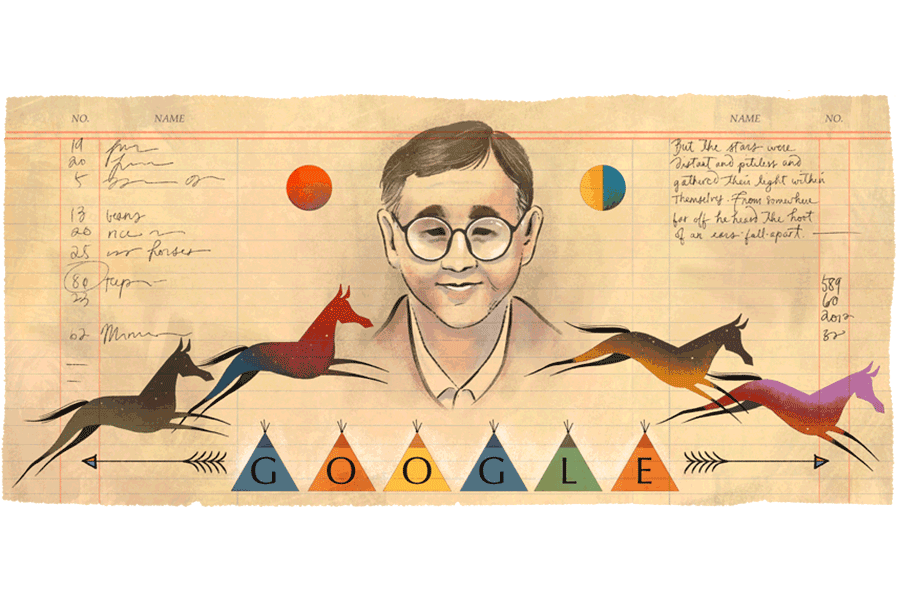

Google honors James Welch, writer of the Native American Renaissance

Loading...

There was a time when acclaimed author James Welch worried whether anyone would appreciate reading literature from a native American point of view.

“I began to think that maybe… life on the reservation was hopeless. Nevertheless, I began to write poems about the country and the people I come from,” Mr. Welch, the subject of today’s Google Doodle, once wrote.

Those concerns were put to bed long ago, after his novels and poetry based on his rich observations of life growing up on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in Browning, Mont., gained him international recognition, especially in Europe.

Now, on what would have been his 76th birthday, an image of Mr. Welch (1940-2003), who is known as a founding member of the literary Native American Renaissance, will spend the next 24 hours watching over Googlers around the world whenever they visit the ubiquitous search engine’s homepage.

Welch, whose famous works include his first book of poetry, “Riding the Earthboy Forty,” and his first novel, “Winter in the Blood,” is being recognized at a time when long-marginalized native American communities are pushing to the forefront of national consciousness in ways that he may not have imagined.

For one thing, President Obama will next week posthumously bestow the Medal of Freedom on Elouise Cobell, a leader of the Blackfeet tribe and advocate for native American rights.

But more prominently, for months now, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of North Dakota and others from around the nation, backed by various celebrities, have garnered international media attention in their persistent protests against the construction of the Dakota Access pipeline.

“There’s an awakening happening now ... and First Nations around the world are leading that awakening,” Joseph Hock, a native American protester at Standing Rock, told The Christian Science Monitor earlier this month.

As the protesters, at least some of whom prefer to be referred to as “water protectors,” continue to blockade the site where the DAPL is proposed to pass under the Missouri river, they see the native American stance against the pipeline and broader environmental issues as relevant far beyond their immediate context.

“The issues are resonating throughout Indian country, throughout indigenous peoples, throughout the world,” says Bob Gough, secretary of the Intertribal Council on Utility Policy.

“Indigenous people around the world are taking a stand in a time of rapidly accelerating climate change,” he told the Monitor. “This becomes the tip of the spear, the case in point of where the fossil fuel industry is threatening life itself.”

Welch’s work was described by The New York Times at the time of his passing as “exploring the complex relationship between his origins and the world outside.”

“Happily, I was wrong in thinking that nobody would want to read books written by American Indians about American Indians and their reservations and landscapes,” Welch once wrote.