- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

When tragedy gives us hope

Ali Martin

Ali Martin

What is it that keeps us engaged in a tragedy, even when we know it’s going to end tragically?

Hope.

I had the joy of seeing “Hadestown” over the weekend. The Tony Award-winning musical tells the story of Orpheus and Eurydice through a framework of modern-day racism and socioeconomic injustice.

In the retelling of this Greek myth, the charmed Orpheus falls in love with Eurydice, who’s worn down by the Fates and falls under the pressures of bad choices into the underworld. Who hasn’t been there? Orpheus goes after her, reminds Hades and Persephone of their own lost love, inspires an uprising of the oppressed, and almost gets his happily ever after with Eurydice. So, so close.

Despite the anguish of his near miss, the musical ends on a high note. Because along the way, Orpheus made people believe in a better world – in a world they couldn’t see, but could feel in their hearts. And he inspired them to move toward that.

Aliyah Fraser is creating her better world in rural Ontario, where she combines social justice and environmental sustainability at Lucky Bug Farm. The Monitor’s Sara Miller Llana introduces us to Ms. Fraser and other Black farmers who are empowering their own underserved communities by growing and selling fresh produce.

And Monitor contributor Lydia Tomkiw takes us to Poland, where Ukrainian refugees are navigating the limbo of war, trying to envision the life they’ll have when the war finally ends.

Their stories tie together with hope, and acknowledge the strength that propels humanity forward even when chaos or catastrophe seem to have a stronger hold. Hope is a gift, but it’s also a talent.

Eurydice touches on that at the end of “Hadestown”:

“Some flowers bloom when the green grass grows.

My praise is not for them.

But the one who blooms in the bitter snow

I raise my cup to him.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

What overturning Roe could mean for US

For the first time in modern history, the U.S. Supreme Court appears on the verge of taking a right away. If a leaked opinion on abortion rights becomes the final ruling, it is a decision that is both unsurprising, and yet seismic in its consequences.

-

Henry Gass Staff writer

-

Harry Bruinius Staff writer

It’s just a draft, and may be different in its final form. But the leaked opinion suggesting the Supreme Court is on the verge of overturning Roe v. Wade could herald a sweeping change in U.S. law and domestic policy that would return the nation to an America not seen in 50 years.

It would be an America the Republican Party has long planned for, with a decadeslong strategy of shaping the nation’s highest court by confirming reliable conservative justices. And a reality that Democrats have feared and seen coming, as red states passed laws testing the limits of Roe protections as the Supreme Court bench tilted right.

And it would be an America full of difficult questions dealing with perhaps the hottest of U.S. hot-button political issues. Will the battle over abortion become more intense? How would Roe’s demise affect upcoming elections? Will either party be able to pass national legislation?

Perhaps most importantly, would overturning Roe mean other personal rights guaranteed by the federal government but not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution – such as same-sex marriage, access to contraception, even interracial marriage – be on shaky legal ground?

These questions are difficult in part because the situation is so unprecedented.

“It’s really hard to think of a situation where the court created a landmark constitutional right and then changed its mind,” says law professor Eric Segall.

What overturning Roe could mean for US

It’s just a draft, and may be different in its final form. But the leaked majority opinion suggesting the Supreme Court is on the verge of overturning Roe v. Wade could herald a sweeping change in American law and domestic policy that would return the nation to an America not seen in 50 years, with abortion rights determined by individual states.

It would be an America the Republican Party has wished and long planned for, with a long-term strategy of shaping the nation’s highest court by nominating and confirming reliable conservative justices. It would be a world Democrats have feared and seen coming, as red states passed laws testing the limits of Roe protections as the Supreme Court bench tilted right.

It would also be a world full of difficult, open questions dealing with perhaps the hottest of U.S. hot-button political issues. Will the battle over abortion become more intense, or cool down? How would Roe’s demise affect the midterm elections, and 2024? Will either party be able to pass national legislation codifying its abortion beliefs?

Perhaps most importantly, would overturning Roe’s protection of abortion mean that other personal rights guaranteed by the federal government but not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution – such as same-sex marriage, access to contraception, even interracial marriage – are on shaky legal ground as well?

These questions are difficult in part because the situation is so unprecedented.

“It’s really hard to think of a situation where the court created a landmark constitutional right and then changed its mind,” says Eric Segall, a professor of law at Georgia State University in Atlanta.

The draft opinion was leaked to Politico and published Monday evening. On Tuesday the Supreme Court confirmed that the draft, dated Feb. 10, is authentic, but added in a statement that “it does not represent a decision by the court or the final position of any member on the issues in the case.”

Source of outrage: The leak or the opinion?

Many Republicans focused on the leak of a Supreme Court work in progress, saying it was outrageous and calling for the leaker to be found and prosecuted. Chief Justice John Roberts announced Tuesday that he has asked the marshal of the court to open an investigation into the source of the leak.

“The Chief Justice must get to the bottom of it, and the Department of Justice must pursue criminal charges if applicable,” said Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky in a statement Tuesday.

Many Democrats decried the leak, but focused their ire on the draft’s conclusion that Roe must be overturned.

Such a move “would be an abomination, one of the worst, most damaging decisions in modern history,” said Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York in a speech on the Senate floor.

Meanwhile, the leaker’s motive remained unknown. It is possible that they were a Democrat who wanted to alert the nation to an upcoming judicial earthquake. But it is also possible they were a conservative who wanted to make it harder for any of the justices in the majority to change their minds, lest they be known as the right-leaning judge who saved Roe.

It’s possible that the leak will create an internal level of distrust in the court that might not have previously existed, says Kimberly Mutcherson, a professor of law at Rutgers in Newark, New Jersey.

“If nothing else, what it suggests to us is that the idea of the court as a sacred body and a sacred institution has been shaken,” says Professor Mutcherson.

Guttmacher Institute

The case at issue in the draft decision, Dobbs v. Jackson, stems from a challenge to a Mississippi law that limits abortion rights at 15 weeks.

“We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled”

Written by Justice Samuel Alito, the draft decision gives no indication of which other justices are inclined to join the opinion, as is customary for drafts. Politico reported that in the conference held after the court heard oral argument, Justices Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett all voted with Justice Alito. As of this week, that alignment had not changed, according to Politico.

