- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- For Biden presidency, Ukraine crisis offers a defining moment

- Minority report: How justices from Harlan to Breyer shaped legal opinion

- Long neglected, Afghan villagers look to outside world for aid

- For Black LGBTQ Christians, storytelling is a tool of resilience

- On Broadway: This musician is in the pits, but far from blue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Taking the long view of today’s news

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

The pull of the moment can be strong. In a time of 24-hour cable news and social media, it can be dizzying. But today’s issue of the Monitor Daily takes a different approach: the long view.

As Russian troops gather on the Ukrainian border, Howard LaFranchi notes that the crisis has perhaps just answered a debate that has lingered since the fall of the Soviet Union: Why are NATO’s transatlantic ties relevant today? The long view could see a renewal of that flagging purpose.

As United States Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer steps down, his replacement will join the court in the legal minority. Is that a recipe for frustration? Henry Gass looks at how conservative justices such as Clarence Thomas faced the same situation, waiting decades to come to prominence. The long view is that the years in the minority are not wasted.

In Afghanistan, the recent rise of the Taliban is simply part of a 40-year cycle of political instability. But through every twist, one thing has remained the same: the rural areas at the heart of Afghanistan that have been ignored or used as pawns. Franz J. Marty offers a portrait of this unchanging Afghanistan – a key perspective to any long-view solution.

We also look at how, after decades of being marginalized, queer Black people of faith are finding strength and support in one another, and how a musician finds joy amid 35 years of ups and downs on Broadway.

News demands being of the moment. But adding a longer view often helps uncover what that moment means.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

For Biden presidency, Ukraine crisis offers a defining moment

President Joe Biden has been preaching the importance of democracies standing up to autocrats worldwide. In Ukraine, Russia might make his point for him.

Vladimir Putin’s mobilization of more than 125,000 troops around Ukraine has accomplished something he almost certainly did not intend. It has reinvigorated President Joe Biden’s Atlanticist roots, and has revived a transatlantic alliance that in recent years had revealed fissures and a faltering unity of purpose.

Moreover, the Russian leader’s efforts to smother Ukraine’s fledgling, pro-Western democracy have helped put meat on the bones of President Biden’s ringing but as-yet squishy call to defend the world’s democracies.

“This is a defining moment for President Biden and the Biden administration foreign policy,” says Andrea Kendall-Taylor, director of the Transatlantic Security Program at the Center for a New American Security in Washington. “If an aggressive power can succeed in changing borders through military action, that poses dangerous risks to the entire international system.”

Beyond that, “This fits into his understanding of the world right now as an arena where liberal democracy is confronting the rising revisionist and authoritarian regimes,” she says. “And in his view, it’s time to demonstrate that the U.S. is willing to stand up against those authoritarian actors who are testing us.”

For Biden presidency, Ukraine crisis offers a defining moment

As Russia’s Vladimir Putin has amassed more than 125,000 troops on Ukraine’s borders, a mobilization that threatens the largest military operation in Europe since World War II, he has accomplished something he almost certainly did not intend.

President Putin has reinvigorated President Joe Biden’s Atlanticist roots. And he is breathing new life into a transatlantic alliance that in recent years has revealed fissures and a faltering unity of purpose – between Europe’s East and West, and between a Europe less focused on security issues and an America anxious to turn eastward toward Asia and an assertive China.

Moreover, the Russian leader’s efforts to smother Ukraine’s fledgling, pro-Western democracy have helped put meat on the bones of President Biden’s ringing but as-yet squishy call to defend the world’s democracies.

Indeed, some foreign policy analysts say Mr. Putin’s Ukraine gambit – and his efforts to undermine the democratic principles undergirding the transatlantic partnership – has provided a salient point of reference for Mr. Biden, who has depicted liberal democracy’s ability to stand up to rising autocracies as key to this century’s defining ideological battle.

“This is a defining moment for President Biden and the Biden administration foreign policy,” says Andrea Kendall-Taylor, director of the Transatlantic Security Program at the Center for a New American Security in Washington.

“This administration came in amid questions around the importance and centrality of the NATO alliance to U.S. security, and over the last year there were a lot of strains – in the wake of the drawdown in Afghanistan and the way it was handled, and over the [U.S.-Australia] submarine deal – that led to questioning of the strength of relations with European allies,” she says.

“But Russia’s actions have reminded everyone of the importance of transatlantic unity and got everyone singing from the same sheet of music,” adds Ms. Kendall-Taylor, a former senior intelligence officer for Russia and Eurasia in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

“Yes, this is about helping the Ukrainians help themselves,” she says, “but there is also a widespread understanding that if we don’t respond significantly to this crisis, you run the risk that President Putin will feel emboldened to test the alliance in even more threatening ways.”

The United States delivered to Moscow Wednesday what Secretary of State Antony Blinken described as a “diplomatic path forward” for resolving the Ukraine crisis. The written response to Russia’s demands concerning the West’s posture in Eastern Europe accompanied a similar written reply from NATO.

Russia has demanded that NATO agree never to accept Ukraine as a member and that NATO forces and U.S. nuclear arms be pulled from Eastern Europe in exchange for a pullback of Russian forces from Ukraine’s borders. Both the U.S. and NATO have called such demands “nonstarters,” but officials said the letters offered other proposals for mutual European security enhancement.

In a press briefing Wednesday, Mr. Blinken put the responses delivered to Russia in the context of the values he said have guided the alliance since its founding.

“We make clear that there are core principles that we are committed to uphold and defend, including Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, and the right of states to choose their own security arrangements and alliances,” he said.

Test of U.S.-Europe unity

Over recent weeks as the Ukraine crisis has intensified, questions have arisen over the strength and durability of U.S.-Europe unity toward Russia.

Doubts have surfaced over how far some European countries would go in imposing what Mr. Biden says will be “severe sanctions” and “overwhelming economic costs” if Russia invades Ukraine. Some Europe analysts have suggested that economic powerhouse Germany could end up the weak link in transatlantic unity – suggestions that were only reinforced by recent reports that Germany is disrupting the delivery of arms to Ukraine, and that Britain is having flights delivering anti-tank weaponry to Ukraine take detours around Germany.

As if to answer those doubts, Mr. Blinken underscored that the response to Moscow was the result of close consultation with European allies. “There’s no daylight among the United States and our allies and partners on these matters,” he said.

