Election week could be just as long, and fraught, as in 2020

| Washington

During election week 2020, Seth Bluestein never went to sleep.

Mr. Bluestein, then Philadelphia’s chief deputy election commissioner, woke up on Election Day to oversee the tallying of hundreds of thousands of votes. The next time he got some shuteye was three days later, on Friday.

“We knew that we had to continue counting, 24/7, until every ballot had been canvassed, and that’s what we did,” he says.

Why We Wrote This

Delayed election results can open the door to suspicion and disinformation. Yet in a close election, a dayslong wait to know the winner isn’t surprising. It happened in 2020. We look at why it could easily happen this year, too.

As he worked, he came into the crosshairs of the Trump campaign, which falsely claimed that their candidate had won the state and that something fishy was going on in Philly. After a Donald Trump surrogate criticized Mr. Bluestein by name during a press conference, antisemitic messages and death threats poured in.

“We had to get police protection outside of my house to protect my wife and kids while I was at the convention center counting ballots,” says Mr. Bluestein, who is now the Republican commissioner on Philadelphia’s election board. It took until Saturday before enough ballots were counted for news networks to call the state – and the election – for Joe Biden.

Steps could have been taken to lower the risk of a repeat scenario for 2024. But the state’s GOP-controlled legislature refused to heed bipartisan pleas to let officials process mail votes before Election Day, meaning it will still take days to tally all of those results. That could lead to another drawn-out election with no clear winner for days.

And delays leave a void for bad-faith actors to step in and attack the system.

“The window of time from when the polls close until the race is called is the largest window for mis- and dis-information and harassment and threats,” Mr. Bluestein says.

First, the good news: Vote counting will likely go faster in most states this time around. The country is no longer conducting an election at the height of a global pandemic, so fewer people are opting to vote by mail, based on early 2024 mail ballot requests and returns. Mail votes simply take much longer to count because those ballots require many additional steps of verification and preparation. And some swing states have taken steps to improve election law to speed up the vote-counting process.

But the four crucial battleground states of Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Arizona, and Nevada all will likely take a while to fully tabulate their returns. If the race is as close as polls suggest, that will likely leave America waiting for days to know who their next president will be, in a highly fraught election that many voters from across the political spectrum feel is an existential turning point for the country.

Election disinformation has already picked up in intensity. Last week, a video went viral purporting to show someone destroying Republican mail ballots in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, a critical swing county. State and local election officials quickly showed that that video was fake – but not before it racked up hundreds of thousands of views on the social platform X. U.S. intelligence officials said Friday they believe it was a Russian disinformation effort.

Slow counting is frustrating, but it isn’t an actual problem. The challenge comes when high-profile politicians such as Mr. Trump cast aspersions on a process that, while slow, is overwhelmingly accurate. In the aftermath of the 2020 election, the former president declared victory on election night even as millions of votes remained to be counted, tried to overturn his election loss for months, and has continued to insist, with no evidence to back his claims, that he won – while refusing to promise he’ll accept the results this time.

On Friday, Mr. Trump posted on his social media about the supposed “Cheating and Skullduggery” of the 2020 election – while warning about 2024. “WHEN I WIN, those people that CHEATED will be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the Law, which will include long term prison sentences so that this Depravity of Justice does not happen again,” he posted.

“If Donald Trump perceives that he is losing … I think we’re likely to hear him declare victory on election night and spread lies about the election,” says David Becker, a former Justice Department Civil Rights Division attorney who heads the nonpartisan Center for Election Innovation & Research.

