member of Ukraine’s territorial defense force, stayed behind. “We do not know when we will see each other again.”

Ms. Kopil and her children belong to the ever-rising tide of Ukrainians fleeing the country as Russia’s invasion enters its second week. More than 800,000 refugees have escaped as the Russian military escalates its attacks on cities across Ukraine.

The majority of those displaced by the war find safety in Poland. In Lviv, the last large city before the border, the train station has seen a crush of refugees, whose relief at eluding harm collides with sorrow over leaving home as they journey toward uncertainty.

Ivan Slotylo and Renata Kukul, a Lviv couple, arrived at the station to distribute food to fellow Ukrainians. Mr. Slotylo explains that while the war has largely spared the country’s west, residents here feel solidarity with those forced to flee.

“Putin didn’t just attack some of us. He attacked all of us,” Mr. Slotylo says. “Our country needs us.”

The Ukrainian exodus

Mother held son in her arms as missiles and rockets thundered down on Kharkiv and the entire world sounded as if it might end. In an underground subway station in Ukraine’s second-largest city, Valeriya Portnianka and young Matvey huddled with hundreds of other residents, wondering if they would ever again walk up into the light.

One day blurred into the next, then another. On the fourth day, 94 hours after descending into the gloom, Ms. Portnianka gathered her son and their lone suitcase. They boarded a train from Kharkiv on Ukraine’s border with Russia to the capital of Kyiv, and from there continued west to Lviv. Some 22 hours later, forced to abandon home, work, and the order of life, she clasped Matvey’s hand as they waited to board a bus Tuesday bound for Poland.

“It was ...” She pauses to wipe away tears, her face wan beneath the hood of a blue wool coat. “It was nothing you can describe. It was a feeling of dying while you are alive.”

Ms. Portnianka and her son belong to the ever-rising tide of Ukrainians fleeing the country as Russia’s invasion enters its second week. More than 800,000 refugees have escaped to Poland, Hungary, Moldova, Slovakia, and Romania as the Russian military escalates its attacks on cities across the eastern two-thirds of Ukraine. Defense officials in Kyiv reported Wednesday that more than 2,000 civilians have died.

The majority of those displaced by the war find safety in Poland, where officials estimate that 50,000 Ukrainians arrive daily. In Lviv, the last large city before the border, the train station has seen a crush of refugees, whose relief at eluding harm collides with sorrow over leaving home as they journey toward uncertainty.

Irina Kopil, the mother of two children, pulled into the station Tuesday morning from Vinnytsia. The city of 375,000 people, southwest of Kyiv and home to the headquarters of the Ukrainian air force, has absorbed missile strikes as air-raid sirens blare day and night.

She joined two other mothers and their children from Vinnytsia on the ride to Lviv, and the group planned to catch another train later in the day across the border. From there they would travel to the Polish city of Lublin to stay with a host family and try to piece together the future.

“You feel everything – anger, panic, fear, sadness,” says Ms. Kopil, gray scarf wrapped around her neck against the winter cold. Her son giggles as he runs in circles nearby. In a murmur, she shares that her husband, a member of the country’s territorial defense force, stayed behind in Vinnytsia. “We do not know when we will see each other again.”

Wrenching separations

Women and children account for most of the train passengers arriving in and moving on from Lviv. Under a declaration of martial law, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has required men ages 18 to 60 to remain in the country, seeking to fortify the country’s military.

Valeriy Zhylin escorted his teenage daughter, Maria, to Lviv from their village outside the city of Korosten, 40 miles south of Belarus, where Russian troops stationed along the border advanced into Ukraine last week.

“We hope that maybe in a week or two things will improve,” says Mr. Zhylin, a physical education instructor at a secondary school who has joined his village’s defense force. As Maria prepares to take a train to the Polish border town of Przemyśl, they turn toward each other and embrace. Their wordless grief gives way to tears.

Watching her climb aboard, he says, “I still cannot believe we are in this nightmare.”

Wrenching separations occur with each train departing for Poland. A group of people begs a conductor to board a car already packed with passengers. He relents after a time and allows several of them up the stairs before telling the others to wait for the next train due in four hours. He closes the door and brings his hands to his face as if in prayer, his eyes wet, his anguish apparent.

The discarded artifacts of innocents caught in the chaos of war lie scattered across the platform. Security guards gather the items – blankets, suitcases, backpacks – and stack them against a wall. An abandoned baby stroller stands beside the tracks as a train begins rumbling westward.

The Russian invasion has destroyed daily routines and long-sought dreams. Days before Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered troops across the border, Natalia Tkachenko received a notice of approval for a visa to move to the United States.

She intended to join her husband in Texas later in March. But her final appointment to obtain the visa was scheduled for this week. So on Tuesday, Ms. Tkachenko, a lab technician in the eastern city of Dnipro, stands beside a train headed to Poland, along with her two sisters and their five children.

“Now everything has changed,” she says, clutching her passport and bringing a hand to her forehead. “I am terrified. I have no answers.”

A deep solidarity

The city of Lviv has rallied to the cause of aiding refugees passing through to Poland and other countries. Volunteers hand out sandwiches, bottled water, and blankets to the mass of travelers inside the train station. Blue tents set up outside by the fire and police departments provide space for people to stay warm and charge mobile devices.

Ivan Slotylo and Renata Kukul, a husband and wife who live in Lviv, showed up at the station in the morning to help distribute food and information to their exhausted fellow Ukrainians. Mr. Slotylo, a web designer, explains that while the war has spared the country’s western region for the most part, residents here feel a deep solidarity with those forced to flee home.

“Putin didn’t just attack some of us. He attacked all of us,” Mr. Slotylo says. “Our country needs us.”

A few blocks from the train station, in an art gallery complex converted into a collection center for donated goods, volunteers organize care packages with canned goods, toilet paper, water, and other essential items. They send the packages to villages and military units in the region as the commercial supply chain falls apart.

Yuri Popovych, a volunteer coordinator at the site and the owner of a software development firm, relates that the hub started operating three hours after Russia invaded Ukraine. He chokes up describing why he participates in the effort.

“This is a war that will leave scars on the souls of our people for generations,” he says. “You can’t just do nothing.”