The accuracy of that statement is likely to be tested over the coming weeks and may depend on how the Ukraine crisis develops. But what seems less debatable is the significant impact the confrontation with Russia over Ukraine is having on President Biden’s foreign policy.

Presidents know that the foreign policy decisions they make can determine the course of their presidencies.

Barack Obama, for example, issued a red line to Syria’s Bashar al-Assad about the use of chemical weapons and threatened to unleash the weight of the U.S. military against him in Syria’s civil war. But in the end, Mr. Obama chose not to entangle the U.S. in another Middle East war or to be distracted from the top priority of confronting China and fortifying partnerships in Asia.

Mr. Biden came into office declaring China and its authoritarian system of government the era’s most important geopolitical challenge. At the same time, growing doubts about the relevance and durability of the 75-year-old transatlantic alliance met him as he entered the White House.

But Biden aides and foreign policy analysts say Russia’s Ukraine campaign has caused a rethinking of who and what constitute the most important short- and long-term national security challenges to the U.S. – and a new appreciation for the importance of America’s Western and liberal democratic allies in confronting those challenges.

“Biden and the team around him are dyed-in-the-wool Atlanticists, and I think we see the president reaching down into those roots as he has responded to Russia’s aggressive actions towards Ukraine,” says Charles Kupchan, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations who served as senior director for European affairs in the Obama National Security Council.

Mr. Biden’s announcement that he’d send 8,500 troops to NATO’s eastern flank – and potentially 10 times that many – in the event of a fresh Russian incursion into Ukraine is meant to be a strong deterrent to Mr. Putin, Mr. Kupchan says. But he adds that at least as important to Mr. Biden as Ukraine’s sovereignty is the wider threat that the Russian leader’s actions pose to America’s European allies and the principles of democratic governance more broadly.

“I see transatlantic relations as rock solid, and in some ways the connection to Europe has been reinforced in this administration by the crisis in liberal democracy and Putin’s aggressive efforts to undermine it,” he says. “On both sides of the Atlantic, this is not just about resisting the Russian aggression; it’s about locking down who, together, we are.”

China still a priority

As Mr. Biden reassesses his foreign policy priorities, China will almost certainly retain its status as America’s top long-term challenge, a range of observers say, even if Russia ends up diverting attention from the administration’s focus on the Indo-Pacific region.

“Would a Russian invasion of Ukraine distract the U.S. from a focus on China and the Asia-Pacific? Sure,” says Mr. Kupchan. “The main distraction would be to the political capital and the political time it would take up, more than the resources addressing [Russia’s aggression] would require.”

Ms. Kendall-Taylor notes that both the National Security Strategy and the National Defense Strategy, documents the administration is expected to unveil in the coming weeks, will almost certainly reflect a reassessment of the threats Russia poses in light of the Ukraine crisis.

“The priority for everyone is still China, but I think we’ll see changes in those forthcoming documents because this is a game changer,” she says. “If an aggressive power can succeed in changing borders through military action, that poses dangerous risks to the entire international system.”

Beyond that, she says the Ukraine crisis is prompting a “realignment” of foreign policy priorities because it illustrates the dangers to democratic governance that Mr. Biden has been talking about since taking office.

“This fits into his understanding of the world right now as an arena where liberal democracy is confronting the rising revisionist and authoritarian regimes,” she says. “And in his view, it’s time to demonstrate that the U.S. is willing to stand up against those authoritarian actors who are testing us and pushing ahead in ways that would hurt the U.S. in the long term.”

Minority report: How justices from Harlan to Breyer shaped legal opinion

With Justice Stephen Breyer retiring, can his replacement have a significant impact despite being in the liberal minority? History shows a Supreme Court justice can always leave a mark.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

President Joe Biden reiterated his pledge today to nominate a Black woman to replace Justice Stephen Breyer, and while this nominee won’t change the court’s ideological balance – and will likely be in its minority for some time – she will still have a significant influence on the United States in a variety of ways. It just may take some time for that influence to be felt.

There’s a long history of justices in the minority entrenching their positions as a “committee of one,” says Barbara Perry, director of presidential studies at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center. Chief Justice William Rehnquist, for a time, was nicknamed the Lone Ranger, propping up a small cowboy doll in his chambers. The Supreme Court always plays the long game, she adds. “It is not lost forever to the liberals.”

The quintessential example is Justice John Marshall Harlan’s solo dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 case in which the Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation was constitutional so long as facilities were “separate but equal.” Sixty years later, in Brown v. Board of Education, Harlan’s dissent provided the legal foundation for the court to unanimously overturn Plessy.

Minority report: How justices from Harlan to Breyer shaped legal opinion

With Justice Stephen Breyer announcing his retirement Thursday, his replacement will follow in the footsteps of every justice before them by taking their place on the lowest rung of the highest court in the land.

This new justice – early favorites include federal appellate Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, U.S. District Judge J. Michelle Childs, and California Supreme Court Justice Leondra Kruger – will join a court where they will have even less influence than most, at least when it comes to shaping the law.

The Supreme Court has had a conservative lean for almost 50 years, but it’s now perhaps the most conservative it’s been since the 1930s. Six Republican-appointed justices sit on the court, and three of them are in their 50s. Not only does the court seem poised to roll back key liberal precedents on abortion and affirmative action, but those conservative justices will likely shape the law for decades to come.

President Joe Biden reiterated his pledge today to nominate a Black woman to replace Justice Breyer, and while this nominee won’t change the court’s ideological balance – and will likely be in its minority for some time – she will still have a significant influence on the country in a variety of ways. It just may take some time for that influence to be felt.

“Having a Democratic nominee replace Justice Breyer is not going to change anything that we are immediately looking at. But the politics of the judiciary change over time,” says Lori Ringhand, a professor at the University of Georgia School of Law.

“Even within what appears to be a solid block, you can see shifts over time,” she adds. “It would not surprise me if [in] what looks right now like a kind of ideological, lockstep conservative block of justices, we’re going to start to see where they differ among themselves.”

The court’s “lone rangers”

It takes about five years to learn the job, justices often say.