The slow climb up the “Blue Wall”

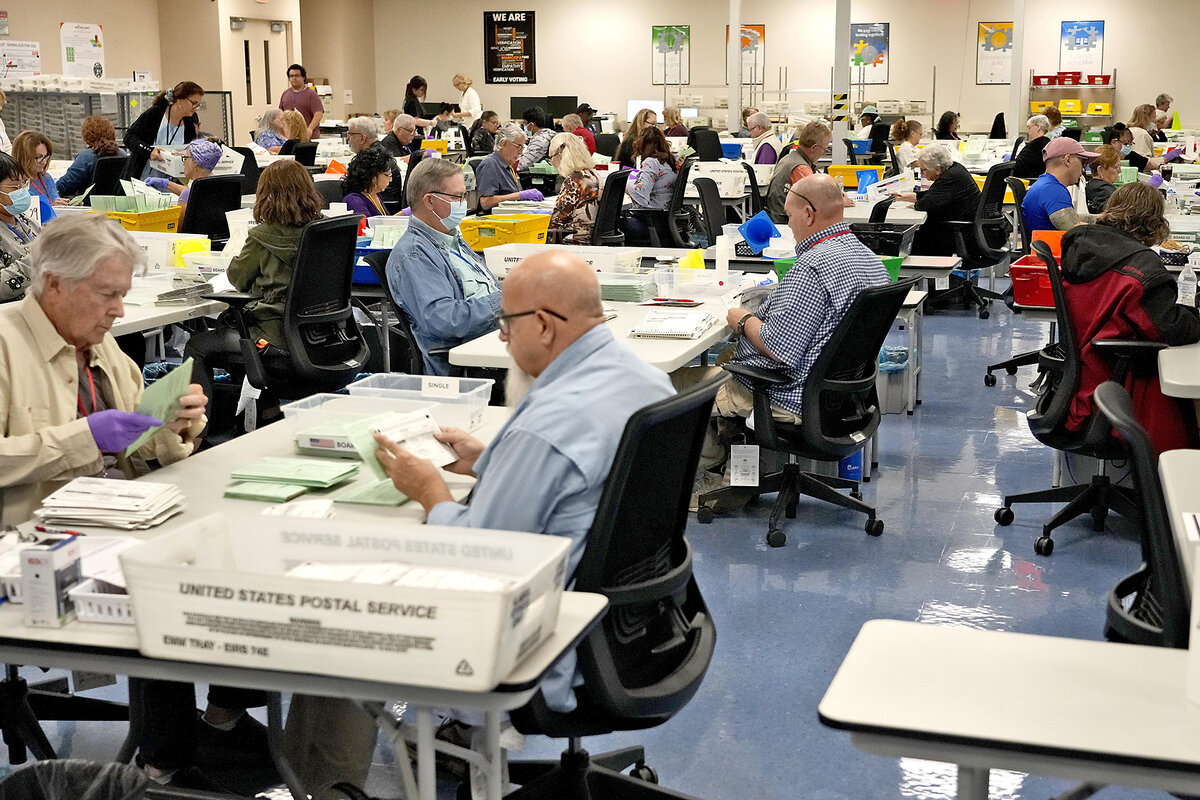

Forty-three states allow county election officials to begin pre-processing mail ballots before Election Day: checking to make sure the ballots are valid, removing them from envelopes, smoothing them out so they can go through tabulating machines (but not counting the votes themselves). That lets those states move vote-counting along at a faster pace on Election Day.

But Pennsylvania and Wisconsin are exceptions, which slows downvote counting in two states that have been pivotal in the past two presidential elections.

On top of that, neither state has in-person early voting, meaning the only way to vote before Election Day is by absentee ballot. (Wisconsin has “in-person absentee voting” where people can vote absentee ballots at election sites). That means those states have many more absentee ballots to process than other states.

Former Kentucky Secretary of State Trey Grayson, a Republican, says it was “really unfortunate” that Pennsylvania didn’t change its law to allow pre-processing of ballots.

“When you start having a lot of people vote by mail, you really do need the pre-process. Otherwise, your results aren’t going to come in as quickly,” he says.

In Pennsylvania, Republicans refused to pass legislation allowing pre-processing unless Democrats first expanded the state’s voter identification requirements. In Wisconsin, a bill to allow pre-processing passed the GOP-controlled Assembly with bipartisan support but was stonewalled by hardline Republicans in the state Senate.