The 98-page draft represents a full-throated skewering of the court’s five decades of abortion jurisprudence, most notably 1973’s Roe, which established a constitutional right to abortion, and 1992’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which upheld Roe’s central holding.

“We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled,” writes Justice Alito in the draft, which makes no exceptions for rape or incest. “The Constitution makes no reference to abortion, and no such right is implicitly protected by any constitutional provision.”

Such a reversal of current law would bypass stare decisis – a doctrine holding that the court should follow a historical precedent when ruling on cases with similar scenarios and facts. It would also be the first time in modern history that the court has overturned an individual right.

Pushing back against the argument that the right to abortion is “deeply rooted” in the country’s history and tradition, Justice Alito describes the claim that abortion wasn’t a crime under common law as “plainly incorrect.” The opinion’s appendix lists some U.S. state laws criminalizing abortion dating back to 1825.

The draft opinion also challenges the foundational constitutional basis for the right to abortion: the due process clause of the 14th Amendment. (No state shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”)

For decades the Supreme Court has read the due process clause to protect a variety of rights that are “unenumerated” – unmentioned in the Constitution’s text – but still “substantive.”

Abortion has been one such unenumerated right. Others based on the same legal foundation include same-sex and interracial marriage, and the right to contraception.

Justice Alito holds that the federal right to abortion can be struck down without endangering same-sex marriage and other private rights.

Abortion is “sharply distinguish[ed]” from other substantive due process rulings, he writes, because, essentially, the life of an unborn child is at stake.

“Nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion,” he adds.

But the opinion is far from definitive on that important question.

“It’s really hard to believe that that is true when you actually read the way the opinion is couched. He writes things like, well, the word abortion doesn’t appear in the Constitution. Well, neither does the word woman,” says Professor Mutcherson. “I mean, there are lots of things that don’t appear in the Constitution, right?”

And Justice Alito cannot predict how future justices would interpret his decision.

“That suggests to many experts that they may go farther than this. It’s really hard to know. But I think same-sex marriage bans are probably back on the table as well,” says Professor Segall.

Justice Alito concludes in the draft opinion that it isn’t the court’s concern to “know how our political system or society will respond to today’s decision.”

“Even if we could foresee what will happen, we would have no authority to let that knowledge influence our decision,” he adds.

What one activist wants to see

One anti-abortion activist thinks the main problem in the abortion space right now isn’t legal, but something else.

“We have a culture problem, a heart problem, and it is multifaceted,” says Cherilyn Holloway, founder of Pro-Black Pro-Life, a progressive anti-abortion organization in Ohio.

Following oral argument in the Dobbs case, Ms. Holloway and her friends knew overturning Roe was becoming likely. But they decided they had not done enough to prepare for that moment.

“It’s really time to take our eyes off of the Supreme Court and put our eyes on our communities, to these families and these women and the unborn, and figure out what needs to happen so that this decision doesn’t seem catastrophic,” Ms. Holloway says.

People legislating on behalf of unborn children at all political levels have been inconsistent when it comes to issues that can ease the burdens that come with giving birth, such as parental leave, health care for women and children, and food assistance programs, she adds.

The reproductive-rights side argues that poor Black women need access to abortion, says Ms. Holloway.

“No, what poor Black women evidently need are better-paying jobs, better opportunities, better and more resources,” she says.

Uncharted territory

However, at the moment Washington is intently focused on how the U.S. political system and society would respond to the demise of Roe – if that is what the final opinion, released sometime in the next two months, indeed does.

It’s possible it could motivate Democratic turnout, softening expected midterm losses in the House. But it’s also possible that abortion is not a top-tier issue for voters, as inflation and other economic markers are.

