- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Ukraine’s wartime schools: Intensity, purpose, and an eye to safety

- Lessons in survival from a bone-dry land

- Union rebound? AFL-CIO’s Shuler sees promise, but long road ahead.

- Presidential plantation shifts telling of history to let all voices rise

- A voice that wouldn’t be ignored: Nellie Bly and the pursuit of truth

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What the Avengers can tell us about the economy

Economists don’t wear capes. But in an unconventional new book, Marian Tupy and Gale Pooley take on a villain familiar to fans of the Avengers movies: Thanos. The intergalactic warlord tried to kill half of all living beings because he feared that overpopulation would consume the universe’s finite resources.

In “Superabundance,” the political economists cite Thanos as an example of the still-influential Malthusian idea that population growth will outpace the world’s ability to feed everyone. As a counterargument, they examine the trend lines of “time prices,” the length of time that a person has to work to earn enough money to buy something. In 1850, a factory worker had to work 2 hours and 50 minutes to buy a pound of sugar. In 2021, the same amount of sugar costs just 35 seconds of work.

“Commodities, but also food and even some services – certainly finished goods – are becoming more abundant every 20 years,” says Mr. Tupy, a senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute. “Every 1% increase in population reduces time prices of goods and services by 1%. And that tells you that, on average, every human being produces more than they consume.”

The idea that resources are becoming less scarce with increasing population is counterintuitive. There are a finite number of atoms on Earth, says Mr. Tupy, but ideas are infinite. A population of 8 billion will produce more groundbreaking innovations than the 14 million people who inhabited the world as late as 3000 B.C. There’s one other major difference between modern and ancient times: the spread of human cooperation and the ability to share knowledge.

The two authors believe such innovation is the key to solving environmental problems, such as reducing trash. In the 1950s, for instance, it took 3 ounces of tin to produce a can of Coca-Cola. Now it’s half an ounce.

How would Mr. Tupy respond to critics who argue that the perpetual growth of material goods is a poor definition of prosperity?

“The more time we have to spend at work, the less time we have on other things,” says Mr. Tupy. “Having the extra time to do other things is, in our view, a good measure of prosperity.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Ukraine’s wartime schools: Intensity, purpose, and an eye to safety

“School safety” is a buzzword everywhere, more so in a country at war. Yet as Ukraine launches a new school year, the war has also sharpened a seriousness of purpose – among educators and students alike.

As an estimated 4 million Ukrainian children started a new school year Thursday, there was much that was new about this opening day of school with the country at war.

In-school learning can only take place in buildings with bomb shelters, or one immediately adjacent. More time will be dedicated to safety and to what school staff call “psychological first aid” – class discussions on dealing with the stresses war brings.

Teachers displaced from conflict zones will be enabled to continue working remotely with their same students, including those still living in occupied areas. The national course syllabus has been tweaked, as well: more Hemingway, less Dostoyevsky.

But perhaps most important of all, some of the country’s educators say, is a new sense of purpose for this school year.

“The message I’m getting from my students is that they really want to get back to school and get an education to use in the future,” says Marko, an English and geography teacher.

“Unfortunately we have had to add such things as ‘safety from mines’ to the topics of instruction,” says Andrii Vitrenko, Ukraine’s deputy minister of education. “But we are seeing that children want to study and learn, it is our task to make it possible to fulfill those dreams.”

Ukraine’s wartime schools: Intensity, purpose, and an eye to safety

As a rising first grader, Masha Komarova was anxious to start school and make new friends in her new home in Makariv, a village about an hour west of Kyiv.

There was just one problem: Masha and her family had arrived in April from Kherson in southeastern Ukraine, a city now occupied by Russian forces. And in Kherson, Masha spoke Russian and was preparing for first grade subjects that would be taught in Russian.

But in Makariv – a town that suffered heavy Russian shelling for a month at the start of the war and was partially occupied but never fell to the aggressors – school instruction is strictly in Ukrainian.

“We’ve been working on the Ukrainian all summer, and she’s got it to where she’ll be fine with it,” says her mother, Anastasiia Komarova. While her mother speaks, Masha jumps around the steps to her new school, Makariv Lyceum No. 2, the Ukrainian national symbol on her T-shirt and an orange sucker in one hand.

“It’s been a little tough; there are words she doesn’t understand,” Ms. Komarova adds, “but she has the child’s ability to learn fast.”

As an estimated 4 million Ukrainian children started a new school year Thursday, there was much that was new about this opening day of school with the country at war.

In-school learning can only take place in buildings with bomb shelters, or with an accessible bomb shelter immediately adjacent. More time will be dedicated to safety education and to what school staff call “psychological first aid” – class discussions on dealing with the stresses the war brings, and allowance made for individual consultations with beefed-up school psychologist staffs.

A few instructional hubs have been set up to allow teachers displaced from the hottest conflict zones in the east and south to continue working remotely with their same students, including those still living in occupied areas.

The national course syllabus has been tweaked, as well: more Ukrainian history in history classes; and, in world literature, out with the likes of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, in with Hemingway and Jack London.

“New motivation”

But perhaps most important of all, some of the country’s educators say, is a new sense of purpose for this school year.

“The message I’m getting from my students is that they really want to get back to school and get an education to use in the future,” says Marko, who asked that his last name not be used, a primary and secondary English and geography teacher in the Dnipropetrovsk oblast. The central Ukraine region is now home to thousands who have been displaced within the country.

The war has provided “a new motivation for students to study hard and find a profession where they can do something good to rehabilitate and renew the country,” he says. “They want to use all they’re learning in school to help people.”

In Kyiv Thursday morning, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy sounded a serious but similar note, addressing Ukraine’s schoolchildren on television from a sunny hilltop overlooking the city.

“This year’s Sept. 1 is very different from the 30 previous ones” in Ukraine’s history as an independent country, he said. The Russian invaders “stole part of your childhood, part of your youth,” the president said, “but you are free. You always will be. So be worthy of your freedom,” he added, “and of our Ukraine.”