A broader sense of cooperation has spread across the European Union in response to the war. A proposal to extend temporary asylum for up to three years to Ukrainian refugees entering the union’s 27 member countries appears headed toward approval this week.

The prospect of a warm welcome elsewhere in Europe offers a measure of solace to Nastia Grebenkova. The university student traveled alone across the length of the country this week, arriving by train in Lviv after a 27-hour journey from the northeastern city of Sumy, where she studies ecology.

Ms. Grebenkova, who wears a gray knit cap the color of her dyed hair, escaped as Sumy endured heavy shelling by Russian forces. Waiting to board a train to Przemyśl, she admits that her outward calm conceals a fear that she will never again set foot in her homeland.

“I am 18 years old,” she says, “and I worry I am now without a country.”

A new Iron Curtain?

Can we call the divide between Russia and the West a new Iron Curtain? Our reporter examines the historical origins and the value of the imagery in explaining events today.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

It was a chilling declaration. The noise of Russia’s assault on Ukraine “is the sound of a new iron curtain which has come down,” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said on Feb. 24 as Russian forces besieged his country.

The brutal Russian invasion and the tough economic and political steps the United States and its allies have taken in response have defined a new conflict that seems all too reminiscent of the worst periods of the Cold War struggle of which Winston Churchill warned when he coined the phrase “Iron Curtain” 76 years ago.

“There’s no question that we will see a remilitarized and divided Europe,” says Charles Kupchan, a Georgetown professor and Obama-era National Security Council official. Still that “iron” part of the curtain is probably not coming back. The world is unlikely to divide again into fragmented, independent geographical blocs. “There is a kind of irreversible element to globalization that will make a new Cold War feel and taste differently from Cold War 1.0,” Professor Kupchan adds.

In the end, the phrase “Iron Curtain” is an image meant to help illuminate the implications of an act of brutal Russian aggression that many Westerners find inexplicable. The events that have cast a shadow across Europe in early 2022 are very different than those that drove Western geopolitics in the Cold War era. But in a short period of time they have profoundly changed the way the United States and its allies think about Europe.

A new Iron Curtain?

Winston Churchill was out of power in March 1946. He’d lost a general election seven months earlier. But he was eager for a forum to expound his views on the developing post-World War II world, so he accepted an invitation to speak at tiny, out-of-the-way Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri.

A note scribbled at the bottom of the invitation sold the famous former British prime minister on the unlikely venue. “This is a wonderful school in my home state. If you come, I will introduce you,” wrote U.S. President Harry Truman.

With Truman in attendance Churchill delivered one of his most famous speeches, warning that in Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union was shaping many governments in its image and drawing them under its influence. The nations of the West, though tired of war, might have a new conflict on their hands.

“From Stettin in the Baltic, to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent,” Churchill said.

Last week, 76 years after the famous former British prime minister defined the geography of the Cold War with that iconic phrase, another Western leader invoked it to describe what was happening to his country.

The noise of Russia’s assault on Ukraine “is the sound of a new iron curtain which has come down,” said Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy on Feb. 24. His embattled country, he said, would do all it could to try and remain outside that barrier.

Whatever happens in Ukraine now, the geopolitics of the Western world have been profoundly changed by recent events. The brutal Russian invasion and the tough economic and political steps the United States and its allies have taken in response have defined a new conflict that seems all too reminiscent of the worst periods of the Cold War struggle of which Churchill warned.

Is Russia really trying to erect a new iron curtain, with its satellites on one side and what the press used to call the free world on the other? In some ways, that metaphor doesn’t exactly hold, say historians and scholars of international relations. In today’s interdependent world the kind of separation that iron curtain implies won’t be possible. But in some ways the old phrase remains apt.

“The analogy of the iron curtain proves useful in that it reminds us of the many unresolved legacies of the Cold War that animate [President Vladimir] Putin’s sense of grievance about Russia’s loss of status in the world,” writes Pamela Ballinger, professor of history at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “It also mobilizes the language of freedom versus tyranny so central to the Cold War struggle, a language that resonates in the heroic efforts of everyday Ukrainians to defend their homeland.”

Cold War 2.0

Whatever the outcome of the Russian attack on Ukraine, it will draw a scar across the middle of Europe, with a revanchist Moscow on one side and an Atlantic alliance on the other reenergized by Putin’s authoritarian military threat.

This new iron curtain will start at Russia’s long border with Finland in the north, then run down past the Baltic States, jog southwest around Belarus, and turn southeast again to pass through some as yet undetermined route toward the Black Sea.

“There’s no question that we will see a remilitarized and divided Europe,” says Charles Kupchan, a professor at Georgetown University and former senior director for European affairs on the National Security Council during the Obama administration.

President Putin appears to be trying to re-create a sphere of influence that will resemble the USSR, says Professor Kupchan. That’s evident in Moscow’s actions in former Soviet republics such as Georgia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan, as well as Ukraine, he says.

During the Cold War, the Iron Curtain was a hard barrier, symbolized by the barbed wire and guard towers of the Berlin Wall. To NATO allies, it seemed mostly intended to keep the populations of Eastern Europe and the USSR inside, and Western influence out.

That “iron” part of the curtain is probably not coming back. The world is unlikely to divide again into fragmented, independent geographical blocs. Mr. Putin hasn’t prevented Russians from emigrating. Europe has relied on Russian gas for energy – though it’s trying to reduce that reliance in the wake of the Ukraine invasion. Russian diplomats are helping to renegotiate the Iran nuclear deal. Addressing climate change and nuclear arms control will require Russian participation.

“There is a kind of irreversible element to globalization that will make a new Cold War feel and taste differently from Cold War 1.0,” says Professor Kupchan.

Holes in the new Iron Curtain

Given what’s happening in the heart of Europe, there are multiple ways to think about the analogy of a new Iron Curtain, because the analogy has multiple meanings, adds Jessica Weeks, chair in diplomacy and international relations at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

One is territorial. Whatever happens, Mr. Putin’s new greater Russia will be much smaller than the old Soviet sphere of influence, Professor Weeks says.

Many of the former Warsaw Pact states are already in the European Union. Poland and the Baltic States – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – are members of NATO.