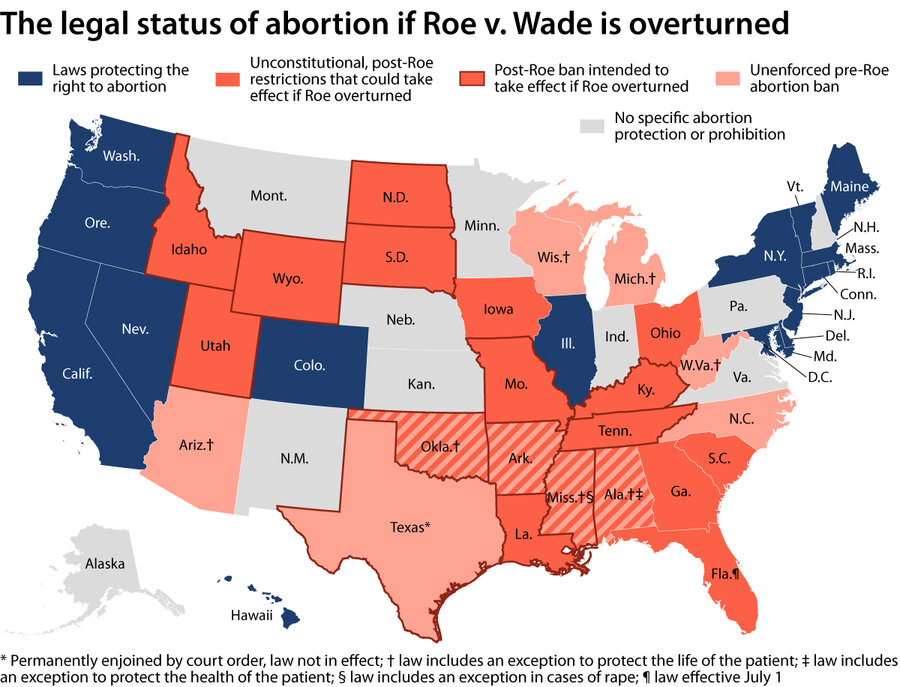

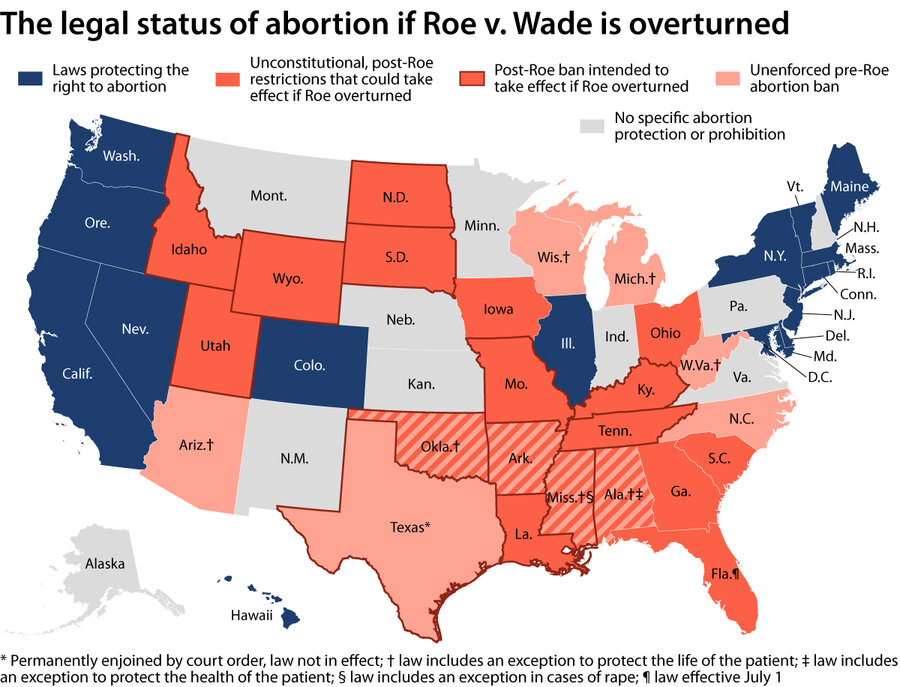

What it is likely to do is raise the importance of abortion as an issue in state politics, say some experts. That’s because if Roe is overturned, it is states that will be setting the terms for abortion in their borders.

If abortion rights are overturned, the effect might be most acutely felt in gubernatorial races in the battleground states of Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, tweeted Amy Walter, publisher of the Cook Political Report, on Tuesday.

“Uncharted territory politically,” Ms. Walter tweeted.

It’s also uncharted territory legally. Twenty-six states are likely to ban abortion if Roe is overturned, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a research and policy organization that supports abortion access. Meanwhile, liberal states like California, Washington, and Maryland are planning to expand abortion access in anticipation of the Supreme Court abortion decision.

And that barely scrapes the surface of the potential complexity that could arise without a federal right to abortion. Missouri lawmakers, for example, are considering a bill that would empower private citizens to sue anyone who helps a Missouri resident get an abortion in another state. California and Connecticut have responded with bills that would shield abortion providers and patients from lawsuits initiated by other states.

The landscape is very different from that in the 1970s.

“We’re not going back to the pre-Roe world,” says Mary Ziegler, a professor at Florida State University College of Law, who was interviewed before the leak. “We’re going to a world where abortion medication is available on the internet.”

And that would raise another host of constitutional questions, says Rachel Rebouché, interim dean of Temple University Beasley School of Law. “The endgame for states like Missouri is not just to ban abortion but to ban it everywhere,” she adds. “But if you’re trying to stop people from [accessing] medication abortions, there will have to be some kind of focus on the patient ordering it and receiving it.”

If that comes to pass, it would mark a significant shift in abortion policy.

To date, even states calling for restrictions on abortion have avoided targeting the women seeking abortions. Instead, providers and, more recently, citizens who “aid and abet” women have been the targets. But that may change, says Professor Ziegler.

If you punish doctors and others, “maybe you get some enforcement of the law, but there will be lots of cases where you can’t,” she adds. “Then you’re left with a stark choice.”

“For so long the only conversation was, how does the movement get rid of Roe?” she continues. “There was much less of a conversation around once Roe is gone, what does the movement actually want, and how does the movement actually ban abortion?”

Guttmacher Institute

On Russia, is US policy edging from defense to offense?

The Biden administration now seems to see an opportunity to weaken Russia – a shift that reflects lessons learned so far from the war in Ukraine. But concerns about escalation remain.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

On a surprise visit to Kyiv last week, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin said the United States wants “Russia weakened to the degree it cannot do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine.” Three days later, President Joe Biden asked Congress for another $33 billion in aid to Ukraine – two-thirds of which would go to security.

Before February, the administration had resisted this kind of aid, in part because it didn’t want to provoke the Kremlin. But it’s now sending Kyiv combat drones, howitzers, stinger missiles, and javelins. How did a White House so concerned with escalation just two months ago pivot to saying it wants to weaken a nuclear rival?

Part of the answer stems from the conflict itself. Russia’s military has not lived up to expectations, and Ukrainian defense has shown high returns on investment. At the same time, the U.S. seems to be taking Russia’s ambitions in the region more seriously.

“We have an opportunity to end this threat for a generation, if not forever,” says Richard Hooker, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. “If we don’t, we’re going to find ourselves watching the same movie all over again in a few years.”

On Russia, is US policy edging from defense to offense?

The Biden administration’s goals for the war in Ukraine appear to be expanding beyond Ukraine.

On a surprise visit to Kyiv last week, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin said the United States wants “Russia weakened to the degree it cannot do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine.”

Even for an administration whose objectives in the conflict haven’t always been entirely clear, the comment was notable. White House officials have so far focused on defending Ukraine from an aggressive neighbor. Now the U.S. seems to be saying it sees an opportunity to ensure that neighbor can’t become aggressive again.

Three days after Secretary Austin’s comment, President Joe Biden asked Congress for another $33 billion in aid to Ukraine – more than twice the $13.6 billion approved in March, and two-thirds of which would go to security. The request would transfer heavy weaponry, including missile defense systems and armored vehicles, and is meant to fund Ukraine’s defense for the next five months.

Before February, the administration had resisted this kind of military aid, in part because it didn’t want to provoke the Kremlin. But it’s now spending billions sending Kyiv combat drones, howitzers, stinger missiles, and javelins. How did a White House so concerned with escalation just two months ago pivot to saying it wants to weaken a nuclear rival?

Part of the answer stems from the conflict itself. Russia’s military has not lived up to expectations, and Ukrainian defense has shown high returns on investment. At the same time, the U.S. seems to be taking Russia’s ambitions in the region more seriously.

“This is a significant new pillar of U.S. strategy,” says Lauren Speranza, director of the Transatlantic Defense and Security program at the Center for European Policy Analysis.

“We have realized that we cannot just contain Russia,” she says.