At Ukraine’s Ministry of Education, officials say that while the war has brought many changes, the basics of the national endeavor to provide children with an education remain the same.

“Unfortunately we have had to add such things as ‘safety from mines’ to the topics of instruction,” says Andrii Vitrenko, Ukraine’s deputy minister of education. “But we are seeing that children want to study and learn; it is our task to make it possible to fulfill those dreams.”

The ministry says that less than a half-million of Ukraine’s prewar student population of 4.2 million have left the country, with some of those who have fled with their families to neighboring countries signed up to “attend” their Ukrainian schooling online.

Accommodations for all

Officials are confident that the three-tiered education system they developed for this year – some of Ukraine’s roughly 13,000 schools will be online only, some with only in-school instruction, and some a hybrid of the two – will accommodate all students from kindergarten to high school.

Clad in an olive-drab T-shirt he admits with a smile follows a “precedent” set by President Zelenskyy, Mr. Vitrenko says Russia’s invasion provided Ukrainians with another lesson about education.

“What we learned is that most of the Russian soldiers who came here with this war don’t even have a midlevel education,” he says. “That gives us even more reason to educate our children” to be better people.

In the capital, Kyiv, officials say the city has worked hard to make sure all children – both city residents and the thousands who have been displaced and have settled with their families here – are “in school” with either in-person or online classes.

But no priority has topped that of guaranteeing the security of children and school staffs this new school year with the country at war, Kyiv education officials say.

At a press conference this week in Kyiv’s first-through-11th-grade Millennium School, officials invited journalists to the school’s bomb shelter to underscore the city’s twin goals of accommodating as many students as possible in school buildings – what they call “offline” education – while keeping everyone safe.

“We’ve put all of our resources into assuring the safety of our children,” says Valentin Mondriivskyi, deputy head of the Kyiv city administration. Noting at the same time that the city expects nearly 80% of this year’s estimated 178,000 student population to opt for in-school learning, he adds, “This tells us how important the offline system is for a good education” in the eyes of parents, students, and teachers.

Highlighting the underground space’s art tables for younger children and discussion circles for older students, Mr. Mondriivskyi says, “We want to make these shelters not a territory of fear, but a place of learning and development.”

A place for those displaced

Given its resources and isolation from the front lines, the Kyiv school district is one of the more unscathed by the war. But even here, numbers reveal a shrunken system that at the same time must adapt to accommodating a new student population – those internally displaced.

The city’s anticipated student population of 178,000 is down sharply from last year’s 300,000. But included this year will be about 3,800 students displaced from the war’s hotter conflict zones – although officials say they expect that number to rise as the school year progresses.

Mirroring the student population decline, the city’s total number of teachers and school staff members is also down considerably, from 77,000 last year to 57,000 this year – declines that hint at the millions who have left the country seeking refuge from the war.

But in many other parts of the country, particularly in the east and closer to the front lines, the new school year is much more precarious.

Some regions, or oblasts, have decided to offer classes online only – for the safety of students and staff, but also because many school buildings are still being used as shelters for those internally displaced – a population the United Nations’ International Organization for Migration estimates at 6.9 million and still growing.

In a recent study, the International Organization for Migration found that at the beginning of July, nearly 1 million Ukrainians were living in 5,670 “collective sites” across the country, with schools, kindergartens, and student dormitories making up nearly three-quarters of those facilities.

And some schools are still being repaired after being damaged by Russian fire.

In Makariv, the town’s Lyceum No. 1 is being restored, brick by brick, from the artillery shelling it took in March.

“Of course the building can be rebuilt, but the children who were traumatized by having their school attacked in this way are going to need special attention,” says Natalya Kochkur, the school’s director.

Noting that two of the school’s students were killed in the shelling of Makariv, while two of the school’s graduates have died on the front lines, she says, “Our teachers are ready to educate our children and prepare their future.”

Of the fallen graduates, she adds, “We could say they died for this – for a peaceful and free Ukraine.”

Trade-offs

Yet not all of Makariv’s displaced families say they are finding the kind of “we’re in this together” spirit that officials talk about.

“I went to the school, but what I heard was a lot of bureaucracy and administrative things,” says Marie Zavrazhna, who arrived in Makariv with her two children this summer from the embattled region of Kharkiv. While daughter Varvara will follow her design courses online, son Ilya is entering the third grade in Makariv.

Yet even though Ms. Zavrazhna worries that overloaded school staff won’t have the time to receive Ilya “in a good and friendly way,” she says it will still be better than the stress of keeping children where the war is a threat every day.

Indeed, in some of the country’s occupied areas, Ukrainian education officials are in what some are calling a “hearts and minds” battle with Russian occupiers for those areas’ students and parents. Ukrainian officials are doing their best to make classes available online, while occupying Russian authorities are encouraging children to attend schools that will use a Russian instruction syllabus.

In the occupied city of Kherson, Russian officials are reportedly offering families new school uniforms, books, and other supplies if their children will attend school. Ukrainian forces this week launched an anticipated counteroffensive to free the city.

Kherson refugee Ms. Komarova says she’s heard about the Russians offering families 10,000 rubles to send their children to Russianized schools, but she doesn’t know of anyone taking the offer.

She’s been too focused on getting Masha settled in her new environment.

“Since the beginning of the war, it seems like life has been put on a bit of a pause,” she says. “I feel like if Masha goes to school, it will be something like normal again.”

Oleksandr Naselenko supported reporting for this story.

Lessons in survival from a bone-dry land

There’s drought, and then there’s Jordan. Lacking water all the time – their country is the second-most water-poor in the world – Jordanians rely on resourcefulness to cope with a lack of resources.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Jordanians have long learned to live without the constant running water most Americans take for granted. Water supplies are turned on one day a week for city dwellers, less frequently for many others.