A second is informational. Kremlin censorship on the level of the Soviet era is no longer possible, but state-directed media still floods the Russian information zone, and the two sides of the new barrier will experience very different geopolitical narratives.

A third could be economic. The Soviet and the West traded very little during the Cold War, and now, due to Western sanctions, they may be separating again.

How deep the new economic division goes may be contingent on the outcome of the Ukraine invasion. The Russian people might find it difficult to accept a deep plunge in their standard of living. But punitive Western sanctions could thrust Russia back into a period of relative autarky, where it is forced to adapt to relative economic self-sufficiency, says Emma Ashford, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Russia might still have some trade ties with the West, particularly in energy, but not in other sectors, says Ms. Ashford.

“The argument for some time now has been that trade and integration is a wonderful tool against conflict – and we are, I think, seeing the limits of that theory,” she says.

A “vortex of instability”

But there may be one way in which the analogy of a new Iron Curtain falling over Europe is not entirely accurate, and may even be unhelpful, says Michael Kimmage, a professor of Cold War history at Catholic University and a former member of the State Department’s policy planning staff in charge of the Russia/Ukraine portfolio.

The Iron Curtain metaphor worked during the Cold War years because the borders between blocs were clear and stable. The line was by no means straight – it zigged through the middle of Germany, dividing it into East and West – and it had neutral buffer zones such as Finland. But the divisions were so set that the West and East agreed to them in the 1975 Helsinki Final Act, says Professor Kimmage.

In contrast the Russian invasion of Ukraine has ripped a hole in European border stability. No one knows how much of Ukraine Mr. Putin wants to take, and how long he wants to hold it. No one knows if the conflict might spread, perhaps to Poland or the Baltics. No one knows whether other regional players, such as Turkey, will become more assertive in response.

“You have a very uncertain, fluid zone of contestation between the two hostile parties. In that sense, there really is nothing like an Iron Curtain,” says Professor Kimmage.

Instead there is what he calls a “vortex of instability.”

Following World War II, Soviet leader Josef Stalin at least had a discernible reason behind the Soviet push for an Eastern European sphere of influence. Given the state of the world at the time, he wanted a buffer between the USSR and Germany.

In contrast Mr. Putin has done something less coherent and less likely to succeed, says Professor Kimmage. In the absence of provocation from Ukraine, he has invaded the country with no immediate security pretext.

Russia has the largest conventional army in Europe, plus nuclear weapons. That ensures it will be able to press forward in Ukraine, even if the invasion has not gone as Moscow expected so far. The Biden administration and other Western governments have done well organizing their response of sanctions but they will have to set clear goals for that approach, according to Professor Kimmage.

“We have to continue to contend with a country that has many different levers of influence, and we’ll just have to think about what that all means in light of this terrible war,” he says.

A lengthening shadow

In the end the phrase “Iron Curtain” is just an image meant to help illuminate the implications of an act of brutal Russian aggression that many Westerners find inexplicable. The events that have cast a shadow across Europe in early 2022 are very different than those that drove Western geopolitics in the Cold War era. But in a short period of time they have profoundly changed the way the U.S. and its allies think about Europe.

“It’s certainly the case that we’ve got more of a clear dividing line now than we did two weeks ago between the West and Russia in both political and economic terms,” says Chris Miller, co-director of the Russia and Eurasia Program at Tufts University’s Fletcher School.

On Ukraine, Congress rediscovers bipartisan spirit

We are in a rare moment of U.S. political bipartisanship. Our reporter looks at why members of Congress are united in finding ways to help Ukraine.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

With the security crisis in Europe suddenly eclipsing the bitter domestic policy battles of the past year, Washington lawmakers are flexing a muscle some feared had all but atrophied: bipartisan unity.

Congress has moved swiftly to authorize weapons transfers to Ukraine and is scrambling to authorize additional assistance through its budget. On Wednesday, the House was scheduled to consider a resolution supporting the people of Ukraine, while in the Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer promised to move forward with a bipartisan military and aid package.

During President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address last night, Republicans rose en masse with Democrats in multiple standing ovations, with the yellow and blue of the Ukrainian flag splashed across ties, scarves, and lapel pins.

In the coming days, that bipartisanship will be tested as Russian troops continue their advance, forcing Mr. Biden to translate lofty ideals into concrete actions that will almost certainly come with mounting tradeoffs.

But for now, both sides seem committed to presenting a united front. Asked if he thought members of Congress put on a convincing show of American unity last night, GOP Sen. Rob Portman responded in the affirmative.

“I really do,” he said. “The response was encouraging.”

On Ukraine, Congress rediscovers bipartisan spirit

With the security crisis in Europe suddenly eclipsing the bitter domestic policy battles of the past year, Washington lawmakers are flexing a muscle that some feared had completely atrophied: bipartisan unity.

Congress has moved swiftly to authorize weapons transfers to Ukraine and is scrambling to authorize additional military and humanitarian assistance before a March 11 budget deadline. Anti-aircraft and anti-tank missiles funded by Congress have been crucial in enabling Ukrainian forces to slow Russia’s invasion.

“It’s no secret they need more help ... they need it yesterday,” said Democratic Sen. Chris Murphy of Connecticut Monday night after meeting with Ukrainian Ambassador Oksana Markarova. “This is a moment for us to put aside our differences.”

During President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address last night, Republicans rose en masse with their Democratic colleagues in multiple standing ovations for Ukraine, with the yellow and blue of the Ukrainian flag splashed across ties, scarves, lapel pins, and flags. Just minutes into the speech, the whole chamber rose in fervent applause for Ambassador Markarova, expressing support for her country’s determination in fighting back against a much better equipped invading army.

“We the United States of America stand with the Ukrainian people,” said Mr. Biden, whose administration has levied sanctions on Russian oligarchs and cut off some Russian banks from the international SWIFT system, while green-lighting weapons deliveries to the Ukrainian military and seeking an additional $6.4 billion from Congress for additional weapons and humanitarian assistance. “We are inflicting pain on Russia and supporting the people of Ukraine.”