The question for President Biden and his Cabinet is how to harden its response without inciting a wider conflict. But Russia’s leaders are already responding with threats to do just that.

Last week, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said the U.S. was waging a proxy war that could risk nuclear retaliation. Russian President Vladimir Putin warned Western support for Ukraine would draw “lightning fast” consequences.

Those threats may be an indicator of Russia’s battlefield issues. Estimates of Russian casualties range from 15,000 to 22,000, with wounded soldiers likely numbering twice that. After an initial blitz into Ukraine’s east, Russia’s offense is now “plodding,” the Pentagon says.

The Kremlin’s rhetoric is actually a sign that U.S. aid is working and more should follow, says Richard Hooker, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

“At the outset the administration was very concerned about the appearance of direct intervention and was reluctant to provide long-range weapons like aircraft, like long-range artillery,” he says. “In the last week or so, we’ve seen what appears to be a policy shift.”

In just weeks, the Air Force has assembled new types of battlefield drones and trained Ukrainians to use them. After hesitating initially, Washington is sharing live battlefield intelligence with Kyiv. In Germany and two other undisclosed sites, the Florida National Guard is teaching Ukrainians to operate American howitzers.

The administration’s aid request and a lend-lease bill passed by Congress last week are visible commitments to continue that assistance over the long term.

Ukraine likely needs air power to retake territory, and the aid so far doesn’t quite meet the need, says Dr. Hooker. But it’s much closer to the need than the past two administrations reached, after the annexation of Crimea and the start of fighting in the Donbas, he says, and “given that we’re barely two months into this, it’s been a lot.”

Bradley Bowman, senior director of the Center on Military and Political Power at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, remembers working in the Senate in 2014 when then-Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko visited Congress. Following the annexation of Crimea, Mr. Poroshenko thanked the U.S. for its humanitarian aid but noted, wryly, that “one cannot win the war with blankets.”

Eight years later, America isn’t just sending blankets. The pace of aid has been “extraordinary,” says Mr. Bowman, with arms reaching Ukrainians just days after being approved in Washington.

Tens of thousands of Russian soldiers are still in Ukraine, fighting a deadly war of attrition and razing entire cities. And Mr. Putin may escalate regardless of what happens, given the stakes for his hold on power.

“They’re still there,” says Morgan Viña, a fellow at George Mason University’s National Security Institute. “That’s important to note – that Russia is still persisting with this war.”

Recent explosions in Transnistria, a disputed region of Moldova, may also indicate that the war is starting to widen. Mr. Putin has refocused his efforts on eastern Ukraine, but that doesn’t mean he won’t expand it later, says Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations.

Harsh economic and military costs mean Russia will already exit this war weaker, he says. “I don’t believe that explicitly calling for weakening Russia as a goal is a wise idea,” says Dr. Haass, who was director of policy planning for the Department of State from 2001 to 2003. “It reinforces Putin’s message that this is really not about Ukraine.”

Ms. Viña also would prefer U.S. policy to focus on a free Ukraine, with Russian weakness as a byproduct. Secretary Austin’s newly formed Ukraine Contact Group is a good example of how to achieve that, she says. The body of 40 U.S. allies has pledged to meet each month and coordinate aid to Ukraine. Germany, one of its members, has already pledged up to 50 armored vehicles.

Getting the balance right is difficult, though. Ukraine has a tight window to protect itself against a much larger adversary, and Russia is sure to perceive all foreign aid as provocative. Dr. Hooker, who served in the National Security Council under multiple administrations, knows how difficult weighing those goals can be. Russia’s threats need to be taken seriously, he says, but if it isn’t stopped in Ukraine, when will it be?

“We have an opportunity to end this threat for a generation, if not forever,” says Dr. Hooker. “If we don’t, we’re going to find ourselves watching the same movie all over again in a few years.”

A deeper look

Refugees from Ukraine escape the danger, but not the war

For more than 3 million Ukrainian refugees living in Poland, life is about resilience as they focus on maintaining income and education in a new country while monitoring news of the war back home.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

More than 3 million Ukrainians have sought refuge in Poland from Russia’s full-scale invasion, and now find themselves in limbo. Uncertain of how long they will stay in Poland and when it will be safe to return home, they find themselves faced with questions and choices over finding long-term housing, jobs, and schools for their children.

For Ukrainians and Poles, emotions are right beneath the surface. Hanna Hromova, a psychologist who herself fled Kyiv, is now in Warsaw working with patients online, through a psychological hotline, and at refugee centers.

Ukrainians who fled are dealing with feelings of guilt and sorrow as well as divided families with husbands and older relatives staying behind, while those in Ukraine are struggling with safety concerns and survival, enormous stress, and death, Ms. Hromova says.

“The people who are here, most of them will stay here for the foreseeable future,” says Katia Roman-Trzaska, whose foundation is aiding refugees. “Both Poles and Ukrainians need a lot of assistance. Tools to rebuild their life, either to stay or to go back home.”

Refugees from Ukraine escape the danger, but not the war

Iryna Lvovych takes out her phone and pulls up photos of her young, smiling family and of a garden where she grew tomatoes and berries in and around Irpin, Ukraine, which she called home for the past 10 years. Then she shows a photo of what remains of her family’s apartment building today.

“We will not return to Irpin. It’s dangerous,” says the mother of two. “Our apartment that we bought, the roof burnt off and it’s not livable.”

Ms. Lvovych is one of more than 3 million Ukrainians who have sought refuge in Poland from Russia’s full-scale invasion, and now find themselves in limbo. Uncertain how long they will stay in Poland and when it will be safe to return home, they find themselves faced with questions and choices over finding long-term housing, jobs, and schools for their children.

“The people who are here, most of them will stay here for the foreseeable future,” says Katia Roman-Trzaska, the founder of SOK Foundation, a nonprofit focused on helping foster care and underprivileged children. “Both Poles and Ukrainians need a lot of assistance. Tools to rebuild their life, either to stay or to go back home.”

“No one believed this would be a big war”

Russia’s war against Ukraine has created the largest refugee crisis seen in Europe since World War II. Over 5 million Ukrainians have fled, and Poland has taken in the highest number at over 3 million people, according to United Nations figures. Those Ukrainians join over 1 million who were already living and working in Poland prior to Feb. 24, when the war began.