Seniority dictates much at the high court, so the newest justices typically have few responsibilities and little influence. The most senior justices decide who writes opinions, and the newest justice is typically assigned a few, often unanimous and uncontroversial, cases. Their colleagues need time to get a feel for their views on different areas of the law, and – unless they’re Justice Neil Gorsuch on his first day – they are rarely vocal questioners during oral arguments.

There’s a long history of justices in the minority entrenching their positions as a “committee of one,” says Barbara Perry, director of presidential studies at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center. Chief Justice William Rehnquist, for a time, was nicknamed the Lone Ranger, propping up a small cowboy doll in his chambers. The Supreme Court always plays the long game, she adds. “It is not lost forever to the liberals.”

The quintessential example is Justice John Marshall Harlan’s solo dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 case in which the Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation was constitutional so long as facilities were “separate but equal.” Sixty years later, in Brown v. Board of Education, Harlan’s dissent provided the legal foundation for the court to unanimously overturn Plessy.

An earlier solo dissent resonated deeply with writer and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. In a letter to Harlan about the Civil Rights Cases of 1883, Douglass wrote that his dissent “should be scattered like the leaves of Autumn over the whole country.” “I have nothing bitter to say of your Brothers on the Supreme [Court], though I am amazed and distressed by what they have done,” he added. “I wish to assure you if you are alone on the bench, you are not alone in the country.”

Other justices have had similar long-term influence on the law through their separate opinions, including conservative justices. Justice Antonin Scalia spent his early years on the court writing separately to expound the virtues of originalism and textualism. Today, those approaches to constitutional and statutory interpretation dominate both the high court and the judiciary as a whole.

Justice Clarence Thomas, now the court’s most senior member, has also seen that kind of labor bear fruit. After years of solo opinions arguing that, for example, political donors should be able to give anonymously and that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to bear arms, those opinions have now become the law of the land.

Justice Breyer could have a similar long-term impact on the law – as could his replacement.

“Breyer famously brought a practical, pragmatic approach to his jurisprudence that undoubtedly helped shape the direction of the court,” says Steven Schwinn, a professor at the University of Illinois, Chicago, School of Law.

“A new justice is going to have to find their own place.”

How Breyer negotiated his role

Justice Breyer, for example, has argued for years – to no avail – that the death penalty is unconstitutional. It’s not unthinkable that decades from now, his dissents form the basis for the Supreme Court outlawing capital punishment.

But he’s also exemplified another way a justice can shape the law from a minority position: negotiating and working with his colleagues on the bench.

In the 2012 case in which the Supreme Court voted to uphold the Affordable Care Act for the first time, Justice Breyer was reportedly pivotal in crafting a compromise with Chief Justice John Roberts that upheld the act’s individual mandate but struck down its Medicaid expansion provision. He reportedly played a similar role, this time with Justice Anthony Kennedy, in brokering a compromise around an affirmative action case a year later.

Justice Elena Kagan appears to also favor that “bridge-builder” approach, but her colleague in the court’s liberal wing, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, favors what is sometimes called the “bomb-throwing” approach: writing fiery dissents aimed at shaming colleagues and laying out arguments for perhaps overturning the majority in the future.

What approach Justice Breyer’s replacement takes will not be clear for several years. But given that she will be the first Black woman to serve on the high court, she is likely to have a different and more immediate influence on the country.

“Just by virtue of her presence, she will encourage others to be more ambitious in their lives,” says Neal Devins, a professor at the William & Mary Law School.

She will also become the second Black member of the court, joining Justice Thomas, one of the bastions of the conservative supermajority. This could lead to interesting exchanges, says Melissa Murray, a professor at New York University School of Law.

“Right now the person on the court who often sort of presents the African American experience is [Justice] Thomas, and he presents it a particular way,” she adds.

“It runs the risk of presenting the Black experience as monolithic, [that] Clarence Thomas’ experience is the Black experience for all Americans,” she continues. “It would be useful ... to have a Black woman providing her own view of how these issues will hit.”

The nomination could also be especially timely after the court decided this week to hear a case challenging the affirmative action admission policies at two universities. With the case likely to be argued next term, the new justice will be in place to take part.

“When Justice Thomas makes the point that affirmative action, in his view, harms racial minorities,” says Professor Murray, “it will be really important and interesting to watch a Black woman go toe to toe with him and present perhaps an alternative perspective.”

Long neglected, Afghan villagers look to outside world for aid

The Taliban drew their strength from rural areas. Now they’re ignoring them just as the Western-backed government did before. It’s a chronic problem that defies easy solutions.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Franz J. Marty Correspondent

Regimes have come and gone in Afghanistan for decades, but in remote reaches of the country there has been one constant: neglect.

Despite the tens of billions of dollars spent in Afghanistan during two decades of Western intervention, countless remote villages have seen little or no development aid or public services. Villagers had little incentive to support the Western-backed government in Kabul when the Taliban pushed their advance last year.

But the Taliban have done no better, either during their first spell in office, or in the six months since they seized power again.

“During my whole life, no government ever came to help us,” says Salahuddin, a tribal elder in Galai, a remote village in southeastern Afghanistan, whose wrinkled face behind a fuzzy brown beard tells of a life of hardship.

Some of his fellow villagers dare to hope that an end to the war will finally allow aid to reach far-flung places like their hamlet.

Yet with ever more people in Afghanistan requiring assistance, and the country suffering a lack of resources, it seems more likely that Galai, once again, will have to wait.

Long neglected, Afghan villagers look to outside world for aid

Regimes have come and gone in Afghanistan for decades, but in remote reaches of the country there has been one constant: neglect.

For years, the Taliban took advantage of the U.S.-backed government’s failure to provide services to distant villages, using them as staging posts to pave the way for their military victory last August.

But as the Taliban near six months in power, they too have yet to bring aid or development to remote villages like Galai in Gyan district in Afghanistan’s southeastern Paktika province – a frontier region where thick forests cover the hills and where the militants have effectively been ruling for at least a decade.

“During my whole life, no government ever came to help us,” says Salahuddin, a tribal elder from another remote village in Gyan, whose wrinkled face behind a fuzzy brown beard tells of a life of hardship.

In a simple home decorated with Taliban flags and posters in Gyan, the main village of the district with the same name, where local men have gathered to meet a visiting reporter, Salahuddin gesticulates as he recounts the many problems his people have faced.

