- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Democrats’ big problem: How to win without Trump to run against

- Much of Africa still lacks electricity. The carbon ethics are thorny.

- Climate summit: The key is momentum, even if progress is slow

- Why the Hindu Festival of Lights is spreading around the world

- It’s bleak, bloody, and No. 1 on Netflix. How ‘Squid Game’ won the pandemic.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

New York City vaccine mandate: A tale of public worker rebellion?

Some 2,300 New York City firefighters didn’t show up for work Monday, taking “sick leave” rather than get vaccinated.

The city had issued an ultimatum to all employees: Get vaccinated or risk losing your job. The mandate is “causing an exodus” of firefighters, warned the president of the Uniformed Firefighters Association.

The Big Apple firefighter “sickout” sounded like this might be a political uprising for personal liberty, but one that was risking public safety. What if a fire broke out and no one showed up? The situation seemed to be fueling fears and feeding a larger narrative of polarization.

If you look a little closer, the numbers tell a more nuanced story.

Police, firefighters, and municipal employees aren’t spearheading a rebellion. Most are calmly complying.

Overall, 92% of the city’s employees have received at least one vaccine dose – well above the rate among adult New York City residents. The vaccination rate among New York City police officers is at 85%, up from 70% two weeks ago. The vaccination rate of firefighters was 77%, up from 58% on Oct. 20, say city officials. And that “exodus” of 2,300 firefighters on “sick leave”? That’s only about twice the normal sick leave rate.

Yes, some 9,000 city employees – from police to sanitation workers – have been placed on unpaid leave for not getting vaccinated. Again, that sounds like a big number. But it’s less than 3% of the total city workforce. And out of that 9,000, only 89 police officers (out of 35,000) had been placed on unpaid leave as of Tuesday.

It’s a reminder of the need to delve beneath the headlines for the facts. The situation is still unsettled, but the dangers and stakes need to be calibrated honestly. What could look like a rebellion against government tyranny on closer scrutiny looks more like a story of law-abiding workers doing their best to navigate difficult choices.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Democrats’ big problem: How to win without Trump to run against

In the latest Virginia elections, as well as American elections generally, we look at the role of negative partisanship. It’s when voters are more motivated by what they dislike in an opponent, than what they like in their own candidate.

Democrats had some blockbuster years in Virginia during Donald Trump’s presidency.

So in this year’s gubernatorial race, Democratic candidate Terry McAuliffe hewed to a familiar message: A vote for Republican Glenn Youngkin, he said, would be a vote for Mr. Trump.

It didn’t work. On Tuesday, Mr. Youngkin captured the governor’s mansion, reflecting a dramatic shift statewide in the GOP’s direction. The swing was even bigger in New Jersey, where Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy was clinging to a narrow lead.

Antipathy toward an opposing party has frequently proved a better motivator for voters than affection for their own, a phenomenon known as negative partisanship. In recent years, Democrats found opposition to Mr. Trump to be an extremely powerful force for turning out their base. Now, President Joe Biden’s plummeting approval ratings are giving Republicans an edge.

With the 2022 midterm elections coming, analysts say Democrats will need to sell voters on their own vision and accomplishments. Still, in an era dominated by negative partisanship – in which Americans seem caught in a nonstop cycle of rejecting whichever party is in power – that’s not an easy task.

“It’s tough to be the ‘in’ party when voters are in a sour mood,” says Alan Abramowitz, a political scientist at Emory University.

Democrats’ big problem: How to win without Trump to run against

Democrats had some blockbuster years in Virginia during Donald Trump’s presidency.

In 2017, Ralph Northam won the governorship by almost 9 points, more than tripling former Gov. Terry McAuliffe’s margin from four years earlier. Democrats flipped three of the state’s 11 congressional seats in 2018, and in 2019 took control of the state legislature for the first time in over two decades. In 2020, President Joe Biden won Virginia by 10 points.

So in this year’s gubernatorial race, Mr. McAuliffe, the Democratic nominee, hewed to a familiar message: A vote for Republican Glenn Youngkin, he said, would be a vote for Mr. Trump.

It didn’t work.

On Tuesday night, Mr. Youngkin captured the governor’s mansion here, in a 2-point win that reflected a dramatic shift statewide in the GOP’s direction. Republicans also appeared poised to take control of the Virginia House of Delegates. The swing was even bigger in New Jersey, where Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy was clinging to a narrow lead in a state that elected Mr. Biden by 16 points. As of deadline, that race remained too close to call, according to the Associated Press.

The results can be attributed to everything from historic trends to candidate quality to a national mood clouded by the pandemic and economic woes. But it was also the first time in four years that both parties found themselves campaigning in a political universe where Mr. Trump was no longer at the center of things. And his relative absence appears to have helped Republicans – and hurt Democrats.

Antipathy toward an opposing party’s candidate has frequently proved to be a better motivator for voters than affection for their own, a phenomenon known as negative partisanship. In recent years, Democrats found opposition to Mr. Trump and his bombastic style of politics to be an extremely powerful force for turning out their base. But with a few exceptions, that effect now seems to have waned, and it’s President Biden’s plummeting approval ratings that are instead giving Republicans an edge.

As both parties look ahead toward the 2022 midterm elections, analysts say Democrats will need to sell voters on a more positive message that focuses on their own vision and accomplishments. Still, in an era dominated by negative partisanship – in which Americans seem caught in a nonstop cycle of rejecting whichever party is in power – that’s not necessarily an easy task.

“Negative partisanship worked great for Democrats when Trump was in the White House,” says Alan Abramowitz, a political scientist at Emory University and author of several papers on negative partisanship. “But Republicans were much more motivated to turn out and vote than Democrats this year. ... It’s tough to be the ‘in’ party when voters are in a sour mood.”

A vote against, not for

Historically, the party that loses the White House often does well in off-year elections. Following Mr. Trump’s win in 2016, Democrats captured seven gubernatorial seats previously held by Republicans and gained a net total of 40 seats in the U.S. House in 2018. Indeed, Virginia, which holds gubernatorial elections in the year following every presidential race, has only once elected a governor from the sitting president’s party in the past 45 years: Mr. McAuliffe in 2013, after then-President Barack Obama was reelected to a second term.