This refugee situation has unique characteristics. It’s primarily women and children fleeing, since men 18 to 60 years old are not permitted to leave Ukraine. And Poles are taking Ukrainians into their own homes, not setting up camps like in other recent global crises.

Also, while Poland has been criticized for its response to refugees fleeing the Middle East and Africa, it has been widely sympathetic to Ukrainians fleeing the war on its border, a response partially rooted in a shared Soviet history with Ukraine and cultural similarities.

Polish cities, which are decked out in blue and yellow Ukrainian flags in a sign of solidarity, have seen their populations swell. Warsaw’s population has grown by over 17% and Krakow’s by 20%. Ukrainian is now commonly heard spoken on streets.

But few expected this, says Ms. Lvovych. “So many families thought this would be over in one, two, three days and they would return back,” she says. “And so many didn’t leave because of that. No one believed this would be a big war with a lot of losses.”

On the morning the war started, her family’s car was in a repair shop in Kyiv and her son’s passport was in an office being renewed – that building would later be bombed. Her husband, Yaroslav, managed to retrieve both their car and the passport while she started preparing to leave the next morning. That evening, they spent part of the night in the basement and could hear military activity in nearby Hostomel.

The next morning, Ms. Lvovych along with six other people piled into a Volkswagen Jetta, knowing they were heading for Poland with the goal of making it to Warsaw. After an arduous journey, Ms. Lvovych crossed into Poland on Feb. 28 with her 7-year-old and 1-year-old sons, Sviatoslav and Myroslav. Her husband stayed behind in the western Ukrainian city of Lutsk, where he is volunteering and continuing to work a remote IT job that now supports an extended family.

Ms. Lvovych, who works as an architect and interior designer, spent three weeks looking for an apartment in Warsaw and received help from a Polish family at the school where her sons are now students. The Polish family decided to help Ms. Lvovych in memory of their recently deceased grandmother, who was sent to Siberia as a child by the Soviets. “The Poles remember what the Soviets did to them,” Ms. Lvovych says.

Ms. Lvovych, who understands Polish but does not yet speak it, is grateful for all the help Poland has offered and says she feels bad about the stress so many Poles are living under, themselves wondering if their country could be attacked by Russia.

For now, Ms. Lvovych and her sons are trying to socialize with Poles in Warsaw. She has the apartment rent-free until the end of spring. She’s planning to return to Ukraine in late May on her son’s birthday and join her husband. “We’ll return and see what to do next,” she says.

History and trauma

Relations between Poland and Ukraine haven’t always been as strong as they are in the current moment. Painful historical events of the 1940s – including the Volhynia massacre of Poles, committed by Ukrainian nationalist groups, and Operation Vistula, the forced resettlement of Ukrainians under the Soviet-backed Polish communists – remain charged topics.

But right now, as the war enters its third month, Poles are continuing to help Ukrainians while also steeling themselves for what could be a much longer haul.

“Pretty much the whole country has pivoted to helping Ukrainians,” says Ms. Roman-Trzaska of SOK Foundation, who also founded Little Chef, a cooking school for kids. “Very quickly we realized that this is not a sprint. This is a marathon.”

Ms. Roman-Trzaska pivoted her foundation’s work and started making sandwiches for Ukrainians arriving at Warsaw’s Ukrainian House and building welcome packs containing basic hygiene products. Her group is now working with Ukrainian orphans in Poland running programs involving sports, singing, painting, and cooking. She is working on plans for Polish-language immersion classes for Ukrainian children this summer.

“We want to help them with integrating into Polish society and Polish schools, and we want them to learn the language,” she said. “Not to assimilate, which is the loss of your own culture, but to blend culturally. And this needs to happen for both sides.”

But she fears the war has entered a “precarious” period with online fake news and trolling having the potential to divide Poles. “This will take decades to heal,” she says. “We need the world to help us here.”

For Ukrainians and Poles, emotions are right beneath the surface. Hanna Hromova, a psychologist who fled Kyiv, is now in Warsaw working with patients online, through a psychological hotline, and at refugee centers.

Ukrainians who fled are dealing with feelings of guilt and sorrow as well as divided families with husbands and older relatives staying behind, while those in Ukraine are struggling with safety concerns and survival, enormous stress, and death, Ms. Hromova says.

“There is an intense desire for people to return [home],” she says. And Polish volunteers are also dealing with trauma, she adds.

In the countryside

Poles are encouraging Ukrainians to head for smaller cities. A large poster in Warsaw’s central train station in English and Ukrainian declares, “Big cities in Poland are already overcrowded. Don’t be afraid to go to smaller towns: they are peaceful, have good infrastructure, and are well-adapted.”

Svitlana Shevchenko took that advice, after she fled Zaporizhzhia with her teenage daughter Yliia, and Ms. Shevchenko’s friend Valentyna Kozlova and her 6-year-old son Maksim.

“The war started for me not from the moment they started to bomb us, but when I understood that” – she starts crying and Yliia finishes her sentence – “we had to leave.”

Their long journey involved waiting in the cold and taking bruising rides on packed trains. “This whole journey, it felt like it wasn’t happening to us. It felt like a retrospective of films about World War II. You don’t believe that this is happening in your lifetime,” Ms. Shevchenko says.

They crossed into Poland on March 6. At a refugee center, a Polish volunteer who spoke Ukrainian told them a priest in a small village near Rzeszów in southeastern Poland had offered to host four people in a building close to the church. They accepted.

“We are immeasurably thankful to the Polish people. We are pleasantly shocked by these people. I never even thought that people could feel another’s pain like this,” Ms. Shevchenko says. “War is terrible, but it has shown in the world that there are extraordinary, good, sincere people.”

Slowly the women and their children are settling into life. Yliia and Maksim are attending Polish school, and Yliia is also continuing Ukrainian school online. Not too long after they arrived, another friend of theirs with her daughter also came to the village – giving the women a small Ukrainian community.

But Ms. Shevchenko, who worked as a journalist in Ukraine, admits to feeling lost and experiencing some depression. “We arrived in a foreign country without a home, job, a perspective; we don’t have a future,” she says. “In February the war began, time goes on, the seasons are changing, but we are stuck in February, all of us. Time isn’t moving forward.”