The dwindling resources in parched Jordan mean the most effective innovation is not novel water distribution schemes or new infrastructure, but how people get the most out of each drop.

Um Mohamed, a mother of four in northern Jordan, heads one of thousands of households going without state-supplied water for the summer. A week’s supply from a private well costs her 15% of her monthly income. She will try to make it last one month: Used dishwater irrigates plants. Shower water is used for laundry.

The shortages are changing Jordanians’ view of charity. Fadi Al Miqdadi’s Golden Spikes Association digs rainwater wells for water- and cash-strapped families. “Cash assistance helps a family for a week, maybe two, but it isn’t a long-term solution,” he says. “A well is forever.”

Munir Asasfeh, a Golden Spikes volunteer, built a well at his home. He now shares his water with neighbors and family during the summer months. “We all need to share what resources we have,” he says. “Water is critical for life; you can’t be selfish about it.”

Lessons in survival from a bone-dry land

In towns and cities across Jordan, “water day” announces itself with a cacophony of high-pitched screeches filling the air.

Motors groan and strain to pump a trickle of water from ground-level pipes up five stories to aluminum and plastic rooftop storage tanks – tanks that will hold a family’s water for an entire week or more.

Families race to and fro across their apartments to run the pumps, do laundry, wash dishes, and water the garden before their 12-hour period is up. If they miss it, they have to wait until the next week – or perhaps weeks – for the next trickle.

“Water day is more important than an anniversary or birthday in our household,” says Um Uday, a working mother of five in West Amman. “Managing water use has become a sacred duty.”

In Jordan, the second-most water-poor country in the world, people have long learned to live without the constant running water that most American families take for granted.

Yet the dwindling resources due to climate change and population growth mean the most effective innovation in parched Jordan is not novel water distribution schemes, technology, or dam construction – but how people change their daily lives to get the most out of each drop.

With Jordanians doing more with less, their resourcefulness is reliable – even when their water supply isn’t.

In largely arid Jordan, water resources are less than 90 cubic meters (almost 24,000 gallons) per person annually, a fraction of the 500 cubic meters (about 132,000 gallons) per capita the United Nations defines as “absolute water scarcity.”

Instead of supplying constantly running water, authorities release water through networks to a given village or neighborhood for one day on a weekly or twice-monthly basis as part of a rotation.

The water distribution schedule is designed to distribute water equally in different parts of the country, without waste, while maximizing the rapidly diminishing reserves in aquifers and rainwater reservoirs.

Solutions to the dire shortage range widely across the country.

Suleiman, a retired air force officer who gave only his first name, stops his pickup at a roadside natural spring in the village of Souf, 35 miles north of Amman, to fill containers for his thirsty flock of sheep.

As they have for generations, area residents come to this spring to stock up on water for livestock or washing; a second, purer, cold-water spring 2 miles up the hill is used for drinking water.

With official water distributed to the village for a few hours once a month in the summer, these springs have become a main source.

“We get water from this spring, utilize what we have in home wells,” Suleiman says, wiping his brow from the noon sun. “We have to make the most of each water source we have.”

Tough summer

Yet this year has been particularly hard; Jordan’s Ministry of Water and Irrigation described 2022 as “the most difficult year” yet.

A shift in weather patterns means Jordan is witnessing a slight decline in rainfall. The rainfall it now receives occurs in intense, shorter time periods in concentrated areas, leaving its network of dams struggling to catch the torrential runoff.

The dams are dry or nearing dry; green patches of earth mark where once mighty reservoirs stood.

Plans to desalinate seawater at Aqaba, the nation’s only port, are two decades off at best and are costly due to the immense energy needed to pump the water 200 miles through hilly topography to Amman, where 40% of the population lives.

With the capital getting priority for dam and aquifer water, towns and villages north and south of Amman bear the brunt of shortages – often going months without fresh supplies as summer demand spikes.

Um Mohamed, a widowed mother of four in Bayt Idis, a hilly, tree-dotted village in northern Jordan, heads one of thousands of households going without state-supplied water for the summer.

On this day she purchased from a licensed private well 3 cubic meters (792.5 gallons) for $21 – enough for her family’s weekly consumption, but taking 15% of her monthly income. She will try to make it last one month.

Like many, she is sticking to tried-and-true methods to stretch out each drop.

She does the dishes in a single bucket of water placed in the sink, careful not to splash out of the bucket. Once she soaps and rinses the pots, dishes, and silverware, she pours the food-clouded water onto a few of her plants, watering in a rotation.

Showers are timed and scheduled. Laundry is hand-washed in a large plastic basin utilizing the same water.

Her backyard is dotted with jugs and buckets filled with water from her purchase; they will be used to water the plants and wash the floors over the next two weeks.

“We have entire summers where we don’t get water from authorities, so we have to rely on ourselves,” she says. “If we don’t manage what we consume, then we consume ourselves.”

Business opportunities

For buyers like Um Mohamed, there are sellers for whom the water shortage has created new business opportunities.

Even urban dwellers who subscribe to government-supplied water and who have modified their consumption habits must often resort to private-sector solutions.

Akram Adheibat and his team of six are on call 24 hours a day.

Their High Springs Water Delivery, one of dozens of water companies that have popped up across Jordan, draws water from government-licensed wells, purifies it through reverse osmosis, and delivers it to businesses and households.

Since they opened in 2014, the company has a roster of 170 subscription customers across the town of Jerash, north of Amman, while dozens more call them day or night when their taps suddenly run dry.

Households across the country rely on businesses like theirs, purchasing 20 liters of drinking water for $1.50.

“Water is a good business in Jordan,” Mr. Adheibat says, “because it is an essential need.

New view of charity

Water shortages are also changing the way Jordanians view charity; charitable associations here have long provided food packages and cash assistance to low-income families.

Fadi Al Miqdadi, who faced his own water shortages and staggering bills for private supplies, sees a solution in family-owned wells. He is urging wealthy citizens to dig deeper for charity – literally.