Voter enthusiasm – or a lack thereof – was clearly on the minds of Democrats in the final days of the race. Campaigning for Mr. McAuliffe in Richmond 10 days before the election, Mr. Obama used the word “tired” 17 times in his 30-minute speech.

“Look, I know a lot of people are tired of politics right now,” the former president said. “We don’t have time to be tired. What is required is sustained effort.”

Mr. Biden’s current approval rating is hovering around 42% – lower than any president at this point in his first term other than Mr. Trump. Early exit polls in Virginia found that 28% of voters cited opposition to Mr. Biden as a reason for their vote, compared with 20% who cited support for the president.

In 2020, Mr. Biden didn’t generate particularly high levels of enthusiasm among Democratic voters, but that hardly mattered: Their anger with Mr. Trump was more than enough to bring them to the polls. According to a January 2021 Pew Research poll, two-thirds of voters said excitement to vote against Mr. Trump was a “major reason” for the outcome – more than double the share of voters who said Mr. Biden won because he ran a better campaign.

Some experts see the 2016 election as a hinge point in moving the nation’s politics toward a more permanently negative framework.

In that year’s presidential race, both parties’ candidates were among the most disliked in history, according to polls. Many Republican voters didn’t especially like Mr. Trump but voted for him out of strong opposition to Hillary Clinton, and vice versa for Democrats. And while that campaign may have been an anomaly, it changed the political landscape in ways that have lingered.

“Many political pundits kind of assumed it would go back to politics as usual once Trump was gone,” says Alexa Bankert, a professor of political psychology at the University of Georgia who studies negative partisan identity. Instead, “negative partisanship is here to stay, because it has proven to be such a successful campaign strategy.”

Education, economy dominated turnout

Of course, negative feelings toward President Biden – or less-negative ones toward Mr. Trump – don’t fully account for Mr. Youngkin’s win.

The former private equity executive and first-time political candidate ran a strategic campaign that was a good match for his state. He accepted a Trump endorsement and was careful not to disparage or insult the former president. But he also kept Mr. Trump at arm’s length, never campaigning with him in person and subtly distancing himself in a variety of ways. He focused heavily on education as a way to peel off moderate suburban voters who had drifted away from the GOP under Mr. Trump. Exit polls indicated education was the No. 2 issue for Virginia voters, after the economy.

In the final month of the campaign, almost 80% of Mr. Youngkin’s advertisements mentioned schools or education, according to the ad tracking firm AdImpact. Comparatively, almost half of Mr. McAuliffe’s advertisements in the last month mentioned Mr. Trump; he spent more money on advertisements about Mr. Trump than any other topic, including COVID-19, education, and the economy.

Mr. Youngkin effectively flipped the suburbs, winning them overall by a margin of 53% to 47%, after Mr. Biden won them by 53% just last year.

The suburban vote on Tuesday was not a monolith – and there’s some evidence that Mr. McAuliffe’s efforts to tie Mr. Youngkin to Mr. Trump actually worked as intended in certain spots. In the northern Virginia suburbs outside Washington, Mr. McAuliffe almost matched Mr. Biden’s 40-point margins. Although Mr. Youngkin narrowed the gap in Loudoun County, shrinking the Democrats’ 25-point win in 2020 to an 11-point victory Tuesday, Mr. McAuliffe still outperformed himself there, more than doubling his winning margin from 2013.

By contrast, in suburbs outside the beltway of Washington politics, Mr. McAuliffe struggled. Mr. Youngkin handily flipped Chesterfield and Virginia Beach counties after both had gone for Mr. Biden by several points last year.

Perhaps even more impressive, Mr. Youngkin outperformed Mr. Trump in rural areas, surpassing the former president’s double-digit margins in southwest Virginia’s longtime Republican counties.

“Youngkin was able to make himself appealing enough in suburban places, but primarily he really benefited from the environment,” says Kyle Kondik, managing editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball at the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics. “The primary driver here is the national dynamic.”

Tuesday’s results have already brought finger-pointing to Washington, with some moderate Democrats blaming Mr. McAuliffe’s loss on progressives holding up the bipartisan infrastructure bill, and with progressives blaming a few Democratic senators who have taken issue with the president’s big social spending bill.

“Now that Trump as this unifying force may no longer be in the foreground, we may see a crack in Democrats’ partisanship,” says Ms. Bankert.

Approval for congressional Democrats has already nose-dived in recent Gallup polling, from a 55% approval rate in September to 33% in late October. In many ways, it’s reminiscent of 2009 – the last time Democrats had trifecta control of the White House, Senate, and House, and when party infighting was high as Democrats worked on passing the Affordable Care Act. Democrats lost the Virginia governorship that year. And in the following year’s midterms, the party lost control of the U.S. House.

But even passing both bills now may not be enough, say some experts.

“If Biden can get his approval rating back up above 50, that will help Democrats in the midterms. But that will rely on improving the economy, keeping COVID cases down, and passing their agenda,” says Mr. Abramowitz. “To turn out voters now, Democrats need to show their ability to govern more effectively.”

A deeper look

Much of Africa still lacks electricity. The carbon ethics are thorny.

The moral trade-offs involved in curbing climate change look very different in a Senegal village with no electricity. The view of climate justice from rural Africa.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Just as much of Africa skipped landlines and adopted cellular phone service, could it leapfrog fossil fuels and bring electricity to remote areas using solar microgrids and other green sources? It’s possible, but energy experts say it would hinge on a surge in new money for such projects.

And for now, many African nations have fossil fuel reserves that can serve as a source of both domestic energy and export revenue.

This question cuts to the heart of climate justice, the idea that countries that industrialized first on the back of oil and coal owe a moral obligation to those that didn’t and are now being asked to abstain from doing the same.

A priority at the global COP26 climate summit now underway in Scotland is to secure a long-awaited $100 billion a year in commitments for “climate finance” from rich nations to poorer ones.

In rural Bakakack, Senegal, students at the local school have a hard time studying once the sun goes down. “We don’t reject solar,” says Modou Gueye, the school director. “But we want electricity first.”

Much of Africa still lacks electricity. The carbon ethics are thorny.