She is focusing on learning Polish, which will open up job opportunities, and hopes to be able to communicate what she’s feeling and thinking to Poles soon. While in recent weeks some Ukrainians have started to return home, the women think it’s still too dangerous in their city. For now, they are thankful to be safe and constantly monitor their phones for news from home.

“We all have one wish,” Ms. Shevchenko says. “We don’t even say it out loud to each other – we want the war to end. There are a million questions; we all understand that tough times are ahead. We don’t know if the war will end, how long it will last. We don’t know if our cities will survive or if occupied territories will again be freed. But we understand that even if it’s like that, we will need to renew and rebuild our country, and it will be tough.”

Emily Johnson contributed reporting.

Sowing justice: When farming is about more than food

Charity can be a vital tool to fill immediate need. But when it comes to food security, generosity alone doesn’t address root problems. In Toronto, a nascent effort shows how nourishing empowerment can be.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Aliyah Fraser has always been fascinated by the powerful simplicity of growing food.

But it took a long time – a pandemic and a social justice movement – to consider farming a viable career option. “I never saw farmers that looked like me,” she says.

Now, she’s part of a growing movement to diversify food production in Canada. Amid scarcity brought by pandemic disruptions and soaring inflation, that work is helping to shift the conversation about food insecurity from one that hinges on charity to alleviate hunger to a longer-term goal of Black empowerment and food sovereignty.

In April, the Toronto City Council voted to update its food charter to address inequalities in the system. The move is part of a broader effort to support Black-led food security initiatives.

“To get where we want to go to address the inequities that we experience and that hold us back or keep us down,” says Winston Husbands, a food justice activist, “we need to be in a position to exercise some kind of stewardship of the food system for our own needs and in our own interests.”

Sowing justice: When farming is about more than food

Aliyah Fraser has always been fascinated by the powerful simplicity of growing food. It started in her grandmother’s garden in Toronto where she’d watch in awe as tomatoes, pumpkin, and squash would swell. “I’d just run around like a little rascal, eating all the ripe raspberries,” she says. “That garden has always been my safe space.”

But it took a long time – a pandemic and a social justice movement – to consider farming as a viable career. “I just never really saw myself as a farmer. I never saw farmers that looked like me,” she says, plunging a homemade, wooden dibbler into the earth, planting garlic on a chilly afternoon in rural Ontario.

It’s about as mundane a task as any farmer does. But the larger objective, as she begins her second season as the owner of Lucky Bug Farm, is far less prosaic. “What I’m trying to model with Lucky Bug Farm, as a socially just, environmentally sustainable, and financially solvent farm that is run by a Black woman shouldn’t be so radical, revolutionary, or never seen before. But it is.”

She joins other farmers, agricultural groups, and justice advocates pushing to diversify food production in Canada – and enable underserved communities to have more control over the system. Amid scarcity brought by pandemic disruptions and soaring inflation, that work is helping to shift the conversation about food insecurity from one that hinges on charity to alleviate hunger to a longer-term goal of Black empowerment and food sovereignty. It’s part of a growing movement across North America.

“The normal way of measuring food insecurity is to ask people about how often ... they must go hungry,” says Winston Husbands, a food justice activist at Afri-Can FoodBasket in Toronto. “Those are good indicators, and some of the instruments that people use to address food insecurity work in the short term. But they do not generate food sovereignty.”

“To get where we want to go to address the inequities that we experience and that hold us back or keep us down,” he adds, “we need to be in a position to exercise some kind of stewardship of the food system for our own needs and in our own interests.”

Changing the narrative

In Toronto, Black families are 3.5 times more likely to face food insecurity than white families, according to city figures, with 36.6% of the city’s Black children living in food-insecure homes.

Paul Taylor, executive director of FoodShare Toronto, a nonprofit leader in community food justice, says that to address the disparities, the narrative needs to be challenged and the structural racism at play understood. “Black folks aren’t inherently more vulnerable to food security,” he says. “Our response as a country has been to collect other people’s leftovers or corporate waste to redistribute without ever saying, ‘Why are these corporations that are producing waste not paying living wages?’”

FoodShare Toronto, which also helped launch Flemo Farm in 2021 to bring underrepresented community members into urban agriculture, led a petition in Toronto for a new food charter to address inequalities in the system – which the City Council adopted in April. The city also approved a five-year Toronto Black Food Sovereignty Plan in October to support Black-led food security initiatives, including more access to green space for urban farming, markets, and distribution.

Afri-Can FoodBasket, which helped push through the citywide initiative, has been advocating for food justice since the ’90s, says Dr. Husbands, an associate professor at University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health. But scarcities in the wake of the pandemic, which disproportionately impacted Black and Indigenous communities, and a societal awakening after the murder of George Floyd have helped catalyze the issue.

Broadening the face of farming

Groups like the Ecological Farmers Association of Ontario have shifted their own thinking about the role they play in the fight for equality. Last year they hired Angel Beyde as their equity and organizational change manager – an effort to put an anti-racism lens on all of their work and help lower the barriers for underrepresented farmers, including access to land and capital, education and mentorship, and representation, says Ms. Beyde.

It’s not that the farmers association didn’t stand behind those values before, says Ali English, the group’s executive director. “But we used to think this social justice work was the work of other organizations,” she says. “And it’s become very clear to so many of us that doing equity and anti-racism work is something we all have to be doing actively, and that if we’re not, we’re very much complicit.”

Many of the obstacles for Black farmers trace back to historic government action and policy, and many Canadians remain unaware of their country’s history of slavery and racism, says Ms. Beyde. “There were once thriving Black communities that owned their own land and farms, and then a series of systematic, racist actions, many of which came down from the government, disenfranchised those folks and removed them from their land,” she says.

Today, stigmas and perceptions remain throughout agriculture. Many simply hear the word farmer and picture a white man, says Ms. Fraser, who previously worked as an urban developer but became disillusioned by the lack of social and environmental justice in that work. She also says Black farmers face stigmas in their own communities, which she says span back hundreds of years to traumas of slavery. “When I told my family, ‘I want to be a farmer,’ they were like, ‘You had a good office job. Why would you want to give that up to do hard field work?’”

But she had come across a program called Growing in the Margins, a nonprofit that mentors Black and Indigenous youths to become farmers in the Toronto area. It gave her the confidence to set out on her first season – growing curly kale, cherry tomatoes, and collard greens. For her second season, she is renting a quarter-acre farm in Baden, Ontario, and sells her produce at a weekly farmers market in Kitchener. It’s a steep learning curve, but she feels she is playing a small part in changing the paradigm.