Major foreign policy crises like this one typically generate a “rally ’round the flag” effect, even in a body as divided as Congress. Still, this isn’t the return of 9/11. The rallying is around Ukraine more than Mr. Biden. In the coming days, the depth and breadth of that bipartisan unity will likely be tested as Russian troops continue their advance, forcing the president to translate the lofty ideals of Tuesday night’s speech into concrete actions that will almost certainly come with mounting tradeoffs.

Already, Republicans are criticizing the administration’s climate change policies as clashing with a need for energy independence. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s nuclear threats and territorial ambitions could also compel tough decisions about how to deploy U.S. military and other resources.

And notably, even as GOP leaders have offered strong support for the Biden administration’s moves to assist Ukraine, they haven’t refrained from criticizing the “weakness” they say precipitated the crisis. Democrats, for their part, say the real weakness came during the Trump years. The former president threatened to withdraw from NATO if members didn’t pay their dues and held up $391 million in military funding for Ukraine that had been approved by Congress. Mr. Trump later transferred the funds but was impeached for “corruptly soliciting” Ukraine to investigate his opponent, Mr. Biden.

For now, however, both sides seem committed to presenting a united front. During the roughly hour-long speech, there were only a few jeers from Republicans. To be sure, they stayed seated during bursts of Democratic applause for proposals to address issues like high prescription drug costs and corporate tax evasion. But even his staunchest critics stood to cheer lines about keeping schools open, appointing a chief of pandemic fraud, securing the border, and funding – not defunding – the police.

The Kremlin has long sought to amplify and exploit U.S. partisan divides, weakening trust in government and democratic systems. Analysts say the increasing vitriol between Democrats and Republicans has played into Mr. Putin’s hands as he sought to discredit American democracy and challenge the global order it spearheaded after World War II.

Asked if he thought members of Congress put on a convincing show of American unity last night, Ohio Sen. Rob Portman, whose state is home to one of the country’s largest Ukrainian populations, responded in the affirmative.

“Yes, I do, I really do,” said the Republican co-chair of the Senate Ukraine Caucus. “The response was encouraging.”

“We’re really coming together”

Dressed in the colors of the Ukrainian flag, GOP Rep. Victoria Spartz of Indiana stepped up to the microphone Tuesday to answer a reporter’s question about her grandmother back in Ukraine.

“My grandma is 95, she experienced Stalin, she experienced Hitler,” said the native-born Ukrainian, after an emotional speech calling on President Biden to take stronger action. “But, she says, she has never experienced something like that, ever.”

Hours before President Biden was scheduled to give his prime-time address, Ms. Spartz and her Republican colleagues criticized him in a press conference for everything from not heeding warnings about the need to build up Ukraine’s defenses to administration policies they say have contributed to inflation, including at the gas pump.

Texas Rep. Michael McCaul, who also spoke, said in a follow-up hallway interview that it took months to transfer $200 million worth of weapons to Ukraine after the funding was approved. He’s headed to Poland this weekend to figure out how to get an additional $350 million worth of weapons into the country now that Russian troops have moved in, complicating the logistics.

“The time to have done this was before,” says Representative McCaul, the top Republican on the House Foreign Affairs Committee. “The reality is, our foreign adversaries are emboldened, they’re empowered, and they sense weakness. And projecting weakness always invites aggression.”

Still, he too emphasized the importance of domestic unity in the face of such aggression.

“I think on my side of the aisle we’re really coming together on this,” he said ahead of Tuesday night’s speech. “I don’t want Putin to see a divided Congress because I think that weakens our strength.”

Divisions over energy policy

In the eyes of many Republicans, Mr. Biden’s hands are partly tied in this crisis by America’s dependence on foreign sources of energy – something they blame on the administration’s pivot away from domestic oil and gas production as part of its efforts to curb climate change. U.S. dependence on Russian oil imports has spiked over the past year. Meanwhile, the price of oil has gone from $60 a barrel to more $100. So far, U.S. sanctions on Russia do not apply to its energy sector, a key driver of its economy.

“Putin is bankrolling his war effort because of American people who are paying $1 more a gallon for gas than they were when Biden came in office,” said GOP Sen. John Barrasso of Wyoming, the top Republican on the Senate’s Energy and Natural Resources committee.

Mr. Biden sought to assure Americans that he would do his best to limit the pain at the gas pump, announcing that his administration had worked with other countries to release 60 million barrels of oil from strategic reserves – a little under two weeks’ worth of Russian oil exports. The price of U.S. crude oil continued to rise after his announcement, hitting a 14-year peak of $116 before easing somewhat on Thursday amid hopes of a deal with Iran.

Senator Barrasso and his GOP colleagues would like Mr. Biden to do more. In a letter Wednesday they urged the president to take immediate action on 10 points that would boost America’s energy independence and blunt Russia’s ability to hold other countries hostage to its oil and natural gas. “Mr. President, America is the world’s energy superpower,” they wrote. “It is time we started acting like it again.”

Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina said at a press conference that there was bipartisan support for a host of measures, including sanctions, weapons, fuel, and uniforms. “There is no bipartisanship on the energy side,” he added, urging the president to sanction Russia’s oil and gas industry, calling it Mr. Putin’s Achilles heel. “Never in the history of warfare have we had a chance to deliver such a decisive blow without firing a shot. Let’s deliver that blow.”

On Wednesday, the House overwhelmingly passed a resolution, 426-3, supporting the people of Ukraine and calling for an immediate Russian withdrawal. “The gravity of this moment calls for Congress to speak with one voice,” said House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy in a statement.

Meanwhile in the Senate, Majority Leader Chuck Schumer promised to move forward with a bipartisan military and aid package.

“Nothing would make Putin happier than having Democrats and Republicans divided,” he said.

Editor's note: This story was updated to reflect the announced release of strategic oil reserves and the trend in U.S. crude oil prices.