“Cash assistance helps a family for a week, maybe two, but it isn’t a long-term solution,” Mr. Al Miqdadi says. “A well is forever.”

His Golden Spikes Association is working to dig rainwater wells for water- and cash-strapped families across northern Jordan. It built 100 in 2021 and 18 so far this year.

The price tag for a single household well runs to $2,800, a princely sum for families living on $310 to $500 a month. Mr. Al Miqdadi’s association, which bought heavy equipment and machinery and employs a team of experienced volunteers, offers to build a well for free. It asks families to cover only the $700 in raw materials; if they cannot, the association donates the materials as well.

Each 50 cubic meter well, fed by winter’s rainwaters, is enough to provide for a family of five’s needs for three to four months, or the entirety of summer. The wells would save families hundreds of dollars each year in private water they no longer have to purchase.

Um Mohamed, a recipient of a well this summer, is waiting for winter rains to fill the reservoir for the first time.

“Water is a blessing,” says Mr. Al Miqdadi. “Jordanians are always ready to donate to build a mosque. Why not donate to improve the living conditions of families for a lifetime?”

Munir Asasfeh, a Golden Spikes volunteer, built a well at his home, which, like many in rapidly expanding villages in rural Jordan, is “off-grid” from the water network.

He says the well, his second, has given him “complete independence.” He now shares his well water with his neighbors and family during the summer months. “We all need to share what resources we have. Water is critical for life; you can’t be selfish about it,” he says. “That is what our ancestors did, and that is what we must continue to do for the good of the community.”

Monitor Breakfast

Union rebound? AFL-CIO’s Shuler sees promise, but long road ahead.

Labor unions are increasingly popular, have a friend in the White House, and see some signs of worker leverage in the job market. The AFL-CIO president says they still have a battle ahead to boost their ranks.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

A newly released poll heading into Labor Day weekend shows a near-record 71% of Americans approve of unions, up from 64% before the pandemic. Yet that Gallup Poll stands in contrast to some raw math: Just 1 in 10 workers on U.S. payrolls are union members, half the level seen four decades ago.

Liz Shuler, president of the AFL-CIO labor federation, wants to bridge that gap – by adding a million new people to union ranks over the next 10 years.

As she spoke at a Monitor Breakfast for reporters on Thursday, it was clear that for her, it is personal.

“My dad grew up in a one-room fruit picking shack in Hood River, Oregon. He and his four siblings often went hungry.” Then he found a union job as a power lineman at Portland General Electric. Beyond the pay, “it also meant dignity and respect. It meant having a voice being heard.”

She says millions of workers are reaching for those same things today.

“We would say that unions are a pillar of a healthy democracy, and we see it around the world that unions have always been sort of bedrock to the foundation of a healthy economy and a healthy society,” Ms. Shuler told reporters.

Union rebound? AFL-CIO’s Shuler sees promise, but long road ahead.

A newly released poll heading into Labor Day weekend shows a near-record 71% of Americans approve of labor unions, up from 64% just before the pandemic. Yet that Gallup poll stands in contrast to some raw math: Just 1 in 10 workers on U.S. payrolls are union members, half the level seen four decades ago.

Liz Shuler, president of the AFL-CIO labor federation, wants to bridge that gap – starting by adding a million new people to union ranks over the next 10 years.

As she spoke at a Monitor Breakfast for reporters on Thursday, it was clear that for her, it is personal. It’s about her own story, and the life stories of people she has met, some of whom leave memories that make her voice quake with emotion.

“My dad grew up in a one-room fruit picking shack in Hood River, Oregon. He and his four siblings often went hungry.” That all changed for her family in one generation, she said, because her dad found a union job as a power lineman at Portland General Electric.

Beyond the pay, “it also meant dignity and respect. It meant having a voice being heard.”

Fast-forward through the decades, and she says millions of workers are reaching for those same things today. She draws a line from hope for dignity to hope for U.S. democracy.

“We would say that unions are a pillar of a healthy democracy, and we see it around the world that unions have always been sort of bedrock to the foundation of a healthy economy and a healthy society,” Ms. Shuler told reporters.

One thing that’s clear: Some unionization drives are succeeding and emboldening many in the young generation of workers.

Ms. Shuler acknowledges ways that the labor movement can improve from within, by being “more modern and dynamic and inclusive.” She wants to see unions expand their relevance, whether by collaborating to grow their ranks or having answers to challenges like the on-the-job frustration known as “quiet quitting.”

Below are more excerpts from her responses to reporters on Thursday, edited for length.

On the goal of 1 million new union members:

Last June, we announced the Center for Transformational Organizing. We call it the CTO, and our baseline goal is to organize a million new workers because we know that growing the number of people in unions is going to create that power balance that we need to fix our broken economy. ... And it’s where we’ll get out of our silos and build a movement that is taking on very specific goals together, and particularly in nonunion areas of the economy, like gig work, like Amazon, like the clean energy economy.

On whether labor leaders can rally their diverse membership around union-endorsed candidates:

Well, that is a question that I think speaks to the moment we’re in in our country, where, you know, we have a lot of divergent views. ... We have members that certainly will disagree with candidates that perhaps have been endorsed at the local level. But those are democratic processes, right? So that it’s the members on the ground that actually make those decisions. … We are taking a different approach this year in that we aren’t flying in from the national level and basically trying to land on a community and push a particular brand of political program.

On how to get Republican politicians to listen to union concerns:

I should be clear that we do support Republicans. We support the Republicans that actually are good on our issues and are pro-union. And in fact, there’s been, I think, a conversation within the Republican Party about being more pro-worker. You know, folks like [Sen.] Marco Rubio have sounded the alarms and said this is a mistake if we think we’re going to leave the so-called blue collar worker behind, right?