Aby Ndour starts most days the same way: She wakes up, gets dressed, and treks through bean and millet fields to collect firewood from the trees and shrubs scattered across the sandy countryside that surrounds her village.

Inside the small hut in her family compound where she cooks is a wood-fired stove, which is hot and smoky. At night, fires are the main source of light in Kourty; the nearest town with reliable electricity to charge a phone is four miles away.

As a result, life tends to grind to a halt when the sun goes down. Even within the village – and especially along the narrow, swerving roads to other settlements – darkness breeds wariness. “Nobody goes anywhere” after sundown, Ms. Ndour says. “We stop. It’s not safe.”

Ms. Ndour’s situation isn’t unusual. According to World Bank figures, 30% of Senegal’s population lacks access to electricity – a proportion that rises to more than 50% in its rural hinterland. Of the estimated 770 million people worldwide living without electricity, three-quarters are in Sub-Saharan Africa.

As world leaders gather in Glasgow, Scotland for the COP26 United Nations climate change conference, the urgent need to switch from dirty to clean fuels will dominate the talks. But that’s a conversation largely geared toward countries where a national electrical grid is a given, and the debate is over how quickly to decarbonize energy systems so that fossil fuels are phased out.

For lower-income countries that are still building out their grid and are late to the fossil fuel party, the debate feels very different. In Senegal, a country of 17 million in West Africa, the government is both promoting renewable energy and planning to drill more offshore natural gas. This way it hopes to power more homes and businesses and grow its modest economy.

And if the gas it burns adds a smidgeon more carbon to the global commons, who are rich countries to deny Senegal’s right to pollute? This question cuts to the heart of climate justice, the idea that countries that industrialized first on the back of oil and coal owe a moral obligation to those that didn’t and are now being asked to abstain from doing the same.

This is especially resonant when the rich world isn’t ponying up the necessary funds to pay for a green energy revolution in Africa, argues Henry Batchi Baldeh, director of power systems development at the African Development Bank.

“Use the energy resources that God has given you,” he says, referring to oil and gas deposits. “Make your own contributions to achieve net zero – but develop your economy, improve the lives of your people using those resources.”

Progress in Glasgow – will it reach Global South?

At the COP26 summit, one of the urgent questions is whether rich nations will boost their pledges – and follow through – to aid the rise of clean energy in places like Senegal.

On Wednesday, leaders at the summit reported being close to pulling together a $100 billion commitment from advanced nations – a target set in 2009 and seen by developing nations and many policy experts as an annual minimum to address the need. In addition, firms representing 40% of the world’s private capital pledged to make climate change a central priority in their lending and investment. Energy experts say a key test will be whether such commitments are felt in developing nations any time soon.

The dilemma over fossil fuel extraction in countries like Senegal goes beyond laying power lines in rural areas. Oil and gas exports are a source of finance for other national goals, says Zaheer Fakir, a senior adviser to South Africa’s environment ministry.

“Many of the developing countries are finding at this time gas or oil or other resources, which for them, they see as potential revenue streams to finance development – which developed countries have already exploited to get where they are now. The challenge now is that they’re being told to keep that in the ground,” he says.

One possible solution lies in the rapid buildout of renewables like solar and wind in off-grid regions that aren’t served by conventional energy sources. Just as much of Africa skipped landlines and adopted cellular phone service, so the logic goes, it could leapfrog fossil fuels and go green. But that, in turn, hinges on a surge in new money for such projects.

“There’s not a lack of money out there, but a lack of finance that would flow to developing countries” for renewables, says Mr. Fakir, who is working with counterparts from other developing countries to lobby for significant increases in climate financing at COP26.

Among those pledging more so far: U.S. President Joe Biden said in September that the U.S. would double its contribution.

Many countries have adopted net-zero targets by midcentury. And fossil fuel investment is falling. China has pledged to stop funding new overseas coal plants. University endowments and big banks are under pressure to divest fossil fuel assets.

But the renewables market hasn’t yet caught up with demand, and shortages of natural gas have been roiling energy markets in Europe and Asia this year, raising fresh concern over the bumpiness of a transition to green energy systems.

“A very unequal world”

For now, the transition has become a game of who gets to use up the remaining carbon budget that scientists say humanity must not exceed in order to prevent catastrophic changes to the earth’s climate. To limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels at current rates of emissions, this budget could be used up in the next decade, analysts say.

Africa is responsible for roughly 3% of current global emissions and even less of historical emissions. That discrepancy, says Janos Pasztor, a former U.N. assistant secretary-general for climate change, makes it hard for the U.S. and other major emitters to block developing countries from receiving a proportionate share of the remaining carbon budget.

“We live in a very unequal world. Let’s not forget that. There are countries that are more equal than others. This is reality,” he says.

What would this look like in Senegal? It would mean an expansion in natural gas, which has lower carbon emissions than coal and oil and has been promoted as a bridge fuel toward a low-carbon economy. BP and other oil majors are expected to begin tapping Senegal’s offshore gas, with support from the World Bank, and build onshore liquefaction facilities.

“The first impact of this [oil and gas] discovery will be to have energy everywhere, for the whole population,” said Fatou Thiam Sow, an official at Senegal’s Ministry of Oil and Energies told a conference in September. “The resources that we have should permit us to improve the living conditions of our population and accelerate our economy.”

The risk for Senegal and other latecomers to hydrocarbon exports is that demand could falter if renewables grow at exponential rates over the next few decades. Still, even the most ebullient forecasts for technologies like electric cars have room for gas-fired vehicles, particularly in Africa where charging stations are likely to be limited to major population centers. And the International Energy Agency projects a near-term increase in global demand for natural gas.

A leapfrog opportunity

For decades, landline phones failed to take off in much of Africa because of a lack of infrastructure. In the past two decades, though, mobile phone use has exploded through the spread of cell towers and cheap handsets.

In some countries, the same leapfrogging is happening in the energy sector. In Senegal, a few solar farms dot the interior, and a wind farm lies on the northern coast. The World Bank estimates that 32% of energy consumed in Senegal comes from renewable sources.