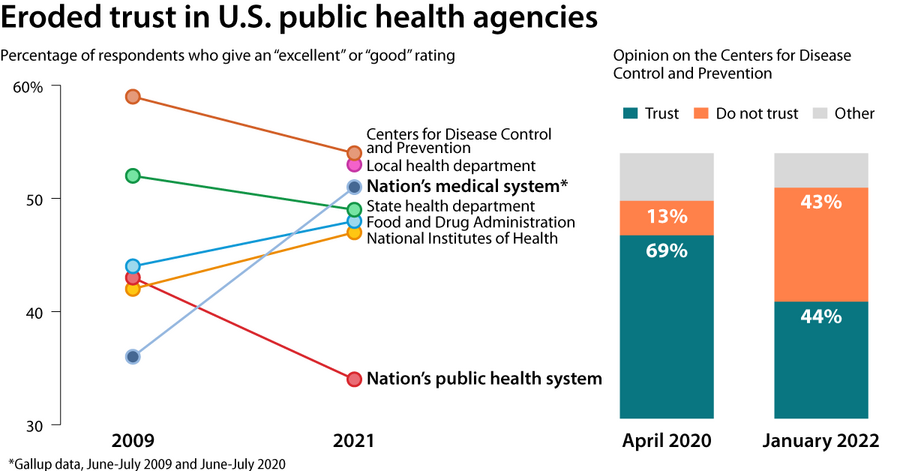

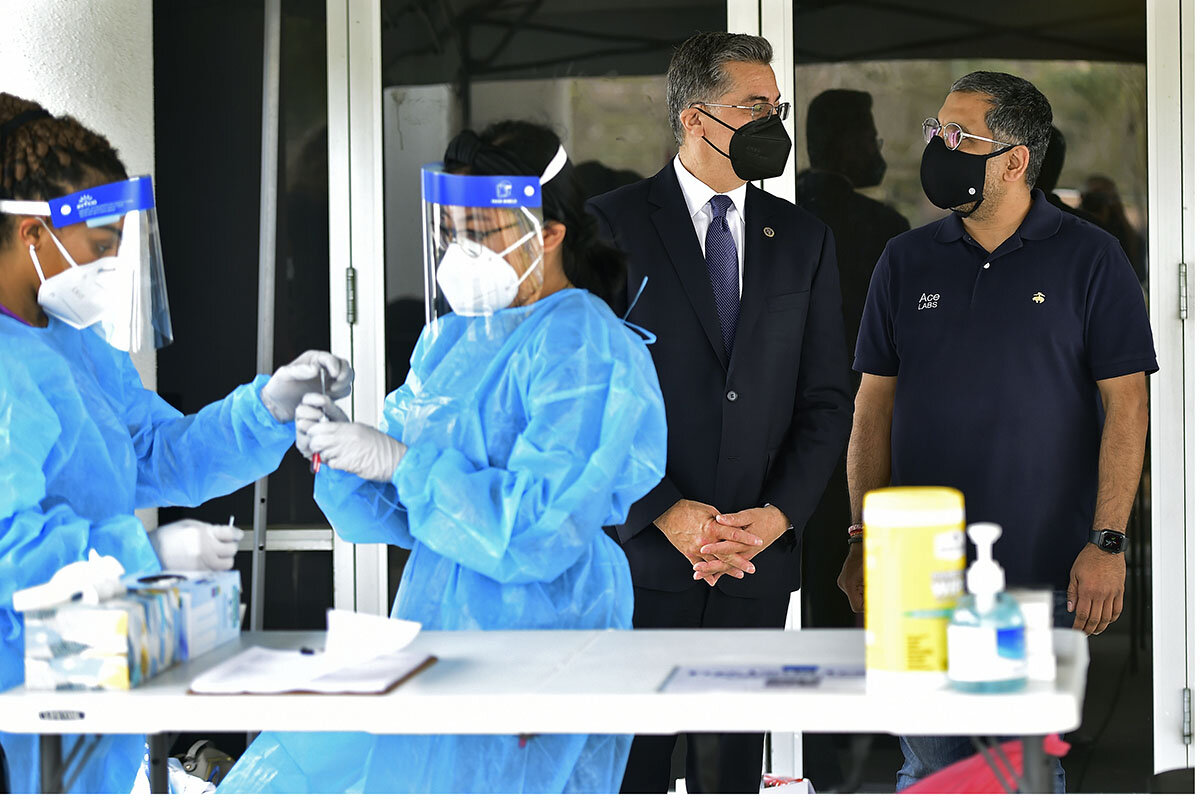

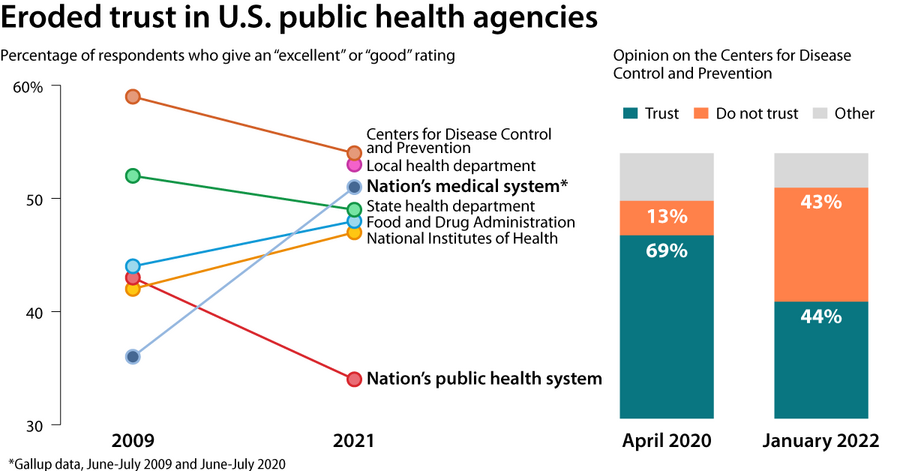

CDC has lost public trust: Can that be fixed?

The pandemic exposed many problems with the U.S. public health system, especially the federal agencies. Our reporter looks at how trust in that system might be rebuilt.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The pandemic has revealed what experts say are deep shortcomings in America’s public health system. Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on topics from masking to isolation has been consistently confusing. Even now, sought-after COVID-19 test kits and public health data either arrive late or don’t arrive at all. Some local public health departments still send data through snail mail or fax machines.

Implementing fixes will be difficult, but the agencies and Congress are increasingly motivated to start. Core to the challenge: America’s public health system is sprawling, hard to coordinate, and recovering from decades of underinvestment. But many experts say better communication with the public is an important, and feasible, place to start.