His perspective is far from unique. Despite the tens of billions of dollars spent in Afghanistan during two decades of Western intervention, countless remote villages have seen little or no development aid or public services.

Such places were left to fend for themselves, and their inhabitants had little incentive to support the Western-backed republic led by President Ashraf Ghani when the Taliban pushed their advance in late spring and summer 2021.

Ignoring the “dusty districts”

“In the beginning, it was a conceptual mistake”, says Thomas Ruttig, a co-founder of the Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) who has worked on Afghanistan, including for the United Nations, since 1988. “The U.S. military did not consider ‘the dusty districts’ in Afghanistan’s hinterlands strategically important, although that was where parts of the Taliban survived.”

And while the United States afterward pursued a variety of strategies in Afghanistan, the U.S. military is now gone; for the first time in 20 years, there is no official U.S. presence whatsoever in the Hindu Kush.

This has had a severe impact on international aid programs, in which the U.S. has played a lead role over the past two decades. Most of them were at least temporarily suspended following the U.S. withdrawal at the end of August.

Yet people in Gyan, as elsewhere across Afghanistan, still put their main hopes in the United Nations and international aid organizations, rather than their own government. The notion that a regime in Kabul should fund and provide services to its citizens seems not to occur to many Afghans, especially in remote parts of the country.

Gyan residents’ trust in, and expectations of, foreign governments are similarly low.

When, after the 9/11 attacks, American troops first passed through the region in their mission to hunt down the remnants of Al Qaeda and their Taliban hosts, nation building was not yet on their agenda.

“U.S. soldiers came to our village only twice or three times shortly after they arrived in Afghanistan. But they only searched houses and, finding nothing, left again. They did not bring any aid,” recalls one man huddled with others last November around a fire in Galai, a hamlet hidden in the vast forest that covers parts of Gyan and neighboring districts.

“The [U.S.-backed] government never came here,” says another. Taliban rule did not change much, either, he adds. “During the past years, the Taliban passed through Galai every now and then, but they did not ask whether we needed anything, and they never provided public services,” he recalls.

Do it yourself

So the people of Galai, and countless similar villages around Afghanistan, had to fend for themselves, even when it came to building basic infrastructure.

“We villagers built the road ourselves about 12 years ago,” says Ali Muhammad, a Galai elder wearing the large yellow turban favored by some tribes in Paktika. The “road” is a poor dirt track that is the only drivable route to the outside world from Galai – as long as there is no heavy rainfall or snow, when it becomes impassable for vehicles.

The lack of roads is not the only problem. In Uchkai, a village at the edge of the forest in Gyan, for example, head teacher Sarif Khan and nine colleagues give lessons to 227 pupils outdoors.

“There is no school building, and there hasn’t been one for the past 17 years,” says Mr. Khan. There is also a shortage of textbooks, and as many as five students must sometimes circle around a single worn-out book.

Such problems have persisted in remote areas like these for decades, as the government in Kabul shifted from a monarchy to a republic, to Soviet-backed communists and then to the mujahideen, before the Taliban first ruled.

For residents of such distant villages, the pattern of hardship and neglect persisted during the 20 years of the Western-backed second Republic, and now under the Taliban’s second Islamic Emirate.

“Protracted needs in hard-to-reach areas of Afghanistan have been documented for a long time,” says John Morse, director of the Danish Committee for Aid to Afghan Refugees, which has been conducting projects in rural areas across Afghanistan since 1984.

“Although some NGOs still made efforts to reach remote villages, it became more and more a security problem to access such areas outside of government control,” adds Mr. Ruttig, the AAN analyst. “The decision of donor countries to focus more on rural areas and agriculture was only made … in 2010. And by then it was probably already too late.”

Mr. Morse, who has worked in Afghanistan in various positions for almost 20 years, says nongovernmental organizations expanded their operations in remote areas of Afghanistan over the past few years, but that “this should have happened years earlier.” Among the challenges the NGOs faced, he says, were security threats and sometimes mixed messages from the Taliban.

Sometimes, agencies focused aid on more populated urban areas so as to make mass distribution more efficient. At the same time, according to a Western employee of a Kabul-based NGO, donor nations’ desire to minimize the exodus of refugees heading to Europe meant they at times obliged NGOs to launch projects in places where large numbers of those refugees came from, rather than where needs were greatest.

“Help us, out of humanity”

While the Taliban during their insurgency did not themselves provide any aid to the neglected hinterlands, their call for jihad against a corrupt and “infidel” government in Kabul resonated more convincingly with many of the often deeply religious Afghan villagers than did Western narratives of democracy and progress, of which they had seen little or nothing at all.

With the Taliban again in charge in Afghanistan, some in remote places like Galai dare to hope that the nationwide reduction in violence will finally allow aid to reach far-flung places like their hamlet.

Yet with ever more people in Afghanistan requiring assistance, and the country suffering a lack of resources, this appears unlikely.

Many Afghans blame this on the U.S. and the international community, disregarding the fact that it has been the Taliban’s actions – in particular their violent takeover of Afghanistan – that have caused most of the current economic crisis that threatens a famine.

“The foreigners have to officially recognize the [Taliban] Emirate and help us, out of humanity,” says Niaz Muhammad, an elder from Galai who uses a crutch to walk. “This is our right.”

This article has been amended to clarify that the reporter met local residents in Galai in a private home.

A deeper look

For Black LGBTQ Christians, storytelling is a tool of resilience

In sharing their stories, Black LGBTQ people are deepening their sense of spirituality and seeking ways to reconnect with church.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

It’s not easy being out in the Black church. None of the seven religious denominations that historically make up the Black church are queer-affirming, but LGBTQ people still exist in these spaces, often quietly. Their experiences challenge the long-held notion that Christian and LGBTQ communities are inherently and irreconcilably at odds.

Today, this deeply ingrained narrative makes it difficult for Black congregations – even those whose members largely support LGBTQ equality – to recognize these congregants in their midst.

By sharing their stories, a growing number of Black, queer Christians are fighting for recognition of their own spirituality, as well as creating new opportunities for community building and individual catharsis.

Don Abram founded the Chicago-based Pride in the Pews project, one organization striving to bring together LGBTQ people of faith. “There are a lot of folks I’ve been in conversation with who have expressed relief, have expressed feeling revived by the opportunity to share their story,” he says.