In Kenya, that share is over 70%, though it includes biomass, which would count the wood Ms. Ndour collects each morning. Still, even as it has scoped out offshore oil deposits, Kenya has expanded its generation of electricity from hydro, wind, and solar. Renewables already serve millions of rural and urban residents in countries like Kenya, Tanzania, and Ethiopia.

PEG Africa, a solar energy company in West Africa, began by providing basic electricity to households that otherwise wouldn’t likely be hooked up to the grid anytime soon. This mostly meant powering lights in villages, but advances in solar power have now made refrigerators, fans, and televisions viable in off-grid villages, says PEG co-founder Nate Heller. While the company has tapped into West Africa’s rural, middle-class market, to hook up less affluent households would require government subsidies, he adds.

“The dream is that the government sees this as a way that they don’t have to expand the fossil fuel grid to rural households, many of whom it’s not economical [to extend to] because they’re too far out, and the population of the village is too small.”

A village without access

In Bakakack, a stone’s throw away from Ms. Ndour’s residence in Kourty, a solar panel is visible adorning a nearby roof. It’s one of the expensive, finicky, private home set-up panels that are for sale in markets across the country, residents say – and it’s too weak to power much more than a cell phone or lightbulb, and not nearly enough to be a long-term solution.

Students at the local school have a hard time studying once the sun goes down. The director, Modou Gueye, has to go into town to make photocopies of exams. Farmers in Bakakack and Kourty have to travel into town to use electric-powered machines to grind their millet and other crops. The local health facility has a hard time attracting workers.

Then there are the daily indignities, residents say – not being able to have a cool glass of water after a hot day in the fields, or sleep under the breeze of a fan.

“If there was electricity, we’d prepare madeleines, we’d prepare our coffee – at a big, nice spot, cooking and selling all night,” says Ms. Ndour.

Residents here are well aware of climate change. “Everything that we know is bad for the environment, I don’t want to continue with that,” says Sada Gueye, a farmer.

Like other residents, he’s open to renewables – but more important than where the village’s future electricity comes from is that it exists at all.

“We don’t reject solar,” says Modou Gueye, the school director. “But we want electricity first.”

Staff writer Simon Montlake contributed to this article from Boston.

This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.

Patterns

Climate summit: The key is momentum, even if progress is slow

Success at COP26 or not, our London columnist observes, global support for renewable energy has shifted significantly since the Paris climate summit six years ago.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

It’s true that the political outlook for a landmark deal at the current United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland, is not bright. World leaders seem too divided.

But that is by no means the whole picture. Since the last major climate summit six years ago in Paris, much has changed, and for the better. For a start, there has been a dramatic worldwide spread of the sense that we are facing a climate emergency – not just a climate crisis – that demands action.

At the same time, renewable energy technology is becoming ever cheaper and more common.

The world’s overall direction of travel has shifted decisively toward lower-carbon energy. Last month, for the first time, the top-selling car in Britain and the European Union was not a Ford or a Hyundai – it was a battery-powered Tesla.

Even the bankers are getting on board. On Wednesday, a coalition of the world’s leading banks and finance groups announced that it would make environmental sustainability its new standard for investing.

These steps add up, even if there is no breakthrough in Glasgow. As Greta Thunberg said before the summit, “It’s never too late to do as much as we can.”

Climate summit: The key is momentum, even if progress is slow

There are two ways of looking at the crucial climate change conference currently underway in Glasgow, Scotland.

Through the narrow lens of politics – gauging the prospects of a landmark deal to make good on the unfulfilled promise of the 2015 Paris Agreement – the picture looks distinctly unpromising. Even the summit host, the habitually bullish British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, has rated the chances of success at just 6 out of 10.

Yet a wider-angle view, taking account of what has changed since Paris, yields a decidedly different picture. There has been a dramatic worldwide spread of the sense that we are facing a climate emergency – not just a climate crisis – that demands action; meanwhile, cleaner, greener energy technology is more and more common.

All that may get overshadowed in the coming days by the diplomatic drama in Glasgow. Understandably so. The goal of the Paris summiteers to cap global warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels has been receding. The national targets announced so far by some of the world’s leading economies – especially China, the largest carbon emitter – are nowhere near enough to turn that around.

But the wide-angle view matters, too. And it will be especially important to keep in mind if the Glasgow summit ends as expected, short of a full diplomatic breakthrough, but with enough new commitments to create what U.S. climate envoy John Kerry has called a “critical mass” of momentum for more ambitious action in the months that follow.

Because there are growing signs that the world’s overall direction of travel has shifted decisively toward lower-carbon energy. It’s a trend even China recognizes, indeed one that it is leading. Although Beijing is not yet ready to cut back dramatically on its use of coal – around half the world’s total – it has also been investing in huge new solar, wind, and hydroelectric energy projects.

Underpinning this trend is a recent surge in public support for confronting climate change. Young activists such as the Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg have galvanized that support, and now it is shared by tens of millions of people worldwide, according to a raft of opinion polls ahead of the summit.

A survey of 31 countries commissioned by the BBC – including 18 also polled before the Paris summit six years ago – found an average of 56% of respondents wanted their governments to take a “leading role” in forging an agreement in Glasgow. That was up from 43% before Paris.

The responses in China and India, another major economy resisting calls for a wholesale move away from coal, were striking. In China, only 18% had wanted their leaders to push for progress in Paris. Now, the figure was 46%. In India, it jumped from 38% to 56%.

An even wider survey, under U.N. auspices, polled 1.2 million people across 50 countries. Two-thirds of respondents defined climate change as a “global emergency” and wanted to see greater use of renewable energy sources. Strong support for renewables was found even in carbon-dependent economies like the United States, Australia, and Russia.

And the move to renewables is gathering pace.

A mix of early subsidies and recent economies of scale means that the wind and the sun now generate electricity more cheaply than coal-powered fuel stations. The cost of one technology critical to green power sources – storage batteries – has also been falling.

On the horizon is another potentially game-changing energy source, capable of fueling not just homes, but factories, ships, and possibly even aircraft: emissions-free hydrogen, produced using wind or solar energy.

When it comes to cars and trucks, the shift from carbon is already underway.