On Wednesday, the Biden administration released a new 96-page pandemic plan tailored to a return to more normal life. In a briefing with reporters, White House and public health officials announced increased access to treatments and vaccines, updated systems to monitor the virus, and closer coordination with state and local partners.

The document itself starts more simply. Goal No. 1, it says, is: “Restore trust with the American people.”

CDC has lost public trust: Can that be fixed?

Falling COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations are pushing America toward the most hopeful phase of this pandemic in months. But America’s public health agencies – responsible for keeping those numbers low – may be at their weakest point in years.

In January, the Government Accountability Office added the Department of Health and Human Services to its High Risk List for “federal programs and operations that are vulnerable to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement, or need transformation.”

And trust in agencies that HHS oversees – the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – has plummeted, based on polling now versus the dawn of the pandemic in 2020.

Americans consistently report low trust in government. With public health, the challenges were magnified early in the pandemic as President Donald Trump disagreed with or undercut agency officials.

But problems have persisted over the past year even under a new president. The trust deficits are in part a performance review – with evidence to back it up.

CDC guidance on topics from masking to isolation has been consistently confusing. The administration and FDA advisory committee publicly disagreed about the need for booster shots last fall, slowing their rollout. Even now, sought-after COVID-19 test kits and public health data either arrive late or don’t arrive at all. Some local public health departments still send data through snail mail or fax machines.

Polling by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Polling by NBC News

Fixing American public health will be difficult, but the agencies and Congress are increasingly motivated to start. Core to the challenge: America’s public health system is sprawling, hard to coordinate, and recovering from decades of underinvestment. Add in the patchwork interplay of state and local governments, and the system currently is not set up to succeed in a crisis, says Thomas Bollyky, director of the global health program at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“Governments can really only protect their citizens by convincing them to take measures to protect themselves,” Mr. Bollyky says. “Especially in free societies, the success of those efforts depends on trust between citizens and their governments as well as among citizens themselves.”

Some of Mr. Bollyky’s research has found that countries with higher levels of trust in government and other people had lower infection rates. The logic: If people believe their government’s advice is reliable and that other people will follow it, the more likely they are to follow it too.

“A real opportunity”

In fact, as a bipartisan effort in Congress seeks to address some of those structural problems, there are things the CDC, FDA, and other agencies can fix on their own – above all communication. Starting with those, says Tom Frieden, CDC director from 2009 to 2017, is the first step.

“As we enter a new phase here, with better tools than we’ve ever had ... I think we do have a real opportunity to see significant improvements in our response and significant increases in the public’s willingness to listen,” says Dr. Frieden.

On Wednesday, the Biden administration released a new 96-page pandemic plan tailored to a return to more normal life. In a briefing with reporters, White House and public health officials announced increased access to and reserves of masks, treatments, and vaccines; updated systems to monitor the virus; and closer coordination with state and local partners.

The document itself starts more simply. Goal No. 1, it says, is: “Restore trust with the American people.”

But in America, getting people to listen to public health authorities can be particularly difficult, says Robert Blendon, an emeritus professor of health policy and political analysis at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The public doesn’t tend to trust the government or scientists, has little scientific education, and often approaches the virus politically, he says.

Declining funds

Some of the issues stem from things the department’s agencies can’t control, particularly underinvestment. In the past 20 years, as 9/11 and the Great Recession pushed funds elsewhere, public health funding has withered. The budget for the CDC’s Public Health Emergency Preparedness agreements that aid lower-level health departments, for example, fell from $940 million in 2002 to $675 million in 2020. Since the financial crisis, tens of thousands of public health jobs have disappeared.

While funding has risen by about $55 billion since the pandemic began, it’s almost impossible to rebuild an agency in the middle of a crisis. Existing employees are already doing too much work, often with low morale and subpar tools.

“In an age in which everybody has a cellphone ... the public health system is still using fax machines, still filling out papers with pen and ink, and struggling to send information across the street,” says Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association.

That slows down vital data as reports are logged by hand, often resigning policymakers to imperfect decisions based on imperfect information. Local, private, and federal data don’t always sync, especially because the United States, unlike other countries, doesn’t issue a single identifier for each patient.

But the CDC’s issues aren’t just delayed data or medical uncertainty, many experts say. The agency’s communication has been a near-constant issue, from the government’s initial advice not to wear masks to the opaque CDC guidance on isolation during the omicron wave.

“The irony here is that the CDC literally wrote the book on how to communicate in a health emergency,” says Dr. Frieden, the former CDC director. “Be first. Be right. Be credible. Give people concrete, practical, proven things to do to protect themselves and their family.”

Speaking to the nonscientists

Scientists have a tendency to communicate like they’re speaking to other scientists, says Lisa Lee, a former 14-year CDC employee and executive director of the Presidential Bioethics Commission under the Obama administration. That approach doesn’t work for a public that generally doesn’t understand scientific uncertainty or the information that motivates public health decisions, she says. Americans need government agencies to show their work when they give new guidance.

It also might start with a shift in scenery. In past health emergencies, briefings used to be held at the CDC’s Atlanta headquarters. They’re now based in the White House.

“There is a history in crisis response and pandemics, in particular, of building trust in that response even in low-trust environments,” says Mr. Bollyky. “We just simply didn’t follow that guidance in the context of this pandemic.”

At the FDA, the biggest problem may be the appearance or risk of conflicted interests, says David Gortler, a former senior adviser to the FDA commissioner. Commissioners and high-level staff regularly leave public service for jobs at the drug companies they once regulated.

“The FDA is not a transparent organization,” adds Dr. Gortler, now a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington. “People hate the FDA because they don’t understand what they do.”

Efforts rising in Congress

What is understood is that America’s public health institutions need reform.

In January in the Senate, Democrat Patty Murray of Washington and Republican Richard Burr of North Carolina introduced the PREVENT Pandemics Act, which among other things would fortify public health supply chains, improve agency coordination and data systems, and create a bipartisan task force to review the nation’s COVID-19 response.