For Black LGBTQ Christians, storytelling is a tool of resilience

Terria Crank had grown tired. She was tired of hiding her sexuality, of running around with fake boyfriends and keeping secrets from her mom. She was attending church three times a week but wondered if God could even see her. So, at 19 years old, she left the faith.

Years later, her girlfriend – now fiancée – led her back.

“It was honestly Kam who reminded me of God’s love,” she says. “She stopped me from fully walking away. She reminded me that it’s about relationships and not about rules.”

It’s not easy being out in the Black church. None of the seven religious denominations that historically make up the Black church are queer-affirming, but LGBTQ people still exist in these spaces, often quietly. Their experiences challenge the long-held notion that Christian and LGBTQ communities are inherently and irreconcilably at odds. Today, this deeply ingrained narrative makes it difficult for Black congregations – even those whose members largely support LGBTQ equality – to recognize these congregants in their midst.

By sharing their stories, a growing number of Black, queer Christians are fighting for recognition of their own spirituality, as well as creating new opportunities for community building and individual catharsis.

“In some ways, the opposite of resilience is fatigue,” says Don Abram, founder of the Chicago-based Pride in the Pews project, one organization striving to bring LGBTQ people of faith together. “And there are a lot of folks I’ve been in conversation with who have expressed relief, have expressed feeling revived by the opportunity to share their story.”

Perception gaps

Despite common “culture war” narratives that pit LGBTQ and religious groups against one another, these communities frequently intersect.

“[Queer people] are religious,” says Rachel M. Schmitz, an Oklahoma State University professor who researches LGBTQ resistance and resilience. “People’s experiences in that overlap tend to get overlooked because we just want this easier, neater explanation.”

Simply chronicling people’s experiences can be powerful. In various studies, participants “all say that it’s affirming to be listened to, to get their voices out and maybe help somebody else down the road,” says Dr. Schmitz. “It’s like a form of advocacy and giving back.”

There are also far more churchgoing allies of LGBTQ congregants than people believe, says Victoria Kirby York, deputy executive director of the National Black Justice Coalition, who uses she and they pronouns.

In her two decades of organizing, Mrs. Kirby York often worked with pastors who personally supported LGBTQ rights but wouldn’t take a public stance for fear of splitting their congregation. Meanwhile, studies by the Public Religion Research Institute have shown that a strong majority of people in nearly all major religious denominations support same-sex marriage or laws protecting LGBTQ people from discrimination. Among Black Protestants, 86% now support anti-discrimination laws, up from 64% in 2015.

“People of faith who are affirming of LGBTQ people were not as loud as our opposition,” she says. “We’re sitting in pews at church, essentially thinking everyone around us are homophobic and transphobic. … And turns out 7 out of the 10 people in the pew are right along with you.”

If that kind of support existed in Mr. Abram’s childhood church, he couldn’t see it.

Growing up in South Side Chicago, he faithfully served as a junior deacon, usher, and choir member at the Greater New Mount Eagle Missionary Baptist Church before he began preaching at age 14. By 17, his rousing sermons landed him on the front page of the Chicago Tribune.

Mr. Abram felt celebrated, beloved, and afraid. The local phenom worried he’d lose everything if the pastor discovered he liked boys more than girls, so he kept that part of himself a secret for years.

It wasn’t until he entered Harvard Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that Mr. Abram came to embrace his full identity as a self-described “queer church boy.” This is also where he met part-time student Karl Bandtel, whose philanthropic foundation would later provide seed money for the Pride in the Pews project.

The power of storytelling

In the year since starting Pride in the Pews, Mr. Abram has interviewed people from across the country, ages 22 to 85, each with a unique relationship with the Black church. Driven by a deep love for both the Gospel and the Black church’s legacy of social justice, Mr. Abram aims to mine their stories for insights that can help congregations become more welcoming toward LGBTQ members.

Among the early participants – found mainly through social media ads and word of mouth – was Ms. Crank; her fiancée, Kambriana Gates; and Jonathan Allsop, a first-generation American who grew up a Seventh-day Adventist.

To Mr. Allsop, the Black church is about a unique culture of worship. “There’s this unspoken rule that you are allowed to be free and vocal in your spirituality,” says Mr. Allsop, who no longer attends church regularly. “When someone is singing, you can stand up and engage yourself in a way that I don’t see in a lot of other churches.”

After coming out, he tried attending multicultural churches that were LGBTQ-affirming. But none came close to this worship style, and in Mr. Allsop’s view, they failed to address issues of racism head-on. Yet the Black church’s focus on racism was also a source of frustration when he faced homophobia from church members.

“You don’t want to take the time to understand me, but you want people to take time to understand you,” he says. “That [hypocrisy] makes it very difficult for me to not be angry. And I think one day, maybe after I’m 30 and I’m a little more settled in life, I’ll be able to take that anger into something more constructive. But for right now, it’s really just a lot of anger.”

Over the holidays, Pride in the Pews reached its initial goal of 66 interviews – chosen for the 66 books in the Bible – with no plans of stopping. The group has also secured $50,000 from the Gill Foundation to continue its work, and Mr. Abram hopes to use some of that money to partner with the African Methodist Episcopal Church’s sexual ethics discernment committee, which has been tasked in part with hearing testimonies from LGBTQ church members.

The project isn’t really about changing people’s minds, he says. “It is simply an invitation to be in conversation. And I just believe that if they’re willing to hear, there’s no way they won’t be transformed by the stories of Black queer and trans folks.”

That transformation works both ways. Ms. Crank says her interview with Mr. Abram compelled her to officially enroll in Emory University’s divinity program.

“I was very afraid that I was going to get a ‘no’,” Ms. Crank says about the application process, “because I was so accustomed to ‘no’ to being who you are.”

Many of the schools that initially interested Ms. Crank had social contracts that her relationship automatically violated, and several church leaders declined to write her a recommendation letter for the Emory program. She sought advice from the school’s dean of admissions, explaining her struggle with building church relationships as an openly gay woman. They allowed her best friend from undergrad to write the letter, and shortly after, Ms. Crank was accepted with a three-year scholarship.

The news moved her to tears, she says. “That was the first time I was truly honest with anybody about where I was in this journey [of reconciling my LGBTQ and Christian identities], and they just accepted me with open arms.”