“I think local agriculture is important, I think urban agriculture is important, I think sustainable ecological agriculture is important, but something that I find often gets missed is making sure that the food system represents the people who live in this province,” she says, “and understanding it’s not working for everyone, and it marginalizes a large number of people.”

In Pictures

Bucking Azorean traditions, these women take to sea

Despite gender stereotypes and hurdles facing the industry as a whole, a group of women have overcome barriers to fish commercially in the Azores.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Eduardo Leal Contributor

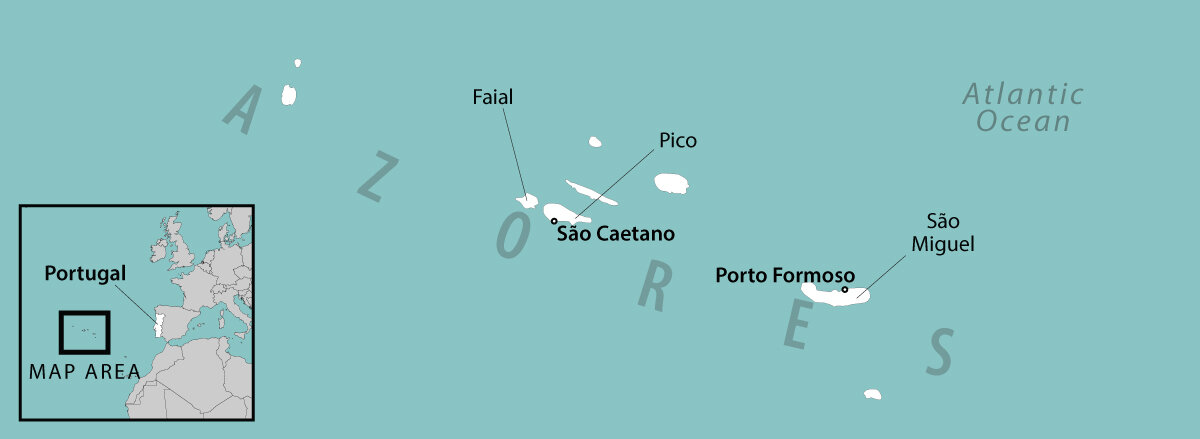

Traditionally, the role of women in the Portuguese Azores’ fishing industry was confined to the shore: preparing troughs, bait, and nets, or cleaning and selling the day’s catch.

Women were historically excluded from going out on boats because they were considered not strong enough to do the work. Economic shifts – whether through dwindling fish stocks or competition from bigger boats – changed that slightly.

In 2008, of the 153 women who worked in extractive fishing, 12 worked at sea, according to Umar-Açores, a women’s rights group. Today there are only four, perhaps the last of a dwindling breed of iconoclasts as the fishing industry as a whole continues to take a hit.

Lídia Silva and her sister, Sara, helped their father on the family’s boat when their mother stopped going to sea. The low pay drove Sara to seek employment elsewhere, but Lídia has obtained a fishing license and says she hopes to take over from her father when he retires.

She can’t see herself anywhere else.

Bucking Azorean traditions, these women take to sea

The traditional role of women in the Azores fishing industry was usually limited to the support they provided on land, whether in the preparation of troughs, bait, and nets or in the logistical work of cleaning and selling fish. But a small number of women, mostly in fishing families, have managed to go to sea, and they’ve found that the grueling work suits them.

In 2008, of the 153 women who worked in extractive fishing, only 12 worked at sea, according to Umar-Açores, a women’s rights group. Today there are only four, possibly the last Azorean fisherwomen. Women have historically been excluded from going out on boats because they were considered not strong enough to do the work, and because they were thought to be a distraction to male crews.

But as small fishing operations have struggled with higher costs, dwindling fish stocks, and steeper competition from larger boats, some fishing families have seen wives or daughters step up out of economic necessity.

Some of these women, like Lídia Silva, have found they liked the freedom of being out on the water, and they feel a sense of accomplishment in showing what women are capable of. Ms. Silva and her sister, Sara, helped their father on the family’s boat when their mother stopped going to sea. The low pay drove Sara to seek employment elsewhere, but Lídia has obtained a fishing license and says she hopes to take over from her father when he retires.

Even with all the difficulties inherent to the profession, Ms. Silva can’t see herself anywhere but on the sea.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

War crimes justice through the eyes of survivors

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Since it was set up two decades ago, the International Criminal Court has followed its founding aim of not allowing genocide or war crimes to “go unpunished.” Yet in a report to the United Nations last week, the court’s chief prosecutor posed a potentially radical shift in holding perpetrators of such crimes accountable. With Russia’s military killing civilians in Ukraine, his ideas may deserve global notice.

“Our new approach prioritizes the voices of survivors,” Karim Khan told the Security Council on April 28 in remarks on the ICC’s work in Libya. “To do so we must move closer to them. We cannot conduct investigations, we cannot build trust, while working at arms-length from those affected.”

The new approach outlined by Mr. Khan for Libya reflects a view that moving conflict-torn societies beyond mass violence requires more than the punishment of selected individuals.

As the world watches another humanitarian crisis in Ukraine, a new ICC emphasis on listening to survivors of atrocities may offer a new model of international justice.

War crimes justice through the eyes of survivors

Since it was set up two decades ago, the International Criminal Court has followed its founding aim of not allowing genocide or war crimes to “go unpunished.” Yet in a report to the United Nations last week, the court’s chief prosecutor posed a potentially radical shift in holding perpetrators of such crimes accountable. With Russia’s military killing civilians in Ukraine, his ideas may deserve global notice.

“Our new approach prioritizes the voices of survivors,” Karim Khan told the Security Council on April 28 in remarks on the ICC’s work in Libya. “To do so we must move closer to them. We cannot conduct investigations, we cannot build trust, while working at arm’s-length from those affected.”

The primary motive for creating the ICC was to prevent mass atrocities like the genocide in Rwanda or ethnic cleaning in Bosnia-Herzegovina from happening again. But its work is notoriously slow and – because it is based in The Hague, Netherlands – far removed from the affected populations. In 20 years it has brought just 31 cases to trial.