That structural reform is necessary, says Celine Gounder, an infectious disease specialist at New York University and a member of the Biden-Harris COVID-19 transition team. But until it arrives, the CDC and other agencies can use existing tools to improve the pandemic response and trust in it. In 2015, she spent months in West Africa working to contain Ebola, an effort that started poorly too. Small things – like using black body bags rather than white ones – lowered public trust and cooperation. But they didn’t know that until they started studying the local culture and addressing local needs.

“There’s a sort of American exceptionalism, where we think we’re somehow different, better, and more sophisticated,” says Dr. Gounder.

Yet the U.S. has consistently experienced similar problems, with the public approaching the virus with different values. Many Americans have been concerned about the pandemic’s spillover impacts on the economy, mental health, and education. Those people shouldn’t be ignored, says Dr. Gounder. They need messages and messengers that speak to them, and they need a stronger social safety net during crisis. The country has low levels of trust, she says, but that doesn’t mean people reflexively fight public health. Hesitancy isn’t the same as resistance.

“You need to address these other concerns effectively,” says Dr. Gounder. “Otherwise, you are going to have that ... backlash.”

Polling by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Polling by NBC News

Essay

To skate, you must learn to get up again

We have a moving personal essay by a young woman who struggled with the burden of expectations – parental and her own – and how a father’s love helped lift that burden.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Born and raised in Beijing, I began skating when I was 8 years old. The first time I stepped onto the ice, I glided cautiously, trying not to fall. “Be bold!” my father shouted to me. “Take a bigger step!”

But when I did so, I fell – again and again at first. I spent my free time at the rink, endlessly practicing. Two years later, I’d had enough. The pressure was too much.

For the next 10 years, I didn’t skate at all. But when I returned to Beijing in 2019 over college winter break, I came across a new pair of figure skates my dad had bought for me. “I figured you’d wear them eventually,” he said. That thought had never occurred to me. Still, I brought the skates back with me.

This winter, inspired by the Olympics, I put on skates again. I carefully stepped onto the ice at a Boston rink. This time, skating felt the way it had when I first fell in love with it. I glided and danced. I was unpressured, free, joyful.

To learn to skate, one must get up after a fall. I’d fallen 10 years ago, and now I had gotten up again.

“Be bold!” I hear my father calling. “Take a bigger step!”

To skate, you must learn to get up again

My roommate and I sat very still and held our breath to watch the showdown between ice skaters Yuzuru Hanyu of Japan and Nathan Chen of the United States, as though our twitching or breathing might interfere with their programs at the Beijing Winter Olympics. But when Mr. Chen launched himself into the air, it wasn’t his quadruple flip that caught my eye – it was the empty seats in the upper deck behind him.

They looked familiar. And then I realized that the competition was being held in Beijing’s Capital Indoor Stadium. Those seats were where my parents had stood, my dad holding a video camera to record my daily practice sessions so we could review every twirl and spiral.

Born and raised in Beijing, I began skating when I was 8 years old. I remember the first time I stepped onto that rink; I glided forward cautiously, my toes pointed inward to keep me from falling.

“Be bold!” my father shouted to me from that balcony. “Take a bigger step!” His stentorian voice echoed through the arena.

But as soon as I tried to do so, I lost my balance and fell – again and again. This is way harder than it appears, I recall thinking.

I’d seen Chinese pair skaters Shen Xue and Zhao Hongbo’s bronze medal-winning performance at the 2006 Winter Games in Turin, Italy. They inspired a wave of national pride and made figure skating a mainstream sport in China.

I joined the rush. Even as a young girl, I saw skating not only as a sport that combines athleticism and aesthetics, but also as my ticket to a top Beijing middle school. Even though my coach told me I’d started skating too late to get into elite competition, I was convinced that one day I would be just like the skaters I saw on TV.

The “kiss and cry” area for skaters at the Beijing Winter Olympics was where a broad hallway had been. Then, it was a place crowded with kids like me and their parents. The young skaters would be warming up before practice while their parents anxiously hoped their child would somehow rise to the top.

I spent most of my time outside school at the rink. There, my skating friends and I would laugh during our skating-backward races. There, too, I held back tears when my coach yelled at me for poor footwork. It’s where I stayed after my lessons to endlessly practice spirals and toe loop jumps.

Then one day, two intense years later, I’d had enough. The pressure was too much. I told my parents I couldn’t do it anymore.

Thankfully, my loving father and mother understood. They let me stop. But even after I quit, guilt and pressure stayed with me. My parents had sacrificed so much for me, and I felt I’d failed their expectations. I also felt I’d lost part of my identity; skating had set me apart. Could I hope to be considered for a top-notch school without it? I’d often had self-doubts, and this made it worse.

My fear of not getting into a competitive middle school was unfounded. For the next 10 years, though, I didn’t hear the grinding sounds of my skates biting into the ice. My after-school hours were packed with math and English tutoring. I started a new athletic endeavor – cross-country running – that I still pursue today. Most important, I was no longer forcing myself to do something that I didn’t feel in my heart.

Even so, I still enjoyed watching figure skating on TV from time to time. I admired the skaters’ hard work and achievement. They were living the dream I used to have.

Right before the pandemic lockdowns began, I returned home to Beijing over winter break from college in the U.S. In my closet I was surprised to find a shiny new pair of figure skates my dad had bought for me. The blades had been freshly sharpened.

“I figured you’d wear them eventually,” he said, confidently. “It’s just a matter of time.”

I shook my head. That thought had never crossed my mind. Still, I brought the skates back with me to Boston.

This winter, inspired by the Beijing Olympics, I put on skates again, the skates my father had bought for me. I carefully stepped onto the ice at a Boston rink. And this time, skating felt the way it had when I fell in love with it for the first time. I glided and danced on the ice, feeling free and joyful. I was skating without pressure, without winning or losing.

To learn to skate, one must get up after a fall. One cannot learn without falling sometimes – or often. I did fall again, but 10 years later I’ve finally gotten up again. I hear the echo of my father’s exhortation to me as a little girl:

“Be bold! Take a bigger step!”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The help-a-refugee way to save Ukraine

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One video that’s gone viral out of Ukraine shows volunteers on a train giving food to university students of various countries trying to reach the Polish border. Some 76,000 students from 155 nations were in Ukraine when Russia attacked Feb. 24. They, like nearly 1 million Ukrainians, have fled a war that is more than a clash of armies.