Sales of new gas or diesel vehicles will be forbidden in Britain by 2030, and by 2035 in the 27-member European Union. And consumers are voting with their pocketbooks. Last month, for the first time, the top-selling car in both Britain and the EU wasn’t a Ford, a Renault, or a Hyundai.

It was a battery-powered Tesla.

The business world has also begun to shift gears.

On the margins of the summit on Wednesday, a coalition of the world’s leading banks and finance groups – the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero – announced a commitment to support the goal of net-zero carbon emissions in future investment decisions. Assembled by a former head of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, the coalition members control total assets of $130 trillion.

Their announcement amounted to industrywide backing for a groundbreaking decision two years ago by BlackRock, the world’s top investment manager, to make environmental sustainability its “new standard for investing.” It was a move that the New York-based firm described as simply economic common sense. “Climate risk,” it concluded, “is investment risk.”

Climate activists, and leading scientists, still want Glasgow to produce far more over the next two weeks than the “momentum” Mr. Kerry mentioned.

One reason: They’re aware that even with worldwide support for renewables, their development and use will have to be scaled up enormously, and quickly, if they’re going to replace existing carbon-heavy energy sources and slow global warming.

But they also know that – given the current trends, and the green-energy tools and strategies now available – what happens after Glasgow will be critical.

Ms. Thunberg herself seemed to be looking past the summit in a reflective BBC television interview just before it started.

“We must remember there’s not a point where everything is lost. If we can’t keep the global temperature rise to below 1.5,” she said, smiling, “then we’ll do 1.6 … and so on.”

“It’s never too late to do as much as we can.”

The Explainer

Why the Hindu Festival of Lights is spreading around the world

The appeal of this Hindu celebration, our reporter finds, may lie in universal values such as the supremacy of good over evil and spiritual light over darkness.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

The season of Diwali is a time for families and friends to come together in joy. Celebration of this Festival of Lights stretches back 2,500 years across South Asia and is primarily observed by Hindus.

But in recent years, the celebration has swelled in popularity worldwide. Part of the reason Diwali has an ability to span the globe, cultural observers say, is because at its core it offers the universal message of the power of good over evil.

“I think people are drawn to Diwali because they find aspects of it that resonate with things they believe in, whether they’re Hindu or not,” says Shereen Bhalla, director of education, diversity, and inclusion at the Hindu American Foundation in Washington, D.C.

For many, the insecurity caused by the pandemic and the racial reckoning of the past two years has also created a longing for celebrations that uplift heritage and identity. Ms. Bhalla says Diwali provides optimism and comfort during a time when both may seem hard to find.

“People look to Diwali [because] it symbolizes the victory of good over evil, knowledge over ignorance, and spiritual light over darkness,” she says. “Now more than ever, people are drawn to that.”

Why the Hindu Festival of Lights is spreading around the world

Lamps light streets and fireworks illuminate the night sky with beautiful, colorful designs. Playful rangoli designs dance across floors. The smell of home-cooked sweets wafts through rooms of celebration, as families and friends come together in joy.

It’s the season of Diwali, one of the largest religious festivals in the world. Also known as the Festival of Lights, the celebration stretches back 2,500 years across South Asia.

But in recent years, Diwali has swelled in popularity worldwide, and in some cities in the United States, Diwali celebrations attract thousands of participants each year. One of the largest festivals takes place in San Antonio. In 2019, a citywide Diwali celebration drew more than 40,000 people.

Awareness of its cultural importance comes as Indian American culture grows more visible in the U.S. with the election of Vice President Kamala Harris. In recent years, a number of states have formally recognized October as Hindu Heritage Month.

Part of the reason Diwali has an ability to span the globe, cultural observers say, is because at its core it offers the universal message of the power of good over evil.

Where does it come from?

Diwali is primarily observed by Hindus – the majority of whom reside in India. But different faith traditions have their own origin stories for Diwali.

North Indian Hindus celebrate the royal homecoming of Lord Rama following a victorious battle, while South Indian Hindus commemorate Lord Krishna’s defeat of a demon. Jains honor a spiritual leader’s attainment of nirvana, while Buddhists mark the day an emperor from the third century B.C. converted to Buddhism.

What unites the differing interpretations is a celebration of light; Diwali, after all, means “row of lights” in Sanskrit.

Unlike many Western holidays, Diwali isn’t observed on the same date every year, though it always falls between October and November. Following the Hindu lunar calendar, the main day takes place on the darkest day of the month of Kartik (Nov. 4 this year) but celebrations last five days.

How is it celebrated?

At the start of festivities, people flood markets to purchase gold, silver, kitchen utensils, and clothes. Families clean houses and draw rangoli, an Indian art form made with colored powder, on floors to welcome the blessings of Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity.

An array of home-cooked confections are prepared, from a sweet semolina dish called halwa to a fudge-like treat known as barfi. Families and friends visit and exchange gifts, their gatherings encompassed by a backdrop of warm, glowing light.

From oil lamps to LEDs, all lights are lit in celebration. Candles line the entrances to homes; string lights wrap trees and line apartment balconies.

Celebrations take place in community centers, in temples, and on streets; parades and dance performances are held. Outside India, South Asian communities host gatherings in city centers and cultural spaces, welcoming all to join the festivities.

Why is it gaining attention now?

When it comes down to it, Diwali has a lot in common with other global holidays. The gatherings, gift exchanges, and lights of Diwali are reminiscent of celebrations of Christmas, Hanukkah, and Lunar New Year.

“I think people are drawn to Diwali because they find aspects of it that resonate with things they believe in, whether they’re Hindu or not,” says Shereen Bhalla, director of education, diversity, and inclusion at the Hindu American Foundation in Washington, D.C.

And curiosity about the holiday is growing. Recently, Ms. Bhalla has seen more people reaching out to the foundation to request educational materials about Diwali for classrooms. “We’re seeing this huge uptick in people wanting to not just celebrate Diwali, but also make sure they’re doing it appropriately.”

For many, the insecurity caused by the pandemic and the racial reckoning of the past two years has also created a longing for celebrations that uplift heritage and identity. Ms. Bhalla says Diwali provides optimism and comfort during a time when both may seem hard to find.

“People look to Diwali [because] it symbolizes the victory of good over evil, knowledge over ignorance, and spiritual light over darkness. Now more than ever, people are drawn to that.”