On shifts at some corporations:

I use Microsoft as an example where [President] Brad Smith actually said, you know what? My workforce is talking about unionization. Maybe that’s something that I should listen to instead of fight. And so he signed the neutrality agreement with the Communications Workers of America for Activision Blizzard. ... We would argue that being in a union actually can improve your bottom line and that we can sit at a table and actually have conversations with each other and work through problems, work through issues.

On momentum, including due to support from President Joe Biden:

This is the moment because we have so much momentum. The public is pro-union. The administration is the most pro-union administration in history. And we have working people standing up, taking risks, tremendous courage against the odds because of our broken labor laws, willing to say, you know what, enough is enough.

On federal investment creating jobs:

Huge opportunities coming out of the [Inflation Reduction Act] and the infrastructure legislation and the CHIPS Act to really reclaim domestic manufacturing as an industry that is driving good jobs. And with the labor standards that we have in the legislation to make sure that we’re not low-roading these investments, our tax dollars should be used to create good jobs. And the battery is the new combustion engine.

On the top issues workers are focused on:

The issues that we hear the most about are obviously wages, but more importantly, health care, retirement security, and toxic work environments, you know, the workplace culture issues that people are grappling with. And so I think that is, as I said, universal, no matter where you work and no matter what kind of job you have.

Presidential plantation shifts telling of history to let all voices rise

How do you tell history responsibly? Montpelier, the plantation owned by President James Madison, is expanding its focus to give more equal voice to the experience of workers once enslaved there – and to their descendants.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Montpelier, Founding Father James Madison’s former home and tobacco plantation, is breaking new ground as the nation’s first museum of its kind that’s governed by descendants of the people once enslaved there.

It’s also breaking ground, literally, in the search for evidence of the community where the enslaved people lived and worked. The goal is to move away from tours focused on the manor house and to treat the history of Montpelier’s enslaved people as a responsibility equal to the history of Montpelier’s owners.

But first that history has to be found.

The staff has mapped out a giant grid and is surveying each square with metal detectors. They look for nails, coins, bullets, and other artifacts. A tobacco drying house would only need nails to support the wood and hooks to hang the leaves. So a plot of land filled with nails and hooks would probably be one of those. A home would have other items – like ceramics, animal bones, buttons, and bricks.

“If you tell a wider, more inclusive, and more accurate story, you invite more people to identify themselves with this important history,” says James French, a descendant of someone enslaved there and member of the board. “That’s a uniting force.”

Presidential plantation shifts telling of history to let all voices rise

The forest around Montpelier, James Madison’s former home and tobacco plantation, has miles of paved trails. But Larry Walker isn’t using them. Instead, he has strapped on a rucksack, laced up boots, and tucked his pants into his socks. No asphalt today – he’s ready for a walk in the woods.

For miles, he and a group of colleagues travel what feels like the opening scene in “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” adapted to Virginia history. They walk in a line, carrying sticks at eye level to catch cobwebs. Out front, Matthew Reeves, Montpelier’s director of archaeology and landscape restoration, clears a path with a machete. He even wears a fedora.

Mr. Walker and James French, another foundation board member on the mid-August hike, are descendants of the more than 300 people once enslaved at Montpelier. The two men are scouting a permanent trail in the east woods, leading past former irrigation ditches, tobacco fields, and slave quarters. It’s part of a museumwide reimagining of Montpelier’s mandate, led by the nation’s first museum of its kind governed by descendants.

This odyssey, over decades, has at times deeply tested relationships. Earlier this year, Montpelier’s governing board fought publicly over who should tell Madison’s story – part of it as Founding Father of the United States, part as an enslaver. But that fight has ended, and the museum is trying to expand Montpelier’s narrative of history. That effort has led staff beyond the big house and toward the backwoods, where artifacts of enslaved people sit undisturbed.

“For me to center the voice of my ancestor doesn’t diminish the voice of anyone else’s ancestor,” says Mr. Walker. “If anything, it amplifies.”

The rocky road toward parity

Montpelier’s staff has worked with local descendants for decades. But in 2018, the museum hosted a summit on the topic, which helped create what’s called “the rubric,” a set of standards to help sites represent descendants of enslaved people. In 2021, Montpelier made national news when the board voted to create “structural parity” with the Montpelier Descendants Committee (MDC), which was formed in 2019. For the first time at any U.S. presidential site, these descendants would equally govern the place their ancestors lived.

The agreement never took effect. Within months, members of the MDC said, the existing board was imposing conditions on their autonomy, representation, and ability to speak freely. The relationship collapsed. In March, the board voted to change its bylaws, reversing the parity decision.

“I felt a lot of grief,” says Mr. French, attending the meeting over Zoom. “But I was also sitting in the house that was built by my three-times great-grandfather who was enslaved on that very property. As always, in difficult moments, I was inspired by what they went through.”

Within days, however, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which owns Montpelier, condemned the vote. The MDC hired a lawyer and pleaded its case in the media. Multiple board members told the Monitor that certain donors threatened to withhold gifts.

By May, several board members who had voted to revoke the MDC’s authority resigned. The Montpelier Foundation elected new members and named Mr. French chairperson. A large majority currently supports the MDC, and, going forward, the plan is for the bylaws to again guarantee parity. In the meantime, the staff’s work with descendants has resumed.

Moving beyond the manor house

Even before its latest work, Montpelier had already established multiple spaces that teach about slavery. In the cellar of the manor house, “The Mere Distinction of Colour” exhibit emphasizes enslavement’s human impact. Just west of the house, visitors can enter reconstructed slave quarters that include life-size images of descendants and recorded stories of their ancestors. Museum tours teach about slavery and include specific stories of enslaved people.

That effort has mattered to visitors.

Steve Hanna, a cultural geographer at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Virginia, studies how presidential sites present Black history. At Montpelier, according to his research, visitors reported learning more about and feeling more empathy for enslaved people than at similar sites. The data has some bias: Visitors self-select into most exhibits, and the people who visit presidential sites tend to be white, as well as older, more educated, and more affluent than the average American. Before the pandemic, Montpelier had around 125,000 visitors per year. Half of those polled by Professor Hanna spent time at an exhibit related to slavery.