The act of generosity toward the non-Ukrainian refugees is a reminder of why so many countries oppose this war. Certain values such as individual rights are globally embraced. They are not tied to a specific culture or “civilization.” On the other hand, President Vladimir Putin says “Russia is not just a country, but a distinct civilization,” one that includes Ukraine. For him, Ukraine’s drift toward the European Union must be stopped.

The EU’s 27 member states have united like never before in preparing for a flow of refugees from Ukraine. The people who remain in Ukraine to fight Russian forces, says Ursula von der Leyen, president of the EU’s executive arm, are “fighting for universal values.”

There’s nothing more universal than strangers feeding other strangers in a crisis, just like those desperate students on the train to Poland.

The help-a-refugee way to save Ukraine

One video that’s gone viral out of Ukraine shows volunteers on a train giving food to university students of various countries trying to reach the Polish border. Some 76,000 students from 155 nations were in Ukraine when Russia attacked Feb. 24. They, like nearly 1 million Ukrainians, have fled a war that is more than a clash of armies or the preservation of an independent nation.

The act of generosity toward the non-Ukrainian refugees is a reminder of why so many countries oppose this war. Certain values such as individual rights are globally embraced and rooted in principles made practical anywhere. They are not tied to a specific culture or “civilization.”

On the other hand, President Vladimir Putin says “Russia is not just a country, but a distinct civilization,” one that includes Ukraine and many other Slavic peoples. For him, Ukraine’s drift toward the European Union’s project of implementing universal values must be stopped.

As the war escalates, the EU is rushing to help innocent civilians from Ukraine who are pouring into the border states of Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Moldova, and Romania. In Romania, for example, 175 Egyptian students who fled Ukraine were airlifted to Cairo this week. Moldova aided the evacuation of nearly 1,000 Chinese students. Polish soldiers helped nearly 150 Zambian students reach the Warsaw airport. In the United States, a Texas-based nonprofit, Sewa International, has launched a help line to evacuate international students stranded in Ukraine.

The EU’s 27 member states have united like never before in preparing for a flow of refugees from Ukraine. “We must show the power that lies in our democracies,” says Ursula von der Leyen, president of the EU’s executive arm. “We must show the power of people that choose their independent paths, freely and democratically. This is our show of force.”

The people who remain in Ukraine to fight Russian forces, adds Ms. von der Leyen, are “also fighting for universal values and they are willing to die for them.”

There’s nothing more universal than strangers feeding other strangers in a crisis, just like those desperate students on the train to Poland.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Harmonious resolution after a phishing scam

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Ingrid Peschke

The power of God, divine Truth and Love, is always present to inspire wisdom, peace of mind, and solutions, as a woman experienced after money was fraudulently withdrawn from her family’s checking account.

Harmonious resolution after a phishing scam

Cybersecurity has been a pressing issue for some years now, on both an individual and a global level. Scammers are looking for a moment when you let your guard down and, bam, they’ve caught you.

I know because one night my husband discovered a large sum of money had been fraudulently deducted from our checking account to pay a bill that wasn’t ours. He recalled an email he’d received earlier and recognized that this incident was the result of a phishing scam. We explained this to our bank, but they couldn’t refund the money without further investigation.

The situation left us feeling violated and uncertain about how we’d cover this unexpected, potentially long-term deficit. This was further complicated since we were in the middle of an extensive house project, which we had committed to completing with our contractor. After we took practical steps to secure our account, I reached out to God for peace.

When an injustice occurs, it can be so tempting to place blame and feel animosity toward the perpetrators. Yet I knew these reactions have nothing to do with our true nature as the expression of God, who is Love itself and loves all equally. I knew that harboring feelings of hurt and anger wouldn’t help me move past this event or see the blessings that God always has in store for His children.

I thought more about the meaning and source of true security and reliability. It seemed so unjust to me that someone out there had seen our private information and manipulated our account without our knowledge. So I thought about what can never be violated and is always safe: our relation to God, the Father-Mother that lovingly cares for all.

One of my go-to passages for inspiration and comfort is this one from Psalms, which I memorized as a young student in the Christian Science Sunday School: “He that dwelleth in the secret place of the most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty. I will say of the Lord, He is my refuge and my fortress: my God; in him will I trust. Surely he shall deliver thee from the snare of the fowler, and from the noisome pestilence” (91:1-3).

Over the years, this psalm has helped me to lean on and trust in God’s power and protection, which is spiritual and inviolable, not dependent on a material source. In this case it also reminded me that no phishing trap is more powerful than God, who knows only good and whose pure goodness is always at hand to deliver us from any harm or apparent negligence.

I had also been studying that week’s Christian Science Bible Lesson, which happened to include the following description of “purse” from the Glossary of biblical terms found in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy: “Laying up treasures in matter; error” (p. 593).

Material treasures may be subject to theft and loss, but true treasure has its source in God, divine Spirit. As such it cannot truly be harmed or stolen at any time. The supply God gives us is permanent. As this line from Scripture reassures us, “My God shall supply all your need according to his riches in glory by Christ Jesus” (Philippians 4:19).

I also prayed to know that justice is a quality of God, which encouraged me that the bank would uncover the dishonest transaction without harm to our financial situation. While it may seem that evil has temporary power, it has no legitimacy to produce harm, because God, good, is the one true all-power. Divine Truth naturally unveils wrong and restores justice. “Let Truth uncover and destroy error in God’s own way, and let human justice pattern the divine,” Mrs. Eddy urged us (Science and Health, p. 542).

These ideas helped me to hold on to my joy and confidence in God’s protection, even in the face of doubt and confusion.

As it turned out, the bank resolved our case and returned the funds much sooner than expected. We were able to fulfill all of our obligations in the meantime, including successfully completing our home project. We’ve become even more alert to suspicious emails. And I now have a firmer understanding of true security, with God as its abiding source.

Whether we’re facing a security issue firsthand or hearing about similar issues on a larger scale in the news, we can acknowledge the presence and power of divine Truth and pray to see “human justice pattern the divine.”

A message of love

Babe in arms

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’ll have more on Ukraine, and Hollywood’s latest take on Gotham City’s most famous purveyor of justice.