A complicated journey

At age 14, right as Ms. Crank was noticing her attractions to women, she and her mom switched to an overtly anti-LGBTQ Pentecostal church in Detroit. At 15, she started tarrying. While other teens struggled to receive the gift of tongues, Ms. Crank felt the Holy Ghost coursing through her and says she could “shanana” with the best of them. By 17, she found herself immersed in a double life, attending church several times a week and publicly dating boys, all while texting girls on the side.

These worlds collided when she was 19. During an annual youth retreat, the pastor looked out at the crowd and announced that someone in the room was a lesbian, and they were going to pray the gay out of them. Ms. Crank felt a sudden rush of shame. This is it, she thought, they know.

She stepped down to receive the prayer. The crowd laid their hands on her, dancing and shouting as Ms. Crank sat quietly on the steps.

She didn’t feel the Holy Ghost that day.

The moment triggered a pendulum effect in Ms. Crank’s life, with the young college student swinging from one extreme to another. First, she quit church and embraced what she describes as “a toxic form of masculinity,” dating several women and partying constantly. Within a year, she was getting baptized, leading Bible study, and trying to “act straight.”

After graduating, she met Ms. Gates, and that pendulum began to steady. The women bonded over Bible verses and discussions about faith, and as their feelings for one another grew, Ms. Crank was forced to reconcile her Christian and LGBTQ identities. In 2018, she wanted to leave the church, but through prayer and intense conversations with Ms. Gates, she chose to stay.

Now, they’re navigating the next chapter of the journey together – being an openly queer couple in the Black church. Their goal of finding a welcoming congregation where they’re allowed to serve is proving a challenge.

“When I decided to come back into the church, I was excited to just be at one church, serving,” says Ms. Crank, who loves engaging with ministry. “We will listen to this sermon and listen to these songs and let it hit our soul for our personal relationships with God. But I still think community is so important and it is missing in our life right now.”

Whenever she feels the weight of school, family rejection, or that familiar sting of “church hurt,” she considers how life might’ve been different if she saw someone like herself in the pews. Many young LGBTQ people are at higher risk of suicide than their peers, Ms. Crank points out.

“There are literally people dying feeling as if God does not love them. And I really want to change that,” she says. “My voice is important. Kam’s voice is important. Our voices matter.”

On Broadway: This musician is in the pits, but far from blue

The music industry can be fickle: One day you’re touring with Sting, the next you’re playing weddings. The key to perseverance, says one musician, is humility and finding satisfaction outside of ego.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Over the past 25 years, Jeffrey Lee Campbell has been an in-demand guitarist for Broadway musicals.

But when the pandemic shut down the Great White Way, he had the humbling experience of being unemployed for a year and a half. Many people in his industry abandoned the city. To lift his spirits, Mr. Campbell adopted the routine of a daily walk.

The guitar player recently invited the Monitor to join him for a trek of New York’s musical landmarks, including those in his own storied career. In a four-hour conversation spanning more than 45 blocks, the guitarist offered insights into the lives of musicians who toil in “the pit” beneath the stage. Longevity in the competitive profession requires qualities that helped him weather the pandemic: periodic reinvention, flexibility, and a willingness to check one’s ego at the stage door.

He has been buoyed by the songs he plays in a new show, “MJ.” Once music became a vocation, Mr. Campbell lost some of the innocent joy he first felt as a budding guitarist. Michael Jackson’s catalog has revived it.

“When I start playing that opening guitar lick on ‘I Want You Back,’ I’m 10 years old again,” he says.

On Broadway: This musician is in the pits, but far from blue

On one of his daily walks across Manhattan, Jeffrey Lee Campbell pauses in front of the Gershwin Theatre on West 51st Street. Standing beneath the theater’s signs for the musical “Wicked,” he peers into the lobby. Decades ago, he worked the concession stand here alongside a young Aaron Sorkin, the now-famous writer and director.

“See that black door there, the checkroom? I was standing in that room in 1987 when Prince walked through here,” marvels Mr. Campbell. “When I walk to these places that are still standing, I try to look for ‘1987 Jeff’ standing in that door to remind me to stay humble.”

Over the past 25 years, Mr. Campbell has been an in-demand guitarist for Broadway musicals. But when the pandemic shut down the Great White Way, he had the humbling experience of being unemployed for a year and a half. Many people in his industry abandoned the city. To lift his spirits, Mr. Campbell adopted the routine of a daily walk.

The guitar player recently invited the Monitor to join him for a trek of New York’s musical landmarks, including those in his own storied career. In a four-hour conversation spanning more than 45 blocks, the guitarist offered insights into the lives of musicians who toil in “the pit” beneath the stage. Longevity in the competitive profession requires qualities that helped him weather the pandemic: periodic reinvention, flexibility, and a willingness to check one’s ego at the stage door. They’re innate to Mr. Campbell, says saxophonist Branford Marsalis, who has known Mr. Campbell for three decades.

“The Broadway of now is not the Broadway of my childhood,” says Mr. Marsalis. “It’s a lot of pop music and folk music. ... You have to be able to play a lot of different styles. And you have to play in a way that you understand that there are singers and talkers and dancers onstage. It’s such a perfect thing for Jeffrey.”

Mr. Campbell begins his walking journey near Times Square and heads uptown. His pace, a lingering vestige of his North Carolina upbringing, is as leisurely as the ascent of the December sun overhead. As the guitarist passes billboards for “The Music Man” and “Caroline, or Change,” he admits he had zero interest in musical theater when he moved to New York.

When he arrives at 1776 Broadway, he proclaims, “This is the building that changed my life.” It was here that he first met the manager for Sting. Mr. Campbell successfully auditioned to become the guitar player for the rock star’s 1987-88 tour – a feat for a newcomer. Sting told him, “I’m going to make you famous.”

Mr. Campbell toured the world in private jets, played a spotlight solo on “Saturday Night Live,” and hung out with the likes of Eric Clapton and Bruce Springsteen. But afterward, Sting hired an entirely new band for the next album and tour. Mr. Campbell went from playing Madison Square Garden to performing in a wedding band on weekends.

“I thought I had cracked the code of showbiz,” says the musician. “As I joke to people, ‘I spent the next 35 years working my way down the ladder of success.’”

Resuming his walk, the musician tells the story about his next big break. A decade later, on the recommendation of a friend, he got added to a list of substitute musicians for Broadway shows.