“It made them feel like they learned more about enslavement and were able to empathize with people who suffered, survived, and endured being enslaved,” he says.

But as is often the case at presidential sites, the visitor experience still orbits Montpelier’s big house. That’s not necessarily a problem, says Elizabeth Chew, Montpelier’s acting CEO; it’s just incomplete. Much of the site’s history is farther away and far less excavated. Unearthing it is now one of their top priorities. Parity isn’t just about equal representation for descendants, says Dr. Chew. It’s also about giving the stories of their ancestors equal weight.

Montpelier spans more than 2,600 acres and was even bigger when the Madisons were alive. Dolley Madison sold the estate in 1844, and no owner has farmed extensively there since. For the staff, that’s a powerful resource. “The ground is pristine,” says Dr. Chew. “That’s where a lot of the evidence of the lives of the enslaved lives.”

Finding the fields in the forest

Dr. Reeves and other staff members are now trying to make that evidence more accessible. It’s just hard to blaze a trail when the important sites are now covered in trees.

To discover what’s there, the staff has to search for whatever time can’t erase. Slave quarters, sheds, kitchens – none of the original structures in the fields were built to last. Still, certain pieces of them are just beneath the surface.

So the staff has mapped the entire east woods into a giant grid and is surveying each square with metal detectors. They look for nails, coins, bullets, and other artifacts, recording what they find and where they found it. The more finds in an area, the more likely that area once contained something important.

“Archaeology is in large part the study of trash,” says Dr. Chew.

A tobacco drying house would only need nails to support the wood and hooks to hang the leaves. So a plot of land filled with nails and hooks would probably be one of those. A home would have other items – like ceramics, animal bones, buttons, and bricks.

Meanwhile, all of this work can connect to Montpelier’s two fundamental missions: telling the history of Madison and the history of the enslaved people there. “Madison in essence lived in an African American community,” says Mr. French. “He was influenced as much by them as they were by him.”

“A uniting force”

In August, Susan Lange, from Annapolis, Maryland, stopped by Montpelier with her husband while in town for a wedding. Standing in the sun, wearing a hat and bright sundress decorated with palm trees, she wished her tour had lasted longer and included places like the nearby slave quarters. “It just really stood out … showing that each person was more than their enslavement, that they were a fiddle player or a mother,” she says. “Those feel like obvious statements, but [it emphasized] the humanity.”

Mr. French hopes more visitors leave with an experience like hers. There’s already been a backlash to the new board, evident in recent critical articles and online reviews describing the tour as “woke,” imbalanced, and having an “obsession about slavery.” Each of the four board members interviewed by the Monitor mentioned it. They also noted that none of the exhibits have changed; only the board has.

Standing by the decaying witness tree, sweating in his ball cap, his pants tucked into his socks, Mr. French says he hopes the site can matter to others the way it does to him. “There’s a thirst to know what is my past,” he says.

This is the place he can quench it, and to Mr. French, Madison’s home is exactly the kind of place America needs today. Montpelier nurtured James Madison, the champion of American Federalism and the Bill of Rights. He helped guarantee Americans’ individual liberties; he and his family also enslaved hundreds of people, a third of whom were children, over more than a century.

“If you tell a wider, more inclusive, and more accurate story, you invite more people to identify themselves with this important history,” he says. “That’s a uniting force.”