Television

It’s bleak, bloody, and No. 1 on Netflix. How ‘Squid Game’ won the pandemic.

Art often overdramatizes reality to underscore a point. In the case of this violent TV show, our reporter finds its popularity based on a common anxiety over debt, a sense of societal unfairness, and the lengths people may go to be free.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Popular show “Squid Game” has conquered 94 countries and counting with its tracksuits and bleak message of social inequality, spawning hundreds of memes in the process and becoming the anti-“Ted Lasso.” Within a month of its mid-September debut, it overtook steamy Regency romance “Bridgerton” as Netflix’s most-watched series ever.

That people gravitate toward dystopian fiction to make sense of difficult times is nothing new – liberals turned George Orwell and Aldous Huxley into bestselling authors, decades after their deaths, during the first months of the Trump presidency.

“Squid Game,” however, has become part of the global conversation in a way that few other stories have. Its rise reflects a growing appetite for Korean culture, the desire for a novel streaming experience, and a sense of economic uncertainty around the world – all while reigniting debates around the role of violence in media.

“Global audiences have been living in an increasingly precarious world, especially since the pandemic began,” says Sung-Ae Lee, an Asian studies lecturer at Australia’s Macquarie University and expert on South Korean film and television. “And it seems that during dark times, people turn to dystopian stories ... because it can be a way of processing trauma.”

It’s bleak, bloody, and No. 1 on Netflix. How ‘Squid Game’ won the pandemic.

It makes “The Hunger Games” look like a third grade field trip. It doesn’t star Jennifer Lawrence or Woody Harrelson or any other big Hollywood names. And it’s got subtitles – poorly written ones at that.

But “Squid Game” has conquered 94 countries and counting with its tracksuits and bleak message of social inequality, inspiring hundreds of memes and becoming the anti-“Ted Lasso.” Within a month of its mid-September debut, it overtook steamy Regency romance “Bridgerton” as Netflix’s most-watched series ever.

That people gravitate toward dystopian fiction to make sense of difficult times is nothing new – liberals turned George Orwell and Aldous Huxley into bestselling authors, decades after their deaths, during the first months of the Trump presidency. “Squid Game,” however, has become part of the global conversation in a way that few other stories have. Its rise reflects a growing appetite for Korean culture, the desire for a novel streaming experience, and a sense of economic uncertainty around the world – all while reigniting debates around the role of violence in media.

“Global audiences have been living in an increasingly precarious world, especially since the pandemic began,” says Sung-Ae Lee, an Asian studies lecturer at Australia’s Macquarie University and expert on South Korean film and television. “And it seems that during dark times, people turn to dystopian stories ... because it can be a way of processing trauma.”

In these contexts, she adds, violence is “used to both engage audiences and encourage them to view society critically.”

Personal struggle strikes a global chord

Part of the popularity of “Squid Game” comes down to a basic rule of internet virality: Hype feeds hype.

“Everything [on social media] was ‘Squid Game’-related. After a certain point in time, I couldn’t relate to the memes anymore,” says Nyah Tewani, a junior at Northeastern University in Boston. “I was like, ‘OK, I have to watch it so that I can actually know what’s going on.’”

Other viewers have praised the show for its cinematography, outstanding cast, genre-bending humor, and unique premise.

“[‘Squid Game’ was] something that I had never seen before,” says Ben Reingold, a visual and media arts student at Emerson College in Boston. “The entire concept of playing kids’ games to be able to keep your life is just completely nuts to me. ... A lot of American films would not go that far.”

This isn’t the first story where those who are “haves” pit “have-nots” against one another in a play-to-the-death competition. But unlike in “The Hunger Games” or Japanese film thriller “Battle Royale,” “Squid Game” participants actually have the opportunity to end the games if the majority votes to leave. This happens after the first trial, a robot-monitored round of “red light, green light” where 255 of the 456 players are gunned down for moving at the wrong time.

When confronted with the real-world challenges of living in debt, almost all return to the deadly games for the chance to win roughly $38 million. This includes a North Korean defector who needs $33,000 to smuggle her mother across the border, and a kindhearted father whose debt and gambling problems are tearing his family apart. The games may be outlandish, but the dystopian world around them is very real.

“The show is motivated by a simple idea,” director Hwang Dong-hyuk recently told The Guardian. “We are fighting for our lives in very unequal circumstances.”

The 2007-08 global financial crisis hit South Korea hard. Like many other Koreans, Mr. Hwang had to take out personal loans when he was unable to work. During this low point, he wrote “Squid Game,” and though it took a decade for a studio to pick up the series, its anti-capitalism messages are even more relevant today.

South Korea’s household debt-to-GDP ratio is now the highest in Asia, contributing to a growing wealth gap. Around the world, similar trends have been exacerbated by the pandemic, reports the International Monetary Fund, with 120 million people pushed into extreme poverty as billionaires became wealthier.

Jacob Atagi, in Alexandria, Virginia, watched “Squid Game” after seeing clips of the show on TikTok, and recognized the anxieties around debt and financial security. He saw them play out among his friends who graduated in 2020, during the start of the pandemic; some had job offers pulled at the last minute, and others had to wait months to start work. “So you definitely see how [“Squid Game”] would play into those fears,” says the associate at KPMG, adding that he’s recommended the show to several friends.

New York University student Morgan Martin binge-watched the series within a few days. She says the main character, Seong Gi-Hun (played by Lee Jung-jae), reminded her of her own financial worries when starting college. “Though his debt was definitely different than mine, [I related to] that feeling of trying to do whatever you can to make money,” she says.

The extreme inequality showcased in “Squid Game” was also familiar to Ms. Tewani, the Northeastern student, who grew up in Johannesburg until she was 16. “That part resonated with me, because I [realized] I’ve been put in a position where I’m so privileged that I would never feel inclined to do those things,” she says. “It’s so easy to say, ‘Oh yeah, I would never [choose to compete].’ But a lot of people would actually go for that because it’s their livelihood and they’re trying to support their families.”

Violence: gratuitous or necessary?