“I’ve had guys call me at quarter to 8 and say, ‘Can you play the show tonight?’” he recalls. “I’d take my food out of the oven and put on my clothes, and I’m there 10 minutes later, ready to play.”

It’s a difficult circuit to break into. Staying on the list of approved subs means you have to impress conductors in the orchestra pits. Mr. Campbell prepared with the same fastidious attention to detail that he’d applied to the Sting audition.

“He wasn’t a flashy instrumentalist, but he was a musician,” recalls Mr. Marsalis, who was on the same tour with Sting. “He knew how to play guitar to accompany the band and to support Sting’s music, which means that you’re essentially invisible. If you’re doing your job well, no one notices you.”

Being comfortable with anonymity is requisite for Broadway musicians. They play unseen in an orchestra pit. After several years of subbing, Mr. Campbell landed his first full-time gig on “Saturday Night Fever.” His subsequent credits include “Seussical” and “School of Rock.” He played on “Mamma Mia!” for 14 years. Mr. Campbell’s philosophy, as noted in one of his books, is “Stay positive. You’re always exactly where you’re supposed to be.”

Strolling through Central Park, where our noses perk up at the aroma of a street vendor’s roasted peanuts, Mr. Campbell says that playing shows – eight per week across six days – is a meditative experience. He’s so attuned to his musical cues that he can read a book between songs. But he challenges himself to play better each performance.

“I have friends who would not want to play the same music night after night, but as my fellow guitarist in ‘Mamma Mia!’ said, ‘Go on the road with Lady Gaga and let me know how much the music changes every night,’” he says.

In March 2020, after just his third performance in “Mrs. Doubtfire,” Broadway shuttered. During the seemingly endless hiatus, he revisited an avenue of creativity that he’s found invigorating and rewarding: writing. He’s almost finished a memoir titled “The Fuzz Box Diaries.” It’s a follow-up to his 2018 book, “Do Stand So Close: My Improbable Adventure as Sting’s Guitarist.” The books are a result of him contemplating his legacy. “I would trade every note I’ve ever played to say I wrote ‘Crazy’ by Willie Nelson or ‘Every Breath You Take’ by Sting,” says Mr. Campbell. “My fantasy was always to hear a car going on the street blasting a song I’d written.”

But he’s arrived at a feeling of gratitude for achieving a career in music.

“You can be on the New York Yankees and still not be Mickey Mantle,” he says. “The hardest threshold to cross is being a full-time musician, to not have a day job. Most people end up still having to work somewhere else and they play music for fun.”

The guitarist’s circuitous walk ends outside the Neil Simon Theatre on 52nd Street. The marquee features a silhouette image of Michael Jackson for the musical “MJ.” It’s a brand-new show, slated to officially open Feb. 1. Mr. Campbell is its rhythm guitarist.

Two days earlier, on his way to the musical’s first preview performance, Mr. Campbell wondered why there was a line of people around the block. It dawned on him that they’d come to see “MJ.” During the standing ovations, the catharsis was similar to when “Mamma Mia!” resumed days after the attacks of Sept. 11. Maybe more so, he says.

His emotions have also been heightened by this show’s material. Once music became a vocation, he’d lost some of the innocent joy he first felt as a budding guitarist. Michael Jackson’s catalog has revived it.

“When I start playing that opening guitar lick on ‘I Want You Back,’ I’m 10 years old again,” says Mr. Campbell. “And the intention and the passion that I play it [with], and the memories that come flooding back to me from playing those songs, it’s just overwhelming.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

New voting districts, the citizens’ way

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For more than a few years, democracy watchdogs have expressed concern about the United States. The Economist Intelligence Unit, for instance, ranks the U.S. as a “flawed democracy.” Yet this concern misses a significant measure of civic renewal on another key aspect: the task of defining the community of voters who elect each legislator.