Books

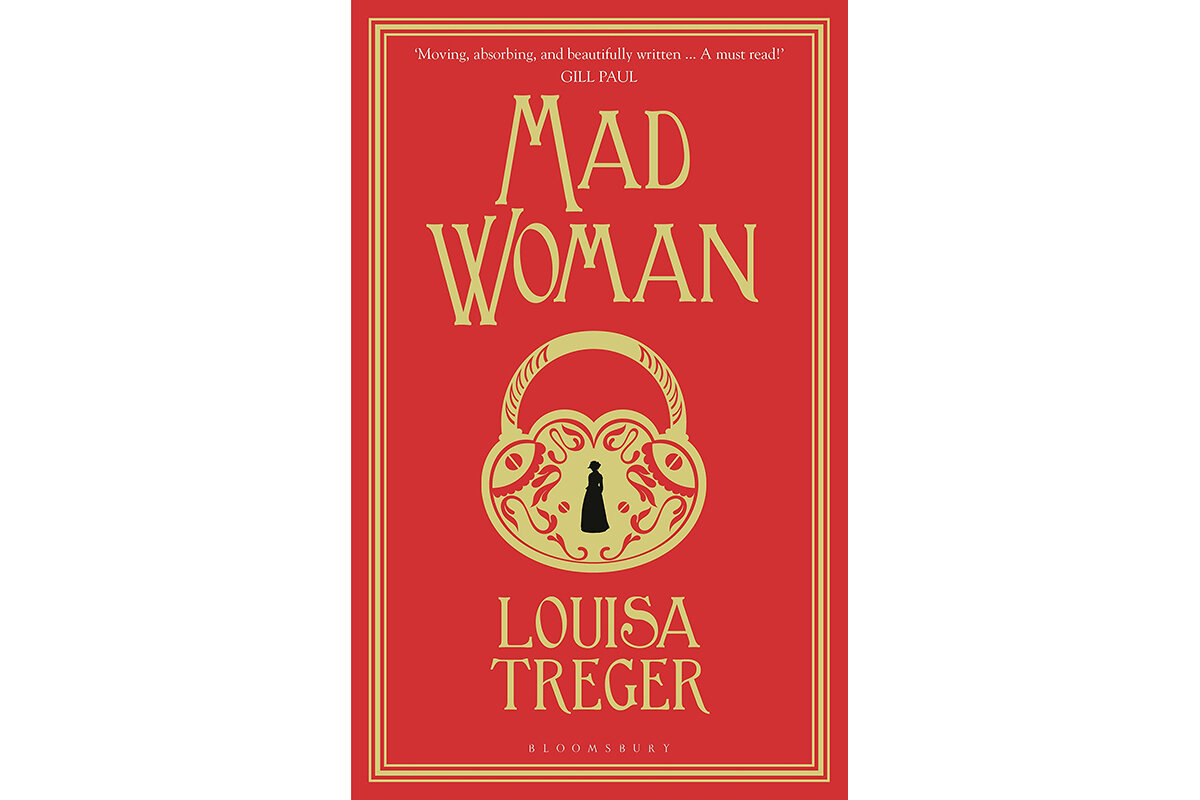

A voice that wouldn’t be ignored: Nellie Bly and the pursuit of truth

Persistence is needed to uncover wrongs and chart a course toward change. In the 19th century, a female reporter courageously put herself on the line to reveal the truth.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Samantha Laine Perfas Staff writer

“A woman can’t be a reporter” was a remark that Nellie Bly heard continuously. Her professional aspirations were not welcome; everyone from family members to sources to other journalists tried to discourage her. Yet Nellie persisted.

Her perseverance was driven by the conviction that journalism was her calling. In “Madwoman,” the new novel based on the real-life Nellie, author Louisa Treger writes of her commitment to becoming a reporter:

“It was storytelling with a difference. It involved delving into complexity, bringing gray areas of morality to light; and it was backed up by collating evidence and finding justice.”

In an effort to prove herself to the editors of the New York World, she offered to go undercover as a patient to Blackwell’s Island, home to an infamous hospital for women with mental illnesses.

The editors decided to give her a shot. The assignment turned out to be the making of her career.

A voice that wouldn’t be ignored: Nellie Bly and the pursuit of truth

At a time when trust in the media is at an all-time low, Louisa Treger’s “Madwoman” is a thoughtful reminder of how journalism can drive positive change. A work of historical fiction, it tells the story of the real Nellie Bly (1864-1922), the first female investigative reporter who not only demanded justice from powerful institutions, but also insisted on dignity and compassion for the most vulnerable citizens.

Treger deftly weaves together Nellie’s story, taking liberties with the details but cleaving to as many of the biographical facts as possible. Born Elizabeth Jane Cochran and nicknamed “Pink,” she was a spirited girl interested in playing with her brothers, listening to the imaginative tales of her mother, and reading quietly with her father, a prominent judge. Hungry for knowledge and ambitious from a young age, Nellie seemed to have it all. But what started as a charmed life quickly took a turn, as her father died unexpectedly and her mother found herself in an abusive second marriage.

The trauma and poverty that followed nearly left Nellie destitute, unable to pursue a career in law that her father once supported.

Through a series of events, rooted in her quick wit and passion, she found herself on the staff of the Pittsburgh Dispatch, writing articles that shocked the city. From there, she ventured to New York City to try her hand reporting for some of the biggest publications in the field.

Treger makes it clear that Nellie’s professional aspirations were not welcome; everyone from family members to sources to other journalists reinforced the notion that women could not be reporters. And yet she persisted. Her perseverance was driven by her conviction that this was her calling. Treger writes of Nellie’s commitment to becoming a reporter:

“It was storytelling with a difference. It involved delving into complexity, bringing gray areas of morality to light; and it was backed up by collating evidence and finding justice. Journalism reconciled the contributions of both her parents.”

The novel really takes off when Nellie must prove herself to the editors of the New York World. In a bid to get their attention, she pitched an impossible story, offering to go undercover as a patient to Blackwell’s Island, home to an infamous asylum for people with mental illnesses. The editors decided to give her a shot.

In real life, Nellie did get herself committed, endured imprisonment, and successfully reported the events she witnessed once released. It is a harrowing tale – not just that Nellie’s experience was horrific, but that she voluntarily experienced these conditions to reveal them so others might be spared. Still, it’s hard to know which events in “Madwoman” are factual and which are embellishments, as Treger warns the reader ahead of time that “where gaps exist in the records, [she] felt free to invent.” A note at the end of the novel provides Treger’s source material.

Through Nellie’s descriptions of the women with whom she was incarcerated, it becomes easy to see that “insanity” and “madness” were essentially catchall diagnoses for anyone who didn’t fit society’s expectations. Women who were unfaithful to their husbands, or who didn’t speak English, or who grieved the loss of a child were thrown into the facility with little hope of care or recovery. What’s more, the treatment was so brutal that Nellie reflects, “Here was where the madness lay – in being imprisoned in this space, trapped and caged like an animal.”

Her reports spoke of the rapid physical and mental deterioration of women in such conditions. As she says of one patient, “It was painful to watch her folding herself up and packing herself away, retreating to some place deep inside.” The novel portrays the reality that people’s mental health falls on a spectrum, and how they are treated can mean the difference between a life of agency or one of despair.

Some portions of the book are graphic; Nellie herself suffers abuse at the hands of the nurses on multiple occasions. One particular scene goes beyond physical violence into deep humiliation and dehumanization. Given these powerful portrayals, the reader comes to the same conclusion as Nellie: Something had to be done.

Her compassionate inquiry into the lives of women who were institutionalized served as a catalyst for her own efforts and agency. Her story is the perfect example of the power of an individual to question, and change, the status quo.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Flipping the script on democracy’s decline

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A current view of global trends is that the world is in a new rivalry between the United States and both China and Russia, complicated by a rise of so-called middle powers such as Turkey and India. This view also sees an erosion of free trade, international agreements, and democracy.

Yet a counternarrative is plain to see. From Africa to Afghanistan, individuals and local communities are pushing against repression and isolation, reflected in their aspirations for equality, economic opportunity, and compassion.