“Squid Game” is all over social media, though it’s not always clear how gruesome it is from a screenshot of the pastel- and primary-colored sets. The show is rated TV-MA for graphic violence and mature themes. Regardless of viewers’ tolerance for gore, Ms. Tewani believes understanding the gravity of the players’ circumstances outside the arena is key.

“People went into this game because they’re suffering from severe economic problems,” she says. “You can’t romanticize that.”

By showing each death head-on, she says, “Squid Game” forces viewers to confront the fact that this is not a normal game show. People aren’t being “eliminated,” but killed. “I think that if they censored it even slightly, it wouldn’t have gained the same traction,” she says.

But that doesn’t mean all 142 million viewers actually enjoyed “Squid Game.”

“It’s interesting to watch, but it doesn’t make you feel good,” says Amy Lu, associate professor at Northeastern University and director of the school’s Health Technology Lab. The show’s graphic nature – especially the mass death witnessed during the first game – strikes her as a marketing strategy.

“I think it’s a very successful commercial operation in terms of predicting people’s attention,” she says. “People’s sensation-seeking curve, especially for guys, will grow during their adolescent years and then gradually go down.”

Combine that with the simplicity of the games, versions of which are played by children in many cultures, and she says it’s easy to see why the show took off.

Dr. Lee in Australia has a different take on the role of violence in “Squid Game.”

“Audiences are not necessarily drawn to violence in itself,” she says, “but it heightens tension and suspense, and an audience’s visceral response to violent images ... becomes a metaphor for deep social malaise.”

Mr. Hwang is one of her favorite directors, and before “Squid Game,” he was best known for films like “Silenced” (2011). The movie dealt with real-life abuse of students at Gwangju Inhwa School for deaf people. Mr. Hwang depicted not only the abuse, but also the structural issues that allowed teachers and administrators to act with impunity. More than 4 million Koreans saw the movie, and the ensuing public outrage pushed the National Assembly to abolish the statute of limitations for sex crimes against minors and disabled people.

“That’s really powerful,” says Dr. Lee. “These kinds of things can change society.”

Staff writers Pavithra Rajesh and Tomás González contributed to this report.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

No time for anger over climate change

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

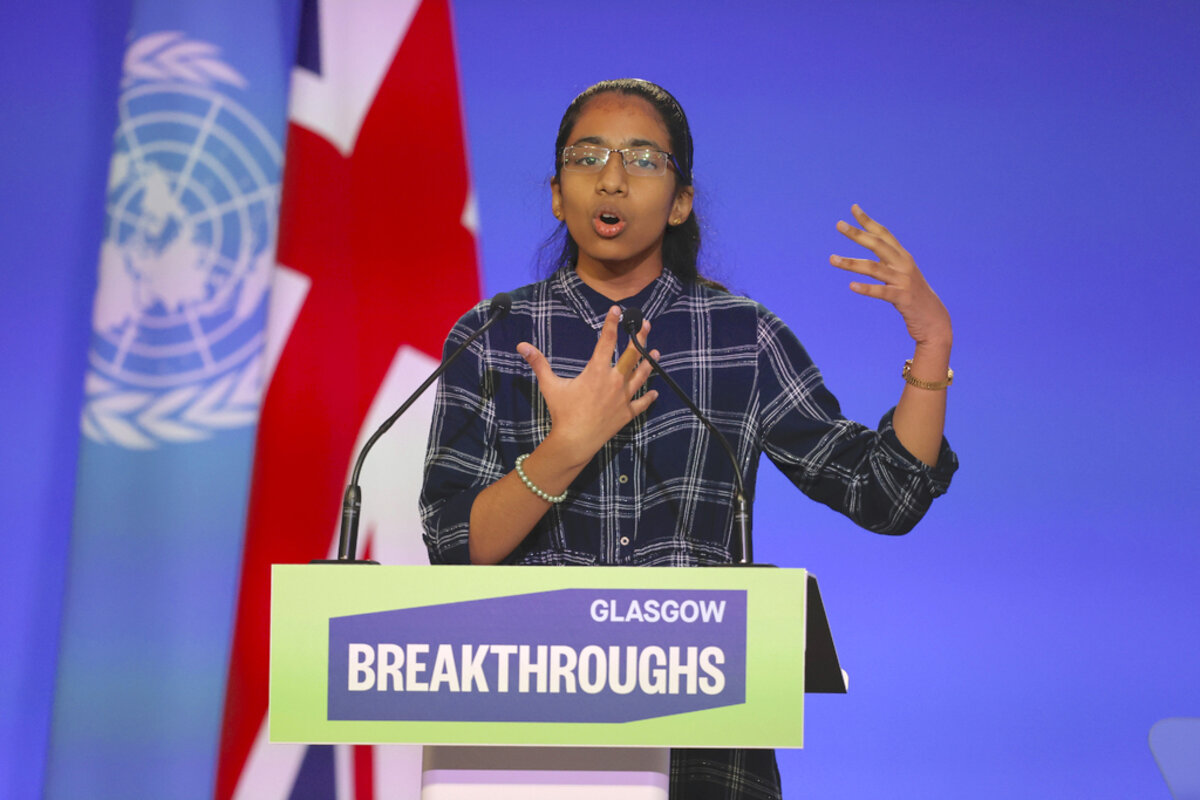

Of all the speakers so far at the climate summit in Scotland, one has drawn an enthusiastic standing ovation. It was 15-year-old Vinisha Umashankar who told the crowd: “I’ve no time for anger. I want to act. I’m not just a girl from India. ... I’m a student, innovator, environmentalist, and entrepreneur, but most importantly, an optimist.”

She was invited to speak because she was a finalist in a global contest aimed at turning back doomism about climate change by finding individuals who have invented the best market-ready solutions to repair the planet. Vinisha’s invention was a solar-powered iron that could be used by the 10 million street vendors in India who now steam-press people’s clothes with irons heated by air-polluting charcoal.

Vinisha says that all of the winners and finalists for the prize “chose not to complain” about climate change. Rather the contestants’ inventions show “the greatest challenge in the history of our Earth is also the greatest opportunity.”

The audience clapping for her speech probably admired her certainty about finding fresh solutions for a difficult challenge. “You are never too young to make a difference,” she said. Nor too old or cynical to keep on trying.