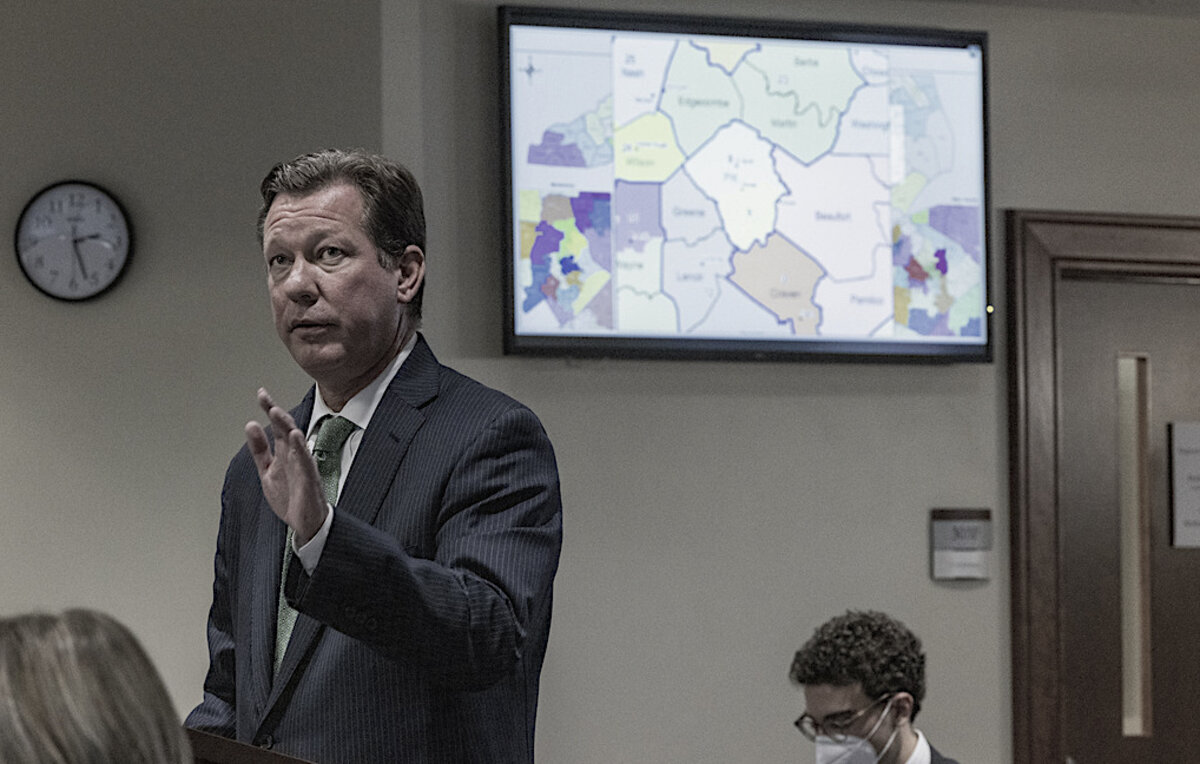

As states finish up redrawing maps for new voting districts based on the latest census data, American democracy is functioning robustly in exactly the way it was designed to do. Citizens are engaging in the once-opaque process with unprecedented intensity. Courts are rejecting grossly partisan maps. Politicians, voters, and judges are engaged in vigorous debates about what fairness means. In 2000, congressional districts were redrawn by legislators in 27 states. This year, that number has dropped to 20.

As states redraw their districts in time for the coming primary elections, the ongoing challenges show that attempts by one party or the other to lock in unfair advantages have not ended. But democracy is finding renewal in scores of citizen-led efforts to participate in how elections are shaped and fairness is defined.

New voting districts, the citizens’ way

For more than a few years, democracy watchdogs have expressed concern about the United States. The Economist Intelligence Unit, for instance, ranks the U.S. as a “flawed democracy.” Much of the concern is over the fairness of the voting process itself, such as access to voting and who verifies ballot counts.

Yet this focus misses a significant measure of civic renewal on another key aspect: the task of defining the community of voters who elect each legislator. As states finish up redrawing maps for new voting districts based on the latest census data, American democracy is functioning robustly in exactly the way it was designed to do.

Citizens are engaging in the once-opaque process with unprecedented intensity. Courts are rejecting grossly partisan maps. Politicians, voters, and judges are engaged in vigorous debates about what fairness means.

“We’re back to the principle of people should pick their politicians, rather than the politicians picking their people,” Jack Young, a redistricting committee co-chair of the League of Women Voters in Delaware, told the Delaware State News.

Redistricting bundles voters and communities together for elections based on new population data every decade. For most of America’s history, the process was carried out almost exclusively by state and local politicians and subject to a highly partisan process known as gerrymandering. The party in the majority drew new maps based on voting records to lock in an advantage at the ballot box.

Over a couple of decades, many citizens have been trying to pry the process out of the legislators’ hands. This year they may finally be getting some leverage. In 2000, according to data compiled by Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, congressional districts were redrawn by legislators in 27 states. This year, that number has dropped to 20. The change reflects a shift in favor of independent commissions, courts, and citizen oversight.

In 2018, Ohio voters approved a constitutional amendment creating a minimum threshold for bipartisan support of new district maps. For the second time, the Supreme Court of Ohio rejected a map this month proposed by the legislature for failing to meet the new requirement. Across the country, scores of old and new civil society groups are forcing reviews of maps down to the county level that carve up communities into multiple districts.

At the local level, for example, city officials in Hendersonville, Tennessee, adopted a redistricting plan drawn by a citizen committee rather than their own. The plan will require three current aldermen to face new constituencies if they decide to seek reelection. The city plan would have preserved their districts.

That pushback reflects a deeper search for how to ensure that each person’s vote is equally valued. Defending such equality in the democratic process, says U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock of Georgia in a recent interview with NPR, is “really about the dignity of everybody’s humanity and our ability to build a future that embraces all of us.”

As states redraw their districts in time for the coming primary elections, the ongoing challenges show that attempts by one party or the other to lock in unfair advantages have not ended. But democracy is finding renewal in scores of citizen-led efforts to participate in how elections are shaped and fairness is defined.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

From soul to Soul

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Nathan Talbot

The traditional concept of “soul” is that it is contained within the body. Our thoughts and lives are immeasurably blessed by a deeper understanding of Soul as infinite, never within matter.

From soul to Soul

While flipping through some TV channels in search of a particular news program, I paused when hearing the word “soul” spoken in a dialogue between a talk show host and her guest. I believe the guest was commenting on a more traditional view of soul in the body and the host said something like, “But I think soul is everywhere.”

Although the conversation was some years ago, the idea of Soul being everywhere was the impression I was left thinking about. And it has stuck with me.

The concept of Soul had always been a little obscure for me until a summer break in my college years, when I took a two-week course known as Primary class instruction in Christian Science. I came away inspired about a lot of things, but perhaps nothing was more enlightening than a far more expansive view of Soul.

The teacher in the class explained that Christian Science uses the term “Soul” as a synonym for God, and that all God’s children are actually spiritual, not material. They are in reality made in the very image and likeness of the one perfect Soul who is God. As the discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, writes, “Science reveals Spirit, Soul, as not in the body, and God as not in man but as reflected by man” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 467).

For me, this sense of Soul with a capital S has increasingly come to mean the pure and sinless nature of God. From divine Soul comes joy, innocence, and peace; harmony, health, and spiritual poise; and many other qualities.

Understanding this has a very practical impact. Learning that Soul is God, everywhere, instead of contained within a body of matter, and that as God’s expression, we manifest the qualities of Soul, has nurtured a freedom that has significantly empowered me in many ways. It has enabled me to demonstrate harmony when conflict tried to arise, moral strength when sin offered temptation, peace when doubts were felt, and health when I was sick.

The more we learn about Soul as God, and all individuals as beautiful expressions of Soul, the more spiritually strengthened we will be by this simple but expansive view. Understanding that we are planted firmly within infinite Soul brings a genuine stabilization to our lives. God gives us this assurance in the Bible: “Yea, I will rejoice over them to do them good, and I will plant them in this land assuredly with my whole heart and with my whole soul” (Jeremiah 32:41).

Just as astronomy helps us see that instead of the sun rising, the Earth turns, so divine Science gives us a fresh view of Soul as not contained in, but expressed by, every individual’s true God-given nature. And this inspired conviction that Soul is not limited within us, but is manifested by us, brings amazing blessings to our lives.

A message of love

Tracks of remembrance

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when our Chelsea Sheasley looks at an effort in Tennessee to get past the hard lines on the issue of teaching race in schools to a more meaningful dialogue.