This drive for open, pluralistic societies may be flipping a long-standing script. During the Cold War and its three-decade aftermath, mature Western democracies sought to export their models of government. Now the civics lessons may be flowing the other way.

For many established democracies facing the strains of legitimacy, lessons for renewal can come from unlikely places. It just takes looking past the accepted narrative.

Flipping the script on democracy’s decline

A current view of global trends is that the world is in a new rivalry between the United States and both China and Russia, complicated by a rise of so-called middle powers such as Turkey and India. This view also sees an erosion of free trade, international agreements, and democracy.

Yet a counternarrative is plain to see. From Africa to Afghanistan, individuals and local communities are pushing against repression and isolation, reflected in their aspirations for equality, economic opportunity, and compassion.

“Our hands are not empty,” Shahlla Arifi, a female activist in Afghanistan, told The Washington Post after a year of frequent protests by women against the Taliban’s newly restored repressive rule. “We exposed the Taliban’s faults. We showed the world their brutality.”

This drive for open, pluralistic societies may be flipping a long-standing script. During the Cold War and its three-decade aftermath, mature Western democracies sought to export their models of government. Now the civics lessons may be flowing the other way.

“As Africans, we should realize that it is our duty to stand with the people of America and Britain,” wrote Kenyan editorial cartoonist Patrick Gathara in Al Jazeera in July, “and to support their aspirations for democracy, accountability, and transparent government.”

A bit of cheek, perhaps, but he had a point. August elections in Kenya and Angola, for example, showed that judiciaries and election commissions are gaining independence and transparency at a time when those same democratic institutions are under attack in the U.S. Zambia tossed out an incumbent last year. In Senegal, the opposition fell just two seats short of a legislative majority in the July elections; that provides an important buffer for democracy at a time when President Macky Sall has hinted at seeking constitutional changes to prolong his power.

In each of those countries, challenges to election results have strengthened the rule of law by recognizing the legitimacy of courts rather than political violence.

“Africans express a stout preference for democracy,” noted Tiseke Kasambala, director of Africa programs at Freedom House, on the organization’s website. “Young people who yearn for reform are the continent’s biggest drivers of change. ... Social movements that successfully mobilized communities have played a critical role in keeping the continent’s civic space open.”

The threats to the world’s liberal order cannot be dismissed. But neither should the gains. They are reflected in the hard-won reproductive rights secured by women’s movements in Argentina and Colombia, and in the resolve of Ukrainians to protect their democracy from Russian aggression.

That kind of courage is a powerful rebuttal to despair or “democracy fatigue,” argues Henry Giroux, professor of cultural studies at McMaster University in Ontario. It shows that there is an “opening up [to] the possibilities of thinking in a different way so that one can act in defense of the common good, equality, social justice, and democratic ideals,” he told Slate.

For many established democracies now facing the strains of legitimacy, lessons for renewal can come from unlikely places. It just takes looking past the accepted narrative.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Honoring God

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karen Neff

Worshipping God means fully honoring Deity as the only power. This author discovered that striving to honor God in her daily activities and in her approach to world issues provides practical solutions and healing inspiration.

Honoring God

One day I began to consider what makes Christian Science a Bible-based, spiritual religion and not just a self-help doctrine. I quickly realized it is because Christian Science is based on the worship of God and not on a mechanism of the human mind.

Thinking about worshiping God led me to ponder the Lord’s Prayer that Christ Jesus taught, which begins, “Our Father which art in heaven, Hallowed be thy name” (Matthew 6:9). I wondered what it means to hallow God’s name and whether I was doing that. I found that to hallow God means to honor Him as holy – as pure, immaculate, and complete.

One way to honor God’s holiness is to think about an aspect of Deity elucidated in Christian Science, discovered by Mary Baker Eddy: God’s omnipotence, or all-power. The Christian Science textbook, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” explains: “There is no power apart from God. Omnipotence has all-power, and to acknowledge any other power is to dishonor God” (p. 228).

This idea of honoring God as the only power can serve as a guide in daily life. For instance, we can ask ourselves, when we speak, if it’s in a way that is gracious and respectful and that honors God and His creation. And when we see reports of destruction, disease, and loss, do we actually dishonor God by believing He would allow these to happen? Or do we honor Him by praying to see that all of His children are being cared for?

Honoring God gives impetus to our prayers. For example, when I have felt anxious, I have prayed, “I will honor God by being calm, since I know He is upholding me.” Or once when I unexpectedly had to give a public talk, I prayed to honor God, divine Love, by letting the inspiration come from Him and not letting the talk become a self-promoting recitation. Although I’d had very little time for preparation, the words flowed, enabling me to express thoughts that I knew came from a source much higher than myself.

One healing that came as a result of honoring God was that of being excessive, especially when it came to grocery shopping. If I found an item I liked, I would buy as many as I could find or afford. This resulted in many foolish and wasteful purchases, but I couldn’t seem to stop. I felt safer when I had a supply laid up for myself and my family.

Hoarding stems from a fearful assumption that we won’t have what we need. But Science and Health states: “Divine Love always has met and always will meet every human need” (p. 494). We can honor God by trusting the divine law of Love to supply every need. In my case, I determined to resist the compulsion to overbuy through prayer – through honoring God.

The need to lean on God’s all-power to provide for every need was put to the test when the pandemic hit and I was tempted to fall into old habits and start stockpiling hard-to-get items. But I wanted to trust God’s provision, as well as love others enough to leave sufficient supplies for them. I faithfully did this, and during this difficult time, I found I was always able to get what was needed when it was needed.

Each day provides plenty of ways to honor God. And while the complete resolution of each issue may still be forthcoming, there is enough evidence of progress to encourage us to continue honoring God as the only power and source of all good.

A message of love

On your Marx, get set, go

A look ahead

Thanks for spending time with our stories today. Tomorrow, we’ll examine the enduring appeal and legacy of the children’s book “Goodnight Moon.” The article will be accompanied by a special audio component. Until then, good night, dear reader.