The new approach outlined by Mr. Khan for Libya reflects a view that moving conflict-torn societies beyond mass violence requires more than the punishment of selected individuals. It has four parts: a greater emphasis on investigating sexual and gender-based crimes as well as the financing of a conflict; involvement of witnesses and survivors in investigations; building judicial capacity and accountability in governments; and strengthening accountability and cooperation among regional blocs of nations and meddling foreign powers.

Those measures reflect Mr. Khan’s emphasis on the ICC’s “principle of complementarity,” which states that a case cannot be brought before the international tribunal if it is already under investigation by an individual state. That rule, the prosecutor told the Security Council last November, binds humanity to universal values. It is an acknowledgment, he argued, that nations have the primary responsibility of enhancing stability and fostering reconciliation.

Colombia’s 2016 peace agreement that ended a long civil war illustrates that point. The pact was successful in large part because the war’s survivors were involved in the negotiations. “The victims have taught me that the capacity to forgive can overcome hatred and rancor,” said Juan Manuel Santos, who was the country’s president at the time. The pact led to the creation of a special judicial panel that favored restorative projects over retributive sentences for perpetrators who gave full and truthful accounts of their crimes.

Critics have lamented the slow pace of the panel’s work. But as a model of reconciliation it has demonstrated the advantages of homegrown justice. As a result, Mr. Khan announced last October that the ICC would close its preliminary investigations of war crimes committed during the conflict that lasted 52 years.

In 2011, the ICC took up alleged war crimes in Libya committed under the regime of former dictator Col. Muammar Qaddafi. The court has since expanded its remit to cover atrocities committed during a subsequent civil war that displaced hundreds of thousands. Mr. Khan’s report to the Security Council was an acknowledgment of the ICC’s slow place – only three Libyan cases have been tried. But it was also a carrot. Since October 2020, a fragile cease-fire has held. Mr. Khan’s new approach is an attempt to promote reconciliation and cooperation between the two sides.

“This situation cannot be a never-ending story,” Mr. Khan said. “Justice delayed may not always be justice denied, but justice that can still be arrived at.”

As the world watches another humanitarian crisis in Ukraine, a new ICC emphasis on listening to survivors of atrocities may offer a new model of international justice.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Peace – to every heart

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By William E. Moody

Opening our hearts to God’s perfect peace is a powerful starting point for nurturing healing and harmony in our homes, communities, and beyond.

Peace – to every heart

Today, a deep yearning for peace touches human hearts everywhere. Thousands of years ago, the writers of the Bible also felt this need and included many inspiring references to God bringing peace to people’s lives. In the book of Psalms, for example, we read, “The Lord will give strength unto his people; the Lord will bless his people with peace” (29:11). And later, in the New Testament, we find this salutation near the end of the Epistle to the Ephesians: “Peace be to the brethren, and love with faith, from God the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ” (6:23).

Throughout the Old Testament, the Hebrew word used for peace is predominantly “šālôm,” commonly rendered “shalom” in English. This peace not only refers to the absence of conflict between individuals or nations but also points to an inner quietness for each of us, a spiritual tranquility that includes a genuine sense of completeness or wholeness.

The healing works of Jesus could be considered ultimate acts of shalom – of bringing a new recognition of an individual’s completeness and a spiritual tranquility to those he healed. Think, for instance, of a man with leprosy who had been an outcast in his own community because of the widespread fear of his illness. Or of the woman who had been experiencing severe bleeding for 12 years and found no relief no matter how hard she had tried.

When they were healed by the spiritual power of the Christ – the divine idea of God bringing light and grace to human consciousness – these individuals certainly must have felt not only gratitude and joy and a stronger faith in God but a deep quietness of the heart.

And today, if we are confronting disturbed or fractured lives, or even societies, recognizing in our prayers that God has provided genuine spiritual wholeness for all of His children is a powerful force for healing and good. Each of us is, in truth, the spiritual reflection of God, divine Love. And just as this infinite Love is itself perfectly complete, God’s likeness – you and I – must also be complete. God’s reflection does not lack spiritual quietness or stability.

To realize and affirm in our prayers that God’s man is the forever complete and whole expression of God helps establish in our lives here and now that true peace, shalom, is God’s will for each of us and for all of us.

This peace is the law of God, a spiritual law that cannot be undermined, obstructed, or made of no effect. It can’t ever be displaced by people, events, or circumstances. No matter what the situation around us may be or how disrupted or destroyed things may appear, we can avail ourselves of the perfect peace and guidance of God (who has nothing to do with evil) and be tenderly led to each next step that tangibly establishes this peace in our hearts and lives.

There’s another passage in the New Testament that is both inspiring and practical in helping to pray about peace. In The Living Bible translation we read: “Don’t worry about anything; instead, pray about everything; tell God your needs, and don’t forget to thank him for his answers. If you do this, you will experience God’s peace, which is far more wonderful than the human mind can understand. His peace will keep your thoughts and your hearts quiet and at rest” (Philippians 4:6, 7).

Mary Baker Eddy, who founded Christian Science, also provides guidance on peace in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.” She writes, “Spiritual living and blessedness are the only evidences, by which we can recognize true existence and feel the unspeakable peace which comes from an all-absorbing spiritual love” (p. 264).

Our own inner peace, our genuine shalom, is intrinsically linked to God as infinite Love blessing each of us, to our own expression of God’s love from day to day and moment to moment, to “an all-absorbing spiritual love.” And when we think of the peace that society itself so needs today – this pure, divine peace of God – we are encouraged to know that our prayers not only help to keep our own thoughts and hearts quiet and at rest but can increasingly bring to light for our world “all the glories of earth and heaven and man” (Science and Health, p. 264).

The Living Bible, copyright © 1971. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved.

Adapted from an editorial published in the April 18, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

For a regularly updated collection of insights relating to the war in Ukraine from the Christian Science Perspective column, click here.

A message of love

A musical respite

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow. Scott Peterson will have a story from the Donbas region in Ukraine about lessons Ukrainian soldiers have learned so far about fighting the Russians.

If you’d like to learn more about what a post-Roe landscape might look like, we have several stories for you: Why America’s “rights era” is ending, why the Supreme Court decision won’t end the culture war, and why the U.S. is moving in the opposite direction on abortion from many other countries.