No time for anger over climate change

Of all the speakers so far at this month’s climate summit in Scotland, one has drawn an enthusiastic standing ovation. It was 15-year-old Vinisha Umashankar who told the crowd:

“I’ve no time for anger. I want to act. I’m not just a girl from India. ... I’m a student, innovator, environmentalist, and entrepreneur but most importantly, an optimist.”

She was invited to speak because she was a finalist in a global contest aimed at turning back doomism about climate change by finding individuals who have invented the best market-ready solutions to repair the planet.

Vinisha’s invention was a solar-powered iron that could be used by the 10 million street vendors in India who now steam-press people’s clothes with irons heated by air-polluting charcoal. She was 14 when she came up with the idea. She was also the youngest contestant for the first Earthshot Prize and one of the 15 finalists.

Vinisha says that all of the winners and finalists for the prize “chose not to complain” about climate change. Rather the contestants’ inventions show “the greatest challenge in the history of our Earth is also the greatest opportunity. We lead the greatest wave of innovation humanity has ever known.”

The Earthshot Prize, named after President Kennedy’s “Moonshot” space program of the 1960s, was set up last year by Prince William, the Duke of Cambridge and second in line to the British throne. The contest drew 750 nominations from 86 countries. The first five prizes, announced last month, came with a $1.37 million award and access to participating companies eager to invest in new eco-solutions.

The future king says the prize’s purpose is to highlight ingenuity around environmental problems in order to prevent “a real risk that people would switch off, that they would feel so despondent, so fearful and so powerless.” In the spirit of including everyone in dealing with climate change, he wants to show that anyone has the potential to discover solutions.

This fits with a new study by researchers at Rand Corp. that looked at the results of another innovation-spurring prize. Between 1996 and 2019, the Lemelson Foundation and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology awarded an annual $500,000 prize to 26 young inventors. Their innovations led to the startup of more than 140 companies.

The economist who led the study, Benjamin Miller, drew this conclusion: “If you want to maximize the benefits to society, you need everybody to have a chance to be the best inventor they can be. There’s a whole pool of people we’re missing out on because they’re not being engaged.”

Or as Paul Romer, winner of the 2018 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, once wrote: “Every generation has underestimated the potential for finding new ... ideas.”

The audience clapping for Vinisha’s speech probably admired her certainty about finding fresh solutions for a difficult challenge. “You are never too young to make a difference,” she said. Nor too old or cynical to keep on trying.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Love: Our release from alienation

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Susan Stark

Sometimes sadness or anger over a disagreement may make us want to withdraw from an organization or friendship. But yielding to God’s powerful love instead of to the pull of resentment paves the way to reconciliation and healing.

Love: Our release from alienation

Not many things are as sweet as a restored friendship or an estrangement that’s been healed.

Alienation can feel pretty justified when we think that we have been wronged. However, Christ Jesus urged us to love God, divine Love, so deeply and purely that we naturally express love to everyone around us. Alienation has no place in our hearts because it has no place in God.

In spiritual fact, we are not personalities that have to fill up on love before we can share it. God holds each of us in infinite affection as Love’s own spiritual likeness. We are God’s reflection, lovable and loving, fully able to express all-embracing Love, God.

We can come to know that, and feel Love’s warm embrace of us as we love even our so-called enemies, doing “good to them that hate you,” as Jesus said. He also explained why such loving is natural to us: “That ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust” (Matthew 5:44, 45).

The loving Father that Jesus knew so well couldn’t be anything other than impartially just. But this justice is different from the judgments we make about who’s right and who’s wrong in a disagreement. God’s justice is divine perfection that denies evil any power.

Following these teachings of Jesus doesn’t excuse bad behavior or relieve someone else of needed reform, but it transforms what we are responsible for – our thinking. Changing our view of others to what God knows about them heals mental anguish along with any desire to punish someone for our pain.

Christian Science further explains that it’s mortal perceptions that create “enemies.” Mary Baker Eddy, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, gave to these thoughts the name “mortal mind.” Mortal mind can’t cognize the “male and female” that God created, so it gets stuck in conflicts and misunderstandings – which push us into alienation. Because mortal mind isn’t real Mind, God, we can reject the stirred-up emotions it offers.

Mrs. Eddy wrote: “Can you see an enemy, except you first formulate this enemy and then look upon the object of your own conception? What is it that harms you? Can height, or depth, or any other creature separate you from the Love that is omnipresent good, – that blesses infinitely one and all?” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 8).

It’s not a personal love that repairs strained relationships; it’s unselfed love, straight from God. A pure affection doesn’t hold grudges. Honesty with ourselves slows down a rush to make snap judgments about someone. These graces of spiritual love make human pride, deception, and hate less potent and real to us. Praying for our enemies and ourselves rights the wrongs we suffer by shifting our human perspective to the divine understanding of everyone’s true identity as Love’s infinite expression. The effect of this can be tremendous.

At one time, I blamed someone in my church for decisions I disapproved of. I walked away from any association with this individual for many years. But during those years, my love for God and church – along with its members – was growing.

Finally, I said to myself, “I can love enough to work with people I may disagree with.” As I became more active in church work, I couldn’t avoid contact with this person. One week, I had a few emails to write to my one-time enemy, and I wrote them with as much love as I could. As if out of the blue, what was shared in a response to one of my emails was the spiritual truth I needed to lift my distress about some work problems. This person gave to me freely. I wrote back in appreciation and sincere friendship. And this friendship continues.

We often see ourselves as totally right and someone else as totally wrong. This is just the opposite of what’s provable in Christian Science. God, good, is right. Wrongs are corrected as our own thinking comes into line with Love, divine Principle. The good we practice consistently is what links humanity with the harmony of Love.

We cannot be kept from yielding to the great power and warmth of Love. God is right with us and gives us integrity, honesty, and compassion. All are part of an unselfed love that lets the infinite Love that is God reconcile our relationships and free us from alienation.

Adapted from an editorial published in the September 2021 issue of The Christian Science Journal.

A message of love

Madame Mayor

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about the latest Marvel superhero movie, which has something the franchise hasn’t had before: an Academy Award-winning female director.