The counties that tend to take the longest to count their ballots are invariably large urban areas, which tend to be racially diverse and heavily Democratic – places like Philadelphia and Milwaukee. That’s largely because so many more votes come in that it takes longer to accurately tabulate them all. But it feeds into racially tinged conspiracy theories that local Democratic machines are rigging the vote. Milwaukee has new vote-counting machines that can tabulate 100 ballots a minute, a big improvement over the old machines that could only process seven ballots a minute in 2020 – but the main bottleneck is physically verifying the votes and preparing them for the machines.

“If Milwaukee gets their results in by 2 a.m. [CST], I’d be delighted,” says Ann Jacobs, a Democrat and the chair of the bipartisan Wisconsin Elections Commission.

“We’re going to have late results that will result in significant numbers coming in all at once – and that significant number all at once will be from largely Democratic-leaning communities … our larger urban areas,” she continues. “It’s math.”

Ways that counting has improved since 2020

Michigan used to be in the same boat. But the state is likely to count its votes faster this time around. In 2022, voters passed a state ballot initiative that is allowing in-person early voting for the first time. While early counts of in-person early voting have been relatively low, voters who cast their ballots that way rather than through the mail make it easier on county clerks to tally the votes. On top of that, Democrats who control the state’s legislature and governorship passed a law allowing pre-processing of ballots, meaning they’ll be able to move mail votes much faster.

In Georgia, which has always counted its votes relatively quickly, lawmakers and elected officials have put a major emphasis on speeding up the count – Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger told the Monitor last month that the goal is “free, fair, and fast.”

State courts also struck down a bevy of controversial last-minute election rule changes pushed through by hardline conservatives on the state election board, including one that would have slowed down the state’s vote count by forcing poll workers to hand-count the number of ballots cast in every county on Election Day.

We’re likely to see the same “red mirage” as last time in a number of states that process their mail ballots later than in-person ballots. Preliminary early voting numbers across various states show that registered Democrats are still voting by mail at a much higher rate than Republicans this election, though in smaller numbers than 2020. In the states like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, where those Democratic-leaning batches are counted last, that means early numbers will appear better for Mr. Trump than the final result. And in states like Nevada and Arizona where mail voting is dominant, it will simply take much longer to tabulate ballots, something that’s been true long before the Trump era.

How the West was mailed

Most Western states of all political persuasions have adopted predominantly mail voting elections over the past two decades, making their vote-counting take longer.

Hotly contested Arizona is a heavily vote-by-mail state that for decades has taken a long time to count its ballots – long enough that it has regularly taken days and even weeks to know who won close elections. Former President Trump has used that slow process to cast doubt on the results for years. In 2018, as Republicans were on their way to losing a close Senate race during vote-counting after Election Day, Mr. Trump falsely claimed “electoral corruption.”

Arizona officials, unlike workers in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, can preprocess mail ballots. But they can’t begin processing ballots dropped off on Election Day until polls are closed. And since many voters are in the habit of hanging onto their ballots until the last minute in the state, it leads to a significant slowdown.

Nevada is also likely to take a while. As in 2020, it has sent mail-in ballots to every active registered voter in the state, which will likely increase mail voting over in-person voting. Nevada also counts mailed ballots received up to four days after the election, so long as they were mailed by Election Day.

“Depending on margins [of victory], my expectation would be Arizona and Nevada are the states that we’re waiting on the longest to find out a call about the election,” says Derek Tisler, a counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice’s Elections and Government Program.

He says that if the margins of victory in key states are as close as they were in 2020, it will likely take about as long as it did four years ago to know who won. If the race is significantly closer, “it will likely be weeks before we know who won the presidential election.”

And that worries him.

“What we saw in 2020,” he says, “is the longer the time is between when voters finish casting their ballots and when we know who won the election, the more opportunity there is for disinformation about elections to spread.”